The photographer Andrew Moore has long been a sensitive explorer of cities in flux, one who is drawn to urban blight and neglect (as in his well-known series on Detroit) as well as sudden construction booms (like the one in Abu Dhabi). Moore's photographs, which have been seen at Yancey Richardson gallery in New York and published in the pages of the New York Times Magazine, caution us that today's grand architectural masterpiece is tomorrow's monument or ruin.

In his new book Dirt Meridian (due out on September 29 from Damiani), he shows us a rural landscape undergoing a similarly fraught transition. Set largely in the Great Plains, the publication takes its title from the 100th meridian—the line that runs from North Dakota to Texas and more or less slices the country in half. As seen in Moore’s photographs, many of which were taken from a low-flying Cessna piloted by a local crop-duster, a large number of the region's farms and cattle ranches have been converted into fracking sites or conduits for oil pipelines. In places, though, the camera hovers over a herd of antelope or the remains of a homesteader's cottage, reminding us of the land's long-term inhabitants and its earlier generations of fortune-seekers.

In a conversation with Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg, Moore discussed the challenges of picturing cattle country without succumbing to cowboy clichés, the possibilities of aerial photography, and the changes he witnessed over a decade of working in this sparsely populated but resource-rich region.

What led you to this remote and, in many places, desolate landscape?

I met Carol Hepper, a sculptor from North Dakota who works with a lot of materials from that area and who invited me to come out to her brother’s ranch in Keene, North Dakota, to attend a branding. I made this picture of a roundup where cowboys and cowgirls and some dogs and kids took this huge herd of cow calves and formed them into an enormous circle before leading them into the pen to be branded. I was really taken by this symbiosis of man and nature—this pristine, idyllic landscape and this geometric formation, and the combination of formalism and narrative. So I started to go back out there.

The first couple of years were frustrating, because I didn’t really want to make a story about cowboys— I didn’t want to get involved in too many of the clichés of Western art. The breakthrough, for me, was the picture Homesteader’s Tree, of that lone tree out in the middle of nowhere. I realized, I don’t have to talk about this cowboy lifestyle; I can tell the story of the place through the land itself, through the dirt and emptiness of the place. It took a long time, and a lot of bad pictures, to come to that realization.

How did you get from that initial attraction to the landscape of the Plains to the organizing concept of the 100th meridian?

I started to read about the area, and I came across John Wesley Powell’s report on the Arid Lands [Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States], which were the lands west of the 100th meridian, and it started to click: this is where the country really shifts, where rain falls off and it starts to become a very different kind of land. Powell realized that early on, that the laws and regulations would have to be different because of the lack of water out there.

And then there’s Wallace Stegner’s account of Powell [Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West]. And of course, you’re familiar with Blood Meridian [the Western novel by Cormac McCarthy]. So I had all these things kicking around in my head, about the 100th meridian and Blood Meridian. I was visiting with a friend one night who’s a songwriter, and this term “dirt meridian” just popped up. I thought, that’s it—that’s exactly what it is. It’s this empty, dirty middle line. And it also refers back to the Great Depression, which was also known as the “dirty thirties.”

Round Up No. 2, McKenzie County, North Dakota, 2005

Round Up No. 2, McKenzie County, North Dakota, 2005

Were you also thinking about the history of photography in the area? Surveys of the area West of the 100th meridian, by photographers including Timothy O’Sullivan and William Bell, are well known. What about photography in the area of the meridian itself, the former Nebraska Territory?

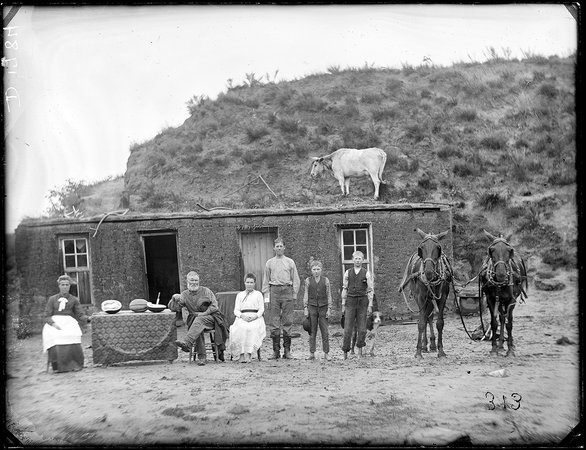

In the later part of the 19th century, there were a lot of itinerant photographers who came through these newly homesteaded lands and would, for a small amount of money, photograph the homesteaders in their soddy [sod house] or shack. Some of those pictures are so remarkable, so expressive—just a big white sky and a family. Often the kids are barefoot, and they’re standing outside the most primitive home, and they’ve taken all the possessions from the outside because the inside is so dark, so you see the table and the chairs and a few objects and the family.

