It’s not too surprising that the New Museum has selected Alex Gartenfeld to organize its 2018 Triennial. The 29-year-old curator and critic has had his finger on the pulse since he first began putting together exhibitions with his roommate—the curator Piper Marshall— in their tiny Chinatown walk-up apartment, where they showed artists like AIDS-3D and Tobias Kasper in 2009. (This was just a year after Gartenfeld graduated from Columbia University .)

Since then, Gartenfeld has been an editor at Art and America and Interview, and interim director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami . Now, Gartenfeld spends his days as the deputy director and chief curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami , working with emerging talents alongside established figures like Ida Applebroog , Thomas Bayrle , John Miller , and Laura Lima .

Since the beginning of his career, painting has been a central component of both his critical and curatorial work, and it's something he knows about intimately—after all, he spent hours sitting for a portrait by the up-and-coming conceptual realist Matthew Watson .

Now, as the latest in our series of interviews around Phaidon 's new Vitamin P3 compendium of contemporary painting , Artspace’s Loney Abrams spoke with the ambitious curator—and P3 nominator—about the political and economic dimensions of abstract painting, the pre-digital canvases of Thomas Bayrle , and what he's discovering about the medium's direction while assembling the 2018 Triennial with fellow curator Gary Carrion-Murayari .

What can you tell me about your plans for the 2018 New Museum Triennial?

I have to give you the perfect caveat that we’re a year away from announcing any theme. That is a big caveat. So, I’m not able to talk specifically about any artist that we are researching or any particular theme. However, I can say that, as part of our broader research, we are considering a number of traditions in painting, and how artists today are dealing with the legacy as well as the economic and political dimensions of painting.

By “economic dimensions” do you mean in terms of the market, in an art-world context, or something else?

Well, painting stands out in a lot of ways, because it has the most proximity to the market, so it can represent the cultural value of art better than any other medium. Of course, economies are different all around the world, so for a painting to engage with history and economics in the West is quite different than it would be in currents inside the Caribbean, where the market doesn’t exist the way we know it in the West. That's probably overly broad, but it is what it is.

Can you tell me about an exhibition you've recently curated that involves the economic and political dimensions of painting?

So, it might be paradoxical for John Miller, an artist who is working in the tradition of conceptualism, to focus on painting. But painting is one of his favorite media, and it’s actually his first medium—the earliest painting we had in the show was from 1982. For John, and for other artists of his generation, painting is the medium most able to create a realism, and by that I mean able to look like nature or reality while also being clear that it is a representation—and that that representation has a political and economic undercurrent.

For instance, John’s brown impasto work—which are executed in various media, but all using this thick, brown impasto executed in a series of brushstrokes—are dealing with generations of painters for whom the gestural brushstroke communicated a certain type of freedom, and the possibilities for that freedom today. But he was also dealing with a challenge to the interpretation of a painting as something beautiful and valuable. Hence, he uses strokes of brown impasto that look like nothing so much as a smear of shit.

John Miller's

Untitled

(1990)

John Miller's

Untitled

(1990)

When you talk about painting's ability to engage with political and economic concerns, the way it's exceptionally well suited to express realism, you don’t see that as being limited to representational painting? In your mind, can abstract painting be equally realist or political?

Let me think about how to put this. Absolutely. For instance, one of the artists who I nominated for the Vitamin P3 book is Ryan Sullivan , and Ryan is somebody whose work could comfortably be categorized as abstract, although it can appear to represent surreal landscapes, or a detail of a material. But because of the way that Ryan thinks about historical tropes in paintings—the gesture, the mark in American abstraction—and the way that he combines it with a really unique mode of performing that gesture, I think it functions as a critique.

Ryan Sullivan's

Untitled

(2014)

Ryan Sullivan's

Untitled

(2014)

Ryan Sullivan has been described as intentionally referencing digital photography and aerial photography. Do you think that, in some cases, painters are struggling to make painting relevant in the Information Age? In other words, do they need to contextualize it within something beyond the medium?

