For a long time, the painter Dana Schutz has been saddling her figures with absurd and patently impossible tasks: eating their own faces, for instance, or building a boat while simultaneously trying to sail it. In her latest show at Petzel in Chelsea, "Fight in an Elevator," Schutz’s characters finally seem to have had enough. Frustrated with the conditions of their subject-hood, they strain against their frames, press out on the picture plane, or violently push and shove each other.

Their gestures, however, are not really uprisings against the artist. Rather, they're demonstrations of Schutz's philosophy of painting, which for her is always a medium of frantic action in a restricted space. They also capture a kind of zeitgeist of tension and compression; the show's title and two of its paintings, for instance, refer to recent viral episodes of celebrities misbehaving in elevators (the scuffle between Solange and Jay Z, to name one example).

As she prepared for her first Canadian solo (opening October 17 at the Museé d’art contemporain in Montreal), Schutz spoke candidly with Karen Rosenberg about the personal and public inspirations for her latest works, the way drawing is creeping into her painting process, and how having a child changed the way she looks at art.

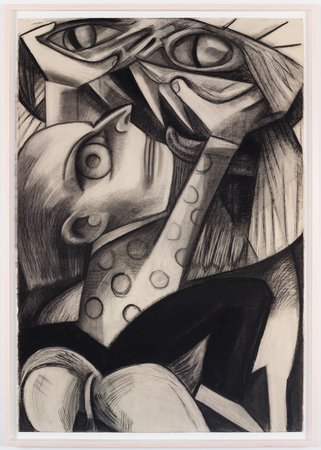

Lion and Tamer, 2015 (All images courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.)

Lion and Tamer, 2015 (All images courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York.)

We last spoke five years ago, and a lot has happened in your life since then—you’ve had a survey that toured the country ("Dana Schutz: If the Face Had Wheels," organized in 2013 by the Neuberger Museum at Purchase College) and you’ve switched galleries, from Zach Feuer to Petzel. What else is new with you?

Well, my husband and I had a baby this year. He’s 14 months now. So everything is different. I have also been drawing a lot more in the past three years. It’s a quicker way to work out ideas, but it’s also changed the structure of the paintings a lot, because you’re always working on the same size paper and it can be kind of awkward to force an idea into this standard format. It changed how I was thinking about the space in the paintings—they started to have a lot more compression.

I began to do more preparatory work when I was starting the paintings, leaving the canvas open and wet and drawing out and wiping away a lot more—drawing into the paintings. Making preliminary drawings on the canvas, really focusing on the composition, is something I hadn’t done so much before. I think it creates a different kind of space—flatter and more vertically structured, even in the horizontal paintings. I was thinking about Beckmann a lot, about how he would get a lot of narrative information into his awkward, unusual spaces.

Fight in an Elevator 2, 2015

Fight in an Elevator 2, 2015

In this show at Petzel, compression isn’t just a spatial attribute of the paintings—it’s often the subject. You’ve placed your characters in confined spaces and claustrophobic scenarios, as in the two paintings titled Fight in the Elevator and another one set in the shower.

I think the tension of the stretcher and the framing edge, the internal compression that goes on within a painting, has a lot to do with these kinds of physical things within the painting. I think you can get different tensions, depending on how you place the subject within the space of the painting.

I was also thinking about interiority. In the past 10 years there has been a lot of talk about painting as something that exists as an object—something that can be moved around or propped up somewhere—and not really a lot of talk about the interior space of the painting. I think they both have a kind of truth to them—a painting can be an object in the room, but there’s also this picturehood that can happen inside the painting.

The subject can also have a physical sensation inside the painting. Some of my subjects are involved in physical acts inside the painting, bumping up against the edges. It was happening naturally, the way I was working—the subjects were getting so structured into the paintings that they started to become aware of their environments and began to step outside.

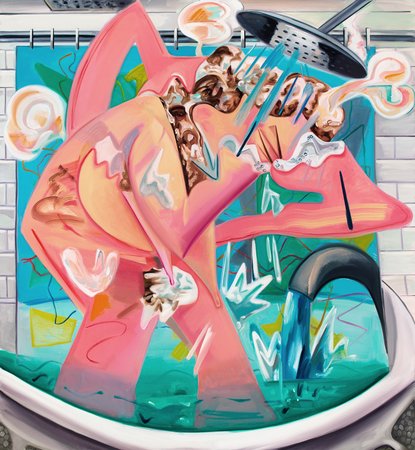

Slow Motion Shower, 2015

Slow Motion Shower, 2015

You’re saying that your subjects started to push back against the structure of the painting?

