Here’s a story for you: in 1916, the Irish poet W.B. Yeats penned a play called At the Hawk’s Well , based in part off of a translation of the Japanese Noh drama Yōrō by his assistant, the up-and-coming American poet Ezra Pound . Taking cues from the traditional Japanese art form, Yeats attempted to fuse Noh’s music, dance, costumes, and masks with his Modernist sensibility, a combination that would continue to inspire his later works.

At the Hawk’s Well quickly took on a life of its own in Japan. As the director of New York’s Japan Society, Yukie Kamiya writes, “with the social and political changes that occurred in Japan the latter half of the nineteenth century during the country’s rapid drive toward modernization, many classical art forms fell into decline and lost their patronage, including Noh.” Into this void fell Yeats’s unusual and decidedly nontraditional play, which was translated into Japanese by 1920 and first performed in Tokyo in 1939. This version proved to be a recurring feature of the revitalization of Noh in Japan throughout the 20 th century, with various poets and playwrights reworking and restaging the performance in 1949, 1967, and 1990. “Thus,” writes Kamiya, “the impact of Noh on Western literature and theatre has come full circle, acting as a stimulus to Noh itself.”

Now, at a time when the ethics of cultural appropriation have become a flashpoint in the ongoing culture wars, the English conceptual artist Simon Starling is stepping directly into the fray with yet another reinterpretation of the hundred-year-old play. His version, called At Twilight —staged by The Common Guild in Glasglow earlier this year and reimagined as an exhibition of props, costumes, and historical ephemera, on view at the Japan Society through January 15 th —is a meta-commentary on precisely this process of storytelling, collaboration, translation, and misinterpretation, all filtered through Starling’s irreverent yet research-intensive process.

Starling is best known for his 2005 Turner Prize -winning project Shedboatshed , which saw the artist prying apart a wooden shed to build a boat, sailing the craft down the Rhine, and then deconstructing the whole thing to turn it back into a shed. It’s a simple example of his approach to art-making, focusing on cycles of transformation and especially the extensive backstories that often accompany such changes; as Anne Rochette and Wade Saunders write in Art in America , Starling’s output is part of “a long tradition of art whose full appreciation relies on a corpus of knowledge outside the frame.”

This impulse towards explication is certainly on display at the Japan Society, an institution founded in 1907 by a group of Japanese and American statesmen with the express purpose of promoting intercultural exchange between the two countries. The play itself is notably absent from the multi-room exhibition, available only as a text and in the form of costumes (derived from the few photograph’s from Yeat’s original performances, plus additions like a two-person Eeyore suit), masks (created in collaboration with the master Noh maskmaker Yasuo Miichi ), and a film showing the dance choreographed by the Venezuelan dancer Javier De Frutos for Starling’s Glasgow performance. The show also features a room of historical ephemera, from Modernist sculptures from giants like Brancusi to rare examples of classical Noh masks pulled from a number of private collections.

The result is a multifaceted show highlighting the collaborations, historical vagaries, and simple accidents that allowed for the extended evolution of this text over the centuries. Artspace’s Dylan Kerr sat down with Starling to find out how it all fits together.

Installation shot of "Simon Starling: At Twilight" by Richard Goodbody. Courtesy Simon Starling & The Modern Institute

Installation shot of "Simon Starling: At Twilight" by Richard Goodbody. Courtesy Simon Starling & The Modern Institute

Let’s start with the basics. How did the Yeats play that this show is based on come into being in the first place? What’s the backstory here?

Yeats had been involved in theater, quite heavily, for many years. He’d set up the Abbey Theatre in Dublin with Lady Gregory, but had become a little disillusioned with it—the need to fill the theater the whole time, dealing with the reactions of the press, so on and so on. During the First World War, he moved into a small cottage in the Ashdown Forest, south of London, and he lived there for three winters with Ezra Pound, who was his secretary. Ezra was half his age and a very ambitious American poet, and Yeats was the man in European poetry, so Pound offered himself to work with him. At that time, in 1915 or 1916, Pound was given a set of unfinished translations of Noh plays by the widow of [American historian of Japanese art] Ernest Fenollosa, who had died in 1908. Pound had a reputation as a translator, so he was given these works unfinished to give them some polish, language-wise.

