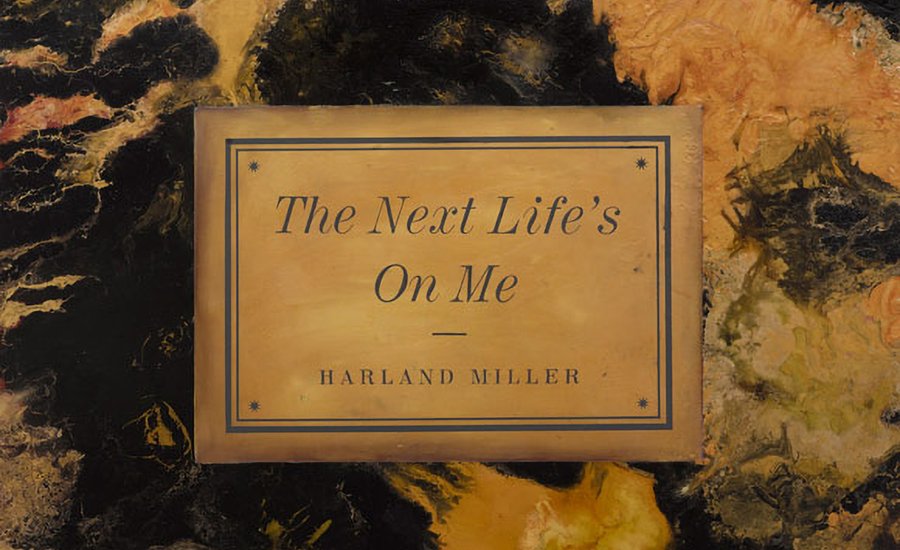

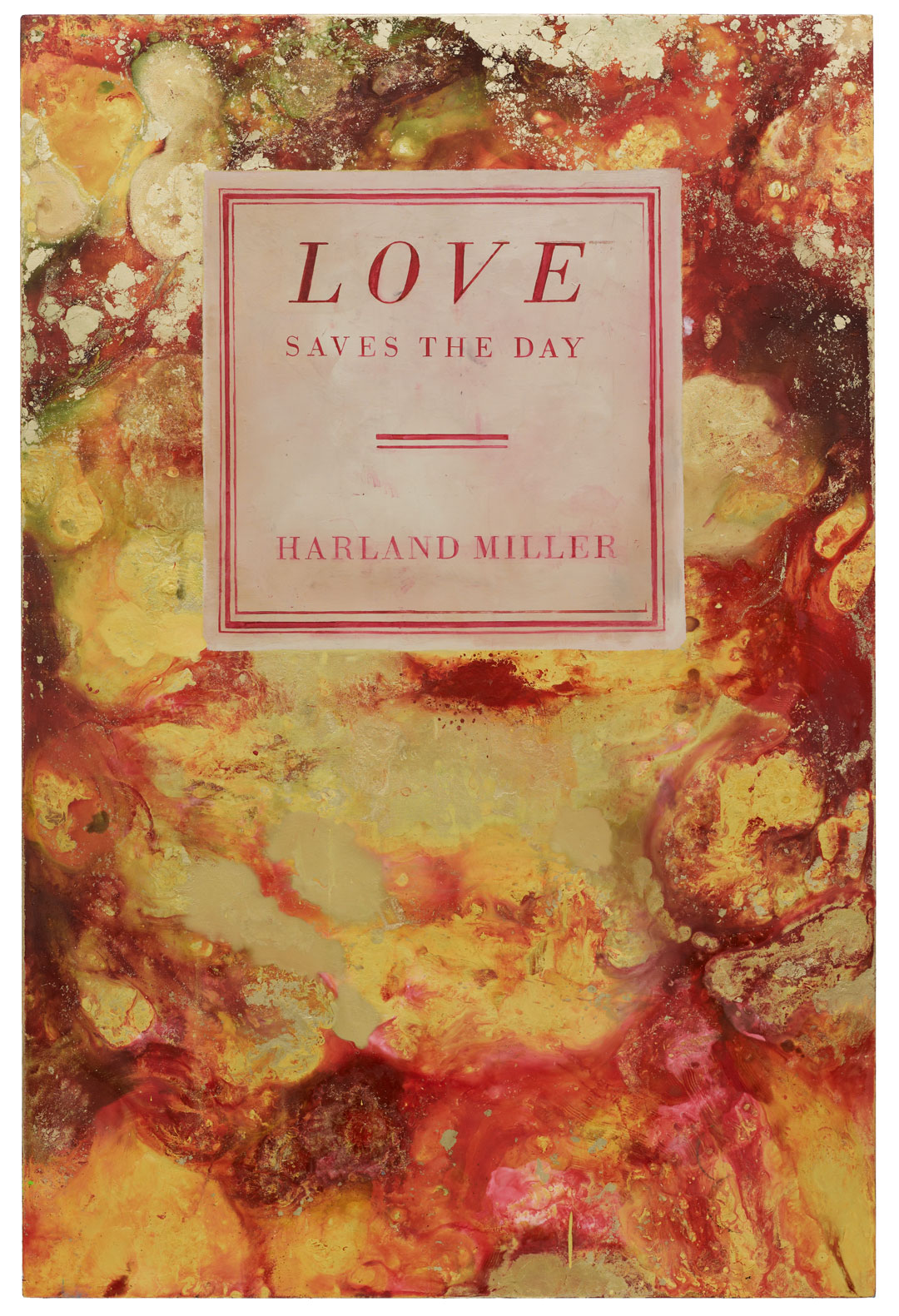

Harland Miller created his "Poets" series between 2012 and 2014. These pictures, as the name suggest, mimic the marbled paper covers used on old-fashioned Penguin poetry editions. Miller has said that he favored this mottled look not because it looked like any one volume of verse, but more because it had a “feminine and psychedelic” appeal.

Love Saves the Day

(2012) by Harland Miller, from the artist's "Poets" series. As reproduced in

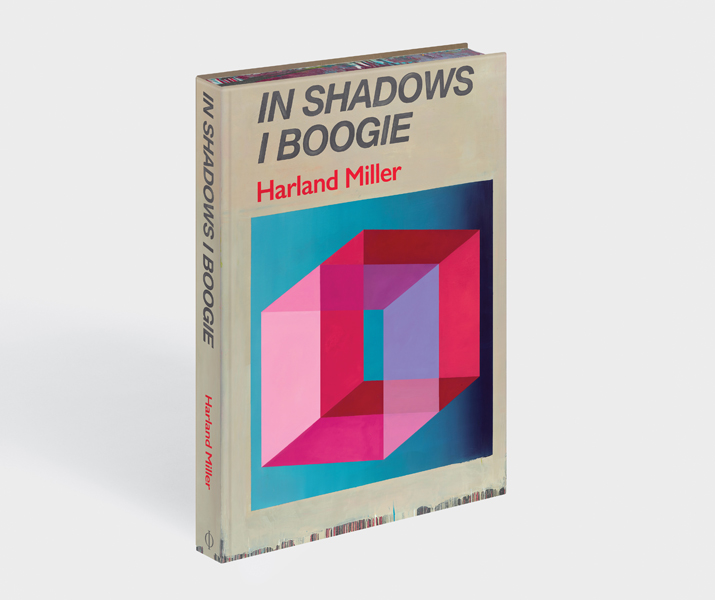

Harland Miller: In Shadows I Boogie

(Phaidon)

Love Saves the Day

(2012) by Harland Miller, from the artist's "Poets" series. As reproduced in

Harland Miller: In Shadows I Boogie

(Phaidon)

Unfortunately, in order to achieve this dreamy effect, which is actually quite easy to achieve on paper, Miller had to develop a remarkably tortuous technique. “To begin with, the canvas had to be flat on the floor so the paint could be poured on to it and, oh yeah, these weren’t traditional canvases, but metal frames supporting heavy wood panels,” he explains in his new book, Harland Miller: In Shadows I Boogie . “If I’d used normal canvas, the weight of the paint would just pool in the middle, like a puddle of dirty rain on a tarpaulin stretched over a skip.”

“To control the flow of the paint, you had to lift the whole thing up—tip it this way and that—the action resembling what the Russians call prisiadka, that up-and-down squat part of the Cossack dance,” the artist goes on. “Plus, because these