Historically made to embody strength, power, and virility, the male nude can also evoke beauty, vulnerability, and sexual intrigue. As we discussed with the photography critic Philip Gefter , these images of the body have the potential to challenge taboos around male eroticism and identity , paving the way for future explorations of what it means to be male. This list, excerpted from Phaidon 's new book Body of Art , includes examples from monumental 17th century chalk drawings and Enlightenment-era scientific models to contemporary hyperrealistic sculptures—all proudly owning their nakedness.

Click here to learn more about Phaidon's Body of Art and buy the book .

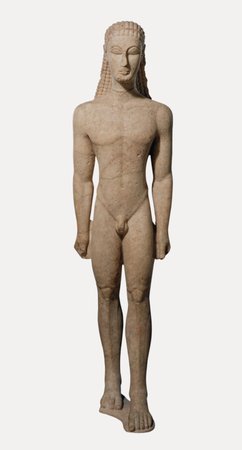

KOUROS BOY

Artist Unknown

c. 600 BC

The kouros ("youth"; pl. kouroi) statue is the earliest Greek monumental sculpture type of the post-Bronze Age, and this example in New York’s Metropolitan Museum is one of the earliest. The inspiration is Egyptian: these early kouroi employ the Egyptian grid of proportions and the canonical frontal pose, with arms at sides and left leg advanced. Indeed, this early kouros is the only extant example that perfectly matches the Egyptian canon of human proportions as described by the Greek historian Diodoros in the first century BC. The Greek works differ from Egyptian figures, however, in being nude and carved in the round. Moreover, the decorative traditions of the preceding Geometric period (10th–8th centuries BC) can be seen in the patterns used to represent the essential elements of the human form: here, the curves of the pectorals are repeated in the kneecaps and eyebrows, and the angles of the ribcage are reflected in the elbows and groin. Stylization of hair and facial features extends to the fat cheeks, wide eyes, arched eyebrows and spiral ears. Over the next century sculptors would integrate these patterns into a more naturalistic whole, resulting in the much more subtle and relaxed form of the last of the kouroi, the Kritos Boy.

FARNESE HERCULES

Glykon

Early 3rd Century AD

This massive sculpture of the Greek hero Herakles (Latin: Hercules) was commissioned for the baths of Caracalla in Rome, which were dedicated in 216 AD. Signed by Glykon, the work is probably an enlarged copy of a fourth-century BC bronze original by Lysippos. Leaning wearily on his club, cushioned by the skin of the Nemean lion, Hercules’ exhaustion is explained by the two apples he holds behind his back – the apples of the Hesperides, a labor only accomplished by his agreeing to hold up the heavens while Atlas picked the fruit. The sculpture embodies power taken to its limits – the world’s strongest man almost defeated by the literal weight of the world. The statue was discovered in 1546 and added to the collection of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III. It was restored using legs carved by Michelangelo’s student Guglielmo della Porta ( fl .1534–77), and in the 1590s Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) frescoed its room in the Palazzo Farnese with riotous paintings of Hercules’ life and labors. The original legs were discovered not long after, but Michelangelo advised that Guglielmo’s versions be retained as examples of modern work that was equal to that of the ancients. The ancient limbs were not restored to the statue until 1787, and even then Guglielmo’s legs were displayed next to them, as they still are today.

