Since the Berlin Biennale opened at the beginning of last month, a few seismic things have happened. A foiled military coup just took place in Turkey, for starters, while the Brexit put the future of the E.U. in question, a police assassin brought racial tensions in the United States to a height unseen in a generation, and ISIS claimed a torrent of lethal terrorist attacks on a Nice boulevard, in an Orlando gay club, in an Istanbul airport, and across Bangladesh, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia. In the meantime, Amazon celebrated its own holiday (Prime Day), augmented reality sent millions of Pokémon fans into the streets in search of fictional animals, and Facebook changed the way the world gets the news with a tweak of its algorithm. By the way, a reality TV star is running for the U.S. presidency on a surging tide of recriminatory hate.

If there’s one certainty in this jittering era of near-continual flux, chaos, and disruption, it’s that our lived experience is heading in a downright surreal, worrisome direction. Such is the climate behind the Biennale, which puts its own twist on the current moment’s existential fatalism: “Tomorrow is obvious. Today is unfathomable.” Organized in five piquant locations around the city by DIS, the millennial quartet of Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro that W magazine called “the definite Post-Internet art collective,” the extensive exhibition sets out to capture the 2016 vibe through the work of artists who exaggerate or otherwise intensify current concerns—“The Future in Drag” is the title of the show, and indeed there’s a lot of dramatic posturing taking place. But it’s best approached as a kind of CES for au-currant ideas, and artistic attitudes.

One thing that’s immediately clear is that DIS’s Berlin Biennale is not Okwui Enwezor’s oppositional Venice Biennale, which presented a critique of the art world’s Western-centric solipsism in the age of globalization. If anything, it’s the opposite—an accelerationist extravaganza that frames the world an increasingly messy, scary place where the way forward can be found in an amalgam of liberal Western attitudes, new technology, global perspective, and marketing savvy.

In fact, as the world at large experiences a crunching backlash to the principles of neoliberal capitalism, the biennial can be seen to provide lessons on how individuals (and artists) can survive and even thrive in the unsettled, increasingly sci-fi arena of the future. In the catalogue, the organizers declare that “the artists and collaborators that we have mobilized are not fatigued but energized by this uncertainty.” It’s a bit like the Hunter S. Thompson line: “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” And, to quote George W. Bush: “Bring it on."

Here are a number of takeaways from the 9th Berlin Biennale on what Post-Internet success entails.

Business Is the Best Art

An in-exhibition Biennale ad by Roe Ethridge in collaboration with Babak Radboy and Chris Kraus

An in-exhibition Biennale ad by Roe Ethridge in collaboration with Babak Radboy and Chris Kraus

That immortal Warhol dictum seems to have been fully embraced and given an update by DIS, which became famous for approaching art as a kind of “brand voice” that they apply across their online magazine, photo service, and extensive event collaborations with corporate sponsors like Red Bull. They also make discrete artworks that celebrate bizarre varieties of product fetishism—like the lie-down shower that was the centerpiece of the last New Museum Triennial—and new modes of identity that rely on stock images, body modification, and Benetton-like multiraciality, but the art is really more or less a visual advertorial for the core DIS brand, which presents itself as a successful, youthful, next-gen global corporation. A lot of their art is set in generic workplaces. It’s a through-the-looking-glass form of what you might call Yuppie Conceptualism. It’s also deeply, deeply ironic.

For the Berlin Biennial, they underscored this businesslike approach by setting parts of the exhibition at the European School of Management and Technology—which the catalogue describes as “a private business school located in the former building of the GDR’s State Council” that trains “future executives”—and a former telecommunications bunker that has been refashioned as the private Feuerle Collection. The tech associations are key to DIS, because whereas Warhol made art by essentially painting ads for Campbell’s Soup, Brillo, and celebrity figures, the collective realizes that the Internet (and social media) has made branding an important part of everyone’s lives, not just corporations, politicians, and stars.

The theme continues across the other locations, such as at KW Berlin, where DIS’s own art contribution consists of video infomercials playing over the ticket counter that promise a utopian future while showing a wide variety of characters furiously manipulating transparent Plexi “smartphones.” In the staircase, meanwhile, is a series of wheat-pasted advertisements that show edgy young women looking out from normative, stock-image tableaux alongside slogans like “I miss the conspiracy” and “Stop looking at me like I’m the future”; orchestrated by Berlin Biennale creative director Babak Radboy in collaboration with the author Chris Kraus, they were shot by the artist Roe Ethridge. The effect is to make building feel like a Verizon store combined with a Nike flagship mixed with VFiles outlet.

