A self-described “empathetic disruptor,” the artist Brad Troemel has garnered avid attention for his hilarious projects that stake out a new kind of ground between the traditional gallery space and the funhouse-like marketplace of the Internet, using it as a staging ground to caricature the quirky operations of both. One of his best known early collaborative projects, the Tumblr-based art platform/meme generator known as Jogging , accomplished this by showcasing the cheeky ad hoc sculptures and Photoshop creations of Troemel and his friends as if the screen were a flat kind of virtual plinth; his Etsy store came at things from the other direction, using the craftsy online commercial forum as a place to present totally ridiculous, often perishable products—a Doritos Tacos Locos taco secured shut by a Masterlock, or a cluster of hot dogs, q-tips, and a SuperCuts pen wrapped up in a Livestrong bracelet—as if they were homespun products people might actually want. Bitcoins, it should be said, have become an obsession of his.

Recently, Troemel has begun showing more of his work in brick-and-mortar spaces, including solo shows at Tomorrow Gallery , Future Gallery , and now Zach Feuer , where he has a new show titled On View: Selections From the Troemel Collection . In the exhibition statement, a lengthy text artwork in itself, the artist introduces a new conceptual plaything: the notion of what he calls “CTAs,” or celebrity-turned-artists, whose art he labels as a “super good,” a product analogous to a “super food” that seethes with cross-contextual value. "Simultaneously an art object, a memorabilia item, and a hyper-intimate autograph," he writes, "CTA works (and super goods as a whole) are a highly potent bundle of commodities nestled within themselves, able to be extracted individually or allowed to appreciate in value simultaneously as a diversified portfolio."

To find out more about Troemel's latest lark, we caught up with him about "the supreme confidence game" of the art market, why he's included other artists' work in his new show, and (yes) Bitcoins.

Your work deals with different forms of valuation, whether directly as with crypto-currencies like Bitcoins, or more abstractly in terms of cultural capital. How do you approach these different value systems in your work?

I suppose I think of my work as a bundle. The idea is that the work is a binding factor for a number of different, potentially competing forms of valuation, whether it's vintage punk-rock apparel, organic foods, precious metals, whatever. I’ve included $4,000 worth of silver in paintings before at a show at the Fireplace Project. In this show at Zach’s you have complete sets of United States currency—every penny, nickel, or dime made from the inception of the coin all the way through to the current day—as well as other artists' work.

In some ways it’s meant to allude to the existence of art itself within a market—that art is a kind of commodity—but then to confuse that connection further through the introduction of other things. I think a lot about the fragility of the art market, about the ways in which it's this supreme confidence game, and how the introduction of these competing value systems becomes additive, in some ways meant to offset the risk associated with art being a pure confidence game. That is to say, a collector buying into these works isn’t merely buying a piece of my own but is simultaneously buying into some other potentially unstable or volatile market prone to booms and busts as well, whether that’s the crypto-currencies or the precious metals. Or maybe they’re buying a more solid investment, like U.S. coin sets or art by somebody else who’s probably more famous than me.

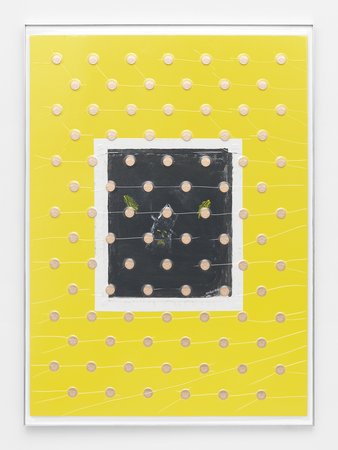

TBT, 2015 (Courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

TBT, 2015 (Courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

How did this fascination with value systems begin?

I think that this idea really came into focus for me when I was doing my Etsy store. I had a series of these Semiotext(e) books paired with physical Bitcoins placed on top of them that I would vacuum seal, which is itself a kind of allusion to the idea of compressing multiple precious materials together and mashing their various aspects into one. At the time, whenever curators would ask me to include works from the Etsy store in an exhibition I would always just tell them to buy the piece—the prices were so low that buying the piece for $20 or $30 was about on par with the shipping. After the show was over, they could just keep it.

