After fleeing Nazi-occupied Lithuania in 1944 and spending the next five years bouncing between forced labor and displaced persons camps, Jonas Mekas and his brother Adolfas emigrated to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to embark on a half-century sojourn into the heart of avant-garde cinema and the psyche of artistic community. Mekas helped to found Film Culture magazine in 1954 and Anthology Film Archives in 1969, central components in the flowering New York art scene that saw everything from the Beat Generation to Pop Art and beyond come to fruition. Along the way he met and filmed many of the most interesting and influential characters of the 20th century, including Salvator Dalí, Jackie Kennedy, Andy Warhol, and Yoko Ono, assembling pieces of the footage—or "notes," as he calls them—into idiosyncratic, diaristic pictures.

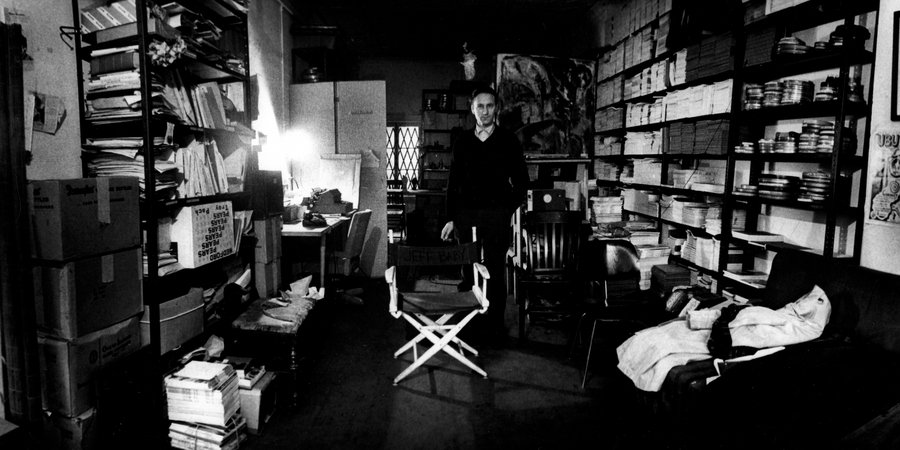

At 92 years old, Mekas maintains a mischievous twinkle in his eyes that sharpens into a laser beam as he makes a joke or declares his position—a pointed reminder that you are speaking to one of the giants of 20th century art. Artspace visited Mekas in his Clinton Hill studio, where, alongside mountains of books and one very friendly cat, we spoke about his tumultuous early years in postwar New York, a heady time for avant-garde cinema. Read on below, and stay tuned for the second half of our conversation next week.

You were 17 when Soviet soldiers invaded Lithuania in 1940, and 18 when the Nazis replaced them. You fled your hometown with your brother Adolfas in secret, fearing persecution for your anti-Nazi writings, and later wound up escaping a forced-labor camp only to spend the next several years moving between displaced-persons camps before getting shipped to New York in 1949. When, in this almost unthinkable tumult, did you first realize that you wanted to be a filmmaker?

There was no moment when I realized. Like in every art or in any other activity or profession, it’s a slow fading-in. The crucial moment for me was landing in New York, where I could find a job and have some money to buy a camera and film. Until then it was my postwar displaced-person period, where I was interested in cinema and poetry but could not do anything myself.

I landed in New York in late 1949, which opened all the possibilities. New York was already moving into maybe its most productive period, the ‘50s and ‘60s—I had landed at a very good moment in time.

Many of the people that you met at that moment have since become central to American art history. What was it like to experience the creative ferment of this time?

It was happening in every art: John Cage’s music, drastic changes in the theater moving into the advent of the Happenings, et cetera. The classic period had ended, and new styles and content started coming in.

What do you think it was about that time specifically that proved so fertile for artists and innovators?

Many have tried to theorize and rationalize this postwar period in terms of Eisenhower or what was happening in the world or in America, but there’s no real answer. Look at all the art movements—Futurists, Dadaists, Surrealists. There are certain times or circumstances where everything comes together to produce this moment. It was the same here in America, where Abstract Expressionists developed at a very specific time.

