As the medium of painting continues its tortuous transition into the 21st century, where a digital-first outlook is coloring every aspect of our lives, one of the most intriguing young painters to look at is Louisa Gagliardi. A 27-year-old native of Zürich who trained as a graphic designer at Amsterdam’s storied Gerrit Rietveld Academie, she has spent most of her career doing commercial work for brands like Kenzo and Hublot—in fact, she only began making paintings in the summer of 2015. Since then, however, she has experienced a remarkably rapid ascent up the curatorial and commercial rungs of the art world. Today, she is a star-in-the-making.

How did that happen? For one thing, her paintings—“paintings,” really—don’t look like anything else out there. Moody, uncanny, oddly lit, and uncomfortably sensual, they brim with an implacable sense of unease. The figures in them seem equally related to adult MTV cartoons and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s alienated demimonde-dwellers—and, in fact, they are deeply rooted in art history. They seem very present-tense, which may explain why early on the globe-trotting duo behind 89+, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Simon Castets, decided to include her work in their “Filter Bubble” survey of Post-Internet art at the LUMA Foundation in Arles.

Now, Gagliardi—whose rising stardom has been well managed by her dealer, Tara Downs of Tomorrow Gallery—has been included in Phaidon’s Vitamin P3 survey of contemporary painting as well, denoting her as one of the artists leading the medium forward today. To talk to her about the ideas and process behind her work, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Gagliardi as she was finishing up the La Brea Studio Artists Residency in Los Angeles with the collector Danny First, which culminated in a show of new work the precise replica of Ted “The Unabomber”Kaczynski’s cabin that First keeps in his back yard. (The space is “pretty heavy content-wise,” she says.) Ah, the life of a Post-Internet artist.

You’re young and technologically savvy, and you started your career doing these highly mechanistic, digitally inflected illustrations for magazines. Why, out of all the different modes of art, have you now become drawn to the venerable tradition of painting, and figurative painting at that?

I did my studies in graphic design, and during this time I became interested in illustration. I liked the aesthetic of it, especially when done with 3-D rendering. Instead of using a very safe tool, it gives you the opportunity for mistakes and try-outs—there’s much more freedom. I would make these images that were much more out of control, that came out very angular, very planar. But I was really afraid at the time to have any figures in there, so they were human-less for quite some time.

Eventually I dared to add figures—still, they were very Fernand Léger-looking, very digital. I did this for two or three years and they started to get attention, so I would be invited to make images for magazines. But I got really sick of it and wanted to do something new. Now my paintings are mostly digitally drawn, which is a more free-handed way of using the computer. This is a long explanation to say that either what I was doing before was already painting, or maybe what I am doing now is not painting.

Am I really a painter, or am I not? The process hasn’t changed that much. I still use the same program, it’s just that I have much more freedom within the images I am making now. They don’t come from the skeleton that I was using before.

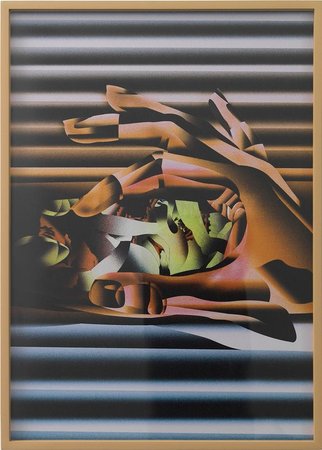

Incognito Mode 1, 2015, available on Artspace

Incognito Mode 1, 2015, available on Artspace

It’s so interesting that you mentioned Léger when you were talking about your more machine-like illustrations, since he’s absolutely proto-digital—his art, which he said was inspired by the sight of a piece of field artillery bathed in direct sunlight, transmuted the human body through the aesthetic of his generation’s form of disruptive technology. How did you come around to that connection?

I was a huge fan of Léger when I was doing my studies. It was so graphic and so composed and I wanted to appropriate its style to the visuals I could make. He spoke to me on many levels—the figure itself, the gradients. It is the perfection of what I wanted to do. It has this free yet gridded nature, a reticulated gradient he would use and that could transform images into pretty much whatever he wanted. He had these tools for combination that were incredible. He fascinated me.

The artists of his generation, like the Cubists and the Futurists, were reacting pictorially to the traumatic changes wrought by the new machines of World War I battlefields and elsewhere. Today, 100 years later, we are dealing with a different kind of revolution in technology. Back then they were talking about how the body was torn asunder by machines; now, in a different way, the body is again being recontextualized by digital technology. Do you see yourself as having a kind of link to these Modern artists?

