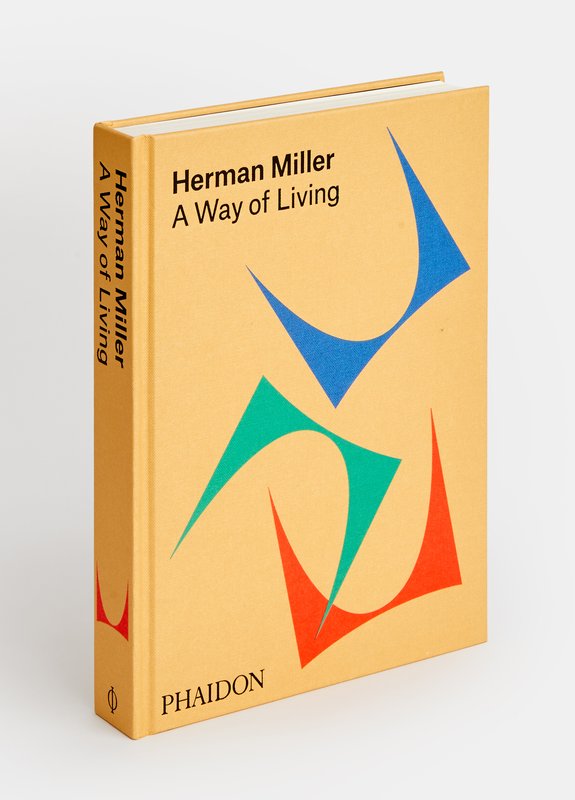

The following is excerpted from Phaidon's recently published book Herman Miller: A Way of Living , edited by Amy Auscherman, Sam Grawe, and Leon Ransmeier.

To some lucky grandchildren, Herman Miller is the name on the label underneath the stylish and comfortable lounge chair handed down by their grandparents. But in the early twentieth century, in the small town of Zeeland, Michigan, Herman Miller was a person.

Located on a flat wooded expanse tilting toward the shores of Lake Michigan, Zeeland was founded in the mid-nineteenth century by an organized church composed of God-fearing Dutch émigrés. The town developed from the same hardscrabble roots as many in the New World, but the no-nonsense, homogenous Zeelanders worked hard to maintain their Dutch customs and cultural traditions. Michigan’s bounty of old-growth forest was among their prime resources, and over time, they became proficient craftsmen and clockmakers. Loggers from around the state floated their trees along the coast of Lake Michigan up the Grand River as far as they could; burgeoning Grand Rapids, Zeeland’s largest neighboring city, became one of the nation’s leading producers of furniture.

In 1905 Herman Miller, along with Jacob A. Elenbaas and a group of local businessmen, raised the funds to convert a defunct canning plant into a factory to manufacture furniture. The Star Furniture Company, which Elenbaas managed, had little to distinguish it from some four thousand other manufacturers in the area turning out traditional designs in the Grand Rapids style. But they persisted and grew based on sales of “princess” dressers to Sears, Roebuck and Company. Dirk Jan (D.J.) De Pree, a young clerk who had been working at the company (by this time called Michigan Star) since he graduated form high school in 1909, married Miller’s daughter Nellie on May 5, 1914. Although De Pree had once vowed never to work in an office, never to work in the furniture trade, and never to live out his days in Zeeland, by 1919, when he took over as the general manager of Michigan Star, in addition to his duties managing the Herman Miller Clock Company (and with two kids at home and the Great War raging overseas), he suspected he was probably in the business for life.

Herman Miller: A Way of Living

is available on Artspace for $89

Herman Miller: A Way of Living

is available on Artspace for $89

By 1923 Elenbaas wanted to pursue oil prospecting in Texas and sought to divest his controlling stake in Michigan Star. Miller suggested to his son-in-law that they make the investment together, and shortly thereafter, at the insistence of Miller, De Pree was appointed president of the new company. His first act was to change the name. “I had always felt that Michigan Star was a corny name,” De Pree later recalled. “Therefore, we changed the name to Herman Miller Furniture Company. Mr. Miller, while not widely known in the furniture industry, where he was known he was recognized as a man of quality and integrity.” Early promotional materials made bold attempts to personify the enterprise. “Herman Miller’s life has been entirely devoted to the creating of fine furniture,” read one brochure. “The furniture built under his management has a goodness and a beauty that recognizes no peer,” state another. However, Herman Miller’s true role in the company remained one of arm’s-length mentorship and financial support. Although he never worked for the company that adopted his name, he was the first of many influential contributors to the unlikely progress of an organization that would transcend its humble origins to become one of the most celebrated businesses of the twentieth century.

