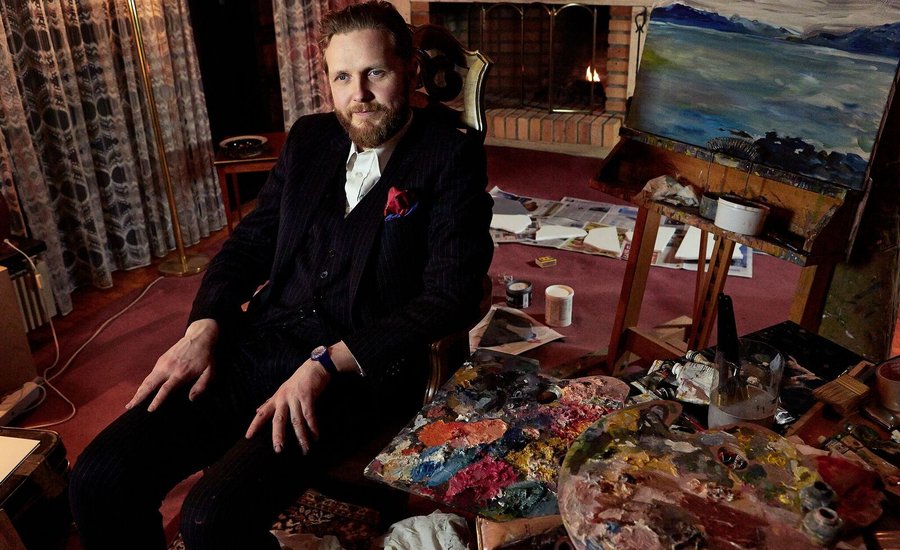

When people say they love Ragnar Kjartansson’s work, take a moment to look into their starry eyes. They mean it literally. There’s just something about the Icelandic performance dynamo’s joyous, anarchic, soulful, uproarious art that shakes you by the shoulder and opens your eyes to the lovely, ridiculously messy possibilities of life—a topic he has explored though such feats as singing a Mozart aria for 12 hours straight and taking children on a chatty tour of a graveyard, dressed as Death. Now, Kjartansson’s expansive spread of art is getting its due in the United States, with a new retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum (toured there from London’s Barbican) and a pair of shows opening at Luhring Augustine’s New York spaces on November 5.

Chiefly known for his moving videos and performative pieces, such as a six-hour looped rendition of the song “Sorrow” that he coaxed out of indie band the National, Kjartansson has also immersed himself in painting since giving himself a crash course in the medium during the 2009 Venice Biennale, where he turned the Icelandic pavilion into a studio where he painted portraits of a beer-drinking, Spedo-clad friend over the course of the exhibition. Now, his new gallery showing will present a group of paintings that he made in the West Bank—marking a new phase of political engagement in his work.

To mark the occasion, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein spoke to Kjartansson about his new body of painting, the deeply humanistic themes of his work, and what his wife means when she describes his artistic approach as “warm nihilism.”

In building anticipation for your show, the Hirshhorn is promoting you as “one of the most celebrated performance artists,” whose work is “at the cutting edge of performance art.” Do you think of yourself as a performance artist? What do you make of those terms?

It’s almost funny when you fall into the PR machine. There was that slogan on the sign for the Barbican show: “One of the most celebrated performance artists anywhere.” And I wanted to do a little graffiti so it would say, “One of the most celibate performance artists.” [Laughs] That would have been pretty good. But, I’m kind of fine with “performance artist.” You know, it’s kind of whatever. Because performance art is where I started out from—it’s the harbor I sailed the ship from. And “performance art” is a damn open term. It’s a fun term to twist and play around with. So, yeah, I can accept that, definitely.

You also come from a family of performers, so one could say the stage is in your blood. But, interestingly, over the course of the last few years—since your magical “Bliss” in 2011—you seem to have segued from the part of a performer to one of director-producer, assembling scenarios that you then set in motion on repeat. What inspired the change?

The interest shifts. I think I’ve done a lot of performance work just because of the kick of performing, and then, with some of the recent works, what I’m interested in has shifted. So, I always try to do what’s interesting. I still do performance work, but it’s hard for me to define it. If I’m performing in a piece, I don’t sense my presence in it so much. I’m there because I’m needed there as one of the elements to do the piece. When the work does not want me to be an element in it, I just don’t use me. When I’m needed, I’m always up for the call, when it comes to myself.