I think they were commenting on these things, obviously, and I suppose I am as well in regards to the figure. How do you represent yourself? There is a strong link to social media in my work. The way I use light suggests the presence of screens outside of the picture plane. We are alone but never really alone—this digital window through the world is always there.

So, why did you eventually decide to begin adding figures to your work?

I have always been afraid of using them—they can be so off so easily. But it was a natural evolution. I had done so much dealing with spaces and architecture that I wanted to see where they would lead me, because using the figures can allow me to tell so much more of a story than just playing with spaces. With figures you can express everything. Still, I am kind of wondering about this question myself. Let’s go back.

The first series of figures that I did for my first New York exhibit were these really up-close portraits. I took the inspiration for these portraits from the idea of social gatherings—for example, an opening. I would collect these moments of being surrounded by other people—the feeling of being uncomfortable, the way you know those around you but you don’t really, the way your gestures change. I noticed there would be a lot of hands in play, holding beers or picking at fingers or smoking cigarettes.

At the time, in Zürich, I was feeling this lack of confidence and discomfort, and the work reflected my mood in these moments, which was something I really wanted to express. From then on, I thought, “This is working.” A new process was born from that. I saw all the potentials of what could be, and more and more I was zooming out or zooming in to hyper-close-ups. In the pictures I’m working on right now, you can see full bodies and multiple figures. But I am still being very careful, because it is a difficult thing to make work.

Peach Fuzz, 2016

Peach Fuzz, 2016

What about the tenor of your paintings? They are deeply atmospheric—mysterious and with a touch of ambiguous eroticism, as if at some bleary after-hours setting. Where does that come from?

For a recent show, for instance, I wanted to show the intimacy of a pretend couple overlaid with a sense of voyeurism and mysterious nervousness, like, “This is our intimacy, really. No one can see us.” But yes, they can. I wanted this feeling of insomnia and the fear of the next day, being half-awake and with someone you don’t know really, when you awaken to this sense of reality but it’s not really reality. I like to show this conflict. There is a lot of sensuality—I like to show the beauty of two bodies together amid a sense of a voyeurism.

Why voyeurism?

We are in an era of voyeurism. To post or not to post? You can’t do a show and put this other painting somewhere—people will know about it. Everything that you put out there will be seen. You can go on Facebook and decide you don’t want to be tagged in a picture, but it doesn’t matter—people will see it.

And that’s even without the government getting involved in surveillance. It’s just basic, everyday life.

Exactly! It’s out there. If you want to do something that no one knows about, you just don’t do it. It’s a scary feeling, and that’s also a tool I use. I try not to fear it—it’s become natural. But whatever I do, it’s in the back of my mind—this pressure from yourself, from your peers, from people you don’t know.

I think that comes through in your work. Together with the eroticism there is an incredible amount of anxiety. The images are unsettling. Can you talk a bit more about the anxiety in your paintings?

When I was doing my previous work, it was always for commissions, so I felt very comfortable because everything was very clear. Clients would give me a brief and come to me with an image that they had in mind. I had this freedom, but once I showed them what I did maybe they wanted something more blue, or more green. Suddenly, one day, I did this series that was more painterly and put the images on my website. I had no idea how they were going to be received. Soon a gallery contacted me and asked to show the work. It was Alex Ross, who was curating the “Madrugada” duo show with Fay Nicolson. We begin a conversation about how I would like to show it—is it an edition? Et cetera.

But that’s not important. What is important is that from one day to the next my work was recontextualized, and of course I was really thrilled. In my heart, painting is the most beautiful and sacred and true. The word illustrator is thought of as “dirty” in a certain way. So in making this transition there was an immense pressure I put on myself. I had the feeling of being a fraud that had been haunting me for a long time. Who am I? Am I a painter? Am I an artist? Does it matter what I am? Am I simply a graphic designer? I still have this anxiety.

What’s comfortable about being an illustrator is that if the work is not liked, it’s still okay—it’s not yours, really, so you’re okay to make concessions on the color or maybe the size. With art, it’s your piece, and reflects upon you alone. I didn’t study art, so I have a lack of confidence there. How do I speak about it? Now I am starting to become more comfortable and don’t ask myself these questions, but the worry is still there.

