In an election season that has thus far proven divisive, disheartening, and almost giddily carnivalesque, many Americans on both sides of the aisle have been asking themselves how we got here and what, if anything, we can do to get out. For Freedoms—the nation’s first artist-run super PAC started by Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman currently operating out of its group show at Jack Shainman Gallery—doesn’t provide answers to these questions. Rather, its goal is to ask more questions, whatever they might be, in the hopes of sparking what their mission statement refers to as “new forms of critical discourse surrounding the upcoming 2016 presidential election.”

Fine artists have long attempted to frame their work in terms of their politics when it seems words are not enough, though the effects of these interventions, from Dada to Relational Aesthetics and beyond, have been primarily felt in the context of art history. Thomas and Gottesman’s decision to ground their project in one of the best-known examples of American propaganda—Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” series of oil paintings, themselves based on FDR’s famous "Four Freedoms" speech and later used to sell war bonds by the U.S. Department of the Treasury—reaches for an alternative mode of addressing an audience beyond the confines of the gallery or museum.

With an exhibition of works by some 48 artists and collectives, a schedule of events including talks, design workshops, and a voter registration table run by Trevor Paglen, and plans to convert the pieces in the show into billboard-ready adverts, For Freedoms seems poised to make good on its promise of generating conversation. Still, for citizens looking for a clearly articulated political goal or set of values, this probably isn’t the place. As Thomas says in the interview with Artspace’sDylan Kerr below, “I don’t necessarily agree with any of the artists in the show on every single issue, but that doesn’t mean I can’t embrace and support the raising of their voices.” Read on to find out how he’s hoping to do it.

For those of us who still don’t know, what exactly is a super PAC and how does your For Freedoms project work within that framework?

A super PAC is an express advocacy organization that is supposed to campaign on behalf of or against a candidate affecting a local, state, or national election. Our super PAC is different from most because it’s not overtly supporting any specific candidate or party. The idea is to try to put critical discourse into political discourse through an engagement with fine art. This is really a huge collaboration with about 100 other people and at least 50 other artists who are either part of the exhibit or working with us on different projects.

You mentioned that For Freedoms has no single platform or issue, but I wonder if there’s more to the story. What are the central concerns animating For Freedoms?

The central concern is freedom—what does freedom mean in the 21st century? That’s what we’re trying to bring to light. It’s supposed to be as unique as an individual art piece or an artist’s practice or an idea. Each of us has an investment and an interpretation of freedom, but we also have a stake in expanding or at least reinterpreting what it means to be free.

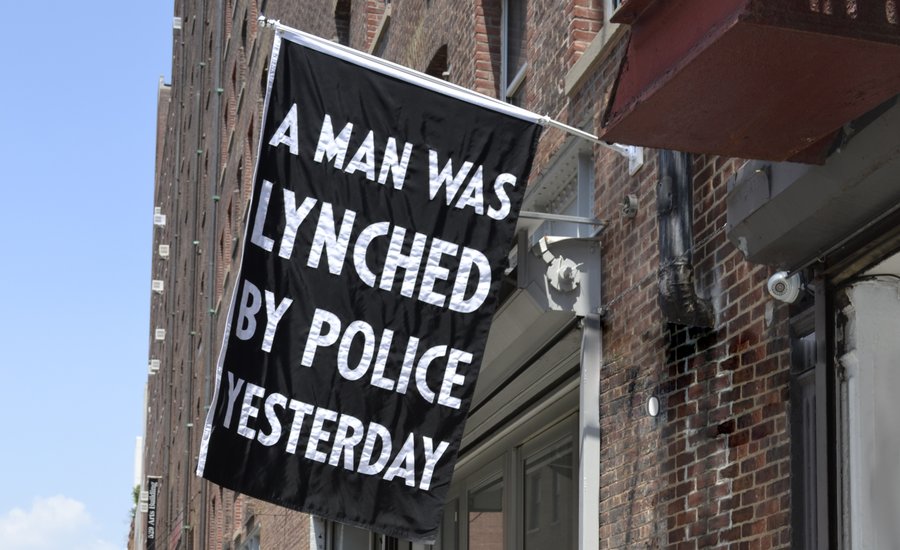

Installation shot at Jack Shainman's 20th Street location

Installation shot at Jack Shainman's 20th Street location

How do you see a traditional artwork—a painting, let’s say—as being able to further this conversation?

I think as artists we’re always dealing with the work of the future of our society. Although it may seem out of context or not make sense for the average person of their time, looking retrospectively you often realize that the work an artist is making is actually extremely on-point and dealing with really complicated and hard to articulate issues that couldn’t be expressed in the normal ways of advocacy, advertising, or traditional forms of education.

What are some examples of artists who have to done this in the past?

