The following is excerpted by Phaidon's newest release, Vitamin D2: New Perspective in Drawing.

Vitamin D2

is available on Artspace for $39

Vitamin D2

is available on Artspace for $39

Vitamin D2 gives a sense of the vitality and energy of drawing today. The accomplishment, dedication, fascination, inventiveness and sheer pleasure taken in mark-making and image-making demonstrated in the featured works suggest that drawing is as dynamic a medium as ever, and that artists continue to consider drawing an essential vehicle for addressing and interacting with the world today.

It used to be commonplace to consider drawing as a daily practice. In everyday life we afford drawing a place in the continuum of activities that go almost unnoticed, from telephone scribbles (for a certain generation, perhaps, when landlines prevailed) to the ubiquitous children’s drawings so often brought up as the paradigm of accidental meaning, from laundry lists to mapped directions. In her introductory essay to the previous edition of this overview of current drawing practice, published in 2005, Emma Dexter insisted on exactly this ubiquity: she defined drawing’s nature as a universal human endeavour, a shared visual language of expression. We use drawing, Dexter writes, "pragmatically to sketch our own maps and plans, but we also use it to dream—in doodles and scribbles. We use drawing to denote ourselves, our existence within a scene: in the urban context, for example, graffiti acts as a form of drawing within an expanded field." The continuity between ourselves and the larger world is expressed through drawing, through marking it, inscribing ourselves into it, through tracing it and making a record and index of some of the elements that surround us; drawing is part of life and life is an occasion to draw.

All this leaves drawing revitalized and emboldened, albeit not so overtly conforming to the narrow forms of material and processual experimentation that we have come to expect from the medium. By gradually entering the global stage, drawing is regaining a political urgency and is emerging once more as a direct, simple, often inexpensive medium to which artists turn when other forms are not readily available or are compromised in some way. Drawing’s current immediacy means different things in different places, and we have new histories and contexts to explore and from which to learn. Alternative traditions, cultures and political realities not only mean alternative pasts, or paths, but also force us to see our shared reality in a new light. At the same time, it is clear that drawing retains certain properties in common with work produced a decade ago: luxurious and rich in narrative, performative and processual, impeccably rendered and monumental in scale, drawing remains a practice that offers fresh possibilities to an ever-growing art world.

FIRELEI BÁEZ

Not Even Unalterable Limitations

, 2012

Gouache

and graphite on canvas

Aesthetically, Firelei Báez’s formidable work draws on a variety of sources including miniature painting, the 19th-century penchant for silhouettes, historical representations of the female form, and the postcolonial experience. In her series of pencil and gouache works,

Can I Pass?

(2011), Báez explores the ways in which skin tone and hair texture are bound to social expectations. Taking on the role of ethnographer, the artist photographs herself during a particular month and records her likeness in a series of nearly silhouetted portraits.

The second part of the work’s title, Introducing the Paper Bag to the Fan Test for the Month of June , refers to tests that relate to the judging of skin tone and hair texture. These tests were used historically (though remnants of their power are still evident) to designate a different social class for people of African descent with hair and skin tones that were closer to those of Europeans. By limiting the figure in this series to eyes, skin color, and hair, Báez focuses attention on these three key elements. Perhaps most powerful is the expression in the eyes, which varies from brooding to ecstatic, from subtle to fierce, from indifferent to troubled.

