Around this time last year, the art press picked up a quirky new story: a Yale photography M.F.A. named Sarah Meyohas had created her own cryptocurrency called Bitchcoin, with an exchange rate set at one Bitchcoin to 25 square inches of a Meyohas print. (As the value of her work changes over time, so too will the value of the coins.) In an art world that was grappling, often dismissively, with the shift toward art-as-investment, Meyohas’s take on the Bitcoin addressed the world of finance with unusual directness and a cooperative stance. It seemed to offer collectors a tool for using Meyohas's artworks as investments.

Sarah Meyohas

Sarah Meyohas

Her new show “Stock Performances” at 303 Gallery (running January 8th through the 30th) reverses the dynamic, using investments to generate artworks. For the next several weeks the gallery will become a stock exchange-cum-studio as Meyohas trades with an eye for aesthetics rather than profit, recording her results along the way with oil stick on canvas. At the same time, she’ll be creating a series of artists' books with a different kind of commodity, gold (the books feature paints made with gold nanoparticles, developed in conjunction with Dr. Erik Dreaden of MIT). And to top it off, the 24-year-old is also opening a new exhibition of works by Suzeanne McClelland and Brock Enright on January 22nd in her Upper East Side apartment gallery, Meyohas.

Artspace’sDylan Kerr met with Meyohas in 303’s cavernous gallery space where, surrounded by blank canvases that will eventually be marked with the records of her (and her stocks’) performance, they discussed how Meyohas went from a finance major at Wharton to a gallery show in Chelsea, the "lifestyle" of running an apartment gallery, and the potential legal ramifications of manipulating the stock market.

Let me preface this conversation by admitting that my knowledge of the stock market is more or less limited to what I’ve been able to glean from The Big Short and The Wolf of Wall Street. In layman's terms, what exactly are you doing here at 303?

I’m going to be trading stocks on the New York Stock Exchange over the course of the next few weeks. I won’t be looking at what the company is or what it does—I’m only looking at the line. My purpose in trading is to make the line that represents the stock's performance move in a way that I have impact on. This means I can’t trade Apple stock, for instance—there are too many participants there, and I would have to trade who knows how much to make an impact.

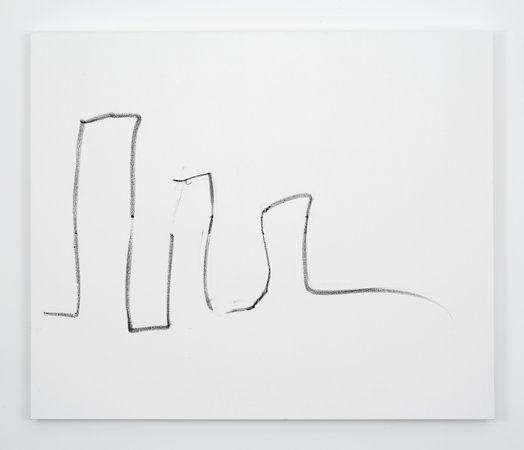

I’ll be trading smaller stocks, maybe a few with funny names—the stock I traded in the past was called Golden Enterprises [Meyohas created an early iteration of her "Stock Performance" in 2014/2015]. Once I have affected the stock’s valuation, I’ll go to one of these canvases and gesturally draw the line with black oil stick. The painting becomes a data visualization of the stock’s performance, where I’m enacting a kind of mirroring from the screen to the canvas.

How much money and how many trades are required to actually affect these stocks?

I’ve never really said how much I’m putting up to trade because I don’t want the focus to be on that. I want to focus on the result of what I’ve done, especially because the last stock price, which is supposedly how much the company is worth, is literally just the last stock price that was traded. That’s very much a representation. I’m dealing in the representation, not how much money I’m putting in.

I’m really interested in the sense of scale. The market is phenomenally large. If you include derivatives, there’s something like $900 trillion worth of assets traded. It’s beyond what you can imagine, and it’s not like you can measure it in comparison to anything else—it’s large in the absolute. The changes that I’ll be enacting here will look big, but if you put them in the context of the magnitude of the actual market, they’re tiny to the point of invisibility.

