The following is excerpted by Phaidon's newest release, Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing.

Vitamin D2 is available on Artspace for $39.

Vitamin D2 is available on Artspace for $39.

Photorealism, often referred to as Superrealism or Hyperrealism, describes a movement of painters whose work was characterized by precise detail, advanced technical skill, and a deceptive quality of image. Using processes such as airbrushing, projected photographs, and gridded canvases, Photorealist painters often depicted objects, landscapes and portraits with reflective surfaces, adding to the three dimensional nature of their compositions. Heavily reliant on photography, the beginnings of Photorealism can be traced to mid-1960s New York, following in the footsteps of Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism. By the time the style picked up in the 1970s, many established artists were working in this photo-based movement, including Chuck Close, Don Eddy, Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Robert Bechtle, Audrey Flack, Denis Peterson, and Malcolm Morley.

The following seven contemporary artists, taken from Phaidon's newest release, Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing use the illusionistic methods, and sublime detail of photorealism, though each to every different ends.

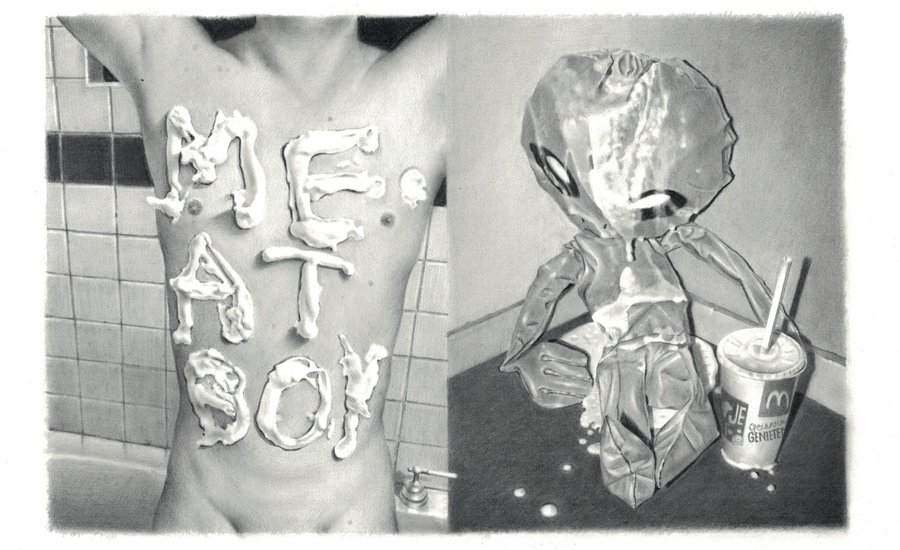

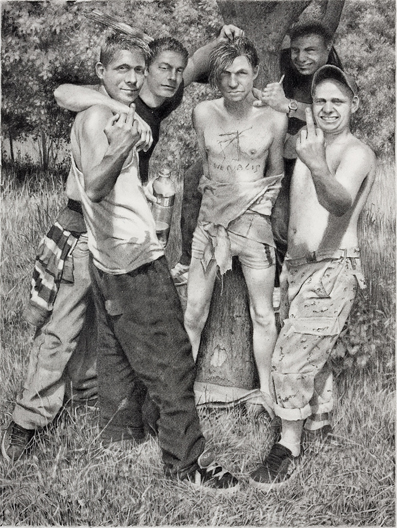

DAVID HAINES

No Nacis, 2011

Pencil on paper

An investigation into the dialectical structures of mythology underpins the meticulous, hyper-real drawings of Amsterdam-based artist David Haines. Claude Lévi-Strauss understood mythological thought to be that which "always progresses from the awareness of oppositions towards their resolution." That is to say, myths comprise contradictory elements as well as those serving to mediate or resolve those oppositions. With an exquisite technique, Haines embeds these ideas in his works, which are at once seductive and disconcerting. Take Adidas Chicken Convection (2010) for example, in which two youths crouch beneath a dingy concrete flyover. One devours a fast-food meal, while the other, his face half concealed by a Burberry scarf, casts an intimidating scowl as he attempts to cook a chicken with a cigarette lighter. As Lévi-Strauss asserted, the opposition between raw and cooked food, elaborated in myths and rituals around the world, expresses the universal distinction between nature and culture. Such collisions of ancient thought and contemporary experience typify Haines’s recent works, serving to affirm the universal language of myth famously espoused by the French anthropologist.

