Flaka Haliti isn’t afraid to make bold statements with her artwork. Whether she’s smuggling bull testes into art galleries in her hometown of Pristina, interrogating the politics of European internationalism in the Kosovo Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, or sending up the art world in her solo booth at LISTE 2016, the young artist is always looking to score a strike against the powers-that-be.

Born in 1982 and raised in the Kosovar capital before decamping to Germany to continue her studies, Haliti is part of the generation that came of age in the midst of the bloody and still-controversial Kosovo War and the U.N.-controlled administration period that followed for almost a decade after. The country only officially declared their independence from Serbia in 2008.

It’s partly this tumultuous, divisive, and politicized context that informs Haliti’s art, but her purview extends beyond her birthplace. She’s currently living in Munich while she completes her PhD in Practice at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna, and her recent work is perhaps best seen in relation to the contemporary conflicts around immigration and nationalism in Europe, not just Kosovo. Her solo presentation at the Kosovo Pavilion last year, for instance, showed deliberately unspecified and abstracted border walls to point to the universality of these divisive structures.

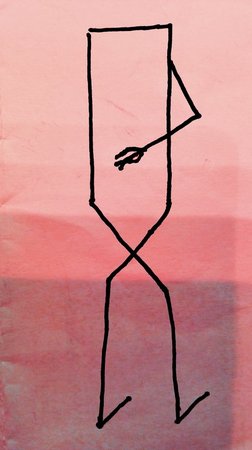

Indeed, her subjects are barriers of all kinds and techniques for crossing them. The aforementioned bovine reproductive organs were part of a gesture against the underrepresentation of female artists in Kosovo. Even her LISTE solo booth with Pristina-based gallery LambdaLambdaLambda challenges some deeply entrenched obstacles to entry, albeit of a very different kind. There, her shape shifting alter-ego Joe (also featured in her exclusive Artspace Edition, available here) wants to gain access to the international art market at any cost and takes on myriad fashionable forms to do so, stylistic consistency be damned.

Artspace’s Dylan Kerrspoke to the artist to find out more about how history and conflict have informed this pugnacious approach to art making.

What can you tell me about the work you’re showing with LambdaLambdaLambda at LISTE this year?

My solo booth in LISTE revolves around the fictional character that appears here and there in my work, always under the title Is it you, Joe?. It’s an ongoing series that I started to work on in 2015.

The alter ego, Joe, is used as a tool to respond to the framework of the rather fast capitalistic system where artists find themselves constantly in the loop of working fast and now, of following the market's requests to come up with a new product constantly. As such, Joe has the ability to act as a self-critical commodity. Joe is supposed to be a vehicle to simultaneously embrace this system and master it, either for me or for Joe. Joe plays my counterpart in my artistic production.

Haliti's solo booth with LambdaLambdaLambda at LISTE 2016

Haliti's solo booth with LambdaLambdaLambda at LISTE 2016

Your new Artspace Edition is also premiering at the fair—how does it fit in with the rest of the booth?

The Artspace Edition is another bodily extension of Joe, which contains a drawing of Joe as a liar figure, printed on transparent vinyl. With a limited edition of 15, each number has a different color since the main concept of Joe is that he never repeats himself.

LambdaLambdaLambda is really starting to make moves in the international art world, with booths in the major international alternative art fairs like NADA. Are Kosovo artists about to have their moment?

Well, I would say Kosovo artists had and still have their moment internationally. Now, with LambdaLambdaLambda focusing on the art market as the first commercial gallery that’s opened in Pristina, it’s definitely about time to create a bridge on the market level as well. I think LambdaLambdaLambda is already doing a great job in that direction.

Haliti's Artpsace Edition Is It You, Joe? (2016)

Haliti's Artpsace Edition Is It You, Joe? (2016)

What's the impact of LambdaLambdaLambda being the first commercial gallery? What do Kosovar artists think?