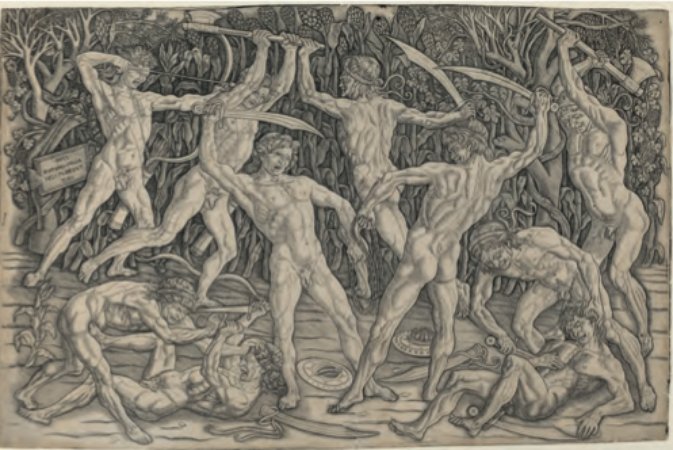

BATTLE OF THE NUDES

Antonio Pollaiuolo

c. 1470

This study in human motion is an astonishing display of flexed muscles and straining sinews amid manic slaughter, of bodies engaged in energetic action seen from different angles. A versatile and influential artist, Antonio Pollaiuolo’s (1432–98) main interest was in human anatomy, and his scientific knowledge of the body greatly impressed his contemporaries. In Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari wrote that Pollaiuolo "understood the nude in a more modern way than his predecessors; he flayed many men to see their underlying anatomy, and he was the first to show how to seek out the muscles, which should have form and order in figures". However, Pollaiuolo’s exaggerated depiction of musculature is not altogether accurate. He may indeed have been one of the artists that his younger contemporary Leonardo da Vinci had in mind when he complained that certain artists’ nudes appear "wooden and without grace, so that they look like a sack of nuts or a bundle of radishes rather than surface of a human being".

TAINO STOOL

Artist Unknown

c. 15th- 16th Century

The art of the indigenous Taino people of the Caribbean was predominately associated with shamanistic ritual and religious beliefs. Hereditary chiefs and shamans (often the same person) communicated with the spirit world by inhaling an hallucinogenic powder called cohoba. This low stool (or duho, as it was called by the Taino) was used in the cohoba ceremony and is carved in the form of a spirit being ( cemi ). The male figure is contorted, his clenched fists pressed to his face and his toes clawed, clearly in the grip of the mind-altering drug. The underside of the stool reveals a skeletal ribcage that reinforces the association with dead ancestors, while the displayed sexual organs relate the cemi to traditions of male potency. The lower legs possess exaggerated, hardened calves (another symbol of male strength that the Taino produced by binding their lower legs with ligatures), which are here decorated with curvilinear designs. The skull-like head on the upper side of the duho, elongated as a result of more binding, has empty eye sockets and a gaping mouth that further link the cemi with the ancestors. The stool was presented to the explorer William Frederick Webb, who passed it on to the British Museum because of its "indecent nature".

CERNE ABBAS GIANT

Artist Unknown

Probably 17th century

The Cerne Abbas giant is as controversial as it is explicit: no definite date, identity or purpose is agreed upon. It was created by cutting an outline into the turf and infilling with white chalk. Although considered ancient by some, the earliest record of it dates to 1694, when it was old enough to need repair; a land survey of the area in 1617 makes no mention of it. Eighteenth century antiquarians associated it with a Saxon god or the Greek hero Hercules, whereas others suggest that it satirized Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658, leader of the English Civil War and sometimes referred to as "England’s Hercules" by his enemies). Investigations in 1996 and 2008 confirmed that the giant once held a cloak or animal skin over his left arm, suggesting the figure is a hunter or perhaps Hercules carrying the skin of the Nemean lion. Historical depictions reveal that the 35-foot erection seen today dates to the nineteenth century, when a circle representing the navel was joined to a smaller penis. The phallus was prudishly omitted from Victorian images of the giant, but the figure’s association with fertility flourished. Local folklore decreed that sleeping on the figure would make a woman fertile, and that infertility would be cured if sexual intercourse took place atop the phallus.