Fantastic portraits include visions of women with fanciful hairdos that seem to be made from eccentric animals and other whimsical organic forms, particularly in examples such as Not Even Unalterable Limitations (2012). A slender neck holds a graceful head, topped with black and white feathers and flowers. The woman’s slight grimace underscores her subjectivity as she all but glares back at the viewer. Adjacent to this body of work, Báez has also produced a number of powerful, over life-sized drawings of female figures in which the body is literally rendered as a site for landscape. Fulsome bodies are inscribed with dense tropical floral patterns or images of the land that take inspiration from Chinese ink paintings. The tattoo-like drawings relate to the ethnic background of the subjects, marking their difference but also their belonging to other racial and ethnic groups. In this way, the body drawings serve as witnesses of migrations that remain under-recognized in the history of constructing a ‘native’ identity. In the series Prescribed Seduction , started in 2012, BaÅLez has combined two contrasting sides of the mass media: published materials and imagery borrowed from the internet. The drawings are rendered on pages appropriated from books deaccessioned by the Cooper Union Library, particularly publications that relate in some way to male privilege. Narratives about the Grand Tour, manuals for engineering and similar works provide the background and the physical support of the drawing. Occasionally, diagrams from these books may become a part of the work. The images feature figures of women adapted from videos posted on YouTube. Caught in the midst of a seductive pose, perhaps part of a dance movement or sensuous gesture, they reject traditional standards of beauty, femininity and social expectations. For the artist, these figures become like the drolleries seen in the margins of medieval manuscripts. Rendered small, they act as challenges to the reduced roles occupied by women in contemporary visual culture. - Rocío Aranda-Alvarado

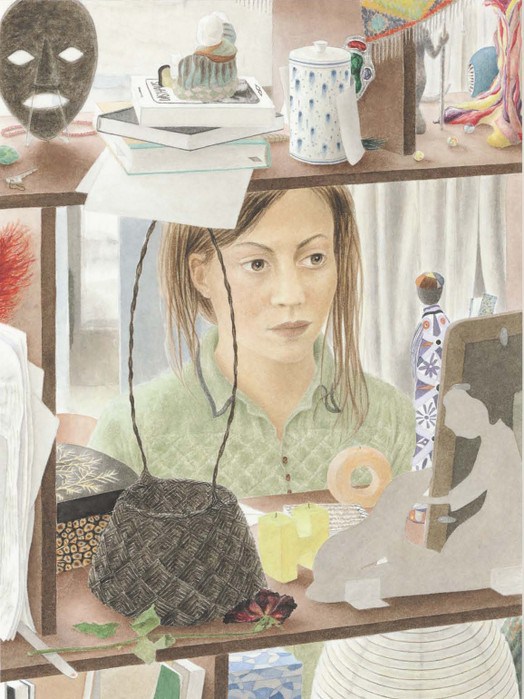

ANNA LEA HUCHT

Untitled

, 2011

Watercolor on paper

Anna Lea Hucht’s work primarily consists of drawings and watercolors, and since 2007 she has also been creating ceramic objects. A central part of her oeuvre comprises drawings of interiors, many of them filled with shelves and sideboards housing a multitude of different objects. These vases, baskets, boxes, plants and figurines are rendered in meticulous detail and betray Hucht’s interest in arts-and-crafts and everyday objects. They seem to be heavy with symbolic meaning that remains hidden from the viewer. The detailed interior scenes, such as Untitled (2011), regularly include human figures, often solitary and lost in thought, whom we can sometimes only glimpse through a shelving structure that separates the protagonist from us like a curtain. The setting’s intimacy adds further to the sense of detachment.

Before Hucht decides on the final composition of her elaborate interior views she draws some parts of the design on tracing paper, which she then places over the unfinished whole in order to run through different possibilities regarding the perspective and layout of the room as well as the position of figures, objects and patterns. The resulting structures seem always just outside of our understanding of a realistic space, capturing and conveying a curious mood.

However, fixed locations seem to be abandoned entirely in her still lifes, which form another important part of her output. The focus of these works is the use of light and shadow as well as the texture of the represented objects. In almost hyperrealistic detail she depicts everyday items ranging from waste-paper baskets to pieces of fabric, from tableware to furniture, all of which appear to exist in an undefined space. Her 2011 work Vorhang (Curtain) is exemplary of the pervading sense of placelessness inherent in this part of Hucht’s oeuvre. The piece shows a close-up of the folds of a curtain, but they are only discernible as such on closer inspection. The sequence of light and dark folds, in conjunction with a horizontal stripy pattern, creates an impression that could at first easily be mistaken for an abstract composition. Nevertheless, the still-life drawings are based on photographs in old books, on photographs made by the artist herself, or are sometimes sketched from life (if she happens to have access to the actual object featured in a photograph). Untitled , a work from 2010 that places such a banal subject as a waste-paper basket in the centre of attention, again illustrates that Hucht’s main interest lies in the representation of varying surface textures and the quality of light. This instance is even more emphasized by the exclusive use of black and grey tones in her still lifes, especially in comparison to her more colourful interiors and outdoor scenes.