A scene from Amalia Ullman's Privilege

A scene from Amalia Ullman's Privilege

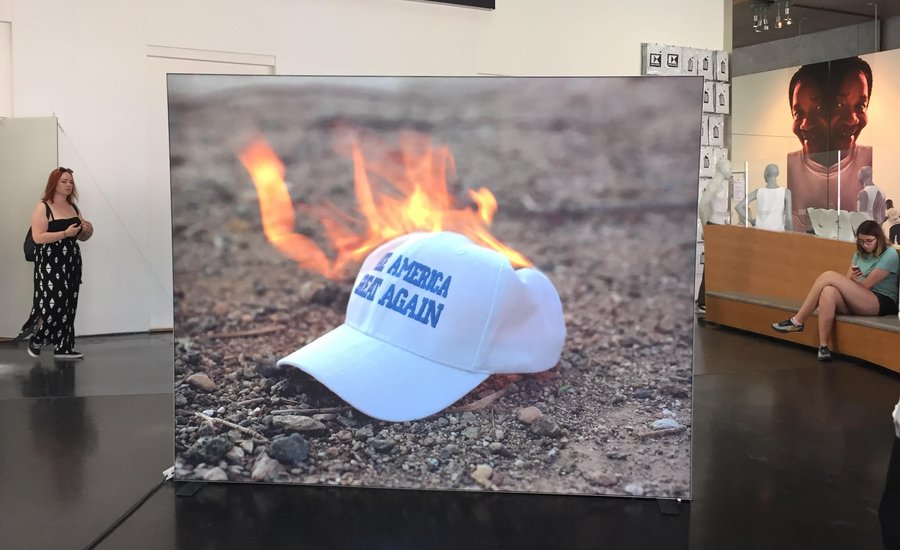

On the first floor, Amalia Ullman plays with brands in Instagram videos where she fakes a pregnancy and surrounds herself with high-status objects like Gucci loafers, Maclaren strollers, and Baby Björns (while also hanging out with a pigeon and donning a clown nose)—it’s called “Privilege,” as a commentary on how making this kind of critique-y-esque art is entirely due to her position as a well-off white artist who doesn’t have to worry about things like working three jobs to feed her family. Outside, a giant cut-out by Colombia’s Juan Sebastián Peláez of a bikini-clad Rihanna with her head grotesquely embedded in her chest (like the myths of New World savages perpetuated by 16th-century explorers) presents a catchy riff on a celebrity who has monetized every aspect of her life, from her 41.3 million-follower Instagram account to her perfume line.

Juan Sebastián Peláez

Juan Sebastián Peláez

Meanwhile, things get literal at the biennial’s Akademie der Künste venue, where the artist who goes by Debora Delmar Corp. runs a green-juice health bar where visitors can buy a drink and enjoy it in a lounge setting whose “upcycled” features are meant to echo the way Western companies import the juice’s ingredients from developing countries and dramatically increase the price. Near the bar is the exhibition’s gift store, which is actually a contribution from the edgy Liberian-born fashion designer/artist Telfar Clemens, offering mutated Hanes-style ribbed tank tops (€90 a pop, since abnormal, small-batch renditions of ultra-normal, mass-produced clothes don’t come cheap) that are displayed on grinning mannequin portraits of Clemens (made in collaboration with the artist Frank Benson) and also shown in ads worn by ordinary-looking black non-models; he also made souvenir t-shirts and totes for the biennial, plus uniforms for the security guards. (The chic fashion designer Hood by Air is also listed as a participant in the show, but after a thorough tour it was not immediately apparent where or how.)

A TELFAR mannequin

A TELFAR mannequin

Taken together, the artworks suggest a funny kind of business/branding-as-aesthetic, cut with enough air quotes to make it cool. Difference, like race, gender, or sexuality, is no longer a hurdle—it’s a differentiator. In the Biennale, selling out appears as the new keeping it real.

