The British artist Eddie Peake has been called a lot of things: “ the brightest of a new generation of London art stars ,” “ the art world’s latest enfant terrible ,” “ an old-fashioned craftsman ,” “ a playful agitator and instigator ,” and a “ self-confessed exhibitionist .” It’s a lot to live up to, but the soft-spoken 30-something seems to be taking the hubbub that's building around him in stride—and, if his substantial yet unpretentious works are any indication, with a fair bit of humor.

Peake first made a splash with his 2012 performance piece Touch, which premiered while he was still a student at London’s Royal Academy and featured 10 nude men competing in a soccer match. It’s a relatively straightforward concept, but the simple strangeness of the piece speaks to the issues that continue to inspire his work: physicality, juxtaposition, sweat, mass entertainment, and a kind of implicit sexiness.

While his paintings (often made with neon paint on mirrors coupled with slang- and euphemism-heavy text) sculptures (especially his scarfed silhouettes of bears) and videos (featuring some vaguely lizard-like characters) have achieved recognition of their own, his nudity-heavy performance pieces continue to catch the eye of critics and casual viewers alike.

His most successful exhibitions, like his 2015 project at the Barbican Center called “The Forever Loop,” combine all these media to delightful and sometimes delirious effect. Along the way, he’s collaborated on projects with everyone from the rapper Kendrick Lamar to his own sister in addition to co-hosting the gay club night Anal House Meltdown at venues in London.

For his latest project, he’s teaming up with London’s Counter Editions (along with seven other artists including Tracey Emin , David Shrigley , and more) to produce a limited-edition series of prints for the 2016 Rio Olympics . Artspace’s Dylan Kerr spoke to Peake to find out more about his abiding love for sports of all kinds, his predilection for pop-culture reference points, and why he thinks the exhibition may be the most important unsung art form.

Great Artworks Worthy of the Olympics featuring paul mccarthy, richard prince, jonas mekas, and more buy now

Let’s start with the piece you’re making for the

Counter Editions portfolio

. What’s the nature of this project and how are you involved?

I’m one of eight artists who’ve been asked by Counter Editions to produce a special print in relation to the Rio Olympics. It’s a great project and I’m really pleased to have been asked to participate. I love the Olympics and sports in general.

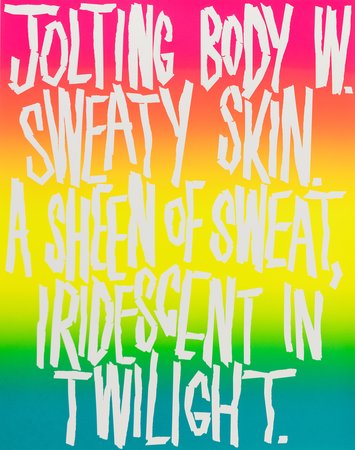

My particular print is an edition of 100 using bright colors screen-printed over masking tape text. When the masking tape is removed, it reveals a poetic description of the experience of watching an Olympic athlete on TV, with their sweaty skin. I very much like the experience of watching it during the twilight hours, when the light bounces off of the athletes bodies in this very shiny, sheeny way, what with their sweat and everything. The text is a description of that.

The colors themselves are also an allusion. I’m very keen on rave posters, which are a big thing here in London. I’ve tried to imbue my print with that aesthetic and these very bright, acidic colors.

Why did you decide to focus on this very sensual, aesthetic aspect of watching the Olympics?

I guess it’s because it’s an aspect of the Olympic Games that’s not often talked about, but one I think is a totally legitimate reason to enjoy them as a viewer. I’d use that description for sports in general, not just the Olympics.

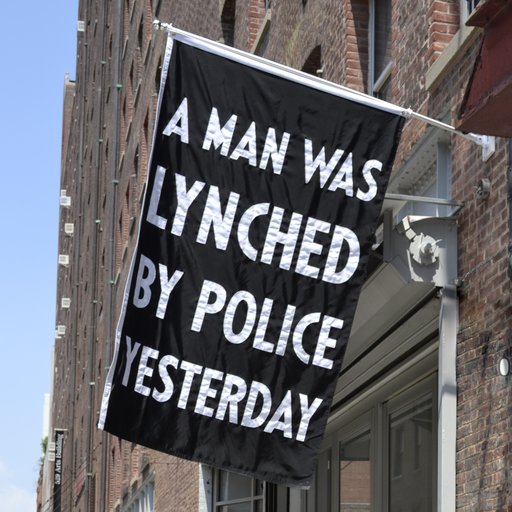

Sweat

(2016) Peake's Counter Editions print, available on Artspace

Sweat

(2016) Peake's Counter Editions print, available on Artspace

You’ve incorporated eroticized sports into your art before, most notably in your 2012 performance piece Touch that saw you staging a five-on-five soccer match between men dressed only in their socks and sneakers. Where does this interest stem from?