My thinking is that the classical approach, the old styles and content, came to an end somewhere around 1945, 1950. There was a need to move somewhere else. Sensibilities began changing, technologies were moving forward faster. Look at architecture, Buckminster Fuller’s buildings. All of these new ideas begin to enter the culture at this time, and only now are we realizing the effects of all that.

Was there a sense at that early stage that you or the friends and collaborators you filmed were up to something important?

No, but there was excitement. Each one of us was obsessed with doing what we were doing and going intensely in that direction, whatever that direction was. None of us thought that our work was important, that it might affect anyone or continue on past us. That is not why one does anything in science or art. One just does it, without thinking. Otherwise, one would be in a later, conscious stage where one would do things for effect, for the future [laughs]. That is not how life is.

What was the market for these kinds of films like in the early years?

There was no market, and I don’t think there is a market for poetic, non-commercial, non-narrative cinema. There is no market, just like poetry. Poetry and literature has no market—only prose, novelistic literature has a market. You don’t find poetry in the airport bookstores. It's the same endeavor with film.

When I came to New York, there were three or four film societies—Cinema 16, the New York Film Society, a couple others—but then five years later there were already six or seven. It grew very, very fast as we moved towards the ‘60s. It was aligned with the changes in film technology—the rise of cinema verite and portable equipment, et cetera. It changed rapidly, but it was still very limited. That’s why I began organizing and curating screenings in ’53, in a place that nobody knows now. It was the first downtown gallery, called Gallery East, on Avenue A and Houston. It was a cooperative gallery of local artists, and they said “Why don’t you show some films here?” That’s where I began my screenings in ’53.

Your screenings of avant-garde films are now recognized for introducing many people—including a young Andy Warhol, who you helped to film Empire in 1964—to a certain kind of experimental cinematic idiom. In some cases, though, your events proved too radical for their time, as exemplified in your arrests on charges of obscenity for a then-radical double bill featuring Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour. What can you tell me about that event?

The first arrest was at the St. Mark’s Theater on the corner of Bowery, and the second was at the Writer’s Stage on 4th Street. This was in March ’64. It was connected to licensing—that was the excuse that they used. Every film shown publically in New York had to be submitted to the license board, where they looked and said what had to be cut out. Many, many films had to trim something out. There were certain parts of the human body that you just could not show, and they wouldn’t give you a license if you did show them. If you showed without a license you could be arrested and the film could be seized, and then you would have an obscenity case. That’s what happened with me. I refused to submit films for licensing—I did not submit any, I just screened them.

While I can imagine your answer, I have to ask: why did you to forgo this legal requirement?

Who are they to censor, to pass judgment on the works of anybody? Who are they? Self-appointed censors. To me, it was absurd, illegal, and stupid. I could not accept that.

Of course, my case was not the only one. Three or four years later licensing was abandoned in New York, because there was so much discussion of the cases in the press. The same applied to Lenny Bruce, to cabaret and cafes, to humorists of that time, period. You could not make jokes on certain subjects.

You're perhaps best known for starting Anthology Film Archives. What other organizations did you have a hand in starting?

In the ‘50s I had Film Forum, then the Filmmaker’s Cinematheque in the ‘60s, which then led into the Anthology Film Archives that opened in 1970. There was a series of different organizations for different reasons.

Even as you’ve worked to create your extensive body of work over the past 60 years, you’ve put just as much energy into building organizations and outlets for other artists and filmmakers. What do you see as the importance of creating groups that serve the artistic community?

It’s a way of directly supporting their efforts, creating something like the Filmmaker’s Cinematheque so they could screen their films or the Filmmaker’s Cooperative so they could distribute them. Even writing my "Movie Journal" column in the Village Voice was part of this, in that I was bringing their work to the attention of others. That’s in my nature—if I like something, I want others to know about it. If I like a film, I want others to see it. To me, it’s normal to do that. It’s nothing special.

You’ve cultivated a very specific visual style for your films over the years. How would you describe your process?