[Laughs] You’re your own director, star, agent, and casting director, all in one. One benefit of a theatrical performance is that it enacted live, in real time, but can be repeated again and again for different audiences. In many of your pieces, you’ve opted to repeat the same performance over and over again for the same audience, creating a looping, durational experience. Your videos, of course, are also shown on a loop. As a result, the vast majority of your work, either on video or live, occupies a funny space between something static—like a sculpture—and vivant. What draws you so much to this format? And how do you think of what you’re making?

I mainly look at it like I’m working with clichés. You know, the loop has been around so much for so long in art and also in all kinds of human activity. It’s naturally very up for grabs to use it as a medium, just like someone uses drawing as a medium. And I feel it’s a powerful medium to use in making what is performative become more static and lose its novelty. I love the performative, but I’m not so interested in performing itself in my own work. I’m a bit of a situationist, and you can always use those tools to emphasize the situation that something is about.

Are there any other kinds of artworks you look back to, or other art forms that you see as being in the same vein as your looping cliché investigations?

I remember in art school being very interested in the idea of tableau vivant, which is an old art form where you had these theater pieces that were just static. I was just enchanted by that. So I think just the idea of tableau vivant was a very big influence. Then when it comes to paintings and sculptures, you can see them as tools where you can just investigate something forever within the cycle of a surface. I’m starting to bullshit, I guess.

It’s funny, because the tableau vivant is such an antique format, but then again the notion of the loop, which is a slight temporal tweak to the tableau vivant, is technologically omnipresent these days. If you go on social media, loops are all over the place, from GIFs to Instagram or Vine videos. It’s viral, and very distracting.

It’s true, they are everywhere, and they’re all around us. I look at them and I’m amused by them, like we all should be. Being of this generation, the loop is just one of the things around you. It started out when I was in music—we used the loop so much doing computer-mixed music around the turn of the century. Now it’s being used everywhere in technology. And I think that certainly has an influence. I’m always trying to be of my time in my work. My mantra is the Kanye West phrase from “The Life of Pablo”: “I’m living in the 21st century, doing something mean to it.” You know, you can’t escape your time, and I don’t want to escape my time. It’s ridiculous—we’re living in such interesting times.

So, are you going to start a clothing line now too, like Kanye?

[Laughs] Yeah, that’s the plan. Winged shoes, baby, winged shoes.

Speaking of fashion, you have a piece in your new Hirshhorn show that has been getting quite a bit of attention: Woman in E. It consists of a female performer, dressed in a resplendent gold dress and standing on a rotating gold dais in a gold-draped enclosure, and she’s strumming the E minor chord of a white-and-gold Telecaster over and over. The overall effect is a bit David Lynch-goes-to-Valhalla. What is the genesis of the Woman in E?

Woman in E started out as a piece I did for MOCAD in Detroit in the beginning of the year. I got the idea because I was just looking at the space—it looked like this old car showroom—and I was thinking about Detroit, suddenly, voop, this piece came out. I thought, “Ah, this piece has to happen”—the idea of this golden lamé and this rotating woman on a pedestal, kind of like in an auto show, and this play on being objectified and empowered at the same time. You know, there’s a lot of weird ethical stuff coming together.

It started when I had been thinking a lot about equestrian sculptures, which are these ultimate Western-culture thing, where there’s a man on a horse in a city center. I thought this would be a kind of a modern equestrian sculpture for Detroit, with this lady with an electric guitar resonating all my ideas of American music and Motown and whatnot. Then, somehow, when we were discussing the Hirshhorn show, it just made so much sense to do that piece there too, on the National Mall where you’re surrounded by a lot of powerful monumental work. In my world, to have this monumental performance work rotating within the architecture of the Hirshhorn, it somehow made perfect sense.

Why is she playing the E chord, of all chords?

I just remember when I was learning guitar, and learning the chords—suddenly, when I learned E minor, it was the first time it sounded like music. E minor is the ultimate sad, beautiful chord. It creates a kind of instant melancholia. I remember when showing it in Detroit, Martha from Martha and the Vandellas came, and she liked the piece, but she said, “You got the chord all wrong, boy! It should be B flat.” But we tried it with B flat the next day and it didn’t work. It had to be E minor—it’s a Woman in E.