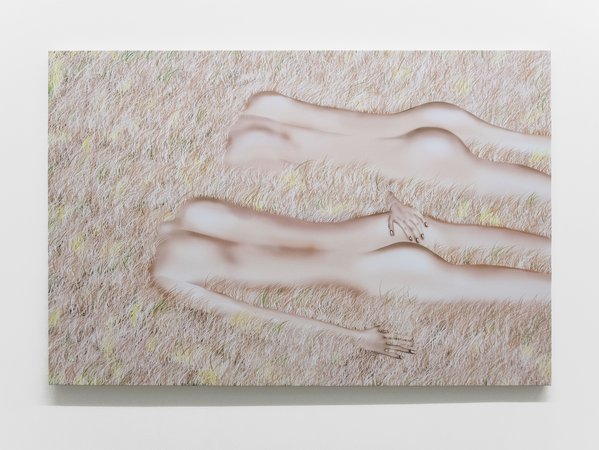

11:30 p.m., 2016

11:30 p.m., 2016

It’s funny, because the anxiety in your art can be read as a kind of broader generational anxiety, but here you’re saying that it comes from your nervousness about making art. It’s a bit like method acting, where you dig into something you feel deeply and authentically and then are able to share it with the audience in a different form.

I want to turn this energy into something that I hope is beautiful.

It’s amazing how you had your first big break simply by posting your paintings on your website. How did that happen? How did these gallerists and curators know to follow you in the first place?

Because I had worked with many brands and magazines before that, and because I had done a lot of commissions, my art was out there—it was just seen as more illustrative work. But when I posted those first four paintings it had a snowball effect. As soon as they came out on my website, I also had Ellis King in Dublin contact me pretty much at the same time. In fact, in that first month, I received four or five offers to do shows. It was weird and exciting, of course. I was worried I had made some bad decisions, at first.

That kind of first wave of attention is a time when many artists make critical mistakes. What did you do wrong?

I just got overly excited and said yes to too many things without thinking. I’m lucky that my boyfriend, Adam Cruces, who is an artist and been in this world for a long time, gave me some great advice. And Tara Downs [the owner of Tomorrow Gallery] was amazing at this moment. She was really sweet—she must have pulled some hair out of her head, though. My advice for other artists going through this would be: take your time and don’t sell too much all at once. If the people really like the work, they’ll be patient. It comes back to my anxiety about being an artist. But if they really like it, then that’s what matters and they will stay. If they don’t, then it’s because they want you because you’re “hot right now” and they want to make money, which is offensive to everything that I stand for, somehow.

To go back to the paintings themselves, they actually started out as purely digital files, is that right? When did you realize your first one as an actual physical object?

The first one I produced was shown last summer at Ellis King, I think. It was called Cookie Gate. That was the very first one for my first “real” show. None of them were from that first batch of four I posted online—I made new work for it.

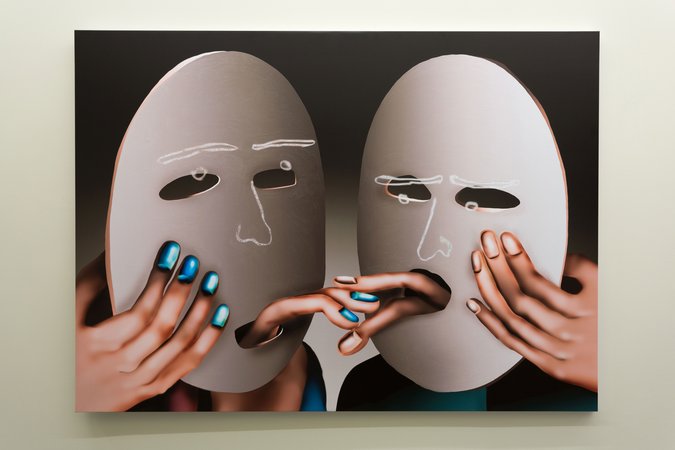

Rubberneck, 2016

Rubberneck, 2016

What is the process behind your paintings? How do you make them as digital files, and then how do you make them as “paintings?”

To be super technical, I start by sketching by hand. I make a rough sketch of what I want the painting to look like, and then I scan it and roughly trace it on the computer to make zones of colors. It’s really rough at the beginning and really looks like Color by Numbers. From then on I move it to Photoshop—I guess that’s really where the painting comes to life. I open these rough color zones and start shading and adjusting the composition, everything. In photoshop I will have like 32 layers of different shading and different forms. Once the file is ready, they are printed on the PVC. Then, after printing, I add one or two last layers, which brings the last touch of life that I can give to the paintings.

