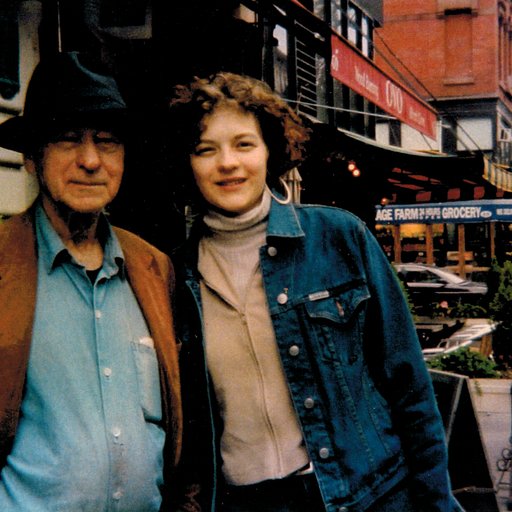

“Children” and “pornography” are not words we generally like to hear in the same sentence, and yet it strangely works if you happen to be talking about the artist Aura Rosenberg. These two topics have proven to be fertile grounds for Rosenberg’s experimentation; the latter enters her work as appropriated erotic images pasted onto rocks or copied as paintings, while her persistent meditation on childhood is explored through various photo series featuring Carmen, her daughter with the artist John Miller, and their adoptive city of Berlin.

Ranging across media and displaying an affinity for both critical theory—the celebrated German philosopher Walter Benjamin is a frequent reference point—and her storied contemporaries, Rosenberg’s work handles her sometimes weighty subjects with a light touch, creating photographs and objects that allow us to think through such issues with humor and a degree of clarity. Artspace’s Dylan Kerr sat down with the artist to learn more about her circuitous routes to inspiration, including everything from practical jokes and teary seven-year-olds to obscure memoirs and the props in '70s porn flicks.

How did you first find yourself making art? Was there an original impetus towards pursuing the path of an artist?

If we go way back to being a child, I think my first idea was that I would illustrate children’s books. I went to Sarah Lawrence for college, which was all women at the time, and when I got there I was doing these figurative stain paintings. I wound up going to the Whitney Independent Study Program because my teachers were Marcia Tucker and Barbara Rose—the two of them urged me to go to the Whitney Program, which was still in its early stages. That just completely turned me around about what it was to make art. It became a very strange thing, and very difficult in a way. Going to my studio was scary for a while.

What shifted there?

I was doing these figurative stained paintings as a high school student and in early college, and I was used to my teachers really liking what I was doing. When I went to the Whitney Program, we had a crit one day with Richard Artschwager. He didn’t know whose studio he was in, but he said to Ron Clark, “Why is this person doing this?” Some of my teachers might have questioned things like, “Why is this so red?” or say that the composition was a little off, but nobody ever asked the simple question of why I was making something. I really had to stop and ask myself, “What am I doing? What am I making?” The question of “What is a painting?” became so strange, and I would just stare at my canvas and wonder, “What is this supposed to be?”

I just thought I would stop making art. It was the first and one of the only times I’ve ever thought that I just can’t do this, but I was still in the program and had to stay there. After a couple of weeks I started drawing again, and gradually worked my way into making some really different work and learning much more about the discourse around painting. There have been a few more times when it’s been very hard to go on, but I always have. I think finally at this point in my life I’ve realized that this is just what I do.

I’ve read that your Dialectical Porn Rocks series started as a practical joke on one of your friends before evolving into something more. I’m wondering if you can tell me a little more about how they came to be.

Before I started on those, I was making body imprint paintings in my Canal Street studio, which inevitably had a kind of sexual connotation. I think those were some of the earliest paintings of mine that dealt with what you might call sexual themes. I wasn’t thinking so much about erotic imagery, but more about making a mark or figuration of a body without depicting it, without having to will it into being. It’s already there—you paint your body, you print it, and you have a figure.

Around this time, my husband John and I rented a house in the country with a bunch of artists—Mike Smith, Perry Hoberman, Mike Ballou, and several more. It was so much fun. There were these huge prefabricated houses, and there was a trout stream nearby. I had room for a studio, but I just felt like I didn’t want to transfer what I was doing on Canal Street to the country. It somehow seemed wrong. I had been thinking about how I wanted to get away from the sort of fetishism that art, I guess, ultimately is. I was trying to think of a way from this quality, but I didn’t know what to do.