Haines, however, resists any attempt to update the myths of the past, finding instead contemporary expressions of the underlying dialectics that shaped the surreal and frequently gruesome tales of the ancients. Much of his imagery originates online, taken from obscure fetish websites and other shadowy corners of the internet. In this way he creates contemporary myths for the digital age.

Haines’s drawings display an unfettered fascination with what the British commonly refer to as "scallies" or "chavs"—working-class adolescents with a penchant for branded designer sportswear and gold jewellery. As may be witnessed in virtually any UK town centre, Burberry caps, hooded tops and Adidas trainers are common attire among this British subculture. Classic brands such as Osiris, Reebok and Nike are also popular and appear as leitmotifs throughout Haines’s work, alluding to the way in which key elements are often repeated again and again in mythological thought. Not only do the names project a disarming familiarity, but they also carry strong mythological resonances that introduce subtle subtexts into the work. For instance, the African species of antelope known as rhebok, from which the popular sportswear brand derives its name, becomes excessively aggressive during the breeding season. Aggression and violence, both overt and covert, are recurring themes for Haines, yet the true nature of these images often remains ambiguous. For instance, are the violent scenes depicted in Baroque Semiotics (2012) and No Nacis (2011) acts of sadistic bullying or perhaps some kind of mysterious initiation ceremony? Whatever the answer, they, as with the rest of this artist’s oeuvre, make for uncomfortable yet utterly compelling viewing. - David Trigg

MARIA KONTIS

Argument for a Stationary Earth, 2012

Pastel on velvet paper

From Eugene Atget to Tacita Dean, the outmoded object has been a central concern for artists wishing to explore the affective potential of the discards of modernity: the disappearing traces of nineteenth-century Parisian architecture or the abandoned snapshot appear in such artists’ works as a means to return the forgotten past to the present. The outmoded object also forms the basis of Maria Kontis’ drawing practice. Working with found photographs and materials, as well as her own photographs sourced from her personal albums, Kontis’ drawings bring to the fore an often elusive past for the viewer’s contemplation.

The affects of Kontis’ drawings—nostalgia, mourning and loss in particular—have much to do with her emulation of the aesthetics of the faded black and white analogue snapshot. Working with pastel—for example in Argument for a Stationary Earth (2012)—she produces monochrome drawings that appear to be truthful and skillfully copied renditions of photographs. However, this aesthetic affect is an illusion. For any single image, she edits, crops and erases particular details of her myriad image-sources. "Sometimes," states Kontis, "the drawing is very close to the original photograph and sometimes it doesn’t resemble it at all, but it still looks like a copy of a snapshot." Her ability to produce a convincing reproduction of an outmoded black and white photo via drawing is crucial for understanding her work’s ability to generate an aesthetic of nostalgia.

The relations between nostalgia and the photographic image are well known. But the digital era introduces a range of technological and cultural shifts with regard to our understanding of the photographic image and the past. Today, the photograph is not so much a means for preserving a frozen moment in time for posterity, as a catalyst for constant and instantaneous reporting and sharing on the internet; it is not a material object bound to and protected by the family album, but a series of pixels on a screen – an immaterial product that is part of an increasingly expanding and amnesiac digital culture. Kontis’ simulations of monochrome snapshots—which most often recall earlier decades of the twentieth century— invoke a slower and more intimate relationship to the photographic image than that which is common in the digital era. - Veronica Tello