I made an exception for this one series, the Semiotext(e) books and Bitcoins, to be exhibited at a gallery without being pre-purchased, because the value of the piece was something like four or five times whatever the face value of the Bitcoin was at that time. That was how I was doing my pricing for a while—I was just multiplying whatever the face value of the work was times two or three or four. In this case, the piece was anywhere from $500 to $4,000 for sale. Included in them were a one-Bitcoin piece, a 25-Bitcoin piece, and a 100-Bitcoin piece. The majority of these were purchased at the gallery, including the 25-Bitcoin piece, for somewhere in the ballpark of 3,500 bucks or so. This was just moments before the Bitcoin market took off, so within a month’s time the face value of the materials included in a piece that was sold for $3,500 rose to $35,000, and in some cases to a valuation higher than that.

As a side note: the physical Bitcoin is a more stable investment than the digital Bitcoin. The digital Bitcoin is a floating number subject to the confidence games of the market, whereas the physical Bitcoin is a sort of collector’s item. It’s scarce in the way that the digital Bitcoin is not, so over time the physical Bitcoin has managed to hold its value at about $900-$1,000 per Bitcoin whereas the digital Bitcoin’s price has dropped dramatically. That’s just a little nerd stuff.

FREEDOM LIGHTS OUR WORLD (FLOW), 2014 (Installation shot courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

FREEDOM LIGHTS OUR WORLD (FLOW), 2014 (Installation shot courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

So the price of the raw materials actually became higher than the listed price of the artwork?

I was kind of kicking myself for that, because I could have had a pretty big score there if I had just cashed in on the coin instead of selling it. But it created an interesting problem—it forced the collector to make a decision as to whether they were buying into me or into this crypto market, or some combination of the two. The decision that the collector has to make as a result of this—whether they’re going to cash out at $35,000 or if they’re going to wait—creates a really interesting conundrum for me. The show at Zach Feuer will include all of these different conundrums. It’s meant to be a bit of a riddle over time, as far as where the investment lies and where the value of the work lies.

In some of your works, you make a donation to a cause or organization and then incorporate it into the artwork. Do you see this as a kind of political engagement?

There are a few different ways we could go with that. Take the ant tanks at Tomorrow Gallery or the "ELF" paintings, which are dedicated to the Earth Liberation Front. I gave the ELF a bunch of money, and in return I asked that they give me an archive of different protest and propaganda leaflet images that they had produced over the years. That was a kind of exchange.

For the ant-tank pieces, I had these competing ant farms, each representing one of three different not-for-profits or charities or political action committees. The winner—the charity associated with the ant tank that displaced the most gel to the top of the tank—would get 10 percent of the sales of the show as a donation. I suppose that’s as far as my politics go, or rather those are my politics.

I read this study by a couple of Stanford economists and they concluded—surprise, surprise—that money has a larger influence than the democratic process. I’m surprised that more people haven’t lost their shit over this, or that there hasn’t been some sort of Semiotext(e) book or something written about it. This is a pretty big revelation in American politics.

LIVE/WORK, 2014 (Installation shot courtesy of Tomorrow Gallery, New York)

LIVE/WORK, 2014 (Installation shot courtesy of Tomorrow Gallery, New York)

What do you see as the next step, given this knowledge?

I guess you can take it two ways. You can get on the phone and try to strike down Citizens United and reverse this process, which I’m not sure I would be able to do myself. I do know that I can start giving money to different organizations that I believe in, in earnest.

Another theme in your work is ethical consumerism, often invoked through references to Whole Foods.

The tendency to choose “earth-friendly” products or those embedded with good ethical principles has gone so far that people can callously take advantage of it, through green-washing and stuff like that. I think that Whole Foods as a company, especially with its libertarian CEO, is a really good embodiment of this time. On one hand we’re using money to convolute and pollute the world that we live in, but on the other hand we’re simultaneously trying to use the other half of our money to cleanse that badness—to do good and to make up for it.

FREEDOM LIGHTS OUR WORLD (FLOW), 2014 (Installation shot courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

FREEDOM LIGHTS OUR WORLD (FLOW), 2014 (Installation shot courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

Are these exchanges with different political groups or organizations an honest expression of your politics?