Drawings like Einsame Herzen (Lonely Hearts) and Untitled (both 2009) are examples of Hucht’s more whimsical works and display a tendency towards folk themes. Set in a warm and comforting, almost magical world populated by stylized fictional characters, they explore complex human emotions such as flirtatiousness, vanity, loneliness, isolation and longing, in light-hearted narratives.

Hucht captures every aspect of her chosen subject with delicate lines that suggest art-historical and cultural references, with some of her most recent drawings inspired by Japanese woodcuts and Asian scroll paintings. Her impressive technical abilities mix with both a fascination for the everyday and a vivid imagination that leads us out of it. - Carina Krause

RICHARD LEWER

Lewis Street

, 2010

Charcoal on wall

The figure of the ‘artist-as-archivist’ who carefully records and documents historical moments (however minor), is pervasive in current installation and documentary/video art. And, as artists such as Richard Lewer demonstrate, drawing plays a role in developing this nexus of art and archiving. Invested in documenting memories of his childhood, urban myths and soon forgotten news stories, his practice offers a means to engage a range of private and public histories.

In Lewer’s work Principal said “It’s a shame because we have so many kids who do the right thing and the school really promotes respect for each other and respect for the environment” (2011), he represents a subjective interpretation of a crime that took place in 2011 in the regional Australian town of Seymour: three teenage boys bashed a kangaroo to death with steel poles. While news reports stated that the violent act was recorded on a mobile phone, no images of the event were released to the public. Working with the published newspaper reports, Lewer produced an image of the event for posterity. The manifestation of images for otherwise invisible events or seemingly minor histories is a constant in Lewer’s practice, as is an engagement with, and documentation of, what he terms ‘extreme stories’ of crime and violence. In 2005 he began to research news reports on the convicted stalkers Richard Ramirez and Robin Rishworth, producing a range of works including 03-03-09’ (2009), a large-scale wall drawing commissioned by the Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art. To create this work, rather than invoking mass-circulated news reports of such stalkers, Lewer randomly selected a woman in Sydney’s central business district and proceeded to follow her for a day. Based on the hundreds of photographs that Lewer shot during this performance, 03-03-09’ cleverly blurs the lines between fact and fiction.

Lewer oscillates between archiving, and subjectively interpreting, stories that circulate in the public realm via the mass media, and histories that are highly personal. Just as crime is a leitmotif in his work, so are memories and experiences of his childhood in Hamilton (New Zealand), where he was raised in a strict Catholic family. The drawing Father Duggan (2009), a portrait of Lewer’s childhood parish priest, was created as a means to reflect on the role that the priest had in the formation of his early identity. The portrait, like much of his work, is based on a pre-existing document – in this case a photograph rather than a newspaper report – and as always, is mediated by the artist’s subjectivity. His attempts to grapple with his early experiences of Catholicism continue with Pact and The Confession (both 2009). Here, we see Lewer’s subjective rendition of demonology’s symbolism: emotive, abstract images of tormented figures in conflict. Other moments from Lewer’s childhood appear in his large-scale wall drawing Lewis Street (2010), which represents his childhood family home, a 1970s brick veneer building quintessential to the suburban New Zealand landscape (this image reappears in several of Lewer’s drawings).

Working at the intersection of the private and the public, fact and fiction, Lewer takes his subjective, phenomenological experience of the world as his starting point, offering a means to rethink the role of drawing in the production, and recalibration, of the cultural archive.