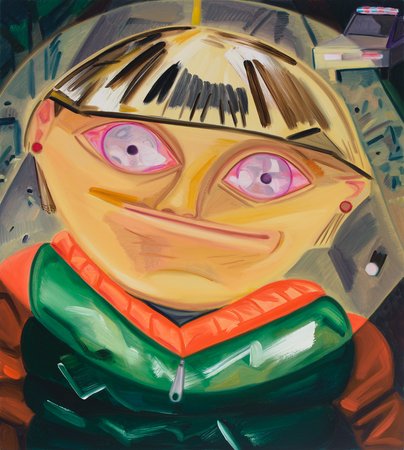

Maybe. I think that’s something that images do anyway. There’s a small painting in the show [As Normal as Possible] of a woman who’s being pulled over by the cops—I really wanted that expression on her face of revealing and concealing at the same time, like when you’re being questioned by the police but you’re trying to look normal. I wanted that doubleness to the expression. And I was thinking of the viewer as being in the role of the police.

It was inspired by something that my husband and I saw when we were walking in St. Louis—we saw a woman being pulled over. We had so much emphathy for her—I remember being pulled over one time when I was a teenager, and not being on any drugs but feeling like I was. You just have this feeling like you’re immediately guilty.

As Normal as Possible, 2015

As Normal as Possible, 2015

That’s interesting, especially because policing in the St. Louis area is a really heated issue right now. Is that something you were thinking about, as you made this painting? Your works do sometimes have these oblique political references.

No, it wasn’t, but it’s something I’m thinking about now. And there were a few images in the current show at Petzel that were in the media, of people fighting in elevators. I think any kind of fight brings up the politics of what’s going on in that fight. Who’s the aggressor? What’s going on? I think there are certain subjects that feel like they could work for painting but also have broader resonance.

To be more specific, those Fight in the Elevator paintings reference episodes that became a viral media sensations. Was that something you were thinking about?

It’s interesting how that kind of image taken from an event in an elevator can become a huge media event, but it’s also so ephemeral. An elevator is always changing over. Even the form of an elevator feels like an eye opening and shutting, or the shutter on a camera. I felt like it has this relationship to how information changes over anyway, in culture right now. Images come and go.

Elevators are also these strange public/private spaces, where people forget they’re under surveillance.

There’s something like it in dressing rooms, where you feel like you’re coming in alone but you’re never really alone. There’s a blindness to that kind of space—you don’t really look at anything. You just wait until you get to your floor.

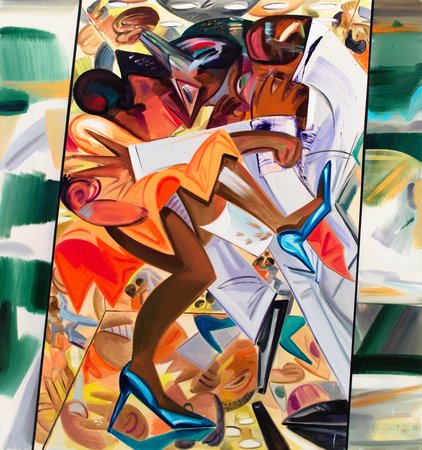

Fight in an Elevator, 2015

Fight in an Elevator, 2015

These paintings have something of a Cubo-Futurist look to them, in the angularity of the figures and the way they’re broken up into multiple views, and people have been talking about them in those terms. Do you see them that way?

I actually don’t like a lot of Cubism, except for this amazing Picasso painting at the Met, of a woman in a chair. I never really liked Cubist paintings—I just thought they were blended together and they were sort of brown. But I was interested in compositions that would really affect how I was making the subjects—like, I’ll put the jaw here because I need this angle here to build this picture. It changed how I was approaching the figure.

There’s something about Cubism that schematizes things—everything is broken down to fit the structure of the painting. But I don’t want to make paintings that just turn into design—it’s something I’m really aware of.

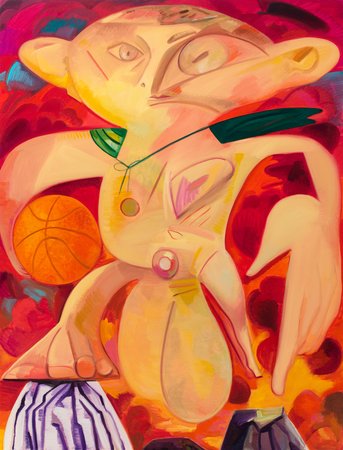

Lion Eating Its Tamer, 2015

Lion Eating Its Tamer, 2015

Whether Cubist or not, the figures in your paintings are becoming more abstract—as in Lion Eating Its Tamer, where the figure is so flat it looks like a paper doll and the lion’s mouth is a perfect hemisphere.

One thing I’m interested in is the idea that the subject can be material. That was different for me in this show—it was there in a lot of the subjects, but it could be at odds with the structure. With the shower painting, the subject became this wavering, slow line. I could think of the subject as material and how it worked in the space of the painting, too.

In places your figures seemed to be not only fractured but also distorted, as if they were being pushed and pulled by funhouse mirrors or photographed by André Kertész.

In Big Parts, Small Parts, the figure gets flattened and then torques to the side, almost the way an image would if you look at the painting from the side. And in Fight in an Elevator there’s a face that’s sort of being squished, in the way that Holbein painted that skull—it’s strangely at an angle and also flattened. Like you’re looking through a glass and maybe the glass is turned, slightly.

