Ilya Kabakov, born in 1933, spent thirty years in the USSR as an 'unofficial' artist before coming to western attention in the 1980s. He is now recognized as one of the most important Russian artists of the late twentieth century. Kabakov's satirical drawings, narratives, and all-encompassing installation spaces speak as much about conditions in post-Stalinist Russia as they do about a universal human condition.

Ilya and his wife Emilia have been collaborating on installation-based works since 1985. In their work, the duo builds structures teeming with metaphor, involving imaginary characters and narratives. The couple has a busy Fall: This month, a retrospective of their collaborative and solo work, "The Utopian Projects," opens at at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C. (on view until March 4, 2018). The show includes studio models, outdoor installations, and iconic works including The Man Who Flew Into Space From His Apartment , and The Ship of Tolerance , a sixty-foot wooden sailboat that has sailed around the world and is celebrated for its message of acceptance and hope. Next month, the Kabakov's will have a major exhibition at the Tate Modern, showing three rarely exhibited "total" installations presented together for the first time.

To prepare ourselves for these upcoming exhibitions, we revist a 1989 interview excerpted from Phaidon's Speaking of Art: Four Decades of Art in Conversation (2010) , in which British conceptual artist and critic William Furlong speaks with Ilya Kabokov on his work The Untalented Artist and Other Characters at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The two discuss the constant flux and uncertainty as to whether a structure is being constructed or destructed, the way that people maintain their personal selves in a communal environment, and the practice of leaving questions unanswered.

---

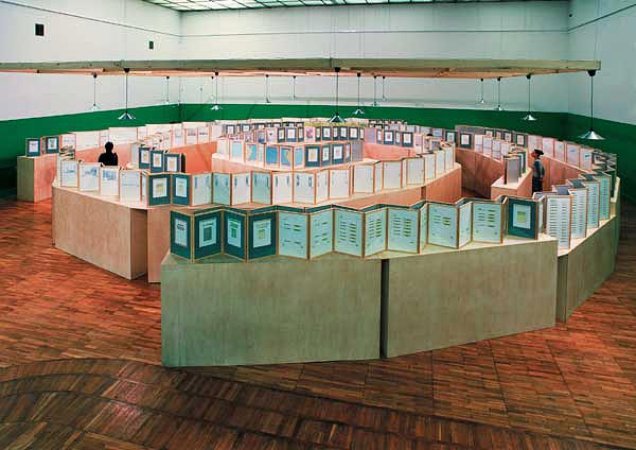

Ilya, we are here in your installation The Untalented Artist and Other Characters . It consists of a series of room spaces that have been cordoned off and subdivided. In the exhibition catalogue you talk very vividly of Soviet apartments and you clearly have a very strong relationship to the experience of living in apartments in Moscow.

I don't want to depict the reality of a communal apartment and the details of living in one. This piece is not actually intended to represent the real thing. It is more generally a question about a person having to live in a space of four walls, and how he/she actually has contact with other people in this situation. In one respect, it is a perfect situation for constant exchange and contact, being always surrounded by other people. But individuals have to find some way of maintaining their personal selves, separate from this huge sea of people around them. This communal apartment is more of a depiction of how a person mixes with, and protects the self from, the surrounding others.

The Untalented Artist, 1998

The Untalented Artist, 1998

So in a way the apartment is merely being used metaphorically as a way of exploring the human condition. The installations here seem to be inhabited by, on one hand, comic characters and, on the other, very tragic characters. There is, however, a sense of the private, of withdrawing into a private space.

Another important metaphor in the situation of a communal apartment is that nobody chooses his or her neighbors. They are just thrown together and they have to live with them as they find them. The communal apartment generally divides into two parts—the separate rooms where people live privately in their own area, and the communal kitchen, which is a kind of battleground where there is constant exchange and contact. Sadly, there isn't a communal kitchen in this particular installation, as it doesn't have a part to play.

Let's walk through to another part of the installation. This interior is entitled The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment , and it is rather like a cell, with a seating contraption that looks as if it could launch somebody. Indeed, there is a hole in the ceiling of this cell that someone could actually have been projected through, and the floor is covered with rubble from the hole in the ceiling. There are also various objects in the room that seem to evoke the earlier presence of a human being.

Every room is like a prison, in a way, to a person. If you live in a room, to get to the outside world seems to be the ultimate desire. If you want to, you can just go out of the room and along the corridor to the kitchen to meet other people. But this outside world of the communal apartment is not adequate for him, and he wants to get right out of it. So the cosmos of space that he wants to get out into is, for him, like some other world, some heaven, some wonderful place of paradise.

The Man Who Flew To Space from His Apartment, Ilya Kabakov, 1984

The Man Who Flew To Space from His Apartment, Ilya Kabakov, 1984

In that respect, it opens up those issues to do with the artist's relationship to the state, which clearly one has to deal with when looking at the work, certainly within this British context.

I don't think that is right, really. I am not arguing, but it is more about an attempt to get into the other world by your own means, and although this character has tried to get into the other world by this crazy invention, it has a kid of pathos because it is obviously not adequate. It seems to us that it is silly and comic and idiotic. On the other hand, when he flew away, nobody found him on the earth afterwards, so it may have been a successful experiment. We have no proof to the contrary. It is an open question.

