Nathaniel Mary Quinn has visions from which he makes representations of people he has known. His portraits are unorthodox, showing an emotional essence through masterfully rendered visceral fragments, sourced from magazines and personal photographs to portray Quinn’s memories.

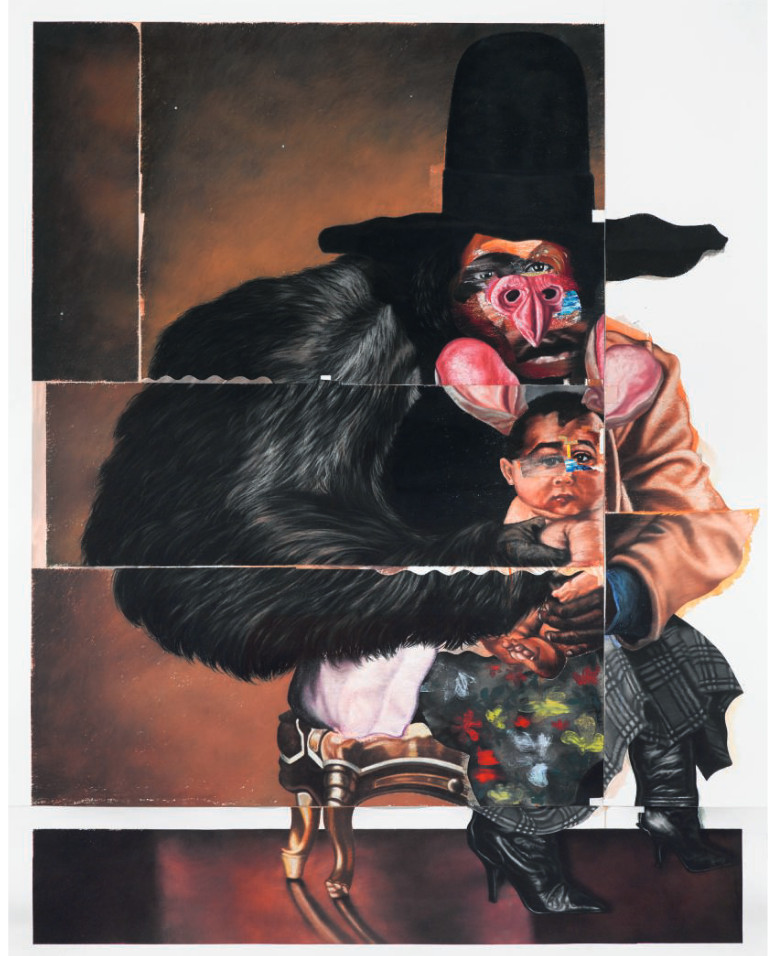

Big Rabbit, Little Rabbit (2017) portrays the artist as a small child cradled on his father’s lap, drawn on multiple sheets of paper to imply the memories are larger than life. The figures pose, seated on a regal ottoman, dominated by the dark furry gorilla arm of the father figure; unaligned jagged edges are jiggered across the sheets of paper, interrupted by scalloped design patterns, while a colorful infant blanket emerges to create high contrast. Big Rabbit’s supple mouth is pierced by the depiction of a plastic toy rabbit’s nose. Quinn’s father lacked a formal education and was unable to read or write, so to make money he would hop from one pool table to another, thus acquiring his sobriquet. Quinn became known as Little Rabbit, a term that emotionally connects him to his father’s betting skills to shield against the poverty of the drug-ridden projects of Chicago’s South Side.

His father taught Quinn how to draw, using thick telephone books, challenging each other to fill a book without erasing a line. Unexpectedly, feminine leather boots emerge from a checked grey on black kilt, symbolizing Quinn’s mother’s matriarchal support. Mary helped Quinn gain admission to an elite boarding school, but after his first month there she died. Returning home at Thanksgiving, he discovered the apartment where he had grown up was empty, and his father and four brothers had abandoned him. He was fifteen-years-old. He took her name at high school graduation to acknowledge her.