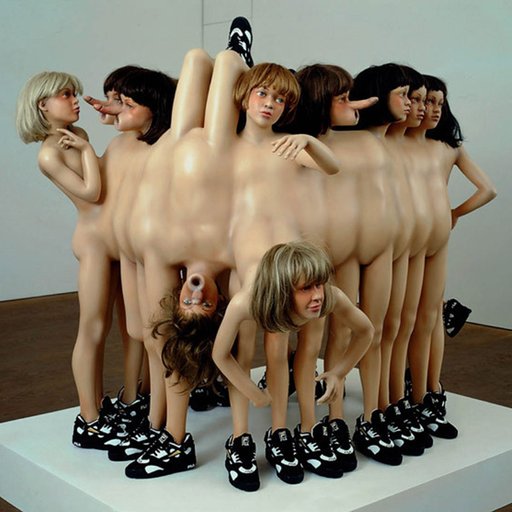

JOSE LEGASPI

Untitled, 2011

Pastel on paper

Perhaps in no other artist’s work do the eyes stare out more aggressively than in those of Jose Legaspi. In his large recent drawings, the figures are impeccably and hyper-realistically made in pastel. The smaller drawings are done in charcoal and everything about them is quicker, rougher and more in flux. It seems as if he is making a divide between public and private, or else between the cultured and the irrational. In the larger works, figures are isolated, sometimes striking a pose or holding some fetishistic or threatening object. The figures in the small works seem drawn with the rage and obsessiveness of a psychotic.

If the larger figures are isolated like people frozen in a searchlight, in the smaller drawings they are subjected to extreme violence. Sometimes, the eyes are torn out. In a series of drawings entitled Bakla, Christ on the cross and a woman (the Madonna?) have only bloody sockets for eyes—they cannot see what is happening elsewhere. Bakla is a word that periodically appears in Legaspi’s drawings and is a pejorative term for "gay".

It is tempting to see Legaspi’s practice in the light of the Catholicism that dominates cultural and social life in the Philippines. Legaspi has never hidden his sexual orientation or how that has conflicted with a traditional upbringing in this profoundly Catholic country, where it is possible to see the ostracism of a gay man as being akin to that of the early Christian martyrs. Blasphemy still has a power there that it has partially lost elsewhere—an early exhibition of Legaspi’s which included a sculpture of the Virgin vomiting on the baby Jesus created a scandal.

The intensity of his work is accentuated by the way in which he creates installations using many drawings, whereby there is great tension between the large pastel and the smaller charcoal drawings. The repetition of images of horrors, empty rooms and alleys and flying figures has a cumulative effect on the viewer. Even in a commercial gallery, his small drawings are exhibited and sold as sets to ensure they are considered parts of a larger whole. The work is clearly confessional—the model for the large drawings is often himself—but is also fantastical. What may not initially be apparent is that mixed in with the horrors are images of release: flying, flowers, light. Where his work is in fact most Catholic is in this sense of possible redemption, even if the route to it is personal and often painful. The persistent emphasis on eyes, staring or bleeding, should awaken us to a perhaps even deeper subject: the act of looking, which in a desiring relationship between two people becomes physical touch. These are drawings about being alone but longing not to be. This is drawing that yearns for company. - Tony Godfrey