Mike Ballou was making these sculptures out of porn images, and he’s also a trout fisherman. I thought, “I’ll make a real fetish! Instead of trying to run away from it, I’ll totally embrace it.” I stole some of his magazines, pasted the pictures on these rocks, covered them in resin, and put them in this trout stream. I did that, but then I looked at them and thought that there was really some food for thought there. I tried photographing them then, which were the first photographs I ever shot. I was really amazed at the way these rocks looked through the lens of a camera. It wasn’t until a while later that I started thinking about them as things in themselves, as something that I could install indoors or outdoors as a sculpture.

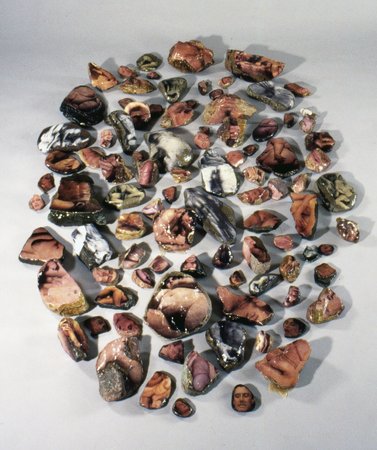

Dialectical Circle of Rocks, 1989

Dialectical Circle of Rocks, 1989

How did this shift between thinking about them as photographs of something to thinking about them as things in themselves occur?

I had a presumption that they could only be photographs. Then Jose Freire had this gallery called Fiction/Nonfiction and he wanted to show some of the work, and I thought about just making a big circle out of the rocks. That was the first time I’d ever shown them that way, and I found it really interesting. I decided that they could be that also, that they could be both. Think about figurative stonework, starting from as far back as you can imagine—the Venus of Willendorf, classical Greek statues. The desire to make flesh out of stone is an old story. But I wasn’t really thinking about that. I don’t know if this is a great comparison, but when I did that circle they felt a little bit like Richard Long with porn.

I definitely see an element of his work at play here. Speaking of land artists: these aren’t just porn rocks, but dialectical porn rocks, a term you borrow from Robert Smithson’s 1973 essay “Frederick Law Olmstead and the Dialectical Landscape.” In what way are your works dialectical?

I think it has something to do with the indoor and the outdoor. These rocks that I found in nature were then recontextualized in a gallery space. This idea of bringing nature indoors functioned sort of like Smithson’s installations functioned—that there is this conversation between indoor and outdoor, between nature and a presumed naturalness of sex that, in the magazines I was drawing these images from, was actually very mediated. The body itself was divided up into parts, and that supposed naturalness was very circumscribed.

Dialectical Porn Rock: Flower Woman, 1989

Dialectical Porn Rock: Flower Woman, 1989

You’ve returned to working with pornographic images with your series “The Golden Age,” after a long hiatus following the birth of your daughter Carmen. These new paintings are based around some of the same photos from the porn rocks, this time painted over to create an appropriative new work. Why did you stop working with these images more than two decades ago, and what’s brought you back to them now?

I think my work follows the trajectory of my life. It’s true, I had a daughter, and that was very absorbing, but that wasn’t really why I stopped using the porn images. It wasn’t a programmatic decision to start making work about childhood either, but I was very involved in a lot of things that had to do with her and childhood, which drew me away from the work I was doing with painting and pornography. Carmen actually encouraged me to go back to that work—she said it seemed like they weren’t finished.

A few years ago, James Siena asked me to do a show at his little space called Sometimes (Works of Art). He asked me if I had any of the little porn paintings that I’d made all those years ago. I didn’t have any, or I didn’t know where they were, but there was one that I’d had laying in my shelf for a long time unfinished. I’d just stopped it in the middle. I decided to just finish that painting. It’s interesting, taking a painting from 1989 and finishing it in 2010. I was interested in doing it again, and that opened up all this new work with paintings.

Coming back to pornography years later, I was like Rip Van Winkle. When I woke up again and looked for the material that I’d been using in ’89, it didn’t exist anymore, or at least wasn’t being published. You’d have to go to vintage stores to get it. I remembered some of the actors who’d been in those big ensembles of actors who performed in these productions, especially this one couple: Kascha and Francois Papillon. She’s an Asian woman with blonde hair and a butterfly tattoo on her butt, and he’s this really beefy French guy. They supposedly only worked with each other, and they wouldn’t have sex with other porn actors.

I googled them, and what came up was “the Golden Age of Porn.” I thought this was amazing, that there was this period that I had been a part of that is now called the Golden Age. When I then googled the golden age of porn, a lot of stuff started coming up, and that’s what I’m working with now.