The story of the furniture business that D.J. De Pree and his sons Hugh and Max helmed through the mid-1980s, and that continues to this day, is as improbable as it is inspiring. Much of the fact that there is still a story to tell can be traced back to D.J. and the unusual spirit that guided his approach to business. Unlikely though it may seem, it was his devout Christianity and rapacious appetite for the teachings of the Bible that led him to implement wholly progressive positions that would take Herman Miller in unexpected, but ultimately fruitful, new directions.

In 1927, when the company’s millwright died suddenly, D.J. went to pay his respects to the grieving widow. She showed him the exquisite handicrafts her husband had made for his home and the poetry he had written. After the funeral, while walking the short distance between the church and his home, De Pree acknowledged that his view of this man had been framed entirely through his position in the factory. He quickly came to understand that each of us are, in our own way, “extraordinary,” and adopted a different view of work and workers. D.J.’s epiphany led him to implement shorter hours, to move away from the piecework system that served neither the company nor all employees, and eventually to a form of participative management called the Scanlon Plan. “A business is rightly judged by its product and service,” he later wrote, “but it must also face scrutiny and judgment as to its humanity.” To this day, the company practices what Max referred to as “servant leadership”—the belief that leaders achieve their best when they discover what their followers need and help them reach their greatest potential.

During the Great Depression in 1930, it was clear to J.J. that the business was headed toward bankruptcy within a year. One afternoon, at the summer furniture market in Grand Rapid’s Keeler Building, a man by the name of Gilbert Rohde came into the showroom trying to drum up interest in his modern designs. “I didn’t grasp what he was driving at,” D.J. recalled, “but I was like a drowning man grasping at straws and wondering if the Lord was in his visit.” The company couldn’t afford to pay the designer’s fee, but instead Rohde proposed a three percent royalty arrangement based on future sales. After months at the drawing board, Rohde offered Herman Miller two bedroom groups that to De Pree looked like utterly plain boxes. Rohde insisted they be produced exactly as they were drawn, and eventually, it dawned on D.J. “that this man knew things that I didn’t know… I began to see that function and simplicity were truth in design.” The association with Rohde set Herman Miller headlong on the path toward problem-solving modern design. Perhaps even more importantly, it established a crucial role for outside designers at the heart of the company—a position that Rohde’s successor, George Nelson, expanded upon definitively and used to catapult Herman Miller onto the global stage. Of Nelson, Hugh De Pree once wrote, “Perhaps never has a designer so changed the philosophy, attitudes, and direction of a company… He became involved in the whole business… And in [a] very short time, he designed a ‘design driven’ organization.”

Herman Miller has grown exponentially and undertaken radical shifts and turns in its direction—from the needs of people in residences to institutions to workplaces to medical facilities and back again—but the spirit of Belson’s design-driven organization is very much in place today. In his introduction to the 1948 catalog, the designer codified the company’s approach, not only making it clear to customers that something different was afoot, but also providing a philosophy that informed the contributions of his contemporaries, such as Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, and Isamu Noguchi, and has continued to resonate with future generations of Herman Miller designers and employees. The belief that well-designed products help solve problems and improve living conditions remains at the core of the company’s mission.

Fundamentally, a company that puts design at the center of its business is placing a bet on the future. For Herman Miller, that bet hasn’t always been a winner, but as Max De Pree once wrote, “In the end, it is important to remember that we cannot become what we need to be by remaining what we are.” While D.J. may have believed “that each of these points of change, directions, and decisions, were very clearly Prrovidentially directed,” over time the company built networks and capabilities—like the Technical Center and Research Division—to help guide its course and shoulder the risks. Even so, the world does not know it is ready for something like the Aeron Chair until there’s an Aeron Chair. The values D.J. an his sons passed along have helped to foment an atmosphere in which that kind of real innovation is still possible. In the end, those values return to a simple concept, one that D.J. learned early in his career from Gilbert Rohde: “The other thing that Gilbert Rohde said to me one day, he said, ‘You think the interesting thing in the house in period design—the interesting thing is the people who live there.’ This was almost an earth-shaking statement to me. I’d never thought about that. And later on he supplemented it. He said, ‘You’re not just making furniture anymore; you’re making a way of living.’”