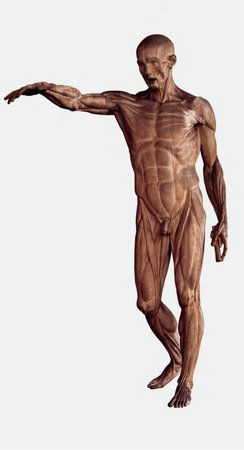

FLAYED MAN

Jean-Antoine Houdon

1767

This life-size sculpture of a flayed man shows the intricate system of muscles that lie beneath the skin. Houdon (1741–1828) made the piece when he was still a student in Rome, aged just 25. It is one of his earliest and most famous works, and has been reproduced thousands of times, serving as a popular anatomical model for artists. Houdon had been commissioned to create a sculpture of John the Baptist and, after being given the opportunity to study human anatomy with a professor of surgery, decided to create an écorché (an anatomical model) that would help him accurately represent the bone structure and musculature of the saint’s body. His study was highly praised by his anatomy tutor as well as his fellow students, who urged him not to modify it further. The sculpture was soon bought by the Académie de France in Rome, where it became required study for subsequent students; copies were soon to be found in art academies all over Europe.

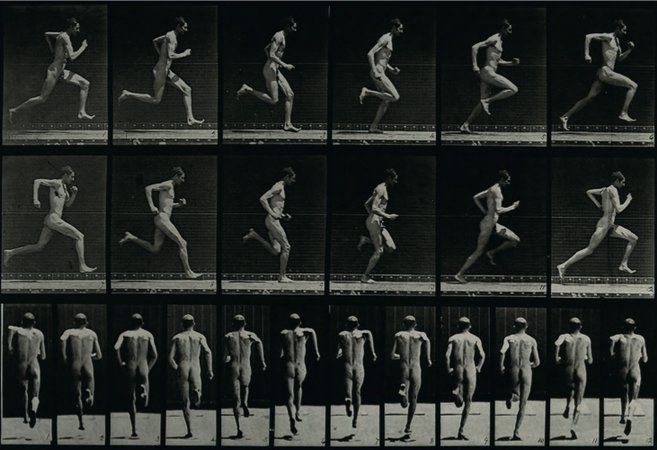

A MAN SPRINTING

Eadweard Muybridge

1887

These 24 photographs showing a man running are among the first to successfully capture the human body in motion. They form part of Muybridge’s (1830–1904) "Animal Locomotion" series, which was commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia in 1873. Working with professors of physiology, engineering and anatomy, Muybridge spent four years on the project, creating 24,000 photographs, of which 781 feature men and women performing common actions. Custom-built cameras with electrical shutter mechanisms allowed Muybridge to take multiple exposures in sequence at regular intervals. The university constructed an outdoor studio with cameras placed so as to capture subjects from the side, front or back, and from a 45-degree angle. The A Man Sprinting photographs demonstrate the action and movement of the human body’s limbs and muscles in a way that had previously been impossible. Although originally intended as a scientific study aid (as indicated by the anthropometric grid behind the subject), the photographs of this anonymous runner have transcended their original context to become iconic images in the history of photography, and they represent an important step in the development of cinematography.