Where do you get the money to make these trades?

It’s my own money, so I'm blending me as an economic agent with me as an artist. It's a losing strategy, of course—it’s not like I’m making bank. There’s a good chance that I’ll lose money on this, but I’ll be happy if I break even. It all depends on my mood, on the market, and on the line I’m trying to draw.

The performance of the stock, of the exchange, on the exchange, 2015. © Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

The performance of the stock, of the exchange, on the exchange, 2015. © Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Do you have preconceived notions of what you want these lines to look like? Are you trading in order to achieve those ideals?

Yes. For example, I'd love to have a line that was just repeating up and down squiggle. Some will be very dramatic, with a big up or down swing. Maybe I’ll have a painting that lasts for a longer period of time, so it stays flat until all of a sudden it hiccups at intervals, like a heartbeat.

There’s only so much you can control, and you can’t go back with the market. You can only go forward as you draw, so I can only move the line up and down. That’s a limiting factor, but I’ll hopefully still be able to show intentionality and gesture and drawing at the same time.

There always has to be someone on the other side of the trade, buying or selling. I like that my line is contingent on somebody else, on another viewer or performer.

One of my favorite parts of your earlier “Stock Performance” was how the project made a fine art object out of something that is now part of financial history. Someone with no idea of your intentions could look at the stock of Golden Enterprises over the course of your performance and see a version of the line that you drew. How do you think about this interplay between the paintings that you’re making and the financial documentation they’re based on?

First of all, I think about it as a type of depth. To me, the fact that the paintings are echoed in these financial records is depth. There is a question of what will last longer. How long will those financial records hold the evidence of my performance, which essentially scribbles into the market “I was here”? Who knows if that will last longer than these paintings—paintings can last a really long time depending on how they’re circulated.

In terms of creating an art object from this, I’m interested in bringing together the virtual being and the physical being. Sometimes money just seems totally intangible, like air. You see it go up and down, but it doesn’t actually mean anything. Here, I’m making it physical by bringing it through my body and making it very dramatically gestural.

There’s a long tradition of art and finance being intimately—if not explicitly—linked, from the Medici family all the way to Jeff Koons, Jeffery Deitch, and the myriadcollectors and gallerists who entered the art world from a finance background. As someone who is making art with, rather than for, investment, how do you see yourself fitting into this tradition?

I feel like this project is more honest, in a way. Sometimes I have ideas that are even more market-related, and people say, “Whoa, careful. We don’t want this image of the artist-as-businessperson. The artist is supposed to be removed from that.” Art is supposed to fit into the capitalist system without seeking a profit, which of course is what everybody else does all the time. I think this might be more honest about at least part of the role paintings have today.

I think some people will view this as a critique of the art world. That makes sense since we’re in the art world and used to seeing things in those terms, but I think that ultimately this is showing you how representative value is, that it truly is just an image that we’re trading and creating. The market itself is a medium—it’s just as malleable.

Painting in the 20th century focused on its essentiality as a medium as a way to remove itself from the commodification of the rest of the world. If art since then has been a continuous attempt to separate itself from the market before the market finds a way to reabsorb it, what’s the next step? How do you actually break that chain?

Many of us assume an implicit critique whenever an artist talks about money or capitalism. Here, it seems like you’re taking a more neutral or even positive view of these subjects, saying, “Look how strange and almost wonderful this system is.” Is that how you’re working with these subjects?

Yeah, totally. There’s this trouble when you try to walk that fine line between being critical and being complicit, that you might not be critical enough and thus become complicit yourself. Jeff Koons is a good example—you can’t tell where he’s coming from any more. Damien Hirst is another—is he reveling in it or just the opposite?

I don’t think I’m necessarily trying to critique, and I don’t even like the idea of holding a mirror up to the subject, because I think I’m doing something else. A mirror image is a reflection—it’s not real. What I’m doing is real. I’m trading these stocks. That’s one thing I’m really into with my work, that it’s not just a model for something or a realm of possibility. I’m actually doing this.

