For Anicka Yi , the studio is a giant—and often pungent—petri dish. As an official visiting artist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology , Yi has been collaborating with synthetic biologists on projects that extend her futuristic sculptures into the realms of science and scent. With their help, she recently tapped her own network of female writers, curators, and fellow artists to generate a potent "collective bacteria"; she is also working on a massive, menthol-infused pond for her upcoming show at MIT (opening in May).

Following up on her breakout solos at the Lower East Side gallery 47 Canal , where she pushed Postminimal sculpture into new sensorial realms with substances such as honey and oxytocin, Yi is currently taking over the Chelsea alternative space T he Kitchen with her show "You Can Call Me F." In this ominous and dimly-lit installation, quarantine tents open to reveal scent diffusers, sculptural objects and bowls of mysterious liquids (some of them fostering Yi's bacterial concoction.) The show, curated by Lumi Tan, identifies and associates two troubling social trends: the fear of contagion and the dismissive response to groups of women. Yi took a break from the lab to talk to Artspace 's Karen Rosenberg about learning to love germs, the art world’s fear of the feminine, and the elusive scent of the Gagosian franchise.

How and why did you start to work with scents?

I’ve always been looking to reorder the senses, because I felt that we in the West have been overly dominated by the ocular sense. Everything is about looking—we have such ocular fatigue. I know I do. I go online and I’m not even looking anymore, because there’s just this proliferation of images. We have these tools open to us, and we’re not using them. I believe we’ve lost our empathic core because we’ve neglected these other senses, like smell and touch and taste.

Smell is a form of sculpture, because it has a lot of volume. Also, it collapses the distance that painting has built into it—it’s like, "Look, but don’t touch, and keep your distance." I want to draw the viewer in further and have the viewer participate by having to be there physically to smell the work, rather than just transmit it through JPEGs.

What led you to team up with chemists and biologists?

It was a sheer necessity. A lot of the material I was working with, like glycerin soap and fried flowers, was challenging to stabilize. So I started soliciting chemists and chemical engineers to get some advice on how to work with these materials that were highly reactive and often would reject each other. I was flat-out ignored, mostly, until I got this residency at MIT. It really opened the gates for me, to have the opportunity to develop relationships with some of the top researchers and scientists. And then the biology started to become more tangible.

Why work with bacteria?

I’m interested in bacteria because it’s the genesis of life. It also plays on a lot of our anxieties about cleanliness and hygiene. And there’s so much good bacteria out there, whether it’s in the form of fermentation and food or bacteria that helps your immune system.

Describe the process of coming up with the “collective bacteria” in the show, which is based on samples from 100 different women.

It was a lot of legwork. I would walk around with q-tips and Ziploc bags and a sharpie, wherever I went, and just get samples on the fly. I noticed it was challenging to get 100 women. If it had been 100 guys, it probably would have taken half the time. Guys tend to gather in clusters; with women, we really had to go all over the place. That was very telling. There’s a lot of anthropological social experimentation that we were able to glean from the fieldwork. It’s not just the biology. It was also due to all the interesting places that the culture samples came from, which I also think is very much a part of the work, that were very gender-based.

What were some of these places?

Vaginas.

Oh! And so what does the viewer encounter when they enter the show?

There’s a minimum of two different kinds of smells. There’s the physical, raw form of the agar and the bacteria growing. It’s not necessarily intended as a smell piece, but it’s kind of implicit. The notes are very pungent, definitely something that’s bodily, musky-husky. Parts are very sharp and sour, but very warm and voluptuous notes.

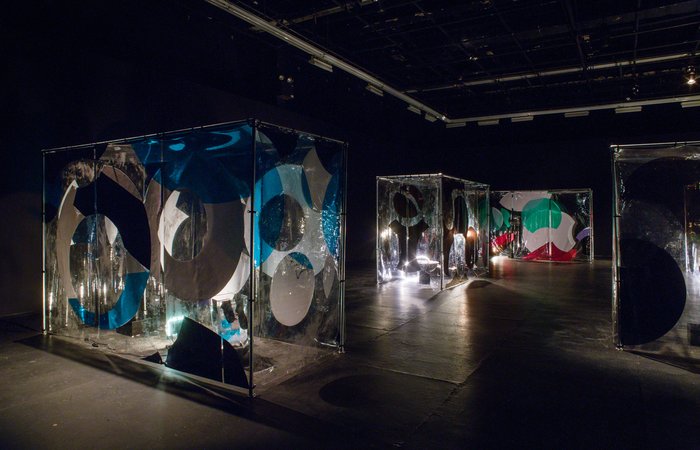

Anicka Yi, You Can Call Me F, installation view, 2015. Photo by Jason Mandella.

What about the male scent in the show, described in the press release as "the almost imperceptible odor of the ultimate patriarchal-model network in the art world, Gagosian Gallery"? How did you bottle that?

I did an air reading—I went into the space with this metal canister that looks like a basketball. It it takes about a three-minute read of the air. It happened to be during the Urs Fischer show, and it was quite comical because the gallery attendant was definitely not having it. He was like, “You can’t do that in here!” And I’m clearly stalling for the three minutes I need to take the read. I want the surveillance video—it should be really funny.