Absolutely. I can’t really imagine a world where art can have a political impact on the basis of image, especially when the production and dissemination of images has become the primary fighting ground for politics itself. Art doesn't own image-making as a political form of protest anymore—politics owns images now. It seems to me that art, placed so conveniently at the nexus of vast amounts of wealth, could potentially have some impact in the prime motor of political change, which is now money.

You’re well known for your various essays and pseudo-manifestos, especially “Athletic Aesthetics” and “The Accidental Audience," both published in The New Inquiry in 2013, which expand on some of the ideas behind Jogging. What do you see as the relationship between your writing and your artwork?

I think that those essays follow from what my role was then, as a kind of producer or manager of art. I was writing those at a time where my main creative job—I had seven jobs at the time, to live—but my main job in terms of art making was managing Jogging. On the one hand, you can think of these essays as artist statements or something like that, but on the other hand they’re definitely infused with the work of other people. I largely talk about other people in these essays, about Jogging contributors and things that were coming in to Jogging that I was associated with but that I didn’t make personally. I was watching either the way that those people were producing, as in the case of “Athletic Aesthetics,” or how it was being received, where those posts were going and what types of people were engaging with them, as in the case of “The Accidental Audience.” Now that I’m mostly doing solo shows, the writing is a kind of intimate contextualization of what it is that I’m doing.

ELF Paintings (Installation shot courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

ELF Paintings (Installation shot courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

Your more recent writing has taken the form of mammoth press releases for those solo shows.

My press releases are usually in the ballpark of 1,000 to 2,000 words, so in that case it’s a very direct relationship to the work. I think each of the press releases has a different tone to it, whether you’re reading the one from Future Gallery or the one from Tomorrow Gallery or the one for the show at Zach Feuer. I try to create a key to the puzzle of the exhibition.

In terms of transparency and engagement, it’s important to actually talk to the audience that views you. As a viewer, I don’t gain much from extremely oblique, poetic, nonsensical artists’ statements. There’s so much information in the world that to further obfuscate something like art, something that’s already fairly cryptic itself—I don’t think does much in the service of the viewer.

The release for the upcoming show at Zach Feuer introduces the concept of the “super good” to describe certain artworks, especially those created by what you call CTAs, or “celebrity-turned-artists.”

A “super food” is one that does many good things for your body simultaneously. The “super good” is a play on words—it’s the idea that you can bundle commodities together. Art is not beholden to any one particular discipline—it can be philosophy or social justice work or pure aesthetic commodity or all these things at once. To bundle together these different aspects of art is to bring into being a commodity that is potentially greater than the sum of its parts.

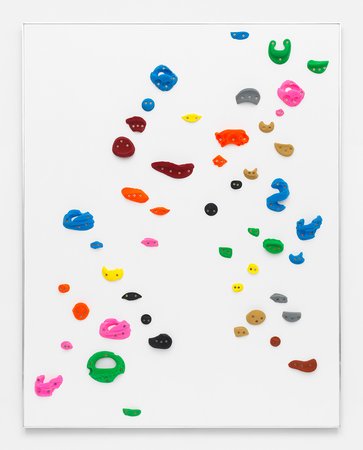

Wall Mount For Vintage Furby Collections (Mint Condition) #3, 2015 (Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

Wall Mount For Vintage Furby Collections (Mint Condition) #3, 2015 (Courtesy of Zach Feuer Gallery, New York)

What kinds of works did you bring into the gallery to illustrate this potential?

You’ll see a wide range of different types of value being bundled and nestled within each other. In terms of actual commodities, you have everything from raw lumber to cutting-edge technology like 3-D printed guns and drones to a wide range of currencies, everything from Bitcoins to Litecoins to complete United States currency sets to complete Chuck E. Cheese token sets.

On top of that, or rather underneath it, you have paintings and things done by celebrities that come from different kinds of fame: musicians, socialites, pro skateboarders, all types of different celebrities. You have couture clothing, like Vivienne Westwood’s clothing from the time when she was producing the clothing for the Sex Pistols to wear as an advertisement for their collaborative shop “Sex” in London, hence the name “Sex Pistols.” You have all types of different figurines, ranging from KAWS to Maurizio Cattelan to everything in between. There’s a lot of things in this show—lots of collections of mine and new collections that I’ve just recently started.