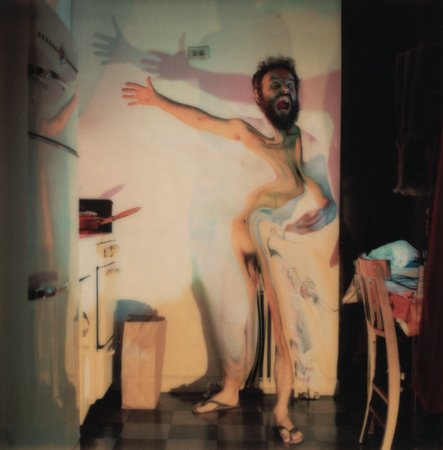

PHOTO-TRANSFORMATION, JUNE 13, 1974

Lucas Samaras

1974

Armed with a simple Polaroid camera, Lucas Samaras (b.1936) created a series of innovative and grotesque self-portraits in the tiny, confined space of his New York apartment. The emulsion of 1970s Polaroid film, protected under a layer of Mylar, remained wet and malleable for up to 24 hours (a feature Polaroid later corrected). After removing the Mylar, Samaras could manipulate the emulsion with a stylus or his fingers to create fantastic, often gruesome effects. Colored light and double exposures helped to heighten the drama of the distorted bodies he created. A visceral wave seems to ripple through the figure in Photo-Transformaton, June 13, 1974 resulting in impossible anatomy and at times blurring the boundary between the body and its environment. In the words of critic Donald Kuspit: "Details of the body may stand out, but the body as a whole dissolves into an undifferentiated flux, rhythmically moving but amorphously chaotic." With a confrontational glare and screaming mouth, the figure delights in shocking the viewer with his body’s horrific form. In light of the viewer’s expectation that a photograph will faithfully represent reality, the Polaroid’s unassuming size and the mundane kitchen setting, the image of this figure delivers an unexpected fright.

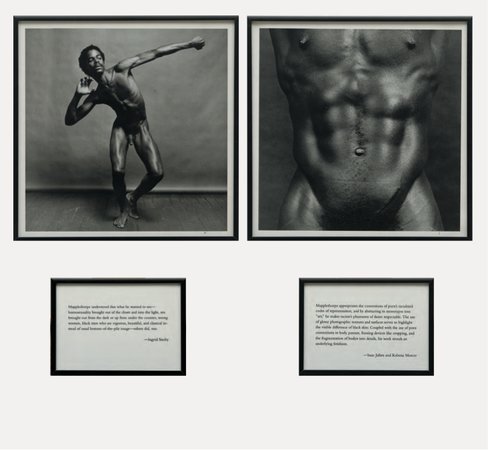

NOTES ON THE MARGIN OF THE BLACK BOOK

Glenn Ligon

1991-3

Using found sources, and foregrounding race and sexuality, Glenn Ligon’s (b.1960) text paintings, photographs, videos and installations examine the complex experience of being black in the USA. Robert Mapplethorpe’s Black Book, featuring highly aestheticized studies of nude black men, caused an uproar when it was published in 1986, as much because the photographer was white as for its homoeroticism. Ligon had very ambivalent feelings about the book and eventually began to create his own work in response. His Notes on the Margin of the Black Book started as a drawing project, but he soon realized that in order to comment on Mapplethorpe’s photographs he needed to use the actual images. Ligon took Mapplethorpe’s book apart, framed the pictures and juxtaposed them with short texts: quotes about the illustrations, the history of the representation of black people and issues of censorship and homophobia. He added commentary from people he had interviewed about the Black Book, including some of the men who had posed for the photographs. In providing a context for Mapplethorpe’s photographs, Ligon’s aim was to "let the viewers sort it out". The viewer may choose just to look at the photos, or to read the texts as well and experience Ligon’s process of thinking about the work.

DEAD DAD

Ron Mueck

1996-7

Australian artist Ron Mueck (b.1958) shot to fame in 1997 when this hyperreal sculpture of his recently deceased father was shown at "Sensation", an exhibition of works owned by the British collector Charles Saatchi. The disarmingly life-like naked body lies with palms facing upwards and sunken eye sockets flushed pink. Every detail, from the imperfections of the man’s skin and the wrinkles on the soles of his feet to his hair (Mueck’s own) is absolutely accurate. The only anomaly is the figure’s size: at just over 3 feet long, it is little more than half life-size. This unexpected distortion of scale is what gives the sculpture its emotional charge, the miniaturized body appearing strangely child-like and vulnerable. Mueck’s father was a toymaker, and the artist grew up making dolls and costumes before working as a puppet-maker for television, film and advertising. Since turning to sculpture in 1996, he has maintained an extremely high level of craftsmanship, applying skills more often associated with theatrical or cinematic special effects. He works painstakingly with clay maquettes before sculpting his figures, often based on members of his family, in fiberglass, silicone or resin. As Mueck says, however, "although I spend a lot of time on the surface, it’s the life inside I want to capture".