It started with the “Madrugada” show, where I added nail polish—I had a painting of person with their hand in front of their face and I painted the nails on the fingers with nail polish. The hand is a beautiful accessory, but also protection from the world. But this is important for me: I only use non-paint, if that means anything. Mostly I use things like a latex gel medium or varnish. I will not use paint, funnily enough. I’m very worried about it. It was a thing from the beginning. I once tried printing it on canvas, and it seemed like I wanted so badly to sell it as a painting, you know, and not be proud of what it was, which was a digital image, or digital painting. I felt I wanted to embrace that instead.

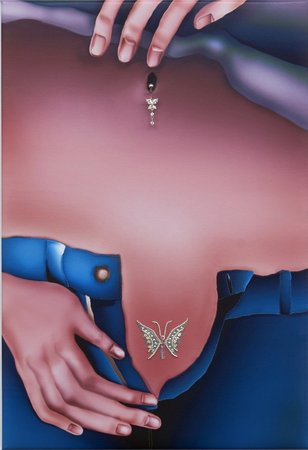

Also, non-paint material is very sensual and plasticky. I knew if I touched it, it would be greasy, and I liked that. It was a reminder of the glossiness of the screen. I do a lot with skin, which also has this texture that vinyl has. For a recent show dealing with body modifications, like piercings and tattoos, I actually pierced the canvas—a pierced arm, a pierced nose, a pierced nipple, a pierced labia. I am trying to explore these elements, but also not make them too regular or formulaic. Again, I want to embrace what I’m making and not sell it as a classical painting, so I don’t add a last physical layer to all of them. If it’s not necessary, than I won’t.

Pierced Belly Button, Vajazzled Pubic Area, 2015

Pierced Belly Button, Vajazzled Pubic Area, 2015

That’s very interesting. Do you know of any other artists who are working in a similar way?

I would say Petra Cortright, who paints completely digitally. I know other artists who do sketches digitally. I also know other artists who are either excited or disappointed that my paintings are not airbrushed. A lot of people tell me I should airbrush it—that I could do the sketch on the computer and then redo it by hand. I thought about it, but then was like, “No. Why?” Why do something for it to have this physical gesture to it if it already works? There is a physical gesture!

It sounds like your anxiety about painting is a secret weapon.

Maybe. I want to believe it!

I learned in the very nice statement you wrote for Phaidon.com that your godmother is an art historian who specializes in religious paintings. When I read that, it opened up a whole new way of looking at your work, considering the prominence of the hand in your art. Hands are so important in religious painting.

When I was a kid she would take me to Venice, Rome, the Louvre, everywhere. As a kid, this can be really dreadful—you have huge rooms with all of these paintings and you just want to rush through and have it be over with. But she would choose two or three paintings in the whole Louvre for us to look at that were so loaded with the history of the bible, of symbols, and she would make the experience of looking at them extraordinary. She didn’t always show me religious work, but she did specialize in them.

I was always fascinated by the hand, because they would point, they would tell the story of who is the ally of who. I think about the Christ, with the gesture of two fingers—a human and God. She would always tell me that I had Renaissance hands, which is totally not true. I think she was trying to make me feel better about my ugly hands.

That sounds like a nice thing to say.

I know, but it was wrong. I also loved these elongated bodies, like the Odalisque of Ingres. That a is one of my favorite paintings, because she has a freakishly long back. This fascinated me. My first bodies were all elongated. To go back to my godmother, she just made these paintings so exciting and gave me the keys to appreciate and love them.

Its funny, because the one thing that is largely absent in our Western cultural world is any kind of religion—there’s no greater, higher power in our popular culture. Is there symbolism that you include in your work?

No, there is no relation to religion in my work, but I am fascinated by religious paintings. It is not something I think about when I do the work. It’s the same with gender, if I may go there. This is something I have been asked about quite a bit—“Are these men? Are these women?” That is something that scares me as much as painting. As soon as you bring in a gender, it becomes something else. I think this takes so much power from the painting and it is not something I am ready to use. It becomes a symbol right away—a man and a woman, two men, I stay clear of this for now.