One could say that kind of beautiful, E-minor melancholia is the essential note of all your art—that you work in that key. Often, your loops give off a mixed sense of futility, optimism, resignation, and romanticism that grows more pronounced as they go on. For me, the most affecting of your works is Me and My Mother, which is a recurring scene of your mother spitting in your face over and over again—only it’s at the same time a linear piece, because you film it every year, so it’s a portrait of you and your mother as time go by, like a flip book. It’s beautiful in part because of its sad wisdom, that time, at least as we experience it in our lifetimes, is not a loop but a finite linear progression.

Yes, but it’s also the first piece where I was working with the idea of a loop. I started that piece because the loop occurred to me, where there’s no beginning and no end, just us being there in the middle. And I’ve done a lot of pieces that are linear, but they’re always about repetition. Like the one you may have seen at the Palais de Tokyo, where I was trying to make this stupid cinematic painting of my favorite novel [World Light by Icelandic Nobel Prize winner Halldór Laxness], where we’re just play-acting the scenes in the novel but it’s a total cacophony.

It’s a piece where I’m playing with the narrative and it totally becomes absolutely fucked up, which I think is very important. I’ve played with narrative a lot, but I tend to play with it instead of actually using it. This piece [Me and My Mother] always has a very special place for me. It’s sort of like my first piece, and it’s a piece that will always continue while we’re both alive.

Time is such a key component to your work in a way that’s unusual, because after a while of watching a scene repeat and repeat the audience can’t help but start thinking about time as a concept. In a way, your work is often about time, like the way that your Scenes From Western Culture slowly repeat cliché experiences—a dinner in a fancy French restaurant, a barn on fire, a children’s party for a rich family—over and over again. How do you think of time in relation to the art you make?

I look at time as almost like a layer in paintings. Sometimes you need time for the situation to somehow become more intense. And sometimes you don’t really need time—sometimes you just need a quick [gasping sound], like a bold stroke in a painting. With those Scenes FromWestern Culture, the time is really needed to make them become… [pause] I don’t know. I could have had them on really short loops, like we were talking about with the Vine videos. But there’s something about longer time limits, and always I find steadiness in time fascinating. To just do the same thing for a long time… I must confess, I’m just totally fascinated by it, and the way it intensifies a situation. Time is an intensifier, I guess.

It seems like sometimes that you’re looking at things from a kind of ancient, glacial perspective. Scenes from Western Culture really drove that home for me, where you’re watching something that’s a cliché—this canned moment of going to a French restaurant, for instance—and then gradually you see it as more than just the act of going to a restaurant but as a little ritualized phenomenon that we all go through on special occasions, and then you start to see this kind of affluent display as a moment in the span of Western culture, and then Western culture itself in the span of a larger history. It’s almost like a miniaturizing effect. In fact, one can read it as a celebration of the transience of Western culture as much as a celebration of the culture itself.

I guess it’s like that with everything I work with—I always see things both ways. I really love Western culture, and then I’m also scared of it, like we all are, and see it as choking everything. It’s a double-sided thing, absolutely. It’s both a praise and a critique, and I’m always interested in that grey area. I think that’s where most artists want to live, in the slippery gray area. It’s where things are interesting, where they’re not black-and-white. In religious terms, you could call it Satan’s area, because it’s always slippery, you know. And there’s no truth in it, but there’s this weird aesthetic or poetic truth, which is always what an artist, or just somebody who likes art, lives by.

It’s like a cheerful kind of weltschmerz.

Yeah. The term that my wife uses to describe it is a kind of warm nihilism.

Warm nihilism. [laughs]

Yeah. [Laughs] Scenes From Western Culture is a very nihilistic piece, in many ways.

On that note, I think it’s fascinating that your show at the Barbican in London opened just a few weeks after the Brexit vote, which is now putting a crack in the safeguards against European war, and now you’re doing a show in Washington, D.C., during this kind of climactic, terrifying American election where one can see a similar kind of cracking in the foundation.

Yeah! There’s really a cracking in the foundation. I think what’s happening in America is way more scary than Brexit, because it could be like a threat to civilization, you know! Like, seriously! I just find politics absolutely fascinating. They are like a silver lining going through all of my work. The political tensions are what really builds up a reality. It doesn’t matter what you do—an artwork is always political. Our world is just full of tension these days. Really scary stuff. Because, you know, people are becoming forgetful of what happened in the last century, and it’s just the human condition to go back into total stupidity.

You often look back to earlier historical periods in your work, to the viking era, say, or the Enlightenment. People often make the comparison, but the present moment feels like the beginning of the insane latter chapters of the Roman Empire, where you have bizarre emperors, decadent pleasure barges, and barbarians coming to set fire to everything. As an artist, how do you view this broader sweep of history?

