On May 1st 2016, the elephants of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus gave the final performance of their careers, running through their paces in Providence, Rhode Island, one last time before being shipped off to a breeding and research facility in Florida. The move was heralded by many commentators as a step forward in the fight against abuses of animals in the entertainment industry.

Four days later, the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan premiered his piece Warning! Enter at Your Own Risk. Do Not Touch, Do Not Feed, No Smoking, No Photographs, No Dogs, Thank You at Frieze New York, a restaging of his 1994 piece of the same name that consisted of a live donkey standing underneath an ornate chandelier.

At first glance, there’s a wide gulf between the globe-schlepping, dancing pachyderms—some of the most intelligent and emotionally complex animals on earth—and the donkey, Sir Gabriel by name, whose act mostly consisted of munching hay and being gawked at by wrinkle-nosed art enthusiasts. But both performances zero in on trends in their respective cultures: a growing distaste for animal acts as popular entertainment on one hand, and, on the other, the massively increasing popularity of animals in contemporary art.

The Ringling Bros. elephants

The Ringling Bros. elephants

You don’t have to look hard to find recent indicators of the former in American popular culture. In March, SeaWorld announced that they would stop breeding orca whales in an effort to placate their increasingly vocal opponents and regain some of the visitors lost in the wake of Blackfish, the 2013 documentary detailing what can rightly be called the horrors of captivity for the sea mammals. There are now many laws on the books against animal abuse, and events like dogfighting and horseracing have been made illegal or otherwise rendered unpopular as the ethics around the use of animals for human hijinks continues to shift. While we’re hardly turning into a nation of vegans, there is a widespread and growing awareness of animals as thinking, feeling entities with some kind of claim on their own lives.

In the art world, however, things are a little different. Live animals in art are nothing new—famous works like Joseph Beuys’sI Like America and America Likes Me, featuring a wild coyote, and Jannis Kounellis’s recently restaged Arte Povera classic Untitled (12 Horses) dot 20th-century art history. But the past few years have seen a marked uptick in the number of artworks featuring actors from around the animal kingdom.

Bjarne Melgaard employed baby tigers in a 2012 Ramiken Crucible show, stirring controversy; Darren Bader positioned shelter cats as sculptures in his PS1 solo exhibition of the same year; there was Cai Guo-Qiang’s decision to mound iPads on live tortoises as part of a 2014 show at the Aspen Art Museum. French art superstar Pierre Huyghe is conducting an ongoing exploration of the aesthetic qualities of ocean crustaceans, bees, dogs, and more.

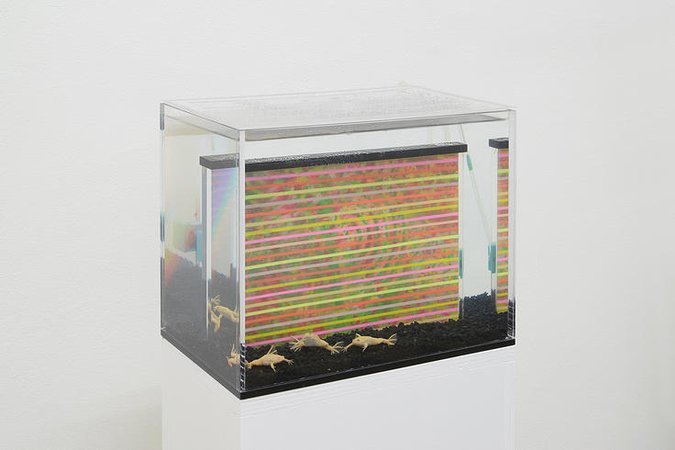

In the pasy year alone, we've seen fish, frogs, leeches, and scorpions incorporated into works by rising art fair star Max Hooper Schneider, performances by Hayley Aviva Silverman and Anne Imhof at MoMA PS1 presenting (respectively) speaker-wearing dogs and massive rabbits, and a gala featuring costumed chickens by Laura Lima as part of Performa 15. Just this month, Duke Riley premiered his latest pigeon piece with Creative Time in New York (consisting of hundreds of birds with LED lights attached to their ankles flying in formation over the Brooklyn Navy Yard at dusk), Brad Troemel closed a show at Feuer/Mesler that featured cockroaches consuming his homemade gingerbread houses, and Sir Gabriel had some company at Frieze in the form of hibernating snails used in sculptures by Nick Bastis at another booh.