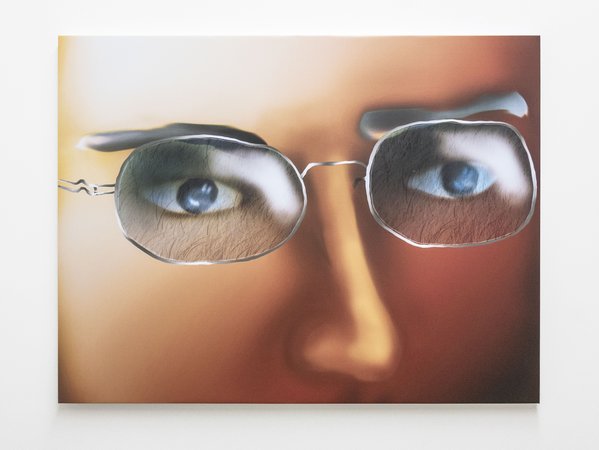

9:30 p.m., 2016

9:30 p.m., 2016

It’s funny, because I always made assumptions about gender when looking at your paintings, that one figure was a man or a woman.

There was one show where it was really clear, for sure—the one with the body piercings. Otherwise I want to believe the figures can be either, and it is up to you to decide what is what. It’s more of an essential moment that I want to create. There is sensuality, but you don’t know who is who in the relationship. It’s interesting that you say it’s clear to you.

Speaking of the specificity of who these people are, is it true that many of them were drawn from your social media circle?

They were at the very beginning, and the first images were named after specific people. At this time I was doing close-up portraits based on the attitudes of those I had seen or photographed. At that time identity and gender was more attached. For me these are about mood, it could be a man or a woman, but this didn’t matter.

You stopped using these actual reference points of real people, is that right?

Yes, it stopped after my first show at Tomorrow. Let’s say it stopped when I did the next series of work for the solo show at Tomorrow. There were two figures, but they were coming out of a story I wanted to tell of intimate space rather than a real relationship. This was fantasy rather than reality.

So now you make your figures up entirely?

Yes.

Your work has really struck a chord among curators—early on, for instance, you had Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Simone Castets really getting behind your work. How did you come to their attention?

That is a great question! I think it was Simone Castets from the Swiss Institute who saw the show that was at Tomorrow in September of 2015. At the time they were curating that 89+ show in Zürich at the LUMA Foundation, and I think Simone told Hans Ulrich Obrist about it. They sent me an e-mail saying, “We really love the work—you’re from Zürich, would you like to participate?” Yes, I wanted to participate! So I think it was Simone who saw the work and shared it, but I could be wrong, honestly. That is my theory. Obrist was in Zürich, so I had the pleasure of meeting him. It was wonderful—I was nervous as hell, of course.

How are you dealing with selling your work? A year ago you were primarily working on commissions with designers and other clients, and now you have gotten into this whole other marketplace, and a whole other way of doing business? How have you made that transition, and how are you managing the collectors who want to buy your paintings?

I have been warned so much about who you should sell to, who you should not, who is a flipper, who is not—all of that. “You should not sell to him, but you should sell to him.” To be honest, Tara has been my guide. I will often defer to her. I will direct collectors to her, because I just don’t know. I have heard terrible stories. The best way to deal with this is to trust someone close to do it for me.

Works on display at the Swiss Institute Roma

Works on display at the Swiss Institute Roma

And now you are out in L.A, where so many of these flippers live.

I have met some of them—it’s pretty awkward. There are all of these huge galleries here, and it’s kind of scary—warehouses and enormous places! There are, of course, great galleries and humans, but there is this other side that’s kind of like the stock market. I feel uncomfortable having an opinion on this topic. I don’t really know enough. It’s another level of threat that I don’t really want to deal with. I would rather have someone else deal with it. I am very lucky that Tara is a very strong woman and a very good ally in this.

We talked about the ways you use digital tools to create your work. How are you using the internet as a tool for what comes after making the work?

I think social media is a great way to promote a show. It doesn’t validate the work, but it feels good to get some “likes.” There is so much anxiety beforehand, when you have done all of this work and the opening is happening. So, before I really used it as a promoting tool, but now it also serves as a moment where I can be proud of something I made and share what I have been working on. I hate saying no and this has gotten me quite a few offers, but I cannot stop myself from posting a little piece to say, “Hey, this happened.”

Do people reach out to you to try and buy directly from online?

Yes, and that’s such a red flag. In my guidebook of what to do, I know how to deal with some of this, and when you get a message on Instagram… it’s not a good sign.

Have you ever shown your work online, in digital exhibition context or something like that?