Probably the most famous of those photographers is Solomon Butcher, who photographed in Nebraska. I looked at a lot of Solomon Butcher photographs, and my favorite one is actually one reproduced in the book. There’s a cow on a hill in the background, and it looks like it’s actually standing on the roof of the house.

A photograph of the Rawdings family in front of their sod house, by the itinerant photographer Solomon Butcher.

A photograph of the Rawdings family in front of their sod house, by the itinerant photographer Solomon Butcher.

There aren’t a lot of pictures of the Plains that express the nothingness, the emptiness, the void of the land. It’s a challenge, in terms of picture-making, to depict that.

It seems like those depictions exist mainly in literature. Your book has a short but evocative preface by Kent Haruf, the author of Plainsong, who writes of the landscape: “It may not be pretty, but it’s beautiful if you know how to look at it. You have to quit thinking of trees. You have to quit thinking of green.”

It was so great to get him to write that preface. I knew he wasn’t well—he just died this past fall—and I think the preface is actually one of the last things he wrote.

Obviously there’s also Willa Cather, and Mari Sandoz, who wrote Old Jules. Also there’s a wonderful book I read recently called Stoner, by John Williams. The author talks about a professor who’s the child of dirt farmers in Missouri, and he goes to their funeral and is talking about how they worked this dirt their whole life—how they got nothing from it and were just returned to it. It’s a very powerful passage. And then there’s the literature that came out of the Great Depression as well—that’s in the backstory. But the epicenter of the Dust Bowl was really in the Southern High Plains, and the work that I did was more in the northern part of that High Plains area.

Did you have a base that you kept coming back to, or an area of focus?

The panhandle of Nebraska—the tiny little point that sticks out and touches on Wyoming and Colorado. It’s also the location of the Sand Hills, which is this wonderful part of America that was marked on early maps as the Great American Desert. In fact, it was sandy—there were sand dunes. It slowly grassed over, and now it’s great cattle country. It’s this unique part of the country, and many of the pictures in the book are actually from that area.

Currently, that area is central to the controversial Keystone XL Pipeline plan.

Exactly. They wanted to put the Keystone Pipeline right across the Sand Hills. It’s interesting because right underneath the Sand Hills is the Ogallala Aquifer. The water comes through that sand and goes right into the Aquifer. The area looks like nothing, at first, but it’s incredibly important as a resource.

You also reveal other aspects of the oil boom, especially in your pictures from the Dakotas. One of them shows a “man camp,” a cluster of trailers housing the largely male workers at a fracking site. Another depicts a gas flare, used to burn off the gas from oil wells that can’t be stored or shipped because the infrastructure in that region hasn’t caught up to the pace of production.

It’s not a book about fracking specifically, but I wanted to show that the landscape is not stuck in time—it really is evolving. I wanted to say, we think there’s nothing there but actually there’s a lot going on in this area.

I’m not trying to stand at a distance and say, "We’re ruining the landscape"—I’m trying to look at how the land has shaped us, more than how we’re shaping the land.

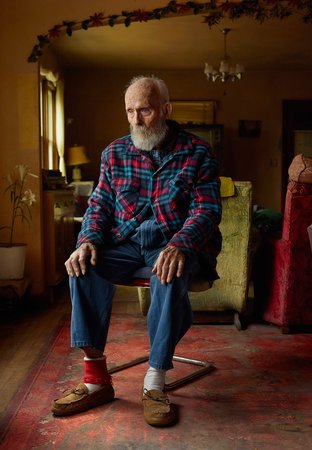

Uncle Teed, Sioux County, Nebraska, 2013

Uncle Teed, Sioux County, Nebraska, 2013

During the 10-year period when you were working on Dirt Meridian, you were also working on your book Detroit Disassembled.

Yeah, I did the whole Detroit project right in the middle of this, and I went back to Cuba once or twice during that time period. But it was always in the back of my head that I wanted to do this, to find my own way of telling that story of the West.

Speaking of Detroit, the idea of post-industrial decay in American cities has been integral to your work. How are you translating that to the landscape?

Detroit was so massive and emotional, for an American—just seeing what this place had become. I wasn’t just going to go to Toledo or Cleveland and do the next project. But the theme that came up in Detroit was nature coming back into the emptiness left by man, this relationship between ruins and nature. There are many references to that in the new book.

There are abandoned cities in Iraq and Afghanistan, and we have the same thing here. I tried to show these strange American ruins, out in the middle of nowhere—to show what our own indigenous ruins really look like, how they’re created from the earth. The last picture in the book, of the Murray House—that’s a concrete block house that was formed from the sand beneath it. Those blocks are actually composed of the soil right underneath the house.

The Murray House, Sears Roebuck Rockfaced Wizard No. 52, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

The Murray House, Sears Roebuck Rockfaced Wizard No. 52, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

You also have some shots of decrepit interiors in the book, photographs that echo some of the pictures from Detroit and other series. Critics have called these kinds of images “ruin porn.”

