The last three years have been a whirlwind for the Colombian artist Oscar Murillo. He graduated from London’s Royal College of Art in 2012, signed to David Zwirner the following year, and subsequently became the subject of heated art world debate when his prices rocketed (in some cases by as much as 3,000 percent). While his prices have since fluctuated, a painting of his earned his fifth-highest price at auction last month when it sold for $374,395 at Christie's London; just this week, another painting sold for $245,000 in the 20th Century and Contemporary Art day sale at Phillips in New York.

Not surprisingly, Murillo’s rapid ascent has been met with some—make that quite a lot—of pushback. The art advisor Allan Schwartzman declared, “Almost any artist who gets that much attention so early on in his career is destined for failure.” The critic Jerry Saltz dismissed Murillo’s debut show at David Zwirner in New York last year, “A Mercantile Novel,” as “student work." There are also more market-driven mutterings about Murillo’s long term “viability,” and insinuations that celebrity collectors (among them Orlando Bloom and Leonardo DiCaprio) have played an outsize role in his success.

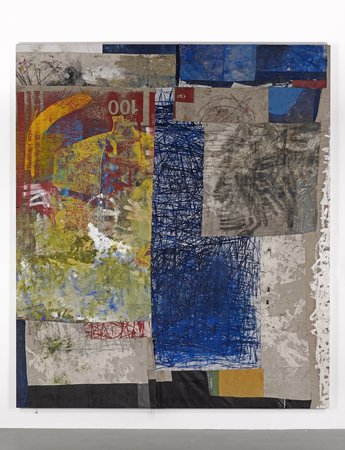

HSBC, pork pashtuk, 2014-2015. 114 1/4 x 98 1/2 x 15/8 inches (290 x 250 x 4 cm) Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

What tends to be missed, in all of this, is the personal and unpredictable nature of Murillo’s work. Despite the wild speculation that surrounds him, he doesn’t appear to be making art for anyone but himself—to judge from his latest show, “binary function,” at Zwirner in London (through November 20). Murillo is also participating in this month’s Performa 15 festival in New York; his commissioned project Lucky dip, which runs from November 16 to 22, takes place at the U.S. Customs House in Lower Manhattan and consists of performances and installations on the topics of trade, globalization, and capital.

The Zwirner show, in particular, addresses Murillo’s feelings of geographical and cultural displacement (he emigrated to the U.K. from Colombia at the age of 10) and, to a lesser degree, the potentially life-transforming side effect of his rapid ascent (he’s not yet 30, and is only a few years removed from his former, low-key life as an office cleaner and a gallery installer.)

“Binary function” includes painting, drawing, sculpture, sound, and an approximately hour-long film called meet me! Mr. Superman that was shot on New Year’s Day in Murillo’s hometown of La Paila, Colombia. This last piece, the film, is perhaps the most affecting. Street sounds with Brian Eno-esque annotations follow you up the gallery stairs into each room, a subtle, aural reminder of what Murillo has left behind and what might lie ahead for him.

Installation view from the 2015 solo exhibition "binary function" at David Zwirner, London.

He shot the film footage a few years ago. It features a bunch of friends who have been up all night and find themselves in the street, a little worse for wear, at seven o’clock the following morning. “There is this sense of continuing the celebratory process,” he says. “It’s an immersive kind of thing and brings back memories of my own enjoyment. I never considered it as a film I would show to the world, as it’s very insular. But the score that was composed for it opens it up and becomes a kind of bridge to the world.”

In the film one of Murillo’s friends wears a Superman t-shirt, something the artist immediately trains his camera on. “The superhero is such a Western symbolic ideal of the perfect kind of human being,” he says. “I’m not a Western subject, so I’m saying meet me Mr. Superman. I’m meeting you, I’m giving you my context—this is where I’m from. This is what I do.” He continues, “It becomes a nostalgic reference point, because my kind of non-western identity has begun to erode since I left that culture.”

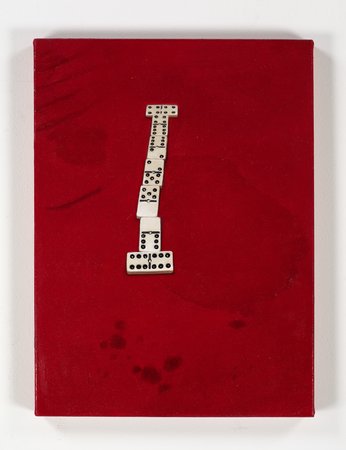

While this longing for home and for the past is most evident in the film, it’s there too in the painting binary #1. This work makes reference to the game of dominoes, which Murillo played with his grandmother and which, he says, is a soothing pastime for many Colombian emigrants. His uncertain relationship with his new world, meanwhile, is implicit in his painting of the Regency-style interior of a collector’s home in Bogota (he visited at a curator’s behest, while preparing for a show there last year.)

binary #1, 2015. Oil on canvas, 15 3/4 x 11 7/8 x 7/8 inches (40 x 30 x 2 cm). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

Depicted within that painting is another painting—an image of a boy hauling fish that, together with the fancy décor of the collector’s home, makes up another of the show’s binaries. “I saw this watercolor painting of a boy with a tub of fish on his shoulder,” Murillo recalls. “The experience of seeing that painting became a kind of foundation for the show in Bogota. The show used that experience to continue this conversation about my own eroding history and this new identity that I’m beginning to handle, not just as an artist but personally too.”

Installation view from the 2015 solo exhibition "binary function" at David Zwirner, London.