It’s through this that Yeats got turned on to the possibilities of Noh theater. He understood that it had connections to his own interests in the spirit world, the occult, and to Irish folklore—things that he was already thinking about and working with. He also understood that it was a kind of theater that had a certain economy to it, that it was possible to make a Noh play with fairly modest means. I imagine that made a lot of sense in the middle of the First World War.

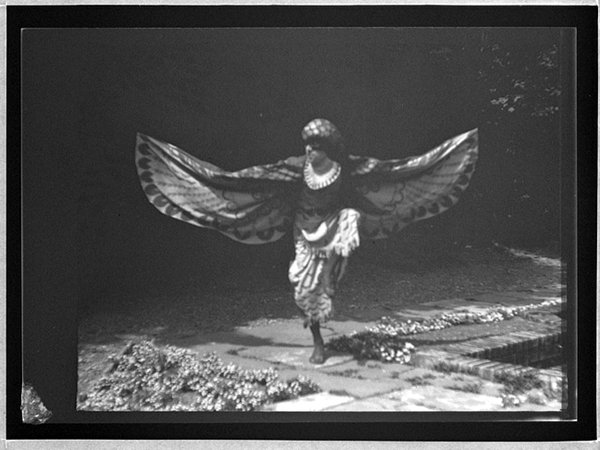

He wrote At the Hawk’s Well fairly fast. It was the first of a number of what he called “dance dramas.” It was performed for the first time in the spring of 1916 at the house of Lady Cunard in London, to a tiny audience. There were actually two performances in London at that time—they sort of hand-picked the audience: there were assorted aristocracy, T.S. Eliot turned up, and various other kinds of people were there. Very little is known about what actually happened. There’s a few photographs that Alvin Langdon Coburn made of the cast in the garden, in their costumes, but that’s about it. Yeats deliberately kept the press away because he didn’t want to deal with that—for him, it was a bit of an experiment.

Michio Ito as the Hawk in

At the Hawk's Well

, 196. Photo by Alvin Langdon Coburn

Michio Ito as the Hawk in

At the Hawk's Well

, 196. Photo by Alvin Langdon Coburn

Fast forward a century: how did you get involved with this very unusual and highly specific historical piece?

It was actually through another work I made six years ago for an exhibition in Hiroshima called Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) , which was my first engagement with Noh theater.

What did that consist of?

Well, the work itself was a film and a series of masks. The film documents Yasuo Miichi, the mask maker in Osaka, making a series of nine masks. The film is then overlaid with two narratives. One is the narrative of an old play called Eboshi-ori, which is a 16 th -century play about a young noble boy trying to escape from his past by disguising himself with a particular kind of hat. That was then collapsed onto the story of the evolution of a Henry Moore sculpture, which I learned about at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art when I went there for the first time.

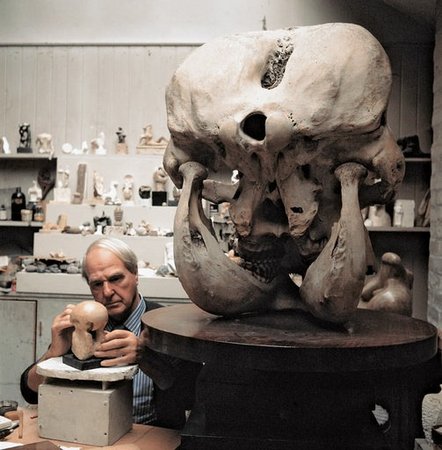

What’s the story behind that sculpture?