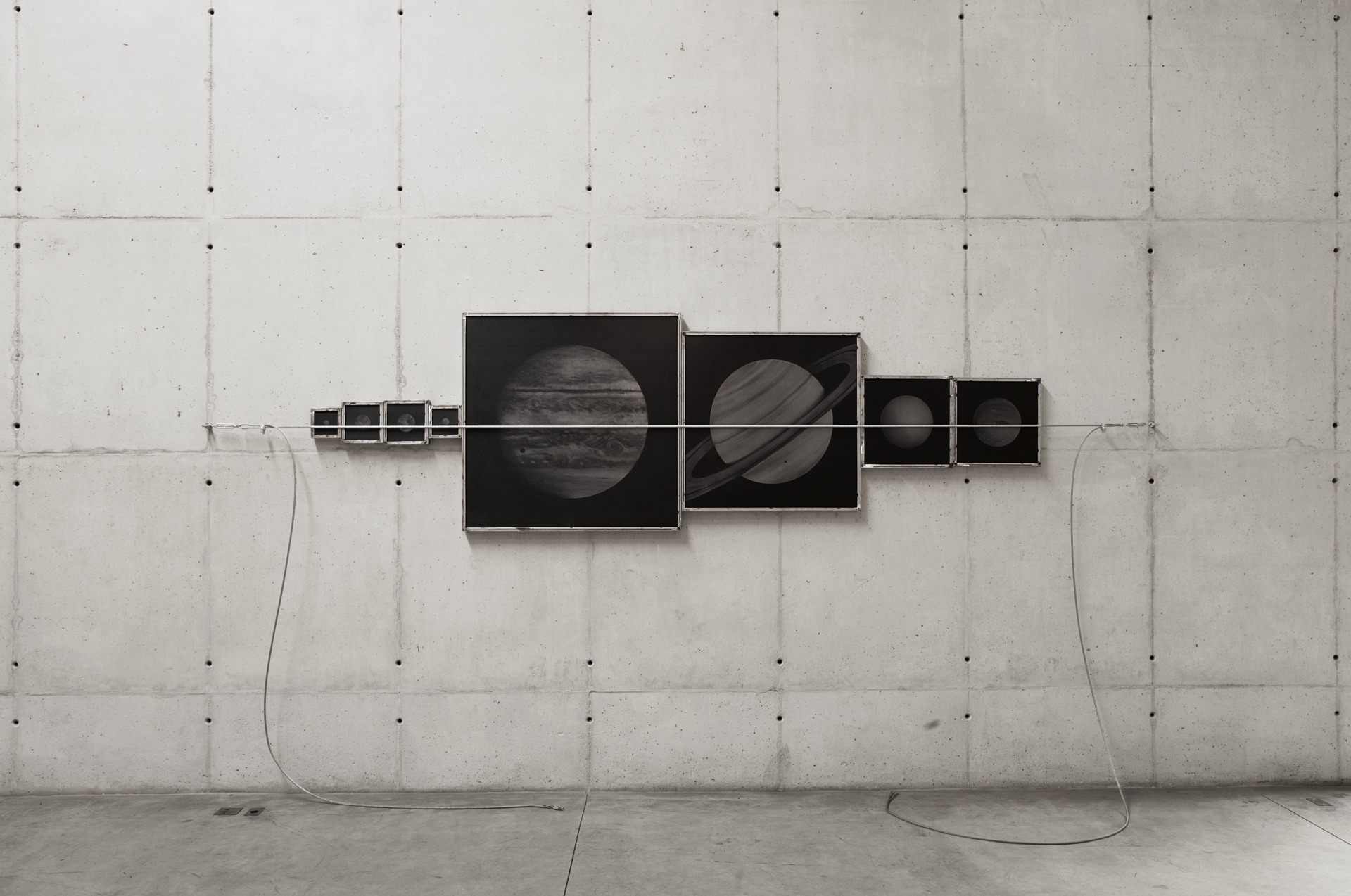

MARCELO MOSCHETA

Atlas, 2011

Graphite on PVC board, iron, and steel cable

Beginning with the Situationists, walking has become a way of disengaging from the passive attitude imposed by the society of spectacle, whereas counting, measuring and archiving (steps, found stones, units of distance travelled), and perhaps collecting something along the way, are gestures that save the action from oblivion and immortalize it, inevitably transforming it into something else.

Some of Marcelo Moscheta’s works are part of this lineage: his Stones Series (2009), for example, comprises a number of stones collected while walking over several days, and each is identified with the exact coordinates of the site where it was found. There are analogies between this work and some of Richard Long’s actions or, more recently, Helen Mirra’s, but what makes the Stones Series unique is the "portrait" that comes with every stone, executed with extraordinary virtuosity by the artist in graphite on PVC board. In the drawing, he uses a highly original technique: starting from a photo - graph, he creates a "mask" by scoring a sheet of tracing paper with the exact outline of the stone. Then he cuts it out and covers it with graphite powder, and finally rubs it off with an eraser to bring out the shape. This method might be viewed as closer to sculpture than drawing, at least from the angle of Michelangelo’s celebrated definition of sculpture as what is done per forza di levare (by taking away).