Installation view of "Stock Performances" at 303 Gallery, New York, January 8—30, 2016. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Installation view of "Stock Performances" at 303 Gallery, New York, January 8—30, 2016. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Sitting in this empty room with just a desk and these blank white canvases, I’m struck by the different aesthetics these projects take on. In contrast to the minimal, almost austere look in here, Bitchcoin exudes a kind of colorful irreverence in everything from the name to its packaging. Is the presentation something you dwell on?

There is this really aggressive quality to both Bitchcoin and the stock performances. Bitchcoin clearly has an element of aggression starting from the name, but here I’m fucking with the stock market and then scribbling it on a painting. In a way, it’s very in-your-face. It’s a good thing I’m a small girl—imagine if I was some big dude. It would read very differently.

You have undergraduate degrees in international relations and finance from the University of Pennsylvania College of Arts and Sciences and the Wharton School respectively, plus a photography M.F.A. from Yale. Did you know as an undergrad that art would be a direction for you?

No. There was no way. I took a photography class at Penn, and it just snowballed from there. I started taking art at Penn as a sixth class in my busy dual-degree schedule. I ended up taking an "uncreative writing" class with Kenny Goldsmith, and at the end of the semester he sent me an email that said something along the lines of “If you become a stockbroker, I will shed a million tears for the artist you could have been” [laughs]. Later Terry Adkins—who was my advisor—pushed me to apply to grad school. I didn’t want to go to grad school, but Terry was like, “Knowing you, if you don’t do it now, you’re not going to want to go back to school.”

It’s not that I didn’t like finance—I enjoyed it, and I would have been fine doing it. I just felt this urgency in another direction. It was really tough at the time, because it wasn’t like I was just choosing to go into art—I was already doing something else that I had to say “no” to. I had to get the internships, get the offers, do all of that, and then say, “No, I’m not going to do this. I’m going to go for something that I have no real experience in.” At the time I decided I was going to be an artist, it wasn’t like I had gotten into Yale for an M.F.A. I had nothing besides a gut conviction that I wanted to do it.

You come from a finance background, correct? That must have made the decision even harder.

Yeah, my whole family works in finance. At the same time, though, it was also a kind of risk management. If it didn’t work, I could always go back to business. I knew I would have regrets if I didn’t at least try it. The thing is, when I decided to pursue art I had no clue that finance would then become part of my work. No clue whatsoever. At Wharton, I was making art about sexuality and gender politics. It wasn’t related to finance at all.

My first taste of the idea was a project I did where I took pictures of a girl nude in the main sections of the Wharton Building. She was another Wharton student, and we did it while we were still at school and thus still under the school’s rules, which are notoriously vague to allow the schools to do whatever they want. On the last day of school, I released a website that was selling postcards of these pictures. Within a couple days, 15,000 people had seen it and everybody at school was going crazy because they were familiar with the space. That’s when I got the first inkling of what I could do with art. There’s this nude girl, a student, in these powerful positions within this overwhelmingly male architecture. There’s the push and pull between critique and complicity, and there’s also the power play—we obviously weren’t supposed to be taking these photos there, so there was a question of whether the school was going try to take action. In the same way, the “Stock Performance” flirts with what could be called market manipulation.

Golden Enterprises on May 30, 2014, 2015. © Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Golden Enterprises on May 30, 2014, 2015. © Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

That’s an interesting point I didn't even consider. Are there potential legal ramifications for what you’re doing here?

I’m just trading, as far as anyone else is concerned. I just happen to be trading for visual change. At the same time, I don’t know if getting in trouble would actually be a negative outcome for the artwork or performance itself.

That’s one of the nice things about being an artist—sometimes getting in trouble is a good thing. Are you nervous at all?

It’s all really contingent upon the market itself, so my only concern is that I won’t be able to move the stocks well. That’s what crazy about this, but that’s also what makes the stakes real.