You can look to the Guerilla Girls, you can look at Jackson Pollock, you can look at Jasper Johns, you can look at Basquiat, or Jeff Koons, or Richard Prince, or Carrie Mae Weems.

It’s interesting that you bring up some of the figures you do. People like Jackson Pollock or Jeff Koons aren’t usually thought of as artists who have incited real-world political change.

Well, the C.I.A. used American art, especially Abstract Expressionism, as propaganda to show a literal expression of freedom against communism—it was all about these American values of unique, individual expression and the acceptance of that ideal. This is happening at the same time as the Beat movement and the Civil Rights movement, where there is a level of tension or clash that breaks down our traditional notions of culture.

There’s so many artists from the ‘80s like Felix Gonzalez-Torres who were dealing with LGBTQ issues or multiculturalism or gender inequality or wealth disparity that are only really starting to get attention in the mainstream today. Even this notion of post-race or post-black is something that only reached the mainstream 20 years after it was first discussed within the fine art context. There’s a precedent for artists reinterpreting what value is or what should be important for society. Society catches up over time and benefits from the way that artist’s expanded our thinking about these things.

Installation shot at Jack Shainman's 24th Street location

Installation shot at Jack Shainman's 24th Street location

Do you think there’s a direct connection between those concepts being presented in the art world and their later realization as a part of popular discourse? It seems to me that there are forces at work other than a brilliant artist bringing a certain idea or ideas to the fore.

It’s not a singular brilliant artist—it’s a community of artists that are in discussion with one another, communicating in ways that aren’t often legible to people who aren’t in their communities. Over time, it gets canonized—it’s put into museums and galleries and gets into people houses—and it disseminates into mainstream and eventually popular culture. By that time, it’s often so watered down that it’s not itself any more.

Is that how you think about your own For Freedoms project and the works that are on view in the gallery? Are we seeing the beginnings of conversations that will play out for the next several decades, or are their purposes more immediate?

Most political speech has something like a three-week shelf life, right? They’re designed to get your attention and make you feel a certain way, usually for or against something, and then disappear. On the other hand, art is expected to last a generation and have an impact for generations if not decades. You could argue that we’re playing the long game, but many of us are also talking about things that are happening right now. Unfortunately, those things may not change.

Why did you choose Norman Rockwell’s famous “Four Freedoms” series as the frame for this project?

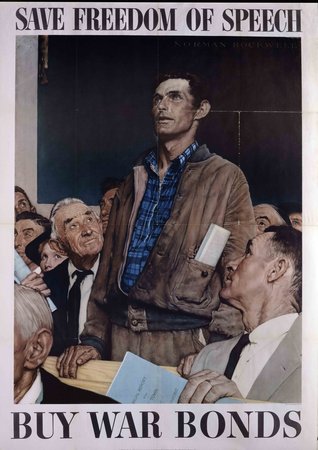

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms were an American artist-made work inspired by a political idea, and that work was appropriated by the U.S. government for other ideas. In the exhibition you’ll see these posters from the 1940s showing the Rockwell works that say “Printed by the Office of War Information.” They say things like “Save Freedom of Speech: Buy War Bonds” “Ours... to Fight For: Freedom From Want.” It’s pretty amazing.

It’s work that wasn’t originally commissioned by the government—it was first presented in the Saturday Evening Post, in popular culture, and then appropriated by the government for propaganda. The Four Freedoms themselves—freedom of speech, freedom from want, freedom of worship, and freedom from fear—are these universal ideas that I think are still important and relevant, but the representation of them in the 1940s was seemingly 99% white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. We live in a different America, so the question becomes what those four freedoms look like today.

Propaganda poster of Norman Rockwell's Freedom of Speech, 1943

Propaganda poster of Norman Rockwell's Freedom of Speech, 1943

In For Freedoms’s mission statement, you explicitly say that you’re founded to encourage “new forms of critical discourse surrounding the upcoming 2016 presidential election.” What kind of effects are you looking to have on this discourse?

We’re hoping to actually help create more discourse. Everything has become so dumbed down into this left or right, good or bad, Republican-Democrat, liberal-conservative, straight-gay, black-white, and I think there’s so much more at stake. If you come through the exhibit you’ll see that artists are speaking to so many different things.

What new modes of discourse or ideas are the works on view at the show bringing to the table?

I don’t know if they're new—it’s what art does. It’s fundamental to what artists’ practices are. I think what’s different is that it shows that the project doesn’t end at the gallery. This is fine art as political speech—that’s what’s new. Most artists’ work develops through critique, and in our society we’re actually deathly afraid of critique. Any critique in the political sphere is bad, whereas an artist is rarely afraid of being critiqued—that’s how our practices grow. We’re saying, “Can we take this conversation that we started in the gallery and start to put it out into the public?”

This is why we’re making ads and putting things out there in a variety of different ways. We’re doing actions and talks and talkbacks and performances.