Big Parts, Small Parts, 2015

Big Parts, Small Parts, 2015

There’s also a sense, in that painting and others, that you’re seeing the figure from different distances at once (as well as different angles).

That was something I was thinking about with that painting, and also in the making of other paintings—a lot of them read graphically from a distance, but you could also have a more psychological experience up close. I think that might come from having a kid—you’re spending so much time looking at this little body.

A lot of the other subjects felt personal too. Shaking Out the Bed shows a couple in bed, but it’s sort of aerial. I wanted to paint a subject that shouldn’t really be painted on that scale, an intimate subject on a very big canvas.

How else did the experience of having a child impact this body of work? I should say here that this is a question that too often is posed only to female artists, never to men who have just expanded their families. But it seems important to mention it now, because it came up earlier and because one of the paintings shows a woman breastfeeding.

I know! Yes, there’s one that’s sort of about breastfeeding, with the woman sitting in the chair. It was something I never thought I would want to paint, but it’s the first thing I made when I came back to the studio. It had been so much of my experience for the past month, and I found it a really difficult experience—a physical challenge.

More than anything, having a kid changes how I look at paintings with kids in them. I didn’t expect that. When you talk about paintings of kids, people say, “Oh, like Mary Cassatt.” But I don’t think it’s gendered—men and women alike have painted their kids, because of the weirdness and amazingness of having one.

Can you name some examples from art history that inspire you, or that you’re now looking at differently?

I love Otto Dix’s paintings of his kids—they look so demented and hard and hollow, like you could knock on their heads. He painted his daughter with this cartoonishly large bow in her hair and huge eyes. But they’re so accurate too—there’s one of him holding a baby, and it’s a newborn and it’s so wrinkly and vulnerable. You really get that from the painting.

And in all of those old ugly babies from art history—the mother-child scenes in religious paintings—all of those people really focused in on that because they really loved their kids. Baby Jesus was just a way for them to paint their kids!

Glider, 2015

Glider, 2015

What exactly is going on in Glider, the “breastfeeding” painting? The figure looks sort of like a de Kooning “Woman,” but there’s a baby who seems to be tumbling out of her lap.

I wanted that whole painting to feel like a clock—all the information is sort of spinning, in the painting, or the painting itself had a clockwise motion. That’s how I was seeing it in the studio—“I think it’s spinning that way.” There’s a baby on the lap, but the head has sort of rolled off the lap. I wanted the lap to feel like an unstable situation, and the features to be sliding off the woman’s face.

When you’re in the chair, time goes by—day and night, day and night. You’re always afraid of falling asleep in the chair—there’s this feeling of drifting. It was a very particular time, that I’m glad is not happening right now. There’s a legless feeling to it—you can’t really get up and move around. That’s how I felt. That’s what I was thinking about with the painting.

It ended up looking pretty abstract. I think it would be good to re-approach the subject, with more clarity about what the subject is. Being in that moment, that’s how I could paint it at that moment. But it would be interesting to approach again now that I’m not in that moment.

What’s the most recent work in the show? Which one comes closest to the moment you’re in now?

The most recent painting is Shaking Out the Bed. I felt a lot of energy going toward that painting. I knew that the way I wanted it to look—it be had to be wet-on-wet—so I had to paint the bed very rapidly and have the surface be really open. It was a lot of long nights, but it was really fun to paint. You had to be constantly moving, the whole time.

Shaking Out the Bed, 2015

Shaking Out the Bed, 2015

Is that painting a jumping-off point for your next body of work? Where are you going from here?

I liked painting those altercations—I think I would like to make some more fights! And I’d like to try to make another large bed painting, maybe with a single figure.

Right now I’m painting a boy popping a bubble in the Alps. The whole landscape is reflected in this bubble. I always like those science paintings where they show you how to do something in the painting. Like Chardin’s bird in a glass jar, which was supposed to be about oxygen.

What are some of the other artists or works you’ve been looking at?

I’ve been looking at Charles Burchfield a bit. And with those elevator fights I was thinking about a painting I saw in the Cleveland Museum of Art, a great little Bellows boxing scene. I used to love that painting. It’s kind of populist, but I was interested in making a painting like that, especially in the first Fight in the Elevator painting. I like the action, and the positioning of the bodies is difficult to figure out.

Which emerging artists interest you right now?

I love Ella Krugulanskaya’s painting. I think she’s great. And Gina Beavers—she makes super-weird, knarly paintings.

I’d love to know how you come up with some of the ideas for your paintings—you’re such a creative thinker. Do you have any routines or rituals, like meditation?

I like making a music mix to paint to—usually an energetic mix. Sometimes I’ll write, and try to figure out different ideas and see if anything could work. And this is really embarrassing, but sometimes I stretch. I’m a brittle person, so I do that when I’m going to start a painting. You remind yourself of your wingspan, of what you’re able to do.