-Veronica Tello

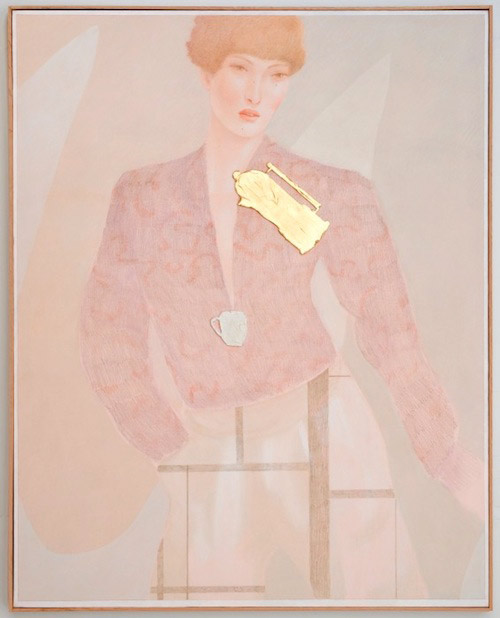

ALAN REID

Black Fish

, 2012

Caran d'ache, tinted gesso and polychrome foam core on canvas

Where did the polysemic relation between physical mass and intellectual or spiritual seriousness in art come from? Why is ‘lightweight’ considered an insult as far as aesthetics and ideas are concerned, when grace and freedom and delicacy are expressions of quality? Texas-born, New York-based artist Alan Reid makes drawings in coloured pencil that are light in palette and light in tone. Often, he composes his figures with a disregard for the forces of gravity, or he floats cut-out, foam-core objects on the picture plane as if they were boats on a pond. The women who feature in his drawings are all slim and strong; one can imagine them gliding effortlessly through a room.These are ‘Pics du sexy’, as the breezy inscription reads in the drawing

Prospect Park

(2012). You could say that Reid makes lightness, in all its semantic guises, his theme. His challenge to the viewer is not to mistake lightness for a lack of seriousness; on the contrary, he has profound things to say about it.

The world of fashion has historically been the victim of condescension by those involved in contemporary art. It is typically seen as a frippery, a thoughtless and short-lived diversion. ‘Fashionable’ is rarely a complimentary critical term. Reid is interested in moments, however, when popular style and self-expression are inseparable from the most rarefied echelons of ‘high art’ – principally, for him, that of mid-century modernist abstraction. In Surface of the World (2012) (a title that itself implies both superficiality and supremacy), for example, Reid’s female subject wears a skirt bearing a pattern reminiscent of paintings by Piet Mondrian. In Backstage Grammar (2011), the design of the woman’s blouse is evocative of certain works by Bridget Riley. Neither case of appropriation is hypothetical; these were popular designs for women’s clothing in the 1960s.

The flatness of Reid’s forms lends itself to being filled in with appropriated imagery such as commercial patterns and quasi-modernist abstraction. His figures are blank canvases, so to speak; they give little away about themselves. In his earlier work, there was often a sense that Reid was scornful of his subjects (he once described them as ‘bored and bitchy’), but in recent drawings his relation to them is much more ambivalent. His use of inverted text in works such as La Collectioneuse and Facade (both 2011) can be interpreted in one of two ways: that these women are gazing at their reflections in mirrors, or that Reid is inviting us to step behind the picture plane and look out at the world through their eyes. By cutting his drawings of their faces into the shapes of African masks (mid-century symbols of exoticism and otherness) Reid gives us the opportunity to don masks of two faces simultaneously. Ours is no longer a detached position of glib criticality, but one of empathy and of uncomfortable implication in the shallow fictions they embody. - Jonathan Griffin

MARY REID KELLEY

Sisyphus at her Toilette

, 2012

Collage, acrylic, and charcoal on paper

Mary Reid Kelley’s drawings are at once stand-alone artefacts and corollaries to, and components within, her darkly antic films. The latter, starring Reid Kelley in multiple roles, are shot in monochrome and replete with Expressionist and comic-strip trappings; entangling temporalities and registers, powered by puns, they’re often imperilled by their own density.