Albino Clawed Frog-Tetra System by Max Hooper Schneider (photo by Alessandro Zamblanchi)

Albino Clawed Frog-Tetra System by Max Hooper Schneider (photo by Alessandro Zamblanchi)

The rationales given for employing live animals naturally vary from artist to artist, but a few commonalities can be teased out. Object Oriented Ontology, the hip-and-happening new school of philosophy theorizes that all objects and beings—from turtles and trees to neutrons and knapsacks—possess some form of consciousness that deserves respect. Artists like Huyghe and Hooper Schnider (a former assistant of his) make clear references to such ideas, and many others appear to be playing with them as well.

But in other cases, the use is practical: Animals are employed for what they do naturally to provide the action in the artwork, the performers of performance art. Examples include Brad Troemel’s gluttonous gingerbread-eating roaches at Feuer/Mesler, Duke Riley’s flocking pigeons, and Celeste Boursier-Mougenot’s musical finches, which hopped and flitted around the electric guitars placed in their aviary at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Is there perhaps a troubling flavor of “gimmick” to this trend? There’s no overlooking the simple fact that, in the overcrowded and sometimes carnivalesque art market we live in now, having a living, breathing, unpredictable being on display is sure to pull in some precious eyeballs. (Sales are another question entirely.)

The line between these artistic gestures and the more historically typical human-animal relationship—that of instrumental use as means to an end—tend to get a bit blurry. It’s one thing to imagine what a given animal thinks about or to appreciate its beauty, charm, or behavior; it’s another to place it in an art fair or gallery to perform those qualities for throngs of visitors. Some artists are even explicit in their conception of animals as tools or materials; Hooper Schneider calls his critters “faunal readymades,” and Bastis’s dealer at Frieze said, in no uncertain terms, that the decision to use live snails in his works is “less about their animalness, and more about what they do.” It seems some artists haven't moved far from Descartes’s infamous seventeenth-century conception of animals as "natural automata," or, in more contemporary parlance, "found robots."

Means to an end, indeed.

Duke Riley's pigeon performance. Photo by Kathy Willens

Duke Riley's pigeon performance. Photo by Kathy Willens

Few observers outside of animal rights groups would go so far as to claim the artworks mentioned here as examples of cruelty. Indeed, other than a small handful of deadly examples like Marco Evaristti’s 2003 goldfish-in-blenders piece Helena or the violent video works of Adel Abdessemed (most infamously featuring the slaughter of farm animals with sledgehammers and other brutal tools), most artists bend over backwards to prove to would-be critics that the creatures are being well taken care of. For instance, a wall text outside Cattelan’s Frieze piece asserted, “The animal in this exhibit has been humanely treated and not in danger at any time.” (Animals rights activists still protested.)

Still, in a time that’s seen widespread outcry against animals as entertainment, the reduction of living creatures to their use value sits strangely with the contemporary push towards recognizing the rights of animals.

This comes down to an issue of consent. If given a choice, would the creatures used in these artworks willingly participate? Some likely don’t mind, a few may enjoy it, and many would probably prefer not to, but the fact that we simply can’t know (and render the point moot by using the animals regardless) creates an ethical dilemma that the art world will have to come to terms with. Let’s be clear: in terms of moral crises in the 21st century, the use of animals in art hardly ranks. But given art’s self-asserted status as the vanguard of culture writ large, it’s interesting if not a bit anachronistic that artists are increasingly turning to them as tools in their work.

The question arises: why won’t artists leave animals alone?