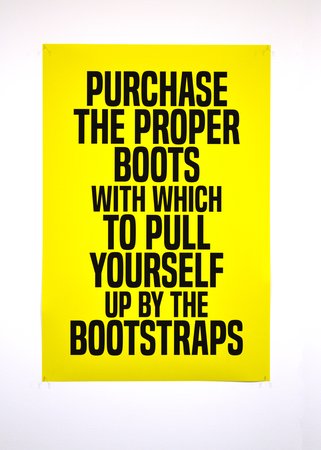

Kameelah Janan Rasheed's Purchase the Proper Boots With Which to Pull Yourself Up by the Bootstraps, 2014. ©Kameelah Janan Rasheed. Courtsey of Kameelah Janan Rasheed.

Kameelah Janan Rasheed's Purchase the Proper Boots With Which to Pull Yourself Up by the Bootstraps, 2014. ©Kameelah Janan Rasheed. Courtsey of Kameelah Janan Rasheed.

Part of the project is producing political imagery intended for a wider audience than the gallery-going public, in the form of billboards or ads—is that right?

We’re saying that the work that’s in the gallery is for a wide audience—it’s just that the audience will have to begin to feel welcome and realize that they can engage. We saw that happen with the Dread Scott piece after the events in Baton Rouge and Minneapolis.

I happened to be at the gallery as he was speaking, and there were about 20 people who came in the gallery just to see that work, and it’s not a new work. What does that mean? Some of the people told me, “We just flew in from New Jersey from Oakland, and my father told me that we had to come into the city to see this exhibition.” We were like, “Wow, that’s not normal.”

What role do collectors have to play in this process?

It would be interesting to speak to some of the collectors who have supported the project by donating to the PAC or helping to raise awareness through their own network. They’re already involved in politics and they’re also involved in art. How they’re choosing to do that I think is a really interesting story that I don’t think anyone has explored.

There is a group of people who have been major donors to the PAC, but they’re also doing fund-raisers and talking to the rest of their network, building partnerships with institutions. It’s pretty amazing that this was just an idea three months ago.

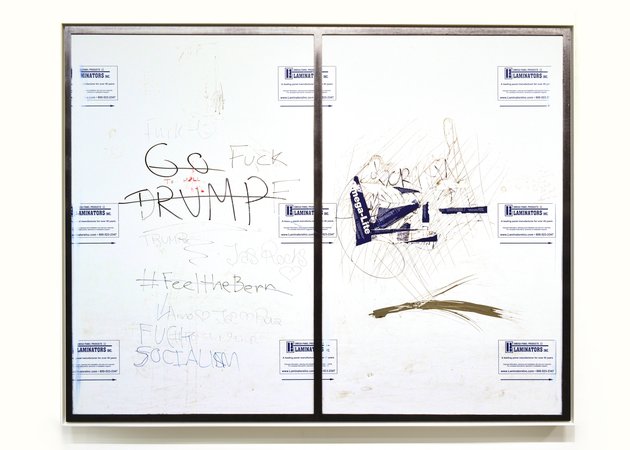

Wyatt Gallery's Go Trump, 2016

Wyatt Gallery's Go Trump, 2016

What do you think the future of this project is? Will it last beyond November?

That’s a good question. It’d be nice [laughs]. I’d like to believe that the future of the project is like the future of any artwork, because this project is an artwork. Maybe another artist will take this and turn it into something else—make their own super PAC, or create a 501c4, or take a totally different approach to creative action in politics.

What are some concrete, specific actions that an artist can undertake to catalyze political change?

I think they can just continue doing what they’re doing, but realize that they can frame it however they want. It doesn’t have to look like political speech to be political speech.

The reason that so many people in the art world are seen as liberal or open to ideas is that everyone would like to believe that they’re open to ideas. The reality is that there’s a diversity of ideas that people are dealing with. It may not be my issue or my taste in work, but that doesn’t make it not valuable as work.

That’s really what’s important, to recognize that in our society there can be different opinions about what the important issues are or what the value of something is, but at some base level we all need each other for this conversation to progress. There’s no new artworks being made, so to speak. It’s all building off of someone else’s ideas. In our political landscape, we need to have that same approach. We can’t be having conversations from 40 years ago today. That’s ridiculous.

I think a lot of people want us to choose a side or have something that looks like a political action—carrying signs or whatever. We’ll do that, and we did do that. We are registering people to vote with a piece by Trevor Paglen that has a postcard with a drone on it that says “Vote for War.” There’s also a layer in there. That’s not what I would say, that’s not my personal position, but that’s this specific artist’s position that’s forcing me to face my complicitness in things that I don’t believe in when I register to vote. That’s the thing—I don’t necessarily agree with any of the artists in the show on every single issue, but that doesn’t mean I can’t embrace and support the raising of their voices.