This next piece is again an enclosure with the title

The Short Man

. I also saw your installation

Ten Albums: Ten Characters at the Riverside Studios in London

where you had a maze of narratives. One thing that interests me is the way in which what are clearly autobiographical experiments are expressed through a third party.

This room has three characters. There is the Short Man, who put the thing together and who composed it. There are my drawings. And there is another character, who thought up the installation as a whole. So there are three characters working all at once, and it is not clear who is the main character—whether it is one of those who have been invented, or whether it is the further character who emerged and created the whole.

Ten Albums: Ten Characters, 1986

Ten Albums: Ten Characters, 1986

We are standing now in the main section of the gallery which, rather as at Riverside Studios, you haven't been content to leave as the almost shrine-like space that it normally is. You have actually painted the gallery interior rather like an institutional building, with color extending halfway up the wall, and there are paintings leaning against the wall. Can you talk a little bit about this sense of the unfinished?

This uncertainty, about whether something is in the process of being built or in the process of being taken apart and thrown away, is very elemental in the way the communal apartment functions. There is a sense of movement all the time and of never knowing in which direction you are going. When I put this installation together, I never really knew whether it was going to be taken down. At what point that feeling begins is also unclear, because when you are building something there is always rubbish, and the rubbish is very much a symbol of this uncertainty of movement. The rubbish not only is a symbol of destruction and of entropy but also has a particular potential, because all these people's lives are basically a clutter of things that they have drawn out of the rubbish to make their lives. So rubbish has a capacity to go either way. It is neutral, but it is a symbol of construction and deconstruction. There is always the chance that nothing but a lot of rubbish comes out of it!

We are now in the space between the galleries upstairs at the ICA. This work, The Composer Who Combined Music with Things and Images , reminds me of one of the stories in the book of a concert in the corridor of an apartment and the ensuing complaints that were documented. Perhaps you could elaborate?

The piece is about this character who is very upset because people are just not interested in washing up their saucepans and running around and not actually thinking about culture or having any cultural part in their lives. He wanted to force or encourage them to think about something more highbrow, and so he got them all together to sing as a choir and put together this combination of pictures and texts. It was very difficult to stop people rushing about and to get them together, so he stopped them by actually putting up stands in the corridor. It was a way to compel them to join in. Terrible rows occurred and fights took place, and it is a fable about how people drive one another to their deaths.

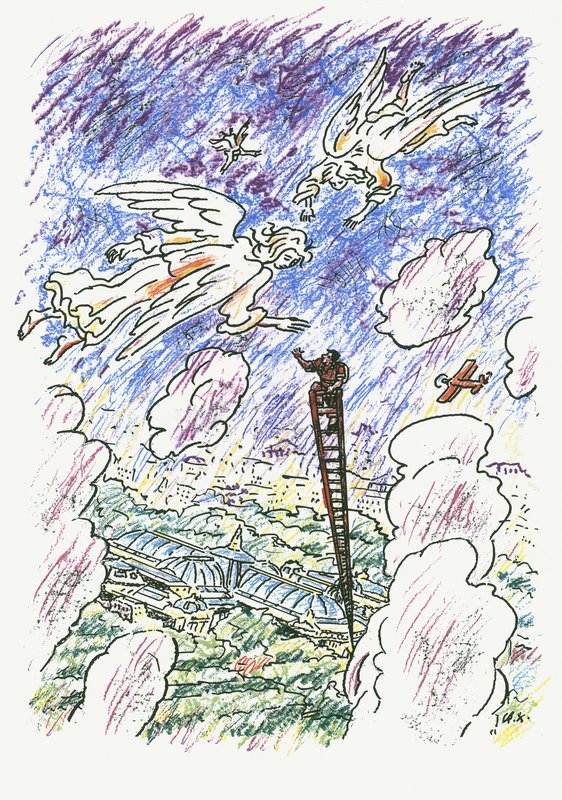

How to Meet an Angel, Comment Recontrer Un Ange,

2014, available for purchase on Artspace

How to Meet an Angel, Comment Recontrer Un Ange,

2014, available for purchase on Artspace

What I find very interesting about the work is that, although it is clearly derived from a very specific experience that is removed from a Western audience, it still seems to me to speak in a universal language in relation to the human condition through the use of metaphor and symbol. It deals with issues such as private spaces as opposed to overwhelming social and political pressures. There is a sense of private, personal survival being investigated here.

There were problems with the installation. It was very difficult to get people to understand what a communal apartment was and why, if it was so awful, people actually lived in it. But there is definitely some consideration of these more general issues here. It is a very successful metaphor of human life and existence, which can't really be conveyed in something abstract. It has to be portrayed in something that the artist knows extremely well as a reality. If you have pure metaphor then it loses its bearing on anything real, whereas if you use something that is straight from reality then it will seem too autobiographical and not referring to other things. I hope this installation has somehow fallen between the two.

How would you locate yourself within Soviet art?

Avant-garde art suddenly came to an end, and then there was a Socialist Realism, which came to its own end as well. Then, at the end of the 1950s, unofficial art emerged, and I see myself as part of the unofficial culture. Some people see that as having already come to an end now. These three different movements have been directly connected one to the other.

It's interesting, the idea of unofficial art, because if there ceases to be an 'official' art, then what is the 'unofficial'?

Official art has always existed and it always will. It just has a different name.