This is significant, considering that most of Moscheta’s recent works, even those in which drawing is central, are eminently sculptural and installation-like. In 33 Mountains (2010), for example, drawings are mounted on long iron "legs", while in Atlas (2011) images of each planet in the solar system are held against the wall by a steel cable. In both works it should be noted, drawing is still used as a measurement system. In the first case, the number of mountains alludes to the age of the artist himself when the work was done, while in the second, the size of each planet is correctly proportioned in relation to the Earth. Alluding respectively to the implications of a symbolically charged age, and to the Titan in Greek mythology who carried the world on his back, these works also point to the spiritual, almost mystical dimension of Moscheta’s landscapes.

It is in the clash between the desire for accurate measurement and the fascination with the unfathomable immensity of the world that the core of his work resides. In this sense, the work is part of the great Romantic tradition of confronting humanity with the vastness of nature. Fascinated by heroic scientific expeditions of the past, the artist set up residencies in remote places such as the Arctic Circle or the Atacama Desert in Chile, where he produced works in which the relationship between Man and Nature becomes central, although elliptically so. In other words, and surprisingly considering the frequent absence of the human figure from these images, the authentic protagonist of these works is the man—a small figure in contrast to the vastness of the horizon—who walks, measures, observes and notes. - Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

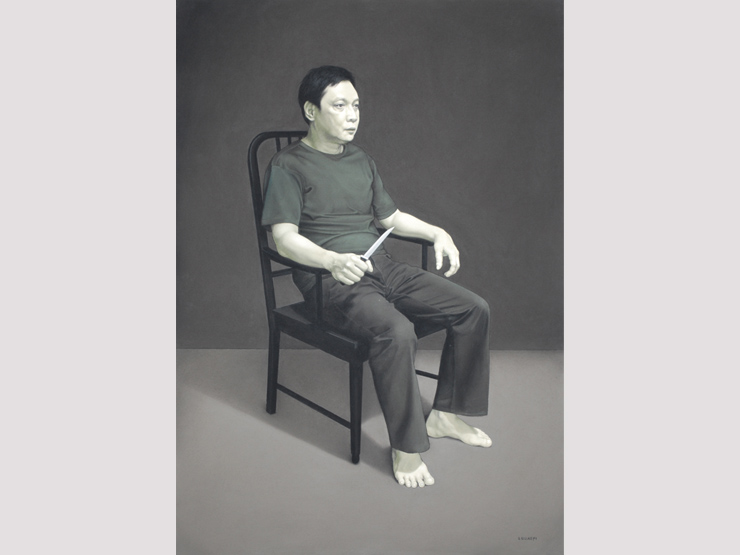

J. ARIADHITYA PRAMUHENDRA

The Reunion (Ashes to Ashes), 2010

Charcoal on canvas

Enigmatic, evocative and poetic, J. Ariadhitya Pramuhendra’s works have a distinctive black and white mise-en-scène. Both in his drawings and installations, he continually experiments with scenography, in which figures’ gestures, facial expressions, costumes and contexts are carefully arranged to elicit his intended meanings. Trained as a printmaker, he now primarily uses dry media such as pencil and charcoal on paper or canvas to create images laden with intense, meticulous and rich greyscale. Even when he works with photography, he tends to maintain his insistence on black and white. Across his chosen media the detailed chiaroscuro effect and scenography combine to create dramatic visual impact.

From his sensitive exploration of chiaroscuro, Pramuhendra has learned to use greyscale as a metaphor. This is particularly obvious in his work A Heaven’s Tale (2010), in which he presents light to suggest the presence of the Divine. The dramatization underlines the meandering spiritual path that he has been taking, suggesting that his art practice is a process that leads him into the most subjective as well as contemplative stages of understanding religion.

The artist’s long use of charcoal has brought him to another understanding of the material. He juxtaposed one of his large drawings, The Reunion (Ashes to Ashes) (2010), with an installation of a burnt clock and table, charcoal and ashes. The black tones of the objects and the clean white space around them created a dialogue with the drawing, making a coherent installation unified by charcoal and the remnants of death. The presence of charcoal and ashes in the installation goes beyond mere physical death, however: the artist also connects it with the ritual of Ash Wednesday, which in Catholicism represents the idea of human mortality. Since this exhibition, charcoal has become for the artist both a medium and a symbol of the immaterial.