Like, a work that only existed as a digital image, you mean?

Well, your work has a foot in both areas.

I would say that with my previous work as an illustrator that may have happened, but actually no. I think I have to say no.

If you as an artist are making use of all of these technologies, why aren’t more curators or gallerists making use of them as well?

I couldn’t name them, but I have seen some of these online curating platforms. This is a good question, because, I wonder if my work digitally would match the kind of physical object they are at the end. I would have to think differently if they were just online—I feel that the physical part is quite important as well, the feeling of the material, like skin. But I don’t have an answer, and I’m really curious.

Your career is taking off, but I hear you’re still working on some graphic design projects as well. How have you been balancing the two?

I have kept graphic design for two main reasons. First of all, I love it. It’s what I have studied, I feel comfortable doing it, and I know what I’m doing. I’m a super confident graphic designer and a super un-confident painter, let’s say it like that. This keeps me balancing my anxieties. Also, to be totally unromantic about it, this momentum that I have and attention that I got was so fast and unpredicted, I’m really scared it could go away quickly as well.

I want to stay realistic—maybe I shouldn’t. Maybe I should just totally go for it and believe in myself, but there is this little voice in my head saying, “Hey! Keep your feet on the ground. This could be over soon.” I would never stop painting though. I don’t need the commercial work right now, really, but it is for peace of mind. In any case, I love it.

That sounds very sane, which is refreshing after watching too many artists who become overnight successes go too fast, doing everything that is offered to them and selling work to everybody that wants it. In a year they go from just starting out to being a sensation to becoming a cautionary tale, like a Hollywood child star from the ‘80s.

Yes, I’ve seen this. Like everyone, I have heard these crazy stories—the paintings going for crazy amount of money, becoming a superstar, and then, “Where is he now?” I know it can happen. I prefer having an easy start, and I feel that in that way I am very unromantic. I work very well in the morning, and not well at night. I don’t have any kind of rock-and-roll artist vibe. But what I just said is super cliché, and every artist isn’t viewed that way! Maybe I am very Swiss, a little too pragmatic.

Illustrations for L'Officiel Suisse

Illustrations for L'Officiel Suisse

What kind of clients are you working with on the graphic-design side?

I work with the museum of my home town—they were my first client and I feel at home with them. I work mostly with institutions. I don’t take on illustration anymore—it’s a bit too limiting for me. I prefer doing books, posters, and communications.

Going back to your gallery and museum work, are there any artists of your generation that you see as being your peers or confederates, creatively? Who are the people you see yourself working alongside?

My partner, Adam Cruces, is a huge motivation to me. For each project he will do something out of his comfort zone, always site-specific. He never will use something again that he has done before. That kind of blows my mind—it’s so nerve-wracking, and the fact that he has the confidence to do that every time is an inspiration in terms of believing in what you are doing and not caring about what people are expecting of you. So he is one peer in the most direct sense. We also collaborated on some projects, and we have a site called Couple.work where we show the collaborations we’ve done.

To go on to others, I am in love with Zoe Barcza’s work. She has great paintings, and she is such a warm person, I had a chance to meet her when she had a show at François Ghebaly here in L.A. Her work is great. As far as other painters, Sanya Kantarovsky. He makes a figure with a bit of a cartoonish touch so beautifully and so refined. There are so many different feelings that come out of it. He did this projection piece at Unlimited in Art Basel and it was so beautiful. I was like, “Oh my God, I hate him.” [laughs] It was a beautiful idea.

Would you ever do something like that? Do you see yourself going into directions other than painting in your fine art career?

I have been thinking of doing something, and I’ve been doing some tryouts. It’s not the time yet, but it’s definitely in the back of my mind. I don’t know how yet, and that’s why I think the collaboration with Adam is so important to me. I get to explore something to use for myself, I suppose, and see where I could take it next.

To end on a different note, I read that you went through a skateboarding period when you were younger, working on a skateboard magazine and dabbling in graffiti. What kind of graffiti did you do?

I was not a graffiti artist per se, but I was super into it, graffiti being so graphic. I did a few pieces on paper that were super embarrassing. I made a whole magazine by hand and everything, sort of using this code of graffiti as a design element. It’s cute, more than anything. It’s not the badass thing I wanted it to be, but of course it was teenage me using arrows and shading. You know, with my dry pastel on paper in my room. It was a very Swiss version of graffiti!

(related-works)