How would you characterize that scent?

In places like Gagosian gallery, or any gallery, for that matter, it’s about the absence of smell. There shouldn’t be an odor. In the West, we equate power, especially power structures, with the absence of smell, because we are so repressed about smell. If you think about the president of the United States, you should not be thinking about a smell. Finance, banking, government, high-end retail, should not be associated with any aroma whatsoever. That’s what I wanted to capture, an antiseptic, non-smelling place. The bacteria smells a little more human, if you can say that, than the Gagosian smell. But blended together, it just kind of balances out.

Are you making a kind of probiotic for the art world, something to correct its gender imbalances?

I don’t see it as a probiotic so much as a living organism. There’s very, very little control you can have with it, and at a certain point I had to give in and let go. It’s powerful stuff, not to mention the bacteria in the space itself. The Kitchen is a really old building, and a lot of interesting colonies were developing in the environment.

Can you talk about the sculptural components of the installation? The quarantine tents, for instance, seem to relate to the recent Ebola outbreak.

It’s a global anxiety, and it’s not going away—you might be able to eradicate one virus but then another one pops up. Everyone’s using hand sanitizer and creating a supervirus that’s going to be resistant to any chemical we attack it with. My assertion with this show is that we just need to calm down a little bit, take a look around at what’s happening with these bodies. With less hysteria, we can learn a lot. It goes back to the reordering of the senses—I think that we’ve completely betrayed a lot of our wisdom and intellect by privileging and prioritizing just one sense that dominates all others.

Anicka Yi, Detail of Your Hand Feels Like a Pillow That's Been Microwaved , 2015. Vinyl, steel pipes, metal bowls, beeswax, dried shrimp, glycerin soap, hair gel, metal pins, seaweed, foam, plasticine, pigment powder, worklight. 122 x 78 x 50 inches. Courtesy of the artist and 47 Canal. Photo by Jason Mandella.

What about the elements inside the tents: motorcycle helmets, bowls of agar and bacteria, assorted other substances like dried shrimp and lizard eggs….

The content has a lot of the sculptural vocabulary I’ve developed in the past five to six years. You have perishability, transparency, embeddedness. The bowls, for example, I first made in 2009. I refer to them as stomachs, because of my ongoing conversation about metabolisms—how we are metabolized in systems and we willfully metabolize ourselves and others. I refer to a lot of my sculptures as stomachs. The stomach is the second brain, and it’s the all-knowing. It’s gut wisdom.

Then you have the helmets. I’ve always considered smell to be a form of cannibalism, because you are able to ingest somebody when you smell them. These helmets function like heads on spits.

You often use food smells and cooking techniques in your work; the centerpiece of your upcoming show at MIT, for instance, is a mentholated pond inspired by a dish you had at Ferran Adria ’s elBulli.

I don’t necessarily privilege food over other smells. It’s a delightful coincidence that when you fry inedible flowers in tempura batter it’s going to smell like French fries. Every time I do an installation like that, people are like, “When’s lunch?” But it’s about the narrative for me. I can’t make an exhibition without having the narrative first. I don’t work in this hermetic, formalist way—I need a story to tell.

The story, in this show, seems to be the societal response to groups of women: the idea that female networks are contagious, or unhygienic.

It comes from a very real place—my own experiences, first and foremost. There’s a lot of stigma, a lot of conditioning that women are not meant to gather—these derogatory phrases about girls’ night out, hen night, whatever you want to call it. Women getting together is seen as threatening, so it’s diminished into something frivolous. I was frustrated that I wasn’t seeing more females helping each other in this very aggressive, competitive place in the art world. Rather than point fingers and serve out indictments, I wanted to talk about why that exists.

You’d think the art world would be a more enlightened, progressive place.

There are predominantly female students, and yet very few stick it out. A survival mechanism kicks in where you have to align yourself with power, and this is why you gravitate towards the males. You tone down your femininity, or create an avatar that’s more masculine.

I’ve also been frustrated with a lot of sexism in formalism. It’s like, “Throw some metal on that and make it more masculine, and that will make it more powerful.” My work has been accused of being too feminine numerous times. It’s an unspoken trope: you’ve got to make it more macho, or it will not sell. Or it won’t be legitimized, it’s too vulnerable. You’ve got to make this cold, abstract, formalist work.

What about the wider professional culture, in which women like Sheryl Sandberg have become strong advocates for female networks? Has that had an impact on the art world?

I think there’s a lot of potential in the art world, because it’s so much about influence. People like being told what to like, what to look at. It’s so word-of-mouth. There’s a lot of power there, and responsibility. It’s about reorienting those reflexes.

You’re also, as you said earlier, trying to reorient our relationship to the senses.

Eyesight and vision are associated with knowledge, discovery, power and the masculine. Smell is shrouded in mystery, subjectivity, because it’s related to long-term memory. There are things about smell that are objective; they’re just really difficult to talk about. And anything difficult is put into a mysterious box, and therefore feminine.

I’ve always thought of my work as being on the precipice of a lot of discoveries that happen with smell. The day when we can smell a jpeg is probably just around the corner.