One of the things I’m talking about at the opening is that markets have a very reflexive nature, where a stock is supposed to represent a company even as it affects the company it represents. If a stock does really well, a company might be able to borrow on better terms and then do something with that money that then actually improves the company. There’s so many different ways that a stock price can affect the underlying company, so it can become a feedback loop.

The other feedback loop is that, as an investor, you’re both judging or seeking to understand the market—so the market is a kind of given—while at the same time seeking to participate in that market, in which case your understanding is the given. The thing is, when you participate in the market, you’re also affecting its reality. The market becomes a space for uncertainty, a space for creativity. In my performance and paintings, my body becomes part of that feedback loop as I walk from the computer to the canvases to make the paintings.

In addition to those paintings at 303 Gallery, you're also exhibiting artist’s books that feature specially-made gold nanoparticle paint. What form will these books take, and what exactly are gold nanoparticles?

I’m going to be working on scrapbooks while I’m here doing my trading. I’ll be putting things into them like scraps of the fabric from my dress, notes about the times and amounts of trades that I’m doing, smudges from the oil stick left on my hands, and bits of text. The last thing that I’m going to put in is some paint made with gold nanoparticles.

Gold nanoparticles are too small to see, but they have an optical property called surface plasmon resonance. My understanding is that the free electrons in light oscillate at the surface of the particle and then reflect a color, which is a different way of seeing color from how we normally do. This process can create different colors, from purples and reds to blues and even greys. The color is directly related to the size and shape of the particle, which can take the form of a sphere, rod, square, et cetera. It's just mind-boggling.

For the scrapbooks, I’m essentially making paint with these nanoparticles by mixing them with a medium. There’s no pigment in these paints—it’s just gold in different shapes on the molecular level. You’re seeing the result of these nano-relations.

How does this connect to your stock performances?

They both ask the question, “Where is the art located?” Is the art located at the moment when I’m drawing on the stock exchange? Is it located when I draw it on the canvas? Is the viewer the person in the market who sees what I’m doing, or is it the person in the gallery? It's a whole system of those relations. It’s a similar thing with the gold—is the moment of understanding when you know, “Oh, this is gold nanoparticles,” or is it seeing a really iridescent, beautiful color that isn’t gold.

© Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

© Sarah Meyohas, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

In addition to these various projects, you also run a gallery out of your apartment. Do you see that effort as at all related to the topics we’ve been speaking about?

People have said to me, “You need to be careful. Are you an artist or a gallerist?” in the same way that they asked, “Are you doing art or finance?” It’s like, come on. I don’t need that categorization. In that way the gallery is part of my work.

It’s interesting. First of all, it’s the place where I live, so it’s become part of the identity of the space. You’re quite literally coming into my home—it’s not a public space. It’s kind of a lifestyle [laughs].

How so?

As an example, I don’t have a table to eat on in my kitchen right now because there’s an installation of the dirtiest carpet you could possibly imagine with bleach stains that then become symbols that you project information on—it’s disgusting. My windows are blacked out right now, because that was another piece. I haven’t seen the view from my living room in weeks. That said, I like living in other people’s art. It’s art that inspires me, and it's also an affirmation of taste.

Can you say more about that? The question of a gallerist’s taste is something I think most people understand but isn’t often discussed.

A gallery creates a brand, right? I think that super top-tier galleries can represent artists that are all over the board, so there isn’t one key aesthetic that defines them, but galleries really are tastemakers. It’s about bringing other people’s work under my umbrella and into my home.

It’s important that this isn’t a storefront space that I’m renting—it’s my private apartment, which allows work that is fundamentally uncommercial to be shown for weeks on end without the pressure of selling. This current show has been really interesting because it’s very good work that would be difficult to sell. Then again, I’m not trying to fool anyone into thinking this is a real gallery rather than the place where I live.

This goes back to a contemporary, underlying question of where the space for showing art is going. In the past, people owned objects and had spaces that they owned for the purpose of showing those objects. It seems very territorial, whereas now it seems that art has become more relational. It’s more about the network of people, with social media as the best example of that. With the apartment gallery, a lot of the work that I’ve shown is not super commercial. Right now, I’m more interested in building a community.