Corporations Are More Important Than Countries

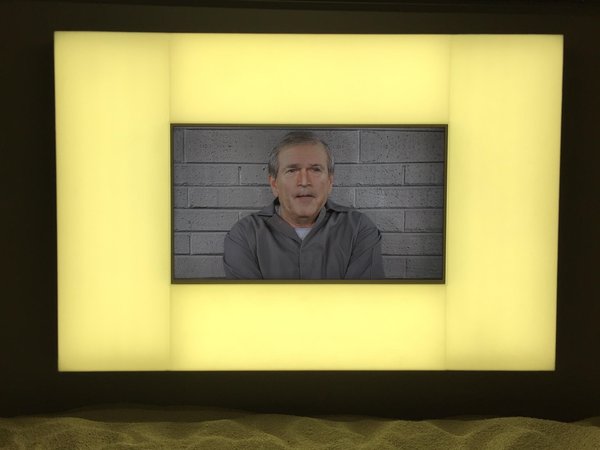

Josh Kline's Crying Games

Josh Kline's Crying Games

Around the time of the Brexit, the artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah remarked that the Leave voters were mistaken to view the European bureaucrats in Brussels as the oppressing power—when really they should have been looking at global companies like BP and Apple. “I don’t see how Parliament will improve our dealings with these huge corporations that run most of the world,” he said. “In fact, there’s every argument to say it should make things worse, because our ability to negotiate with these behemoths would diminish.”

In the Biennale, several artists have taken this position—that corporations are more estimable than countries—even further. Josh Kline’s powerful 2015 video Crying Games sets the tone, presenting the U.S. as reputationally bankrupt in a video that shows a succession of fairly realistic CGI renderings of George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld, and other Iraq War leaders in prison jumpsuits in a Gitmo-like setting, apologizing at pitiful length. (“Oh god, what have I done? All those people! I’m a monster. I’m so sorry. All those people,” says Bush.) The piece is installed in a claustrophobic concrete room filled with kitty litter.

Corporations, meanwhile, are often shown as inspiring, even utopian. A spellbinding video by the British artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas, New Eelam, begins by recounting the story of the Sri Lankan breakaway nationalist insurgency Tamil Eelam (know for their Tamil Tigers militants), describing it as a “free secular socialist state” that sought to liberate itself before being brutally crushed by the Sri Lankan government in 2009; it then segues into a story about Jeff Bezos’s founding of Amazon and how the company established a global business that successfully eluded national boundaries to cater to an audience worldwide.

“What if technology could create a more liquid form of citizenship that exists outside of boarders?” the narrator muses. The tenor then abruptly changes, from history lesson… to a commercial for an online home-sharing company. “We think this can be possible when essentials like housing are owned collectively” through “New Eelam’s flexible housing subscription” with “global gym, co-working, and car-sharing systems from our partners” leading to “a new economy—one where it’s possible to have more together than we ever could alone.” It’s a Marxist revolution in the form of AirBNB.

The installation by åyr

The installation by åyr

The video, it should be said, is given a rebutting counterpoint by London-based collective åyr, known as AIRBNB Pavilion before that company sent a cease-and-desist letter, who take a particularly jaundiced view of home-sharing. Seeing it as a dehumanizing elimination of public/private ownership, they present a structure based on the Berlin Wall that is covered with photos of anonymous, chic apartments denuded of all personal traces, with oppressively tiny prison-like sleeping nooks carved into the wall.

Another optimistic piece—again borrowing from the canned uplift of tech-company commercials—comes from Simon Denny and Linda Kantchev. Installed at the European School of Management and Technology, a video showing country roads at night and other comforting imagery mixed with technical illustrations of countless linked nodes is narrated by a reassuring older male voice (like an insurance ad) that intones: “Imagine a world where trust is guaranteed. A world without boarders. A world in which each and every one of us takes part in the whole. This world is already here, embedded in the blockchain.”

An installation by Simon Denny and Linda Kantchev

An installation by Simon Denny and Linda Kantchev

Presenting the blockchain, the distributed database at the heart of Bitcoin, as a transformative social contract that transcends national limits to (again) create an egalitarian, socialist global community, the video is accompanied by a series of trade-show display booths celebrating such e-currency heroes as 21 Inc. venture capitalist Balaji Srinivasan (avatar or a “tech-led, post-national free market”) and Ethereum’s Vitalik Butarin (proponent of an “open, decentralized Internet and distributed governance infrastructure”).

This kind of technological utopianism finds its most baroque expression in Alexa Karolinski and Ingo Niermann’s Army of Love, which presents yet another video ad, this time promoting an Uber-like online community devoted to offering “encompassing sensual love—care, desire, sex, and respect—to all those who need it.” Showing various volunteers tenderly handling naked love-recipients as they float in a pool, the ad ends with a heart logo and the line, “Help the Lonely! Join the Army of Love. www.armyoflove.net.” An accompanying text spells out practical tips for members: “We learn from sex workers to desire the other by making her or him desire us and so satisfying our self-love. If we can’t pull it off on our own, we may also rely on the assistance of substances such as MDMA (more attraction), oxytocin (more attachment), and Viagra (more erection).”

In this world, tech-enabled socialism even offers free love, and companies represent a new kind of economic miracle.