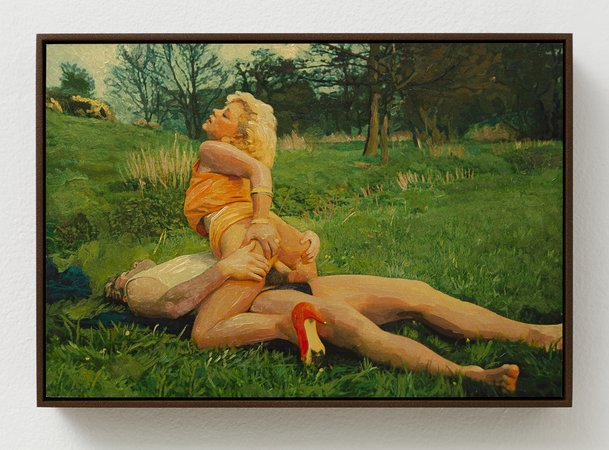

Landscape with Red Shoe, 2013

Landscape with Red Shoe, 2013

Given the explosion of Internet pornography in the years since 1989, do you still think these kinds of porn images have some sort of transgressive power to them?

I’m not sure. I find the images that I’m working with almost quaint, in a way. I’m always surprised when people are shocked by them.

Are people still shocked by them?

They are, and I don’t feel that way. I feel like they’re almost relics. It’s interesting that sexuality can go through these fashions or styles like anything else. It’s like in parenting—there’s a certain kind of stylization around how you bring your child up that really changes. It’s really cultural.

The Golden Age period lasted from the ‘70s to the late ‘80s, and it really ends with AIDS. It’s a little far to say it was a utopic period, but it was a time when women from the suburbs were flocking to the movie theaters to see Deep Throat. There was this real openness, with all kinds of liberation movements. Maybe it was a kind of golden age. I think all of that feels very different now. That’s why I say it feels like a relic, like a fiction from the past.

These works don’t read as criticisms of the porn industry, but neither do they come off as celebrations. What’s the function of the pornographic images you appropriate for your work?

It’s a hard question. I feel that a lot of what I’ve been talking about are formal qualities, but you’re right—you could use a picture from the front page of the New York Times. Part of the pornographic image is that it does have the power, potentially, to really physically affect you. You have to enter into the fantasy of what’s being depicted. It’s a little bit like theater in that way—you have to suspend disbelief.

Years ago, making this kind of work felt like being a bad girl, in a way. It was transgressive. I was pretty good friends with a lot of guys who I felt were doing this in their work, like John with his brown work or Mike Kelley—I wanted to do something that felt like maybe it could have this kind of disruptive effect. I think that was my initial impulse, just to do something that felt transgressive. Now, I can’t see them that way at all.

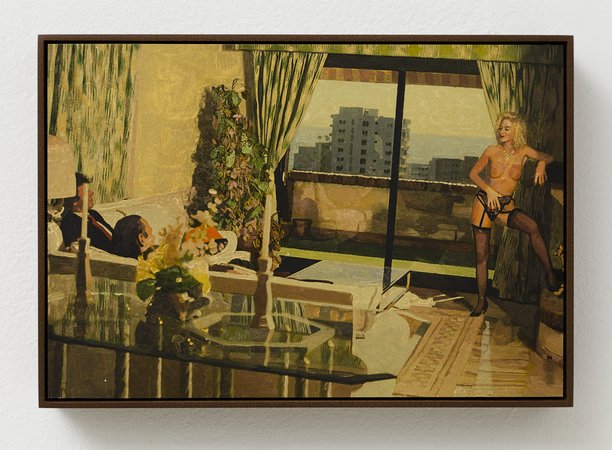

There’s a whole set of issues around that work that I don’t think have very much to do with pornography today. I don’t really know anything about what’s going on in porn now. My students [at the School of Visual Arts and Pratt] will tell me that most of them have watched or made some kind of amateur porn, and that these productions don’t really exist anymore. My biggest questions were about why these productions looked the way they looked, because it wasn’t just about raw sex. It was always in a specific setting, usually a very cultured one in the country or a beautiful house with books and wine and art objects around. The productions tried to be art, maybe as a way around some of the censorship laws of the time. The props are so interesting in relation to what’s going on, which I don’t think you have today at all.

The word “obscene” comes from ancient Greek theater, where it refers to something outside of the scene. There was a screen behind the actors, not in front of them, and everything that it was felt you shouldn’t see, like extreme emotions or murder, happened behind this screen. I got interested in this idea, that something that's outside of the bodies and the image would actually be the obscene. There’s so often curtains in these pornographic scenes—that’s an ongoing interest of mine now, the scene and obscene in the Golden Age.