You Make Me Iliad

(2010), borrowing from the mock-epic mode of Alexander Pope, uses 101 rhymed couplets and the relationship between a soldier-turnedpoet and a Belgian whore to explore a veiled history of prostitution on the Western Front, while

The Syphilis

of Sisyphus

(2011), made in collaboration with Patrick Kelley, centres upon Sisyphus, a bohemian

grisette

or workingclass woman in Second Empire France. Her face a hollowcheeked mask, with eyes ringed by glossy black circlets, this fallen woman issues a righteous monologue, highminded but potty-mouthed, on the fate of her sex. After a quartet of harlequin-like saltimbanques have performed playlets concerning major figures from French history, she is then arrested by the ‘Morals Police’ and led off to Paris’s La Salpe^trie`re Hospital, where neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot famously carried out his research on female ‘hysterics’.

This mordant assignment and trans-historical questioning of roles for women is condensed in Reid Kelley’s drawings, which trace the same storylines. (And indeed her films, with their reduction of everything to black and white and sharp illustrational contour, could be seen as transpositions of drawing into live action.) In the gouaches Sisyphus at her Toilette and Keep Coiffing (both 2012), we see Sisyphus reflected in a mirror as she paints her face or brushes her hair, her makeup resembling a clownish skull. Around the edges of the mirrored view, meanwhile, her tumbledown garret serves as shorthand for dissolution. In Morals Police (2012), two frowning male law-enforcers, in top hat and Napoleonic tricorn respectively, pause on an unlovely cobbled street, gazing out with dead-eyed classifying certitude; by now, we know their intent.

‘I think it would be ridiculous to watch the films and not connect them with ongoing violence in the world,’ Reid Kelley said in a 2010 interview, while denying that her works analogize specific events or situations. Her films and drawings, rather, address a generalized history of violence and domination. They also confess their own constructedness, since they’re clearly palimpsests of dramatic communicatory styles, borrowing their lighting from early twentieth-century cinema and painting (from Max Beckmann to Blue Period Picasso), their flattening and graphic reduction from Krazy Kat et al, as well as from theatrical backdrops or illustrations, their speech rhythms from Homer and doggerel verse, their distantiation techniques from Brechtian theatre.

Reid Kelley can condense feelings about oppressed and oppressor into a single drawn image, such as a sombre Sisyphus raising her skirts before a sign reading ‘SILENCE’ ( Sisyphus on Staircase , 2011). Her wordplay, however, can outpace comprehension, since for all its forcefulness, Reid Kelley’s art wants at once to speak, to use linguistic rupture against the authority invested in the word, and to clarify the limits of what it can say and do against the historical drift it addresses. Accordingly, insofar as she laments domination and specifically the role assigned to women down the ages, easily consoling pabulums are refused. If Reid Kelley’s work has only recently evoked the endlessly struggling Greek king by name, Sisyphus has been its daystar all along. - Martin Herbert