So, at the risk of constant self-promotion, I commissioned an interview between Ryan and Laura Owens for Ryan’s book, which is due this fall, and a big chunk of that interview is dedicated to each of their relationships to painting and photography. For instance, Laura has created a number of installations where the audience’s movement is required to, quote-unquote, complete the picture. On the other hand, Ryan’s work possesses a detail that is so high-definition that it seems to be functioning as photography, even though it's not. Also one of the many demands that his paintings make is that the viewer encounters them in person, so that the experience is different from the experience of viewing the painting through the medium of photography.

I’ve actually never seen his work in person, but his works are very convincing as photographs when viewed online, possibly because they're flattened when they become documentation photos. Although this may not be ideal, probably 95 percent of the art that I see—and that most people probably see—is mediated through the computer screen as a jpeg. How do you think painting fits in with contemporary image culture? When does a painting become an image beyond being a painting? Or does it?

I think the answer to that is complex, and I think that painting needs to constantly prove that it's different from other forms of image production in order to continue to have cultural value. That said, I think that the tradition of painting, and what it means in a variety of contexts and histories, is so much a part of our culture that I think it has a special aura that keeps it relevant and in dialog with contemporary issues.

Shifting gears a bit, I came across a portrait that Matthew Watson painted of you.

Oh, yeah, that’s fun.

Matthew Watson's

A.G., W.B., and S.A.

(2013)

Matthew Watson's

A.G., W.B., and S.A.

(2013)

Matthew Watson is a particularly complex kind of portraitist—instead of simply capturing his sitter's likeness, he also includes highly specific artworks, objects, and other elements that tell a story about the way the subject fits into the economic and social milieu of the art world. In other words, it's highly conceptual portraiture. What do you think the role of portraiture is in contemporary painting now?

Well, I couldn’t totalize the entire field. I will say I commissioned that Matthew Watson painting for Artissima’s special section, “Present Future,” in 2013, and, knowing Matthew’s practice, I wasn’t surprised that he asked to paint my portrait. The portrait was executed in the home of a collector who has been and continues to be a significant supporter of my curatorial practice. I’m painted alongside a work by Wallace Berman, and on my other side is a sculpture by Sam Anderson, an amazing artist who has a show forthcoming at SculptureCenter and also at the Kölnischer Kunstverein [in Cologne].

The collectors actually subsequently bought the work, so now it’s actually hanging right next to where it was painted. For an artist like Matthew Watson, portraiture is such a rich field because it connects people through power relations that are emphasized through the picture, instead of being repressed. And I don’t mean power relations necessarily in a negative way—I mean it in a really positive and rich way, in this case especially. But Matthew’s work is inscribed with a genealogy of artwork and people, representing a certain type of community. He’s done other portraits of people like Kara Walker , Nicolás Guagnini , and, incidentally, John Miller — artists and colleagues who have had a crucial role in his life, but who also represent a certain set of values in art production.

Since the days of the Renaissance, a comissioned portrait has always been intrinsically illustrative of power relations. But it seems like what's fresh about Matthew Watson is that he's calling attention to this dynamic, making it transparent.

Of course, portraiture has a millennium-old relationship between the commissioner and the artist, as you’re very right to point out. In that body of work, Matthew adds significant complexity to the role of the painting and the artist in creating that representation.

I would like to ask you about some of the other P3 artists you nominated. We already talked about Ryan Sullivan, but what other painters did you nominate for P3?

Elizabeth Neel —what a fantastic, under-recognized artist. And Jana Euler ! I’d like to say something about Elizabeth becaues she’s so great, but I can’t think of something off the top of my head that would be so accurate. I mean, it’s banal, but she blurs abstraction and figuration—but nobody wants to hear that. Sorry I’m not quick-witted enough. But I will say that right now I'm most excited about two artists from Miami—Tomm El Saieh and Diego Singh.

