At a panel discussion at Phillips earlier this month, the artists Lyle Ashton Harris , Cary Leibowitz (a.k.a. Candyass), Marlene McCarty , and Deborah Kass debated whether there is such thing as "queer art," or only "queer artists." These four emerged out of a time when queer culture existed outside of (and in opposition to) the mainstream; when making art that proclaimed a marginalized subjectivity required carving out space and staking a claim. In 2019, these artists discussed how the landscape has changed in the decades that followed; as mainstream culture has become more inclusive of queer culture, and queer culture is increasingly embracing an intersectional, more inclusive approach to identity, can we even define what "queer" art looks like? These are exactly the types of questions that rattle between the covers of Art & Queer Culture , Phaidon's unprecedented survey of visual art and queerness from the late 19th century to the present, and the topic of the aforementioned panel discussion at Philips.

The second edition of

Art & Queer Culture

is available on Artspace for $39

The second edition of

Art & Queer Culture

is available on Artspace for $39

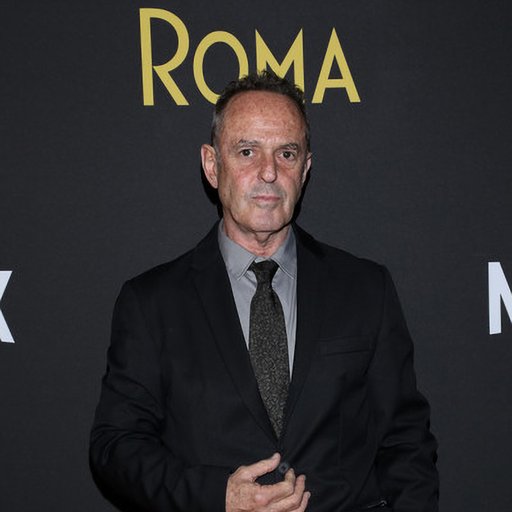

First published in 2013, the beautifully illustrated book has been updated to include art and artists of the current moment in its second edition, published earlier this year. A group of new contributors joined the primary authors, Richard Meyer and Catherine Lord , in emphasizing the global sweep of queer contemporary art and the newfound visibility of gender non-conforming artists. The book will be the subject of a second panel discussion—this time at Frieze New York on Randall's Island on Saturday, May 4th—that promises to be both informative and illuminating if the first iteration is any indication. Co-produced by Matches Fashion, the discussion will include panelists Sheila Pepe and Gio Black Peters , two artists featured in the book, and Richard Meyer , co-author of the book and a Professor in Art History at Stanford University. Meyer is also the author of Outlaw Representation , a book about censorship and homosexuality in American Art, and What Was Contemporary Art? , a book in which Meyer "reclaims the contemporary from historical amnesia, exploring episodes in the study, exhibition, and reception of early twentieth-century art and visual culture."

Here, in an interview perviously published on Phaidon.com , Mat Smith speaks with Meyer about how the subject of queer culture has changed since the first edition of the book was published, about the globalization of queerness, and about the future of queer art.

To attend to the panel discussion at Frieze on Saturday, May 4th from 2:00 - 3:00PM, you can RSVP here.

Broadly, is contemporary queer art and queer culture now less about protest and more about sexuality than when the book was first published?

The politics of queer culture have changed since 2013 but not in ways that are necessarily linked to protest vs. sexuality. I am thinking about the increasing visibility of the struggle for transgender rights and lives (and the threats posed by Trump’s military ban, for example, or the opposition to safe, gender neutral public restrooms) as well as the ongoing persecution of queers—and queer artists—within a global context, including the shutting down of an “African Queerness” exhibition at Dak’art in 2014, and the multiple arrests of Ren Hang in Beijing, who later committed suicide. Making art about queer sexuality is itself a kind of protest—pushing the boundaries of what can be seen and imagined in the public sphere.

What are the recent changes in the narrative that make queer art and queer culture interesting now?

Queers and the art they produce increasingly subvert traditional gender binaries of male and female while also troubling whiteness as the default category of racial identity within Western culture. As the last section of the book makes clear, queer artists also resist being confined to or identified with any one medium.

How has the definition of art and queer culture changed and what wider forces have played a part in that?

We chose the word ‘queer’ precisely for the way in which it is always changing in relation to the norms established (and imposed) by mainstream culture. The book argues that contemporary queer culture draws on the legacy of earlier moments in non-normative gender and sexualities. We challenge the idea that queer art moves forward in a linear fashion by considering its recursive and memorial qualities.

The book is an international survey; what countries are coming to the fore?

What we’ve discovered is that queer culture is highly site-specific. While it’s crucial to think globally, it’s equally important to realize the limits of one perspective and the particularity (and in our case, privileges) of the location from which we look. Speaking very broadly, in fact continentally, there are more Asian, South American, and African artists emerging within queer contexts but the visibility of these artists is often met with backlash, censorship, or criminalization. Finally, as sex and gender operate differently in different national, religious, and ethnic contexts, so queer art and culture will necessarily mean differently too.

Is there a particular medium snapping into focus?

Today, there is no way to separate visual art in say painting or sculpture from video, performance, photography, and mixed media. Contemporary artists—and perhaps contemporary queer artists in particular—do not feel bound by medium or genre. Increasingly, artists are using the internet to build exhibition platforms and different forms of public visibility. Cassils’ work, for example, is most accessible on their personal website, not through their gallery representation. The web allows for increased self-representation or self-fashioning, and these two ideas have been central to queer culture for decades. It’s free to show your work on Instagram or do a performance in public space. These are some of the tools available to younger queer artists.

Is there a new work in the book that you think will become iconic in the years to come?

The book is invested in queer culture as a collective and ongoing project rather than the celebration of individual artist-heroes. So maybe one way to answer this question is to point to a couple of recent works that themselves bridge different moments. Phranc’s sewn and painted cardboard Red Dress (Please Don’t Make Me Wear this Dress) for example, recalls the conventional femininity she was forced to embody as a young girl. Cardboard men’s shirts and tomboy trunks from the same series celebrate the 'butch armor' Phranc adopted as she grew up and eventually came out.

The sculptures therefore bridge not only past and present but also the journey across gender codes that queerness often entails. And speaking of gender travel, I would also nominate the Museum of Transgender History and Art (MOTHA) as a project that imaginatively records—or curates—the trans past, from a replica of a shot glass thrown by the Black street queen Martha P. Johnson at the Stonewall Riots in 1969 to a 1990s t-shirt imprinted with the words 'Transgender Menace.'

As Cyle Metzger, a new contributor to Art & Queer Culture , puts it, MOTHA "simultaneously looks backwards and forwards in a way that resists establishing a fixed institution." On one hand, the project is critical of the exclusion of trans people from LGB historical narratives and of the limitations that any static institutional model places on evolving understandings of the queer past. On the other hand, the very reason MOTHA retrieves history is to foster what has been called "trans futurity, or a space and time of expansive possibility for trans existence." We hope this book likewise engenders an awareness of non-normative art and sexuality since the late 19th century as well as a resource for creating dynamic possibilities in the queer future.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Jess T. Dugan's Graceful Portraits Capture Transgender People As They Age

Dandies, Butts, And The "Homesse": 5 Examples Of Queer Art Before Queerness "Existed"