Indeed, Pramuhendra is a devout Catholic; born into a Catholic family in Semarang—a provincial capital in the northern coast of Java island—he embraced religion as a guiding force in his life. While following the holy teachings, he is also aware that religious life in Indonesia has been born out of a syncretic encounter with native cultures, as well as with other religions. It is the specific cultural life in Indonesia—a multi-ethnic and multi-faith society—that gives Pramuhendra his personal drive to explore religious icons, symbols and rituals, with the intention not only of expressing his religious adherence, but also his cultural observation of it. For him, symbols and rituals are forms of language that must be digested on a personal level; yet they must also be freely and critically interpreted in order to understand the society in which they function. - Agung Hujatnikajennong

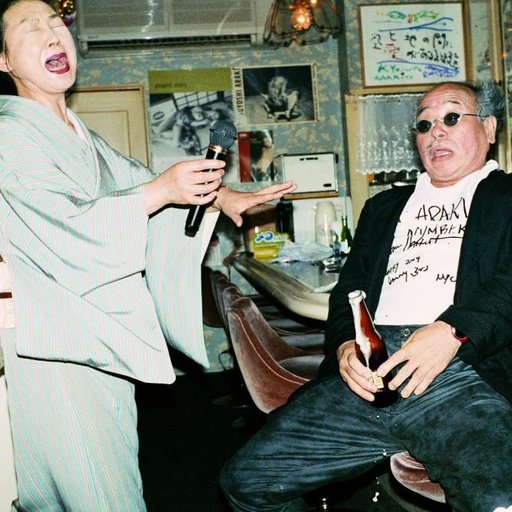

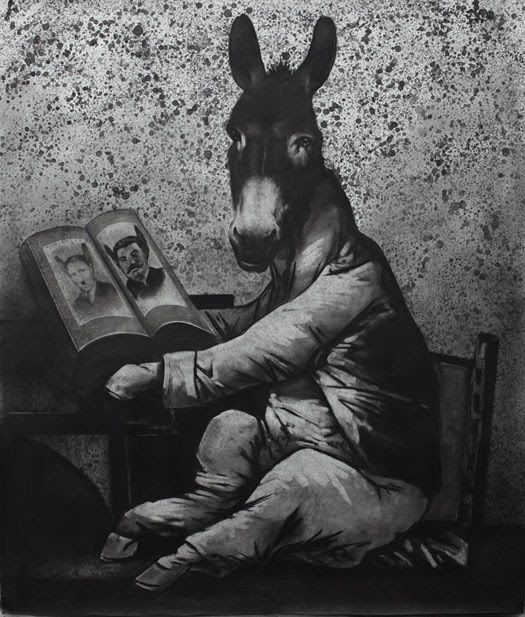

MIRCEA SUCIU

Hasta Su Abuelo (And so was his grandfather), 2012

Charcoal on paper

Mircea Suciu is one of Romania’s leading artists. Part of the so-called Cluj School—the internationally regarded current generation of artists from the capital of the province of Transylvania—he has a studio in the city’s Fabrica de Pensule, a converted paintbrush factory that with its galleries, artists’ studios, design and performance spaces, has become the centre of Cluj’s cultural activity.

Suciu trained in the painting department of Cluj’s University of Art and Design alongside Marius Bercea, Adrian Ghenie, Serban Savu and Victor Man. His paintings came to international attention in 2008 when his work was featured on the cover of the October issue of ARTnews. The following year he participated in the Istanbul and Prague Biennials. More recently his paintings have been included in the 2012 exhibition of Cluj artists at the Mucsarnok Kunsthalle, Budapest, "European Travellers". However, "Black Milk", his 2012 solo exhibition at Aeroplastics Gallery, Brussels, marked a bold transition in his practice from painting to charcoal drawing. The title of the exhibition was derived from Paul Celan’s poem, "Death Fugue", published in 1948 and considered one of the great works written by a Holocaust survivor. The poem, which features the words "black milk" as part of a recurrent refrain, describes how prisoners are forced to dig graves while others play music.

