One week in, the Museum of Modern Art’s “Picasso: Sculpture” show is already shaping up to be the critic-approved blockbuster of the season. Yet it shows us a Picasso we rarely see in other exhibitions of this scope—and not just because many of the works are making their first appearance in this country.

For one thing, the steady pulse of biography that's become a standard of Picasso shows is all but imperceptible here. Picasso’s sculptural production was scattershot, in contrast to his constant drawing and painting, and the show’s curators have had to work around decade-long breaks. The galleries unfold chronologically, but not in orderly sequences of muses or rivals or residences. Contingency and collaboration are key; we’re made aware of the experiments with Braque that contributed to the celebrated Guitar, as well as the bits of scavenged material that evolved into sculptures.

Along the way, Picasso’s multicultural and pan-historical influences assert themselves even more forcefully than they do in his paintings. In addition to the Iberian and African sculptures that show up frequently throughout Picasso’s oeuvre, visitors can spot hints of Cycladic art figures, Greek koroi, Etruscan bronzes, and Asian ceramics.

Perhaps the show’s greatest surprise, though, is the modest scale of many of the works: true-to-size apples and absinthe glasses, wispy stick figures made from splinters of canvas stretchers, kitchen fixtures repurposed as itsy-bitsy readymades, pebbles with faces carved into them, even a scaled-down horse made as a toy for one of Picasso’s grandchildren. These works are informal, even offhand, but it would be a mistake to call them humble: they’re as brash and confident as any of Picasso’s large paintings.

Below are a few of these minuscule but not-to-be-missed works.

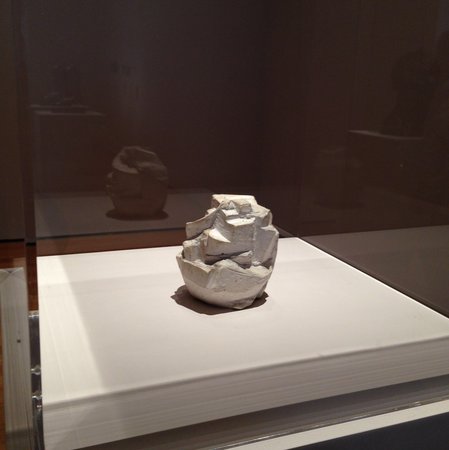

APPLE

1909

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Along with the more famous Head, this palm-sized delight marks Picasso’s transition into Cubism. (In the exhibition, it’s the last work you encounter before moving into the gallery of guitars and absinthe glasses.) Made while Picasso was exploring the hillside village of Horta de Ebro, it has pronounced facets and crevices that render it as much a landscape-in-the-round as a piece of fruit. At the same time, there’s a hint of the edible in the modeling process; Picasso carved the plaster with a knife, “not unlike the way in which one might slice into an actual apple,” as the catalog reminds us.

GLASS AND NEWSPAPER

1914

Musée national Picasso-Paris

The year 1914 was a watershed for Picasso, a period that gave rise to his cardboard and metal guitars and the various versions of his cast-bronze absinthe glasses (which have been reunited at MoMA for this occasion). During this exceptionally fertile period, he was also working up boxy little relief sculptures with a closer relationship to his still-life canvases. Glass andNewspaper—scarcely bigger than a Joseph Cornell, and just as intimate in mood—is typical, sharing the green background and yellow and black speckles of a painting in MoMA’s collection.

METAMORPHOSIS II

1928

Private collection

After a 14-year break from making sculpture, Picasso was inspired to return to the medium when he was commissioned to create a monument for the tomb of the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who had been a close friend and an advocate for Cubism and Surrealism. The process wasn’t easy; the memorial committee rejected design after design. This hyper-sexualized little bronze figure evolved from one of the rejected drawings, and its various misplaced orifices and bulges exude defiance—even as the biomorphic lines of the overall figure seem to represent the more graceful side of Surrealism.