Men With Golden Green Curtains, 2013

Men With Golden Green Curtains, 2013

Your work in “Berlin Childhood” represents a marked departure from your earlier work with porn, as you turned your lens onto scenes of your adopted city and especially on your daughter, who figures into much of your work since her birth. How did this shift occur?

It happened in a really natural way. It was an outgrowth of my everyday life and where I was. I was in Berlin and taking pictures of Carmen’s kindergarten class, and Klaus Biesenbach, who was then a very young emerging curator, saw them and wanted to show them. He said, “Let’s call it ‘Berlin Childhood’ after Walter Benjamin’s memoir Berlin Childhood Around 1900. People will make the connection.” After that I thought to myself, “Maybe I should read those texts.”

There was no real English translation at that point, and it’s not easy German—lots of wordplay, that sort of thing. The text is written with a kind of montage technique, because Benjamin was really interested in cinema and photography. He would cut from one scene to another, or do panning shots or close-ups. I’d be reading a text and think, “I’m really not following this. He was just in a swimming pool, and now there’s a red light district.” I had a friend, a biologist whose daughter was Carmen’s best friend, who I asked to help explain the text to me in German that I could understand. She and I started working together a lot.

I was only there in the summertime, so for four months of the year I tried to shoot everything I could, to internalize the text and carry a camera with me all the time so if I saw something that fit the text I could just photograph it. I wanted to find images in contemporary Berlin that spoke to the images in Berlin Childhood, and I decided to only photograph contemporary equivalents. If Benjamin mentioned something like the Kaiserpanorama—an early precursor to cinema viewed through stereoscopic glasses—I would try to find a virtual reality club or something like that.

One day I was at the museum with my daughter and her friends, and we heard the little bell that tells you that the photographs in the Kaiserpanorama are turning, which Benjamin describes in his text. Carmen and her friends were so excited—they ran over and were looking through the holes. It was so beautiful, and I thought, “Why not photograph this?” Even though it’s something from the past, it’s still here. It has a different sort of existence now, as a relic, but that’s what it is in contemporary life. Then I really discovered that Benjamin was really interested in these kinds of objects from the recent past that kind of fossilize time, that time congeals around.

Kaiserpanorama, 1993

Kaiserpanorama, 1993

What about your other Benjamin project, The Angel of History? It’s very different from everything else that you’ve done.

Benjamin is really a writer who writes in images. That’s something that I learned about him. I’m not a sex expert and I’m not a Benjamin expert, but I learn about these things by working with the images. I work with them and let them work on me as well. After I finished “Berlin Childhood,” I found the last text of Benjamin’s “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” which he wrote in 1940 shortly before he committed suicide. There’s a section in this essay that is based on another image, Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus from 1920, which he owned. It was kind of meditative focal point for Benjamin, and he talked about it as the angel of history looking back at the rubble of civilization.

I decided to make a picture out of this picture. It was the very beginning of Photoshop for me, so I tried Photoshopping this montage. I realized that this pile of rubble that Benjamin is talking about could be so many things that it was in a way all of culture, all of civilization. I started making a lot of different photomontages, but I thought that since it was really a moving image, I should make a movie out of it, with the angel blowing backwards and the pile getting bigger. That was a bone-crushing project. It took years to do. Luckily I found this wonderful filmmaker named Lisa Crafts to make this five-minute film with me. It’s since been included in the European Month of Photography and a few other shows.

Walter Benjamin had four granddaughters. His son Stefan fled to London during the war with his mother Dora, where he ended up marrying three times before he died. His second daughter Chantal had seen my work at some shows and came to Berlin to learn more about her grandfather—that whole intellectual tradition had been lost for her. We became friends there, and she settled in Berlin as a social worker. She works with Turkish and African families, and she’s quite poor. I started filming her and her daughter, always with the thought of “Berlin Childhood” in the back of my head. I have a lot of footage, and I’ve decided to make a movie. I’ve asked Francis Schultz, the artist from Cologne, if she wants to collaborate, and I think that’s what I’m going to work on during my sabbatical next year.

Spree, 2013

Spree, 2013

Your photo series “Who Am I? What Am I? Where Am I?” also features your daughter and her friends, this time with their faces painted or otherwise altered by artists including Mike Kelley, Jutta Koether, John Baldessari, and about 80 others. How did you find yourself working with children on this level?

“Who Am I? What Am I? Where Am I?” also started in Berlin. I have conflicted relationship with Germany because my family fled in ’39, which is perhaps also a subtext to “Berlin Childhood.” I had brought some face paints to my daughter’s kindergarten glass as gifts. One of the teachers was an African-German woman. I’m German-Jewish, and it was a particularly xenophobic moment then, in ’93 or so. She and I would often discuss how we felt in Berlin. One day I picked Carmen up and her teacher had painted all the children’s faces. Everyone was so happy, and I felt like I should just do a show with her. She should paint the children, I’ll photograph them, and it will be an act of reconciliation for both of us.