Here are five Herman Miller innovations that continue to infuence design today:

Biomorphic Form

No. 4187 and No. 4186 Paldao Group tables designed by Gilbert Rohde, 1941. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

No. 4187 and No. 4186 Paldao Group tables designed by Gilbert Rohde, 1941. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

In his 1936 introduction to the Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog Cubism and Abstract Art , Alfred H. Barr, Jr., described two strains of abstract art: one that is “intellectual, structural, architectonic, geometrical, rectilinear, and classical in its austerity and dependence upon logic and calculation,” and another that is “intuitional and emotional,” “organic,” “curvilinear,” “decorative,” “and romantic rather than classical in its exaltation of the mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational.” Borrowing from the art world, designers began to incorporate the new formal language of bioorphism into architecture and objects. It features heavily in Gilbert Rohde’s design for his own offices and an installation for the Conteporary American Industrial Art exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His “ectoplastic” tables and desks for Herman Miller were the first biomorphic furniture designs to be manufactured in the United States.

Evolving Case Goods

No. 5733 Thin Edge chest desk with No. 5890 Pretzel chair designed by George Nelson, 1958. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

Two lines introduced by Herman Miller in the early 1950s illustrate George Nelson’s continued evolution of practical and elegant designs for modern storage. The economical Steel Frame group reduced the cabinet structure to a minimalist skeleton that supported a laminate top and wood drawers offered in a vriety of colors. More luxurious but still highly versatile, the Rosewood Group offered modular storage with refined lines and porcelain hardware. Miniature chests adopted the design language at a diminutive scale. In 1958 the line was renamed Thin Edge to accommodate a choice of hardwood veneers and broader range of options.

The Marshmallow Sofa

The Marshmallow Sofa: promotional photograph featuring George Nelson and Associates receptionist Hilda Longinotti, 1956. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

The Marshmallow Sofa: promotional photograph featuring George Nelson and Associates receptionist Hilda Longinotti, 1956. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

Originally devised by staff designer Irving Harper to make use of a prospective technology that promised self-skinning, injection-molded cushions, the 5670, or “Marshmallow,” sofa atomized the design of the bulky, standard sofa to a set of disks independently attached to a tubular steel frame. When the new manufacturing process proved unworkable, Herman Miller decided to produce the sofa anyway—at great expense. With hand-upholstered, plywood-backed “marshmallows,” few sofas sold; however, the product almost immediately became an icon of mid-century design.

The Aluminum Group

Charles and Ray Eames: Aluminum Group; promotional photograph displaying expanded Aluminum Group seating range, c. 1971. Picture credit: courtesy and copyright © Herman Miller Archives

When Alexander Girard noted the dearth of outdoor seating options for the verandas of the Eero Saarinen-designed Miller House in Columbus, Indiana, he requested that the Eameses design a new chair to meet his clients’ needs. Within a year, the Indoor-Outdoor Group—featuring a waterproof polyester saran textile held in tension between two aluminum Ls—was in production at Herman Miller. With the addition of heat-sealed Naugahyde or fabric pads, the versatile design found a multitude of indoor applications and the line was soon recast as the Aluminum Group. By the early 70s, it had expanded to include dining and lounge chairs and, with the addition of casters, seating for the office.

The Eames 670 and 671

The Eames 670 chair and 671 ottoman within the Eames House, photographed by Charles and Ray Eames, 1956. Picture credit: © Eames Office LLC/Library of Congress

The design of a chair for reclining and relaxing, which began with an asymmetrical “lounding shape” conceived for the Organic Design competition in 1940, culminated in 1956 with the introduction of the Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman. Incorporating elements of earlier designs—molded plywood shells, rubberized shock-mount connections, an aluminum base adapted from the Molded Plastic Chair—the set strove to provide an update to the classic English club chair and provide “the warm, receptive look of a first-baseman’s glove.” A note from Ray to Charles dates August 1955 describes refining touches made by Alexander Girard, Don Albinson, and Ray herself, noting that they “kept testing and going to sleep in it!”

RELATED ARTICLES:

8 Young Contemporary Artists Making "Furniture"

Interior Designer Carolina Irving on Camp, Authenticity, the Problem with Good Taste

Location, Location, Location: Artist/Architect/Designer Jorge Pardo on Why Context Is King