The Henry Moore sculpture has a very strange status in the museum, because it was bought as part of a deal. The museum has a huge bronze arch that they bought from Moore just at the end of his life, and that has since become a kind of logo for the museum. When they bought it, he said you can have it, but you also have to have this: a small sculpture he called Atom Piece , which is actually a working model for a large monument in Chicago called Nuclear Energy , which itself marks the site of the first nuclear reactor, Enrico Fermi’s Chicago Pile-1.

It was a strange commission to take on. When the Chicago people came to his studio to ask him if he was interested, they saw this small maquette he’d made. It’s clear that the maquette was made to look like a kind of death’s head—it’s a skull. The maquette for the sculpture was made the same year that F.H.K. Henrion, the famous graphic designer in Britain, designed this very iconic poster for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, with a skull in front of a mushroom cloud—they were actually neighbors for a while, Moore and Henrion. When Moore got the commission from Chicago he referred to that sculpture as Atom Piece , but the Chicago commission thought the world “piece” was a bit too much like “P-E-A-C-E,” so they decided that he should change the name—it’s a crazy story.

Subsequent to that, he also played with the history of the evolution of that sculpture. Six years after he made the original plaster maquette, he took that back into the studio and sat it next to a big elephant skull, which he hadn’t even owned when he made the original. Then he got his photographer to come and make photographs of him as if he’s making the piece for the first time.

Henry Moore working on the maquette for

Atom Piece

, 1970. Photo by Errol Jackson © The Henry Moore Foundation

Henry Moore working on the maquette for

Atom Piece

, 1970. Photo by Errol Jackson © The Henry Moore Foundation

As if he based the sculpture off the elephant skull?

Yeah. It was like a retrofitting of the story, to naturalize the object and to distance it from any politics.

I was interested in this idea of a sculpture having a double identity, partially because there was a big scandal in the ‘90s—somebody discovered that this Henry Moore sculpture they had in Hiroshima was actually linked to the one celebrating the beginning of the atom bomb project. There was a public outcry: “Why are you spending public money on sculptures that celebrate the beginning of the atom bomb project?” Ever since then, this object has had a very strange status within the collection. They don’t really know what to do with it. It’s a bit spooked, in a way.

Anyway, that was the beginning of this idea of coopting Noh theater as a comparative narrative device. When I was doing all the research for that project, I discovered that Yeats had basically done the same thing 100 years ago. He used a Japanese play called Yōrō , which is a story of two guys going in search of a waterfall of immortality, and then collapsed that onto this Irish folktale about a young warrior in search of the waters of immortality in a well. As 2016 came around the corner, I just thought, “Maybe this is a nice moment to think about that again.”

When I made Project for a Masquerade , a few people asked me, “Are you interested in putting this on the stage?” I was always very resistant to that, because it very fragile, sort of impossible proposition, and I always said no. Then Katrina Brown, in Glasgow at the Common Guild, sort of pushed me a little bit and said, “Well, why don’t we do something?” And I said, “OK, well what about At the Hawk’s Well ?” Slowly, this set of characters emerged around this moment—some of them fictional, some of them historical—and this play took shape. I dragged in a number of different collaborators and went back to Yasuo with some designs for masks, and it went on from there.

At the Hawk's Well (Grayscale)

, 2014. Masks by Yasuo Miichi; Costumes by Kumi Sakurai/Atelier Hinode; Courtesy of Simon Starling & The Modern Institute

At the Hawk's Well (Grayscale)

, 2014. Masks by Yasuo Miichi; Costumes by Kumi Sakurai/Atelier Hinode; Courtesy of Simon Starling & The Modern Institute

Can you give us a brief outline of what your updated play contains?

The play has three layers, if you like. The core of it is a restaging of this 1916 performance of At the Hawk’s Well . There are three characters directly taken from there. There was a very interesting and successful book illustrator, Edmund Dulac, who designed costumes for Yeats, but the only evidence of those are these black and white photographs from Langdon Coburn. We made these grayscale versions of those costumes. These three characters are the core of the play, and then there’s this other layer, which is the story of Yeats and Pound in Ashdown Forest, reinventing Noh theater. They fence a lot—Yeats was getting taught to fence by Ezra Pound at the time

You mean literally fencing?