For my part, it comes from two things. First of all, I love sport. I play football [soccer] regularly. There’s no irony in my appreciation of sport—I just genuinely love it.

Second, something that I’m fond of doing in my art and exhibitions in general is taking things from one context to make them slightly incongruous in another, mainly the art gallery. I would say that is true of sports to a greater or lesser extent. Seeing a football match in a gallery is weirdly out of context and incongruous anyway. Removing the clothes adds another layer of incongruity that is really compelling and, you know, sexy.

How did you land on performance—particularly the vaguely sexual and often nude kind you favor—as a medium of choice? What does it do for you that other media can’t?

That’s a very interesting question. The first thing is, as a non-intellectual, non-cerebral impulse, performing has always been something I felt compelled to do. From before I even called it art with a capital 'A,' I loved music and playing in bands as well as doing theater and drama at school.

Second, as a viewer I found that whenever I was in the presence of performance it did something to me—ignited me—in ways that I didn’t necessarily experience with other media. It felt dangerous, it felt awkward, it felt gross, it felt exciting, all in ways that were totally transcendent of reason. I found it difficult to put those responses into words. Very often, these responses are negative, but because they are so extreme in me they inevitably lead me to want to try to do that to other people.

In addition to all that, the thing I love about performance is the face-to-face, palpable interchange between the work and the viewer. Performance, I would say, is singularly based on that moment. It’s very much about actually being with the work as you experience it. Above and beyond any other art form, I would argue that if you’re not there to see a performance as its happening, you’re really not having the experience of the work.

You can look at pictures and video of performance, but, really, you’re not getting the experience even slightly. It’s true for performance artists whose work I know well—at least I think I know it well—solely through documentation, people like Chris Burden , Paul McCarthy , Marina Abramovic , Carolee Schneeman . I’ve never actually seen those works—performance is so fundamentally about the actual, live interface between the work and the viewer.

It’s for this reason that I don’t put any of the video documentation of my performances online. I want to be about the viewer being there with the work, smelling the performers' sweaty bodies, feeling the drips of sweat fly off into their face, having that awkward “What do I do with myself?” feeling that can be embodied by being a viewer watching performances.

Duro

(2015), performance at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Image via

White Cube Gallery

.

Duro

(2015), performance at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Image via

White Cube Gallery

.

How do your physical artworks—your iconic scarfed bear silhouette, for instance, or even something like your labyrinthine installation at the Barbican last year—relate to your performances pieces?

First of all, let me preface anything I say by being transparent about the fact that I do not fully know myself. For my part, I think that’s OK. The work that I’m making is an ongoing exploration and investigation. I’m figuring it out as I go, and I frankly wouldn’t want it any other way. If I did have an answer for it all, I’d probably want to stop making that work.

I tend to think that work in different media does definitively different things. That’s an obvious thing to say, but it feels important to bring up because I do work in all these different media. That said, the venue where all the dots get joined up—the sculptures, the performances, the videos, the paintings—is in the context of exhibitions. That’s where I go “Oh, here’s what they’re all doing.” The unifying whole is the exhibition, and that’s led me to think that the exhibition is the singular medium that I work with.

If I were going to start an art school and have painting, sculpture, and video departments, I’d also have the exhibition department, because that’s the place where I think in a cohesive way about what things mean. I do feel like I can break down what any given, individual work might mean to me, but it all ties together in the exhibition.

Where another artist might say, “My whole general idea is this, and that’s embodied in this work in this way,” I don’t really feel like I can do that—I can only do it in the context of a show, where it’s so much about the viewing experience and going on this wandering, narrative-based journey through the show.

Innocently Wears a Bikini

, 2015. Image via White Cube Gallery.

Innocently Wears a Bikini

, 2015. Image via White Cube Gallery.

Jumping off from that, how do you think about these cohesive exhibitions being broken down into their component parts as individual works are bought and sold?

I love it. I don’t feel like it compromises or undermines what I was just saying. I still love individual artworks like paintings and sculptures, I still think that they can have a power, and I still think that I can have a powerful relationship with an object and feel like it can stand up for itself on its own outside of the context of my shows.

I’m often asked, “Eddie, you make all of these different things—how do they all relate to each other?” I don’t really know how they all relate to each other outside of the exhibition, but I can talk until the cows come home about what any individual artwork is doing. Whether it’s one of the bear silhouettes or a mask painting or an individual performance, there’s a set and subset of narratives, ideas, and associations that I might have—associations, by the way, that maybe wouldn’t be clear to any given viewer. There’s often an autobiographical component to a lot of the work that I make, which is visible to a greater or lesser extent.