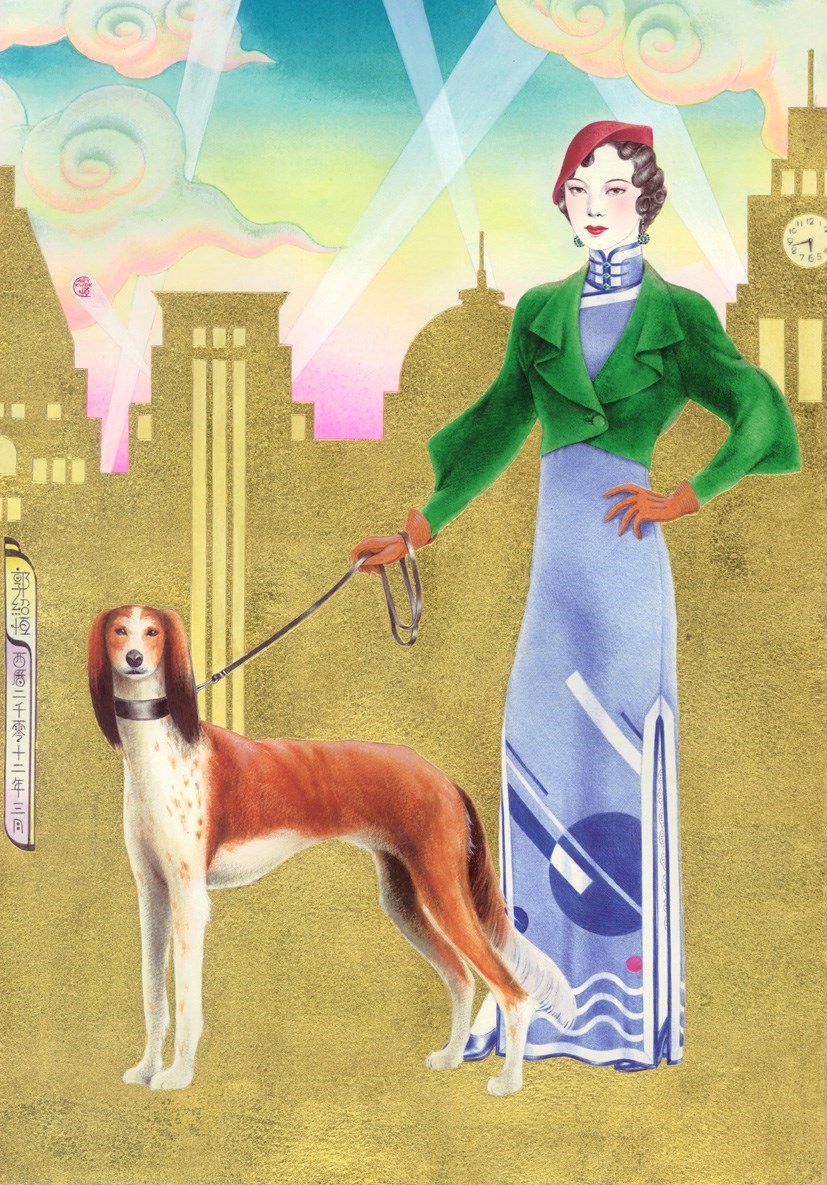

CARY KWOK

Qipao - Shanghai (1930s)

, 2012

Ballpoint pe, acrylic, gold leaf, plyester glitter, and PVA adhesive

If you were only to see Cary Kwok’s most tasteful exercises in virtuosity – his ballpoint pen and acrylic paint works depicting intricate chinoiserie dresses, wonderfully architectural tresses of hair, ladies’ shoes to die for – you would only have seen half the picture. For Kwok’s most notorious and most striking work is sheer X-rated porn, with a gleefully irreverent twist: images of men (Jimi Hendrix, a man wearing a dog-collar, Tintin, Superman) showering themselves and each other in great, streaming jets of cum. Conversely, of course, if you were to only see these quite literally blue images (Kwok uses blue ballpoint pen to startling effect), you would also only have half the story: Kwok’s drawings are both incredible works of illustrative skill, and a wickedly levelling trawl through the iconography of fashion, art and pop culture.

Born in Hong Kong and based between Hong Kong and London, Kwok takes an interest in identities that is both celebrative and deconstructive. As a child it was his dream to become a designer of clothes or shoes, and he went on to study fashion at Central Saint Martins. Shoes and hair are motifs that appear in his work as frequently (perhaps more so) as his more explicit motifs. (He is also an excellent hairdresser, although he is quick to note that he is not a ‘pro’.) Drawing is Kwok’s true métier , and it is the mixture of sheer graphic skill and a casual sensibility – often punning and sometimes deliberately puerile – that marks these images as within the realm of artistic discourse.

Kwok has stated that ‘in my work I am always trying to make a point of racial, ethnic, sexual or gender equality.’ There is, certainly, a perverse sense of equity in the range of male figures that he depicts (the Cum to Barber series features a healthy mix of black, Asian and white celebrities and working-class men). This cross-cultural levelling is true also of his subtler, more encoded works. For example, in the Plumage series from 2007 onwards, Kwok creates a common grammar of hair-obsession between ancient Greece, ancient Rome, Tang Dynasty China, pre-Revolutionary France and presentday America. The images are extraordinary, intricate and joyous.