I just keep notes on life around me. The term is a diarist, usually, but I make notes. I don't make films, so to speak. I just film. Later I put some of those notes together, organized either thematically or in general about my life, and I release them. I’ll collect all the material, let’s say on Andy Warhol, and I release them as Scenes From the Life of Andy Warhol, et cetera.

How do you go about stitching these filmed notes together? What are you thinking about as you’re going through and editing?

Sometimes it’s thematically, when somebody asks me to do something for a special occasion. That’s how Scenes From the Life of Andy Warhol came into existence. The Pompidou had a retrospective on Warhol, and they asked if I had any footage of him to be presented at the same time. I said, “Yes, sure I have some,” so I put it all together and that was how that film originated. The same happened with Scenes From the Life of George Maciunas, on Fluxus and the collapse of the Soviet Union. It’s a six-hour long movie, I had all the footage, so I just strung it together for the occasion. Now I’m doing the same thing for a show about the Velvet Underground that goes up in Paris in 2016, so I’m collecting all my footage related to that period, to Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. This is a huge exhibition that involves a lot of people, and my film will be presented as a part of it.

I have a five-hour long movie about my life, As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty. That came up in Avignon, France, where the theme for one of the festivals was “beauty.” They asked me if I had any film on that subject, and I said “If you give me money, I will make you a movie on that subject, because that’s what I think what I film is all about.” They said they would cover all expenses, so I did it thanks to them.

Actually, Buffalo, New York, sponsored the very first film that I finished in this diaristic style, Walden from 1968. They had an arts festival, with music by John Cage and plays by Edward Albee, and they said they wanted have a film at the festival also and asked me to do it. I said yes, and they sponsored the finishing of Walden.

For the last 20 or so years you’ve been making prints from bits of your film and video works in addtion to your ongoing film and video projects. What prompted this shift to making physical objects?

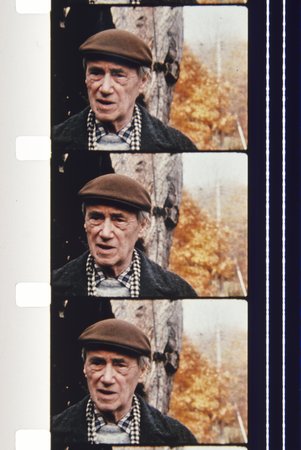

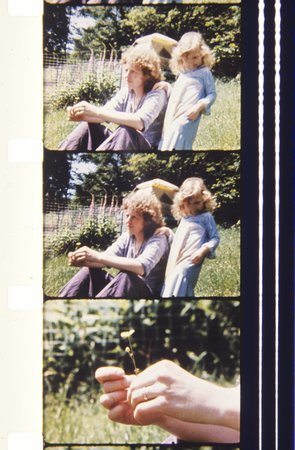

I will tell you how it originated: when I put two filmstrips together, the ends of those strips are sometimes damaged or have dirt in them. I usually cut off three or four frames and throw them away. What I cut off these strips do not exist in films, since I cut them out of the finished product. At some point about 20 years ago I looked at those little bits and said, “Why am I throwing these out?” I realized that I could make prints—they are like photographic negatives, or in this case positives.

When I grew up, my older brothers and my father used to slaughter a pig, for Christmas or whatever. My mother used to dissect it and put it in pots, and she used everything. There was nothing thrown out. She made rillettes from the scraps—it was terrific. I said to myself, “My mother used everything, and I’m throwing these on the floor,” so I began collecting and studying my own scraps to make prints. Later, I also started to photograph stills from the middle of the shot, not only the ends. Since I use a lot of single-frames in my films, very often in the span of five frames there is a lot of different activity. A lot can happen even between three or four frames, so I began printing them and exhibiting them.

You’ve worked with so many notables over the years, from your storied collaborations with Andy Warhol to your employment as the Kennedy children’s private film tutor. What was it like working with people that are so recognizable yet mysterious to the public?

I did not know them in their public lives—I knew them only in private, so they were like anybody else in their own situation. Whenever people ask me about these people—John Lennon, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, the Kennedy’s—I always say that they’re like anybody else, because I knew them only as people, privately, not how they are perceived in the public eye. It’s a completely different relationship, and it becomes normal. There’s nothing much to say.