It is a characteristically bleak point of departure for the artist. Taking his cue from Goya, who quipped: "Give me a charcoal and I’ll paint your portrait," Suciu has implemented a technique uniquely his own. Fascinated by what he describes as "the absurd actions of man", and repeatedly drawn to the mid-twentieth century for inspiration, he sought a medium that would enable him to capture one of the darkest times in history. Charcoal allows its user to be bold and expressive. In Suciu’s work we not only find line and tone but finger prints, brush work, rag marks and thinners mixed with macerated charcoal powder to create a suspension similar to pointillism. Suciu is a master of chiaroscuro, boldly contrasting bands of light or spot-lit bodies with looming shadows and unfathomable grounds. He describes this strangely heightened world as "psychological realism".

Finding imagery from the past through contemporary sources such as the internet, Suciu builds dramatic compositions that function on different levels. Sometimes they are deceptively simple, featuring a lone figure set against a flat background; at other times they are so intensively peopled that they become unreadable in a narrative sense and akin to abstraction.

Suciu watches people intently. The common man is caught mid-action, whether in despair, hedonism or willful ignorance. Yet though he may appear foolish, even pathetic, it is not the common man that Suciu satirizes, but those who exploit him, such as figures of state or religion. These are sometimes depicted as corruptive abusers, or derided as figures of fun; for though Suciu’s work is dark, it is also laced with humor and irony. His concern with social critique cuts him from the cloth of Bosch, Goya, Hokusai, Daumier, Redon, Lautrec, and Kentridge, but like those who have gone before him, his concern for humanity is balanced and at times even overtaken by his passion for his medium of choice. - Jane Neal

IRIS VAN DONGEN

Affair I, 2009

Soft pastel and charcoal on paper

In her haunting large-scale portraits of isolated, usually pensive women (and more recently, men), Iris van Dongen beautifully, and often eerily, balances the dynamic between classical and contemporary. She works primarily in pastels and charcoal—applying the medium to her fingers and then tapping it on to the paper in layers—rendering scenes that evoke fashion spreads from contemporary magazines, which she stages and photographs herself. However, she recreates these scenarios with a particular lens, placing less emphasis on the facial expression of the figure than on the interaction between the sitter and her environment. "I want the viewer to almost look past the person as if she were an abstract object," says van Dongen.

Born in the Netherlands and trained at the Academie voor Kunst en vormgeving’s-Hertogenbosch, van Dongen got an early start in printmaking. "From [the ages of] 18 to 23, I would mostly make etchings and stone lithographs. I love the subtleness the black ink gives to a print," she says. "I wanted to expand this technique in my own way, to make works bigger in scale and freer in material use, but still keeping the same appearance." She started by experimenting with abstract drawings before becoming confident enough to tackle photographic realism.

"As a kid I used to read my father’s books of Ed van der Elsken and Diane Arbus. [My father] was also a Klaus Kinski freak, so I saw Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) at the age of twelve," she says. Her drawings clearly reflect these influences, as well as the paintings of Dutch masters (notably Vermeer and van Eyck), etchings by Goya, and classical Italian portraits. The sober color palette of Dutch painting, the intimacy and intense emotion of pre-Raphaelite scenes, and a cinematic quality are married in these drawings of seductive or ethereal female figures.

Interested in the separation between the rational and irrational, the metaphysical and the subconscious, van Dongen explores subjects such as life, death, melancholy and passion in her work. In one series of paintings, she investigated hooliganism and fanaticism, linking collective contemporary and ancient symbols, like a football club logo and a black skull. "I just try to understand some things in life that I really don’t understand or that I dislike—the scary behavior of people," she says. "Therefore I integrate it into my drawings so it becomes a part of me, so I don’t have to be so afraid of life anymore." More recently, she explored the satanic "red eye" effect that flash cameras so often produce in photographs. "Red eyes are a thing you can only see in photos," says van Dongen. "I liked that fact, and used it in my work. So you could say my work incorporates new media in old techniques." - Marina Cashdan

RELATED COLLECTIONS:

Photorealism

RELATED ARTICLES:

7 Contemporary Drawings that Revitalize the Medium