Literally fencing, yes. 1916 was a moment where a lot of poets like Pound and Yeats were trying to work out what their relationship to the First World War was, and how they should act in relation to it: should they write about it, keep their mouths shut? What should they do? Of course, that then has some resonances with the story of the Hawk’s Well, with this warrior going in search of the water of immortality and so on. During that time Henri Gaudier-Brzeska—who was a very close friend of Pound’s—had just died in the trenches. There are some fragments of letters he wrote to Pound in the play, so it also connects to the war through that.

The other layer consists of the two actors who play myself and Graham Eatough, the theater maker I collaborated with on the piece. We are also characters—they’re our masks, if you like. There’s a kind of tussle in the play between my character and Graham’s character as we try and get this production together. I want to tell all the background stories, and he wants to get on with making the play. It’s a piece of theater, but at other times it’s more like an artist’s talk or a lecture or an art history lesson or something like that.

It all culminates in the hawk dance, which was choreographed by Javier De Frutos, a choreographer who’s actually Venezuelan, but works in London these days, and which we presented as a film projected onto the stage. The hawk is a kind of phantom character, a shape-shifting guardian of the well, who’s protecting the waters of immortality from mortal interference. We had Josh Abrams and his band from Chicago come to play music, which was amazing. They sat like a Noh orchestra, cross-legged on stage, and performed. That was the form of it.

We performed it outside in Glasgow at twilight, which is a special time in Japanese culture where there’s supposed to be a portal opened up between the mundane world of the living and the spirit world. It was a very nice—it didn’t rain, even. It was amazing. So, yeah, we were lucky.

As I’m sure you’re aware, the issue of cultural appropriation is extremely contentious right now. How do you ensure that, as a white guy from the West, you do justice to this ancient Japanese form?

One of the interesting things about Yeats’s play is that if he had really known anything about Japanese culture, it would have been impossible. It’s a hugely intricate tradition. If he’d really understood it, he would have tried to replicate it. But he knew a tiny amount, almost hearsay. The only person actually involved in the original performance who’d ever seen a Noh play was the dancer Michio Ito, who claimed to dislike Noh theater terribly and to have only ever seen it once as a child in Japan. In a sense, that lack of knowledge allowed them the space to generate this new form. Yeats took some inflections and some modes from the Japanese texts he was able to read through—Pound’s translations—but he knew very, very little. In a way, the whole project is about the possibilities of reinvention through not knowing, rather than knowing.

I’m also no expert on Noh theater whatsoever. I’ve been to see some Noh plays in Japan now, and I’ve read a lot of material about them—but it’s a tiny little scratch on the surface about what that culture’s about. When I showed Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) in Japan, I was a little bit unsure about it because of course, as you say, it’s a hot topic—it’s something that you don’t do lightly. At the same time, the response to what I did was so extraordinary and positive. It is a fairly irreverent and at times perhaps lightly iconoclastic approach to that tradition. It is about trying to make something new, fundamentally, that talks to that tradition. And it seemed like an interesting proposition, to bring that whole project here, which, of course, is a very particular context for showing something like this.

The Japan Society itself was originally founded to promote this kind of exchange.

In a way it’s nice—it brings the whole thing full circle. Hence Fenollosa—who was a very important conduit for Japanese culture into North America at the turn of the 20th century and was also a very important figure in Japan—was given a state funeral in Japan when he died. He was instrumental in actually rekindling a lot of local interest, in Japan, in their own ancient culture right as the country was looking to modernize.

It’s all about loops, in a way—it’s all about circles. It’s fascinating how Yeats’s play—which was kind of a misappropriation, mistranslation, of an ancient tradition—is now being performed in Japan, by very, very traditional Noh theater groups. It’s become, in a weird way, part of the canon of Noh theater. That’s a really interesting turnaround—it’s really come full circle. I think what Yeats achieved was his foolish and bold reinvention of this thing gave an occasion for Japanese artists to then rethink it themselves. There was a sense of that At the Hawk’s Well was used sporadically throughout the twentieth century as a way to rethink the Noh tradition.