Being a history person, I always feel that’s also the soothing part about it—that history is always a constant catastrophe. And we are in one of those catastrophes. It’s only the ‘90s that wasn’t a catastrophe, almost [laughs]. I also just love how history and the times are like a guitar amplifier to a note that you play.

One of my favorite artists is Jean-Antoine Watteau, the French painter, who did these lovely, lovely paintings that are just so telling of the times and everything that was wrong about them, and also about how that time is ending, with the revolutions on the horizon. You just sense it all in these paintings. Probably because they are so subtle, they somehow become a mirror. Everything that’s happening around us is terrifying and fascinating at the same time. I think that always becomes an element in my works.

One of the most uplifting things about your work is that there’s often a tendency toward catharsis, that something is being wrestled with until it changes. A song is sad, and then, through repetition, it becomes triumphant. It’s a very appealing kind of thing for an audience to go through, which might be one reason why your work is so widely cherished. There’s also a sort of secular religiosity to this manner of experience, which reminds me of when thousands of people made a pilgrimage to sit opposite Marina Abramovic during her The Artist Is Present show, look into her eyes, and cry. Do you see your work as being in this vein of cathartic experience?

Yeah, it makes sense. I mean, I once had a talk with Ulay about this. He was saying that he was studying religious ceremonies to find a way to do humanistic ceremonies. But I think that catharsis is… I kind of shy a bit away from calling it that, because that’s too pompous or something like that. But that element is surely there.

Art like this offers a very humanistic approach to satisfying a deeper need that many people have.

Yeah, and when you look at history, these people who believed in humanistic things and pleasure are the ones who have done the least harm in the world. It’s always the ones who are looking for some total truth who are the destroyers. Those who are really building up, they tend to destroy.

I think it has a lot to do with the fact that I was very much raised up in religion. My mother is super religious, and I was very religious as a kid, all through my teenage years. I was both in Lutheran youth groups and also a Catholic altar boy at the same time. But then I realized that these are rituals to soothe the soul, and that what I found more soothing was the humanistic elements of religion, which is good music and sometimes good literature.

Like, when you’re reading the Bible you sometimes get some really, really juicy good stuff, mainly, of course, in the Old Testament. There are like gorgeous artworks in the Old Testament. It’s funny, talking about this humanistic thing—I was also just learning about Frederick the Great, who was an openly atheist monarch. He was gay, and he only believed in art. I think it’s so cool.

So that’s kind of ruler you would like to have?

No, because then of course you come back to the gray area, because he was violent and just stupid about many things also. So, there you go.

Considering your interest in history, is there another era that you feel naturally sympathetic with—that you would prefer to the present day?

No. There’s no period I’m more sympathetic with, but then, again and again in our conversation, we come back to an epicenter: the Rococo. The time of pleasure. I just find that a very interesting era. But there’s no time I would rather live in, or anything like that. I’m just so freaking relieved to live in my time. I think it’s a super exciting time in every, every aspect.

Where you don’t have to die from every disease….

Where you don’t have to die from every disease and the patriarchy is a little bit less effective than it was in the old days. I mean, we live in a time of women’s liberation, which makes life so much more interesting. I just can’t imagine that we lived in a world where women weren’t allowed to be educated. It’s just such a nightmare.

Your show just left England, a country now being led by a woman, and it’s come to the United States, which may be led by a woman soon too.

Yeah, hopefully. Hopefully, hopefully, hopefully, hopefully. I’m getting more and more scared that it’s not going to happen.

I keep on thinking that maybe at some point the artistic community, or the creative community, or somebody, is going to unveil something incredibly extravagant and persuasive to persuade people to reject Donald Trump. Like, that Beyonce and Tom Hanks have convened everyone somewhere to create something epic.

[Laughs] Then let’s do something like that, god damn it! Wake up!

What are we supposed to do at a time like this?

Yeah, because it’s still so frighteningly close to happening. That total stupidity and ignorance would take over America. And… brr, I don’t know. I think people are just kind of dumbstruck. I just found some articles about my godmother from the early ‘30s in which people are like, “Wow, this guy in Germany is really behaving in a crazy way!” You see how the Nazis really started out as a joke, and then they just got power. I’m not saying he’s a Nazi, but who knows? It’s super scary. When you preach hate, it’s just going to end in one way. It’s just going to end in war. I think this guy has way too little knowledge to have all this power.