Prepare for the Worst

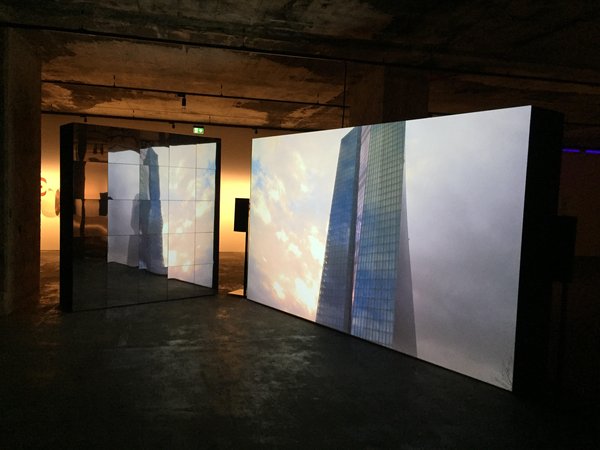

Korpys/Löffler's video

Korpys/Löffler's video

Visitors to the Biennale should enjoy the positivity when they find it, because in other works dotting the biennial the outlook ranges from dim to Vantablack-dark.

First, the dim. Beautifully installed in a mirrored enclosure in the Feuerle Collection, the German filmmaking duo Korpys/Löffler’s multichannel 2016 video Transparenz, Kommunikation, Effizienz, Stabilität presents footage of the European Central Bank Building in Frankfurt am Main—a gleaming glass-and-steel tower designed in by Coop Himmelb(l)au, who intended it as a symbol of financial transparency—as a gusty storm rages outside.

The camera roams the empty lobby while the soundtrack plays keyboard clicks and the occasional corporate audio mnemonic (like the “Intel Inside” jingle) that sonically suggests, through its pleasant swelling synth, that everything is under control and getting better by the day. This impression is then vividly undercut on another screen by Super-8 footage of the Blockupy protests that took place outside the building last year, with masses chanting “End ECB dictatorship!” and setting fires in the streets as riot police descend—again to the sound of the upbeat corporate jingle. The ideological promise of the building’s architecture, of accountability and openness, is revealed to be a mask of oppression.

A sculpture by Anna Uddenberg

A sculpture by Anna Uddenberg

Elsewhere, at the Akademie der Künste, the Swedish artist Anna Uddenberg has sculptures that seem to encompass the way that consumers (i.e. people) are shaped by the marketing-saturated, exhibitionism-hungry, globalized media climate—into freakish amalgams of half-naked, contorted female bodies in athletic wear fused with carry-on suitcases, in one case taking a photo of her upturned rear with a selfie-stick. Playing in a conference room, meanwhile, a video by Los Angeles-born artist Will Benedict shows a combat-boot-clad alien creature (the “other” personified) appearing on the “Charlie Rose Show” and mouthing the anarchistic lyrics of Wolf Eyes’s song “T.O.D.D.,” speaking of a desire to bring cataclysmic riots to the streets to avenge systemic injustices. (“I burn my dreams just to stay warm,” he says/sings.)

Anne de Vries’s Critical Mass: Pure Immancence

Anne de Vries’s Critical Mass: Pure Immancence

It gets spookier in Anne de Vries’s Critical Mass: Pure Immancence (2015), a video and sculptural installation of a “hardstyle” EDM concert where a huge crowd gathers in an outdoor arena, smartphones glowing in their upraised hands, as a calm robotic voice welcomes them to “the omnisphere” where “only one rule applies” as they seek the “ultimate flow.” The voice then declares that “the time has come” to eliminate “redundancies” as a giant head shoots entrancing light beams from its eyes. It’s a terrifying vision of a post-Singularity future—but it’s also a pretty literal view of what actually happens at EDM concerts today.

Stills from videos by Cécile B. Evans

Stills from videos by Cécile B. Evans

Then there’s arguably the Biennale’s keynote installation, the trio of videos by the young Belgian-American future-shock specialist Cécile B. Evans that are projected in a large darkened room where a platform brings viewers to the screen across a pool of black water. What plays are paranoid fantasies of an apocalyptic near future where, as different narrators reveal, a sentient “system” holds sway, human-like creatures are grown in pods (“Oh god I thought they were children,” a voice says; “It's the hands that give away it's a system, not the face,” another responds), the landscape is a desert wasteland (“There was a worldwide earthquake and we had to rebuild the Internet from the archives of a defunct company”), mass shootings are pervasive on the news, schools are “banned,” new prejudices are born (“Everyone keeps telling me it's not a legitimate disease”), and apathy pervades (“People live forever through cell reviving” but “no one could say anymore what is great or what is good”).