Disjunction is also a key aspect of these works, with frequent shifts between the sublime and the ribald. Of course, in such a game of surprise, one might easily paint oneself into a corner. The most subversive tactic might then be the sumptuous loveliness of the Qipao series of 2012. This series is, in many ways, educational: each image guides the viewer through the changing politics and style of traditional Chinese women’s dress, from the courtly outfits of the 1910s through the militarized look of the 1940s and the westernized neo-punk style of the 1990s. The message: don’t be so shallow as to think that fashion is all surface, or that surface is unimportant. - Colin Perry

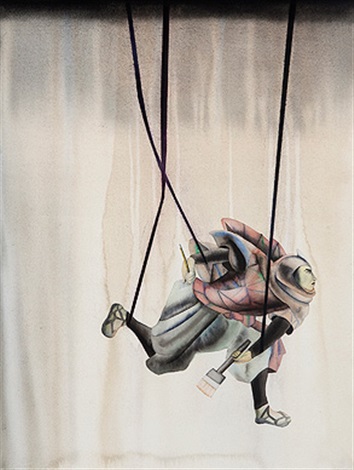

ANJU DODIYA

Violet Ribbons, 2010

Watercolor, charcoal and soft pastel on paper

Anju Dodiya’s preferred subject is the self-portrait, but her relationship to self-portraiture has been a troubled one. She embodies a post-Cartesian self whose radical doubt is articulated as an inquiry into the mind’s phantasms, the body’s afflictions. Since the mind cannot be trusted, it erupts in nightmares, tempts the self into performing a masque of avatars. As for the body, the skin changes colour without warning, scabs break out on the alabaster smoothness of the face. Every self-portrait that Dodiya makes is a condition report, a chart of symptoms.

Dodiya, who lives and works in Bombay and held her first solo exhibition in 1991, is an exquisite watercolourist. She has extended the medium both in terms of its scale and its potentialities. Scorched by charcoal, her painted surfaces float in pools of water and light. Drawing is a mode of conception for the artist: it signifies the haptic gift of grasping not only the world around her, but also the vivid fantasies that possess her.

In the private theatre of her paintings, Dodiya performs certain insistent kinds of self-dramatization: she plays, variously, magician, martyr, samurai, seductress, hypnotist and stunt-woman. What binds these performances together is her fascination with extreme situations embodying allegories of painting: she enters her own frames either to kill or to set free, performing acts of relentless cruelty alternating with a desire for impossible freedoms. For Dodiya, the studio is a mutable conceptual space in which stills from world cinema, quirky newspaper photographs, reproductions of medieval tapestries and ukiyo-e prints jostle for space. It is a transcultural archive of starting points and references that she constantly consults and replenishes.

Melodrama and caricature, carried to the point of a melancholic self-awareness, activate Dodiya’s artistic callisthenics. In Face-off (After Kuniyoshi) (2010), she models her protagonist on the figure of the samurai who features in Japanese midnineteenth-century ukiyo-e prints. Her samurai is a mock-heroine who has pledged her fealty to the act of painting, taking her stand on the yet-unvanquished bastion of art. In Surge (2010), the artist-samurai battles a gigantic sea monster that imposes itself between her and the canvas. Its distended eyes, swimming in a mass of flesh and pincer-claws, trigger a nightmare of entrapment in one’s own uncontrollable fictions.

In her recent series, Mirage of Flags (2012), a grid of miniature images, Dodiya returns to her earlier works, testing their endurance when confronted with the ravages of time and the mind. The grid is made up of a series of twinned images. In each pair, the first image is a photograph from the artist’s personal album, either showing her in a museum context, looking at works by the great masters, or performing some simple ritual of daily life, like unfolding a towel. The companion image in each pair is a photograph of one of Dodiya’s own works, a reproduction that has been stained, fogged, sometimes nearly erased. Taken together, each pair articulates the feedback loop of a life led in and through art, its continuous processes of learning and experimentation, pleasure and torment, secrecy and self-revelation. - Nancy Adajania