In London we had Wolfgang Tillmans’s effort to campaign against Brexit through art, which was this beautiful gesture and now, in retrospect, such an idealistic kind of thing. Is that even a place where art can be effective? Or does art have more to do with solace, the ways to live a good life, and things like that?

Now, for me, I think art can of course deal with everything, and I’m very political in my personal life. But I kind of like my art to deal more with the non-idealistic things. I want my art to be satanic. But, of course, art can try and do anything. We all try to use our position to do something political. For the last election in Iceland, I used that art form I use a lot, which is to repeat stuff. I just posted myself on the main square of Reykjavik with a guitar for like six or seven hours, singing, “Don’t vote for the nationalists. Don’t vote for the conservatives. And if you do, we will all go to hell.” [Laughs]

And did it work?

No, it really did not work. [Laughs] But I didn’t look at it as a piece of art, I just looked at it as a separate act.

It’s great that you did that in a public space and not an art context, because if you’re trying to persuade people who have opposing views that’s not really where you find the right clientele.

Oh yeah, it’s totally preaching to the choir. That’s always the thing, because you usually have to be a bit of a humanist to be turned on to art, and usually those people have thought-through political views.

To jump to another topic in a different branch of the political universe, you also have a very interesting pair of shows opening at Luhring Augustine next month, which focuses mainly on a new group of paintings that you made en plein air in the West Bank. To some of your fans, who know you best for your performance-based work, the medium and subject matter might be surprising. Can you talk about how that body of work came about?

I’m always doing that stuff [painting and drawing], too. It’s kind of like this other side of me or something like that. But I was asked to do a show at the CCA in Tel Aviv, so I made paintings of the Israeli settlements in the West Bank. So they’re very problematic paintings of nice houses that are loaded with all kinds of questions. Those are the most recent object-like things I’ve done, but it was kind of where painting and performance art meet.

It was a strange thing to go to the settlements every morning in a van with Ingibjörg [Kjartansson’s wife] and our Israeli friend and driver—to go through the gate like, “Hey, I’m going to paint the house here.” And then this whole situation happens when you’re painting outside, with the people who walk by and watch what you’re doing. And here I was dressed in a white shirt and linen trousers and a hat, just a classic painter’s outfit. So the objects are a part, almost like a documentation, of a performance, which is pretty often the case for me.

What made you interested in doing a body of work about the West Bank, which is such a fantastically complex political quandary halfway around the world from your home?

I had this question from a lot of people in Israel, but it feels like Israel is with us every day in the news here in Iceland. It’s like a situation that’s always with you, and it’s so interesting to just go straight into it and live it for yourself and just be there, and then go do the most innocent thing on earth, which is make oil-on-canvas paintings of houses.

But then these houses are just very loaded with a lot of moral questions. Actually, it’s a piece that is so politically loaded in all directions. That’s what I like about it. If you’re pro-Israel or pro-Palestine, either way, you’ll really hate this piece. Which I think is important.

Israel is on the news in Iceland all the time?

Yeah, absolutely. Isn’t it on the television everywhere, on the news?

Not in the United States that much anymore, at least this year.

[Laughs] Yeah, totally. Your country kind of broke up with Israel in so many ways. On the other hand, my mother is a very firm Zionist.

Really?

Yeah. And everybody in Iceland of my kind sister’s generation was going to work on a Kibbutz.

Wow.

There’s a lot of connections. It has always felt like a very close country. So it was a very interesting artistic situation to go into, if you know what I mean.

It sounds like a kind of less extreme, more fanciful version of what war artists like Steve Mumford do, going to the front lines and making art from what they see.

But what also interested me is the fact that it isn’t really extreme. I find that more intriguing, when it comes to Watteau part, you know, to go to these gated communities and just paint nice houses. But those houses are just loaded with war. It’s not like going into a war zone, dealing with black-and-white truths—it’s the complicated zone. Once again, it’s the gray area. And you can’t imagine how much fun it was to be in like the scariest settlement, and leave the settlement, and listen to hip hop in the car, like whew.

So, where do you go from here? What are you working on now?

I’m actually in a bit of a tabula rasa thing now. Ideas are slowly popping up in my head, but I don’t really know what I’m working on now. Which is a good feeling. [Laughs] There’s like a lot of stuff, but nothing that feels really concrete.

That sounds like a nice place to be.

But then again, I’m always scared, which is good. [Laughs.]

That’s good?

Yeah, I’m scared shitless, which is very important, I think. Weirdly it gives you bravery, to be scared.