I’m glad you brought up the autobiographical nature of your work. You’ve collaborated with your siblings on several works and have even incorporated your own teenage diaries into a piece. Why work with such deeply personal, idiosyncratic subject matter?

For my part, if art is not personal and—perhaps to a slightly lesser extent—emotional, then I don’t know if there’s any point in doing it. No point in looking at it, either. I want to have the sense of something being properly at stake.

It’s a bit of a truism and potential cliché, but I think it’s true—many of the best works come about from ideas that at first seem stupid or humiliating or embarrassing. I think that stems from the gross aspect of one’s own experience of being a person in the world. If it’s personal and by extension to that autobiographical, it feels like there’s something urgent at stake. If work is purely analytical, let’s say, then it can seem very empty. It can be very clever, a commentary about non-personal things, but in the end it doesn’t seem that clever to me.

Speaking of autobiography—you grew up in a family of artists. Did you ever consider rebelling by becoming an accountant or something similar?

Oh my god [laughs]. I desperately wanted to be anything but an artist for most of my childhood and adolescence. I was interested in sport and was good at math in school. I wanted to do math or law—I loved the idea of doing something stable and structured, because my vicarious experience of art and artists was one where it was not stable or secure. I saw it as a kind of constant struggle, which it is—I was right in that judgment.

Around the age of 18 I got the bug. I couldn’t help it—I accidentally made some paintings I thought were amazing, and I enjoyed making them. In that moment, I was like, “Oh gosh, you can just do what you love in life and somehow turn that into a career.” That is a distinction to make—I wanted making my art to be my career, whereas the environment I was brought up in was different. There, you made your art, and then you had another career as a separate thing. For me, art, career, and life are all one thing.

You mentioned the idea of incongruence as a fertile site for your work, something I see in your embrace of pop culture, spectacle, and art-as-entertainment. How do you think about the relationship between so-called fine art and popular culture?

I’m not going to be in denial and say that there is no difference—clearly there is. I remember a distinct moment in my art making life where I suddenly realized that the things that I do in my life that are “separate” from my art have as much joy and anxiety and any other very real feelings as my art does, so why shouldn’t they just be one and the same thing?

Throughout my art education I was also going to extracurricular dance classes, listening to DJs and dance music, and playing football. I thought it was silly to put one thing above the other—these things can actually be in the same continuum as my art practice.

You can read Roland Barthes or Judith Butler one day and

The Beano

and

The Dandy

[popular British children’s comic books] the next. All of that, for me, is on the same spectrum of cultural associations and reference points that one has at one’s disposal. I want the work to embody that experience, because it feels real and substantial for me.

"The Forever Loop" at the Barbican, 2015. Image via White Cube Gallery

"The Forever Loop" at the Barbican, 2015. Image via White Cube Gallery

Music is a recurring feature in much of your work. Do you make music yourself?

Recently, I’ve been co-producing music with Anal House Meltdown, the collective name that Prem Sahib, George Henry Longly, and I use for our club night. In all of the great clubs, the DJs that play at the clubs and the promoters that put them on also play their own music. All the Chicago stuff, all the Detroit stuff, all the jungle clubs in the ‘90s that I used to go to, all the people putting on those nights would play their own music, so we wanted to make music that we wanted to hear at our club night. We’ve done one release already and are working on another one. I also want to give a shout-out to my long-term musical collaborator Tim Goalen, who has helped us do that.

I’ve made a lot of sound works that aren’t musical as such but involve the same sort of applications. Also, importantly, all of the performances that I make feature original compositions that are made collaboratively by the cast of my performances and me during the rehearsal period. Music and sound are really integral parts of everything that I do in my work, so, broadly speaking, “yes” is the answer to your question, but it’s a bit more intricate than that [laughs].

You recently relocated to London after an extended period living in Rome. What drew you to the Italian city?

I jump between London and Rome quite a lot, because I work with a gallery in each city. Even if I didn’t work with the gallery in Rome, I’d still go there a lot because I really love it there for a whole number of reasons.

I really like the fact that it’s so remote from contemporary life and therefore contemporary art, in a global sense. It’s something that totally frustrated me and made me say “I can’t live here” when I first moved to Rome, but it ultimately came to be the thing I appreciated about the city. I love stepping out of places like London, New York, or L.A., where everything is moving at five million miles an hour and you’re on the beating pulse of contemporary life. That’s great for a whole set of reasons, but sometimes being in a place like Rome—where there’s an almost transcendent experience that has nothing to do with contemporary life—can be quite rejuvenating and alien in a way that is, inversely, quite contemporary.