What about the other historical works in the show? I know you sourced different modernist pieces for the occasion. How did those play into this narrative we’re talking about?

They’re all things from this moment in 1916. I’m not really a literary person, so a lot of my route into this moment was through visual art. Actually, it happens that Ezra Pound was extremely instrumental in a lot of what was happening within the visual arts of London at that moment. He was heavily involved with the Vorticist movement, for example, which is how he hooked up with Gaudier-Brzeska. It was a very small but very connected world that formed between literature and visual arts. Because we’re not actually going to perform the play, I suppose the idea was that the backstory of the whole thing—the frame, the context—would be fleshed out in the form of this historical presentation.

There’s some extremely rare and special Noh masks that have come from various collections. There’s a Constantin Brancusi, which is a portrait of Nancy Cunard, the hostess of the first performance and a Gaudier-Brzeska sculpture as well. There’s some works by Ezra Pound’s then wife, Dorothy Shakespear. There’s also Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill , which was perhaps the Vorticist masterpiece but also the point of the movement’s unraveling, in relation to what was playing out in the trenches of France in the First World War. All these pieces are an attempt to frame the context of the 1916 moment.

Epstein's

Rock Drill

and prepatory drawings at the Japan Society. Photo by Richard Goodbody

Epstein's

Rock Drill

and prepatory drawings at the Japan Society. Photo by Richard Goodbody

In almost every article about your work, you’re referred to at some point as a storyteller. How important is the background research you do to understanding your work? It’s essentially the only thing we’ve been talking about, and it strikes me as crucial to getting a handle on what’s going on here. How do you think about educating your audience?

This is a very particular case, because we’re dealing with the artifacts and outcomes of staging a play, which is only available to the audience here in the form of a text. I suppose the whole project is about this tussle that you’re talking about between research and the manifestation of that research in artworks. In a way, that’s what’s going in the play between the character that plays me and the character that plays the theater maker: a struggle between the desire to tell the backstory of this event—the staging of this play in 1916—and the staging of the new play.

This is absolutely a discussion that I’m having the whole time in my work: how you bring the research—I don’t even like to use the word—the backstories, the context, onboard. I’ve come up with many solutions for doing that over the years, and staging a play is, I guess, the latest of those solutions. In a way, the play is very overtly about that problem. Making films has been another way to do that—the Project for a Masquerade that I’ve been talking about a lot is heavy with information. It’s a 30 minute long film, but it’s very dense with layers and stories and anecdotes, all held together by these incredible objects that Yasuo made. He’s the glue that holds that whole thing together—he’s the only reason that these crazy constellation of stories can hold water.

It seems to me this is an issue that’s endemic to conceptual art in general. Much of the best-known examples basically require an explanatory back-and-forth between the artist and audience in order to become legible: an interview, a wall text, an explanation within the artwork.

For me, it’s also about how objects can activate storytelling in different ways, and how they can hold stories in their orbit. What’s clear is, if the objects aren’t right, the rest doesn’t function.

How so?

There has to be something that holds the audience. When you walk into this exhibition, it’s a demanding situation for somebody who has no great knowledge of Yeats or Modernism or Noh theater or whatever—there’s a lot stuff to deal with and take on. I think by working very specifically on the form of things—by making these masks, in themselves incredibly captivating, haunting things, and these trees that they stand on, which are almost figures but also relate to the last trees of the first World War, or to a forest, or a kind of fairy wood of Irish folklore or what have you, and the quality of the choreography by Javier or the music by Josh—you create a very rich experience. That’s what allows you to go that little extra step, which allows you to draw people into the narratives.

All of those objects are generated from thinking about those narratives. It’s always a tussle . I’m still learning how to do it, I think. It’s evolving—it’s always evolving—and I suppose making a play and curating an historical show are just the latest attempts to try and make that work.