LamdaLamdaLamda was founded by the two Austrian curators Isabella Ritter and Katharina Schendl in January 2015. Although they have been welcomed there from the beginning, there’s no doubt that it took a while for it to become clear what role or missing link their program would fill in the existing system.

LLL says in their statement that the main core is to establish a model where artists can actually live from their art and not be merely dependent on sporadic support from either the state, NGOs, or institutions, which very often limit the ability to introduce alternatives models of working or functioning as an artist within society. As an artist from Kosovo that lives in Germany and who has been educated in and experiences the Western art system, it is quite important for me to collaborate and work closely with LLL by joining their exciting program and initiatives.

How would you characterize the art scene in Kosovo?

It’s small, yet very honest and always stimulated by young names coming up. It carries such an exciting energy, which makes everyone so optimistic—sometimes in cruel way.

What do you mean by that? Sounds interesting.

I’m referring to the cruel optimism that Lauren Berlant describes in her book of the same title. To roughly summarize, she writes that "optimism is cruel when the object/scene that ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain the expansive transformation...Optimism might not feel optimistic. Because optimism is ambitious, at any moment it might feel like anything, including nothing.”

I would say this describes the kind of mood and living condition you can easily find in the postwar countries, including Kosovo.

How does Munich compare to Pristina? And why Munich versus another German city like Berlin or Cologne?

Oh, many things are different—Munich and Pristina are simply incomparable. And it’s funny that everyone is asking THE question, “Why Munich?” I know—as young artist in my position it’s a surprising move, because Munich is still a very expensive place to work from.

But yes, after finishing my education in Städelschule I knew from the beginning I don't want to go to Berlin. I didn't like the idea that it has to be the next station for everyone. Plus, I get the feeling from my friends who live there that as the scene gets bigger, the daily routine is turning in to a real filter bubble—people have enough choices to avoid things they don't want to see, meet, or confront. They can create their own little community, which itself somehow becomes the commodity of their bubble.

Yes, Munich is smaller and less exciting—except the institutions, which have always been strong—but as small as it is, it makes it easier for people of different social classes, communities, and interests to clash. Nevertheless, what I don’t like about Munich is the mentality of thinking in a self-centered and local way, where each creative scene creates their own local heroes that can't be challenged because there is no real competition for them.

To go back to your question, I decided to be in Munich for private reasons, and as well as the fact that is closer to Vienna where I commute for my PhD in Practice program.

You don’t shy away from dealing with political issues in your work, albeit obliquely as in your installation for the Kosovo Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale. You’ve said that, “the aftermath of [the Kosovo war] has loads of elements that are a part of me” but that your work is “post-war,” in the sense that it “reacts to the current situation.” How does this situate you with your peers in the region? What are the current situations you’re reacting to?

Over the past few years I have been quite focused on the topic of my PhD, which is related to critical questions about the transnational versus national politics of representation in Kosovo. I’m attempting to produce a body of work that tends to open up an aesthetical and political space of reading the visual and the role the image plays in the body, culture, and politics under the phenomena of independence monitored by the European Union.

However, with the latest political events experienced within the Schengen zone, my work has aesthetically shifted slightly while trying to displace the question of origin, uprooting, places of belonging, and loss of possession. As an abstraction of these events I intend to create a counter-position from the twofold dilemma of what the image or the object has to offer.

Haliti's solo presentation Speculating on the Blue in the Kosovo Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale

Haliti's solo presentation Speculating on the Blue in the Kosovo Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale

What do people miss or not get about your work?

Not every work I do has a link to my background. I often see casual attempts to identify my work through a strictly local political discourse, which creates reductive political labels on how to perceive or read my practice.

So what’s the key to understanding what you’re doing?

Perhaps one could zoom in and zoom out more.

What’s next for you?

I have a few exhibitions coming up—one at INDEX Contemporary Art in Stockholm, a solo show in Gallery Rüdiger Schoettle Munich, a Lenbachhaus Museum group show in July, and another one later in September in Kunstverein Salzburg. Moreover, as a winner of the Villa Romana prize 2016, I will be enjoying working in Florence till the end of November.