That’s what I did that summer, but when I came back to New York it didn’t seem like such a gesture would have any relevance. I was still shooting the children at Carmen’s elementary school—I’d take photos at the winter fair and put them up on the bulletin board for them to take home. There are still people I meet now who say they still have those pictures up on their refrigerators. Children love to be photographed with their faces painted, but I wondered who would ever take this seriously. A mother painting butterflies on her daughter’s face? It’s beautiful, but, you know….

One day, I was having dinner with Kiki Smith, and she had all these henna designs on her face. I asked her if she would want to paint that on a child’s face. She said, “Actually, I have an idea.” She came over the next day with these rice paper tattoos that she had made and tattooed Carmen’s face with them, and that was the beginning of “Who Am I? What Am I? Where Am I?” It’s a kind of funny trajectory, from Berlin into New York. Not all of the artists I worked with wanted to paint a kid’s face, so the project started change and evolve as other artists came in.

Mike Kelley-Carmen Rosenberg Miller, 1997

Mike Kelley-Carmen Rosenberg Miller, 1997

In some ways, this series is one of your most challenging, insofar as it incorporates children into what some critics have called sexualized imagery. What’s more, many of the photos are of your daughter. Can you tell us a little more about the process of making these images?

It’s funny. I worked with porn images in part for their transgressive qualities, but in the end they actually seem very formal, whereas with the children I was thinking of this as a really good-natured project. So I was surprised—and then of course understood—how challenging and maybe questionable some of the process was. When I first showed this work in ’98, I got this really scathing review from Robert Mahoney about how any mother who would allow Mike Kelley within 10 feet of her daughter should be in therapy. Maybe he’s got a point, I don’t know [laughs].

Carmen still has real issues about that image that Mike and I did together. Carmen was about 7 years old and knew Mike, so when he came over to do the photographs she put on her best dress-up gown for dinner and was really excited. Her friend Joe Siena, James Siena’s son, was there too. Mike told me he wanted to paint her like a goth girl, but when she went in the bathroom and saw what she looked like she come out crying. What I hadn’t really thought about at the time, because I was so preoccupied with lighting and everything else, was that Mike had painted cleavage on her, and that she looked kind of battered.

At that moment, I was definitely the photographer and not the mother. I was thinking, “If I don’t shoot this, I won’t have it. I can make the decision about whether I want to keep it or not later on, but I need to shoot it.” I begged Carmen to let us shoot one roll of film, and when we were finished she was really crying, tears rolling down her face. I told her to go in the bathroom and wash her face. She came out of the bathroom wearing my dark sunglasses and started to really vamp it up for us. We ended up shooting another roll of film, and then she took off the glasses and was kind of happy. After that, we had dinner and everything was fine.

Neither Mike nor I had really understood what had really happened—we were just happy we got three rolls of film out of it. Carmen wrote about this experience years later, for her college entrance exam. She’s written about it since then too, so I know it’s still something that she’s contending with. She said that it had something to do with her sense of who she was. When she looked in the mirror she didn’t recognize the girl she saw, but she knew it was her. It contradicted her sense of a fixed identity. When she put the sunglasses on, she covered up what she didn’t like and sort of took control. That made her feel that she did have some agency when it came to how people saw her or who she was or thought she was.

Laurie Simmons-Lena Dunham, 1997

Laurie Simmons-Lena Dunham, 1997

I think it’s an example of the way that a lot of children had agency in these pictures that Bob Mahoney didn’t see. I did a photograph with Laurie Simmons and Lena [Duham, Simmons’s daughter], and Lena always says it was her directing debut. When she was flossing her teeth at night, she’d floss down under her lips to make herself look like one of Laurie’s puppets. That’s what she wanted to do. We had Laurie dress up in this white suit with these black gloves and stand behind Lena holding the floss. When Bob Mahoney saw that, he said that Laurie was so carried away with her own ego that she’s turned her own daughter into one of her puppets, but that’s really not the way it happened.

The children weren’t just blank slates that these artistic egos were getting projected onto, but of course there is that aspect to it. When artists are given the opportunity to play, they often do their kind of work. They play with their trademark, with that thing that identifies them as an artist. There was a lot of stuff going on with this series that I hadn’t really anticipated, but that’s the best thing about working as an artist—to create these more complicated scenarios for yourself.