There are a couple of images like that, but I don’t know if it’s “ruin porn.” The one of the sod house, for instance—I really wanted to get that sod house, because it came from the dirt and it returned to the dirt. I’m interested in the buildings as they begin to lose their structure and become more sculptural—how there’s a kind of surrealness that the shapes take on.

It’s about ruin, but it’s also a way to talk about ambition and failure—not just, "Look at this shack falling apart." I’m always after a larger narrative when I use architecture in that way. The grand ambition people had, to construct this prairie castle out in the middle of nowhere that looked like a Renaissance palazzo!

Thorne House, Stanley County, South Dakota, 2014

Thorne House, Stanley County, South Dakota, 2014

In your earlier shots of crumbling and abandoned cities, there’s often a sense of trespassing or forbidden access. Is there an equivalent in the landscape of Dirt Meridian?

What was remarkable about flying, out there, was that there were no flight paths; there were no controlled zones. There was so much freedom, to go wherever you want, to follow the whims of the landscape. We could fly 10 feet off the ground for 50 miles. We could not have done that here, even in the middle of New York State. There are some interesting comparisons with Detroit, but rather than having to trespass everywhere it was wide open.

Also, in many cases you could not find those places unless somebody took you. They’re not on a map; you’d have to have a rancher or some local person show you where they were.

So you had to really tap into those local networks. What was that process like?

Living out in those remote zones you have be a very substantial person, or you die. You have to fix stuff and deal with your neighbors. I was welcomed by most people—I stayed at their homes, and they showed me everything.

These sixth, seventh generation descendants of Homesteaders have a continuity to their history. They’re so connected to the land, and have all these stories to tell. It’s not a place that people are moving in and out of all the time. They know a lot about the Native American tribes, artwork, and habits, and the story of the land.

Pedro, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

Pedro, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

Some of your photographs of herds of animals have a strong resemblance to Native American art from the Plains. Your picture of grazing buffalo shown in silhouette at dusk, for instance, reminded me of paintings on animal hide I’d seen in last spring’s Metropolitan Museum of Art show “The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky.”

Those big buffalo hide paintings make sense to me—you need an epic canvas to show the land and the scale. There are lots of references throughout the book to the Native Americans. I didn’t want to address the reservation system itself, but there are photographs of the land in the Pine Ridge reservation.

It was definitely conscious on my part to include as many animals as possible, to show that they are integral to the landscape and to the lifestyle out there. I think that’s what the Native Americans also felt—that this was a land for the animals.

Usually with the plane you would get one or two passes, and then the animals would start to get a little restless. We tried not to spook them. The buffalo, you get one pass with them—on the second pass they start running. And once you get buffalo running, they’ll just run all day, so I liked to photograph them from the ground.

Most of the landscapes in the book were shot from the air, with a kind of hovering perspective. Why did you decide to do that?

I’m not an aerial photographer, but I met the pilot Doug Dean, who is a crop-duster, and things gained a lot of momentum. Crop-dusters are such amazing pilots—they fly every day, 12 hours a day, all summer long, and they fly very low, just a few feet off the ground. This kind of low-altitude photography really suited what I was trying to do, because I wasn’t trying to abstract the landscape; I was trying to draw narratives from it.

I knew Emmett Gowin’s work very well, and I felt like he had done that style of aerial photography so well—abstracting the land and using the patterning of the land—that there was no way I was going to try that. Flying so low, with Doug, we could look at real things but have them in this kind of deep space.

The Yellow Porch, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

The Yellow Porch, Sheridan County, Nebraska, 2013

Working from the air also allowed you to cover more ground.

That plane went almost 200 miles an hour—we covered hundreds and hundreds of miles in a day. It’s the kind of landscape that begged for that approach. Many of the ranchers have planes—it’s a pretty standard way to get around out there. It wasn’t uncommon for us to fly somewhere, take some pictures, land, drive five minutes to the rancher’s house, have lunch, take some photographs on the ground, and then just drive back to the plane and get up.

We’re living in a renaissance of aerial photography, in which amateurs and professionals alike are using drones. Was that something you thought about?

I think it’s one of those serendipitous things, where I started doing this work and then the drones came along—I just tapped into the zeitgeist of these perspectives. For me, drones would have been very difficult to use because I had to cover so much ground—hundreds of miles. And I had a pretty expensive camera that I didn’t want to crash on the drone.

What changes did you notice in the region, over the course of a decade of working on Dirt Meridian?

I was thinking about that first picture in the book, the roundup in North Dakota. I went back to visit that same place last summer, about nine years later, and it was completely covered with fracking locations.

That pristine, idyllic landscape that I thought would never change has become the epicenter of fracking in North Dakota, McKenzie County. There were new county roads, trucks with water and gas, pipelines. I just couldn’t believe what had happened. Things that you think won’t ever change will change in less than a decade, very dramatically.