STANDING WOMEN

1930

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Carved with a penknife from canvas stretchers and scavenged wood, these attenuated female figures may remind you of Giacometti’s spindly standing men and women. (Both artists, it’s thought, were looking at Etruscan bronzes). At MoMA, they share a gallery with Picasso’s better-known and more voluptuous sculptures in plaster; both bodies of work were made at the artist’s Boiselegoup studio, in the early 1930s, and both were photographed by Brassai. Picasso later cast some of the Standing Women in bronze, but the wood carvings reveal his profound responsiveness to materials; often he used the knots and grooves of the wood to suggest bodily features or draped fabric.

WOMAN WITH LEAVES

1934

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Found objects pop up in “Picasso: Sculpture” as early as the Cubist period (note the absinthe spoon), but in works from the mid-1930s they’re often incorporated into sculptures in the form of casts. Here, Picasso undercuts the classical pretensions of a laurel-wreathed figure with multiple imprints that make the piece look like a choppy assemblage: it has a strange little piece of hardware for a head, a toga made with corrugated cardboard, and a sash of beech leaves.

THE VENUS OF GAS

1945

Private collection

In addition to casting found objects and working them into larger sculptures, Picasso pressed them into service as assemblages and readymades à la Duchamp. He seems to have done so with remarkable wit and panache during the dark days of World War II, while he was living in occupied Paris. In this particularly audacious example, he turned a bronze gas-stove burner and pipe on end to form a fertility figure and, in a very Duchampian touch, titled it The Venus of Gas. Nearby is his better-known Bull’s Head, a bronze that began life as an assemblage of a bicycle seat and handlebars.

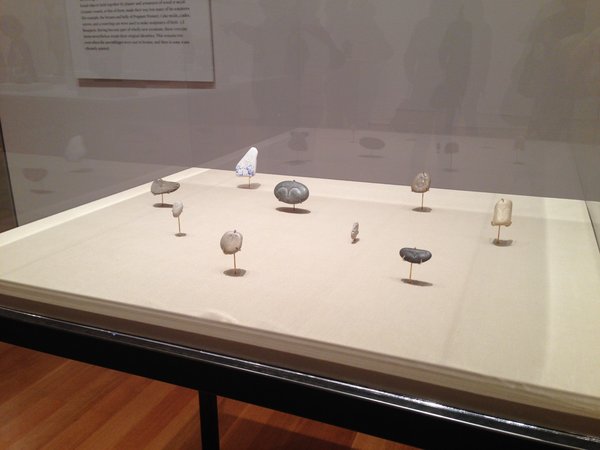

ENGRAVED PEBBLES, BONE FRAGMENTS AND CERAMIC FRAGMENTS

1946

All from a private collection

After the war, Picasso spent a restorative period along the Côte d’Azur. There, he strolled the beaches picking up pebbles, bones, and any other bits of detritus that caught his fancy. He then modified them with shallow carvings of human and animal faces, sometimes working right on the beach with scissors or whatever else was at hand. These small curiosities might be seen as collaborations with nature, as Picasso himself implied: “The sea shapes them so nicely, gives them such pure, such complete, forms, that we have only to add a finishing touch to make them into works of art.”

LITTLE HORSE

1961

Private collection

Relatively late in his life, Picasso embraced sheet metal as a sculptural material. He had used it before, in a version of Guitar, but this time he engaged professional fabricators. Working with designers and sculptors from the Tritub furniture workshop, he made designs of cut and folded paper that were then translated into metal. Some of these works merely flirted with functionality, as in Chair, with its uncomfortable-looking tilted seat. In the case of Little Horse, however, Picasso added wheels to the sculpture’s six pieces of metal tubing so that his grandson Bernard could take it for a ride. (In the catalog is a charming photo of the boy astride the horse.) Diminutive, familial, and unabashedly playful, Little Horse finds Picasso reinventing sculpture by cutting its heroic, historic, and monumental aspirations down to size.