Elizabeth Neel's

Response to the Tide

(2015) is available on Artspace for $38,000

Elizabeth Neel's

Response to the Tide

(2015) is available on Artspace for $38,000

Is there anything else that you're excited about or working on that you want to mention?

An artist who’s not in P3 but uses painting in a way that is deeply engaged in technology is Thomas Bayrle , who we have an exhibition with this fall. Thomas comes out of the weaving tradition, which he learned before making art. Since the early ‘70s he's been creating these complex images, paintings, silkscreens, drawings, and collages, that have an... art, one could say; they have a pre-digital technique. Our exhibition will have about four decades of work, and viewers will see how complex form really can be.

What do you mean?

Thomas is very well known for making images of people or objects that are aggregated and stacked in a very dense way, so that they almost look woven together. The result is a microcosm representing multiple individuals, but also a superstructure or larger symbol. I think that his approach to image-making and conception of form says a lot about how painting can be in dialog with technology and, not to be overly grand, but also with the way society works. On the one hand, he illustrates a very democratic feel of the multiple, and, on the other, this very vertical idea of the symbol of… I’m trying not to use “fascism” here, but I guess that’s the only alternative. In other words, he illustrates the democratic means of the individual and the potential for totalitarian interpretation.

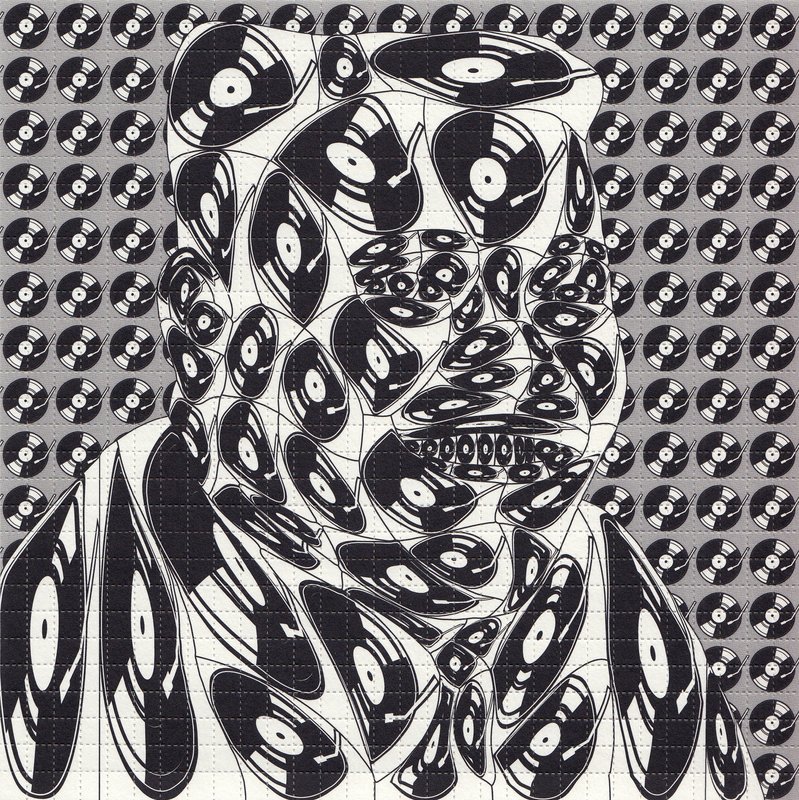

Thomas Bayrle's

Fats Domino

(2014) is available on Artspace for $244

Thomas Bayrle's

Fats Domino

(2014) is available on Artspace for $244

It’s interesting that you call it “pre-digital,” which it is, but at first glance it looks so very digital.

He actually calls it "pre-digital." I’m paraphrasing him, but the work on a surface level predicts the type of graphics that would become popular as a digital aesthetic. And that’s a really interesting phenomenon if you think about changes in German society, and changes to the economy, and the way artists and factory workers were working during that period, and how that lead to a revolution in technologies in the decades to come.