What’s notable is that the most pessimistic of these takes don’t imply that any kind of action should be taken to avert such an outcome. Conservativism is not cool; being ahead of the curve is. As the Biennale curators write in the catalogue, “The future feels like the past: familiar, predictable, immutable.”

Embrace the Chaos

Sculptures by Guan Xiao

Sculptures by Guan Xiao

Instead, the takeaway of the Biennale seems to be that “the way out is in,” as the Zen expression goes—to find ways to latch onto the miasma of the implacable change and find ways to succeed within it. This is the case with the sculptures by China’s Guan Xiao of animals and plants growing melding with the tires, exhaust pipes, and hubcaps of environment-destroying cars. We should follow their example, like so many hermit crabs accommodating themselves in garbage.

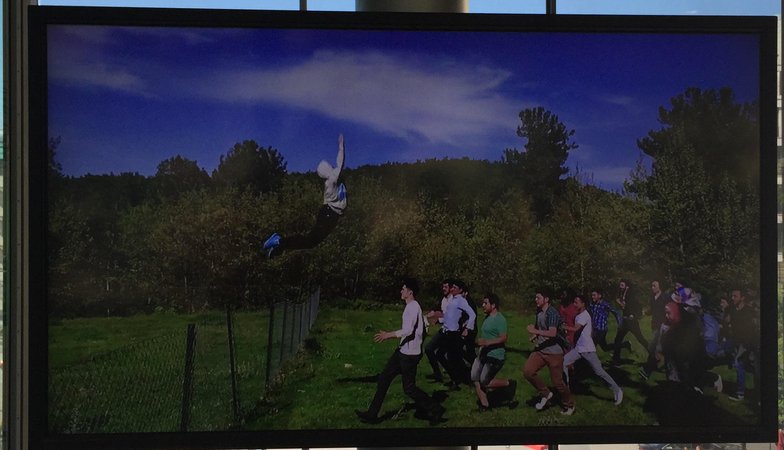

A view of Halil Altindere's Homeland

A view of Halil Altindere's Homeland

If there’s a migrant uprising at the border, in other words, we should lead it, as in the case of the great Turkish artist Halil Altindere’s Homeland (2016), where the Syrian conscious-rapping protagonist Mohammad Abu Hajar rallies a group of evacuees into Europe by doing backflips over border fences and spray-painting security cameras via drones. (At the end, Hajar, safely at Berlin's Tegel airport, addresses European opponents of immigration to say that he has no intention of staying permanently and taking their jobs, and fervently desires to return home.)

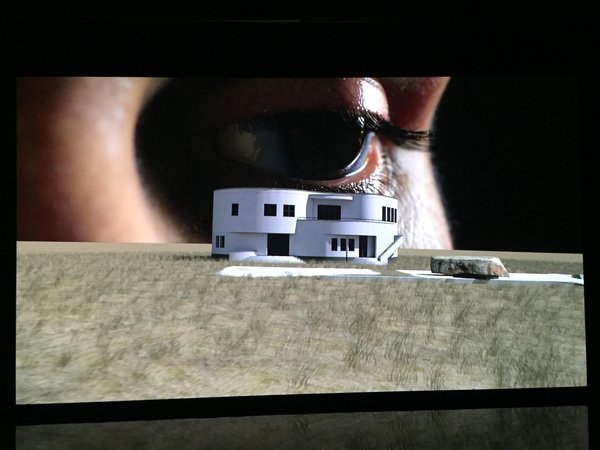

Hito Steyerl's ExtraSpaceCraft

Hito Steyerl's ExtraSpaceCraft

Drones, those emblems of technology outpacing morality, also play a central part in Hito Steyerl’s transporting new “docufictional” video ExtraSpaceCraft that takes the viewer to the former National Observatory of Iraq that is not an international astronomical hub, from which a Kurdish drone pilot sends his whirring machine to capture images of the surrounding landscape (there “are only a handful of drones” in the region, we learn, and “ISIS uses one for PR.”)

The video then shows Steyerl and others wearing NASA spacesuits and white Nike high-tops while the artist says that, while space missions are dwindling, “Now space travel happens on Earth—we call it ‘Extra Space Craft.’” Soon it segues into a sequence of a drone in flight, with the narrator shifting to say, “I am the drone” and revealing that it was a weaponized military robot that went “autonomous” and became friends with everyone, including a sheep, which accompanies it on its adventures.

The drone, in the video, becomes a metaphor for freedom, for the ability to make choices. We must become the drone, too. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em