were ‘one hit’ paintings, you had to keep going and going until they were finished, for as long as it took, as long as the day was… and I don’t mean a 9-to-5 day, I mean it could be 9-to-5… 5 AM—which is a long time to be doing prisiadka and inhaling a lot of thinners and paint fumes to boot.”

Those vapors and airborne specks were a little more harmful on this occasion, thanks to Miller’s chosen medium. “The paintings’ seams are created with metal-based pigments of copper, silver, and gold and at the end of the session, the air would be thick with these particles, like dust in sunlight, and I’d be covered in it too,” he goes on. “It turned out to be highly toxic and only to be used wearing overalls, whereas I was in shorts and smoking cigarettes, so sucking it in with nicotine, too. This led to a pretty severe case of heavy-metal poisoning, and then in turn to three months in an Austrian clinic.”

From the viewer’s perspective, the picture’s laborious, poisonous quality might make them a little more intriguing. However, Miller felt he needed to find a way to forget his ordeal. “When we first showed these works all together, I wanted to light them in an otherwise blacked-out room so that their physical form would disappear, be subsumed into weightlessness,” he reveals, “so looking at them wouldn’t just remind me of the effort it took to paint them.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

Laughter and After: Harland Miller's Use of Humor—by Martin Herbert

Decorator Kishani Perera on Creating a Balanced Home for Art and Everyday Life