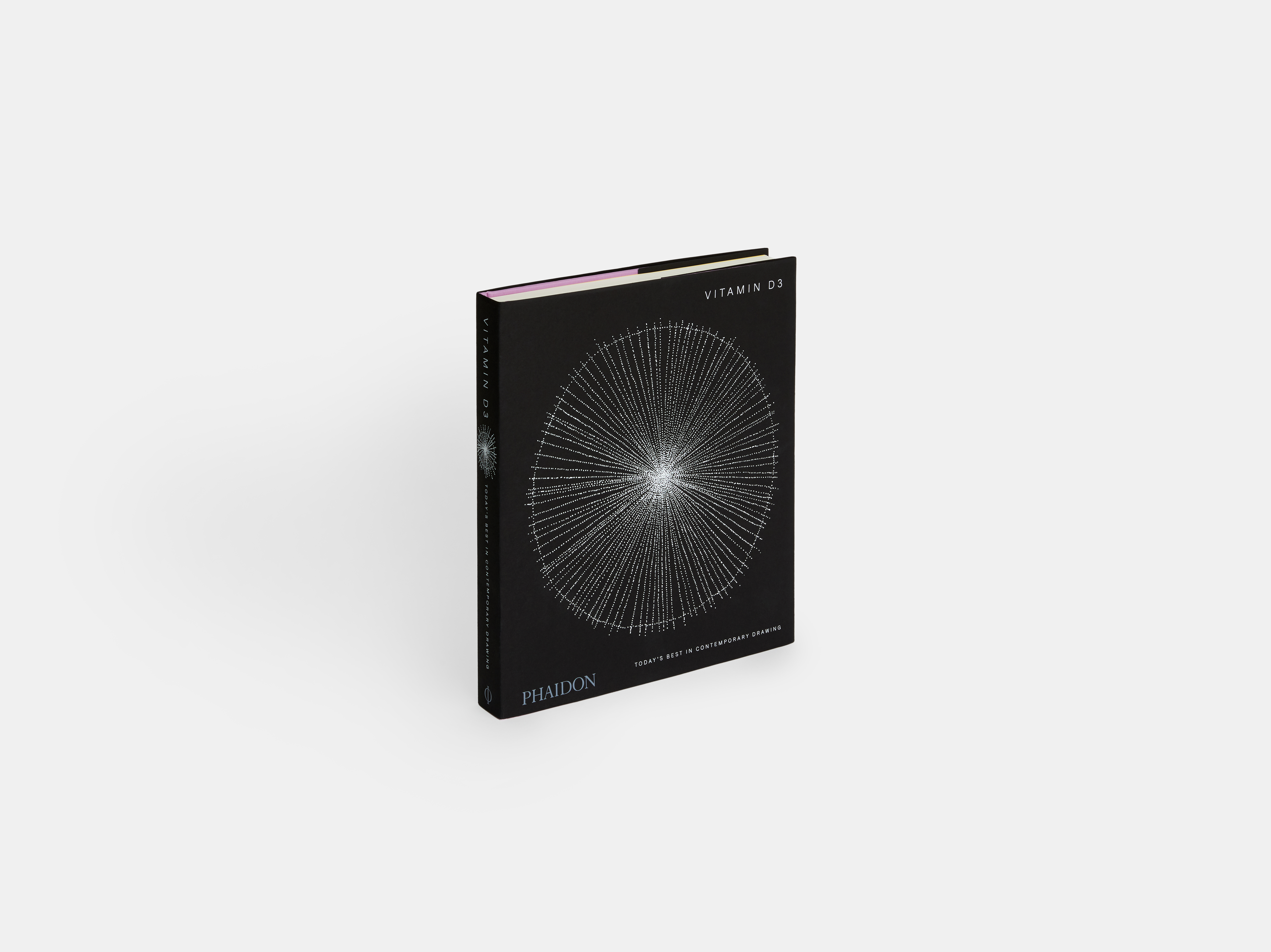

Quinn is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing , Phaidon's new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We sat him down and asked him a few questions about how, why and when he draws.

Big Rabbit, Little Rabbit

(2017) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Big Rabbit, Little Rabbit

(2017) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I am Nathaniel Mary Quinn, an artist, a husband, a human being — flawed and deeply insecure — and an extremely blessed and fortunate soul traveling on a path far removed from any given path I could have imagined for myself. Right now, my mind is consumed with my art practice; I have much work to do. Such conflicts with the repetitive phone calls from my wife as she deals with matters concerning the new house we recently purchased.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? My special relationship with drawing is that it sets me free; I feel powerful in the studio, akin to a God, being at the helm of all creation within the context of my time and space, having the final and only say-so on every single choice as embedded in producing my works. I describe my studio as a laboratory; I operate sort of like a surgeon or a scientist — which is largely wishful thinking, for I possess no real knowledge or understanding of a surgeon’s or scientist’s true activity and facility — but, in any case, the level of precision and accuracy are paramount in the development and creation of my works, in addition to the exploration of new ways of creating and solving problems.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? I imagine that there is an increased interest in drawing right now, a reassessment of sorts, especially considering the times in which we currently live — the Global Pandemic and its impact on the world and humanity — so, perhaps, drawing allows for immediate access to that which is fervently palpable and genuinely felt.

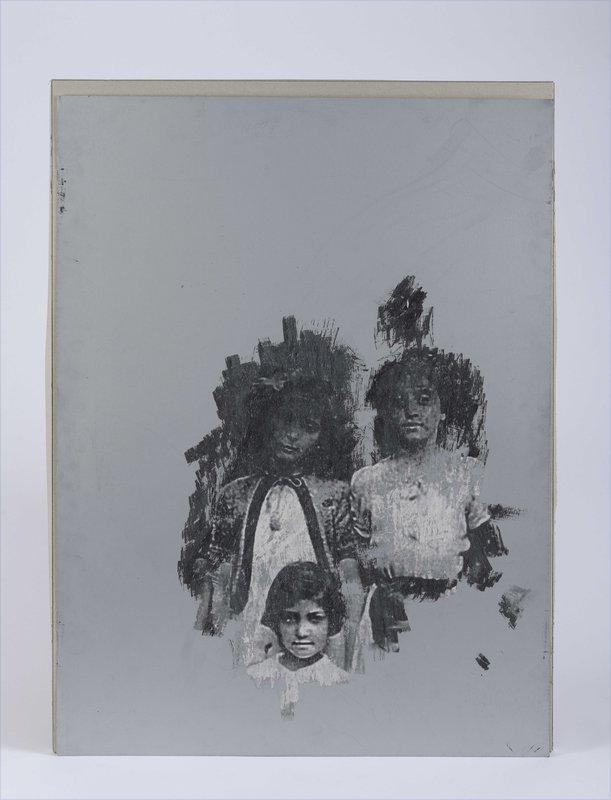

Charles

(2013) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Charles

(2013) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? The absolute most difficult thing for me to contend with is my deep sense of insecurity and severe lack of confidence in myself as an artist, as someone who pursues the activity of creating. I work incredibly hard on each work in order to overcome my fears of not being able to make a good work — at the very least, a decent work — yet, after the work’s completion, I never feel satisfied, I never feel happy about it. In fact, oftentimes, I feel like a failure. However, I most deeply enjoy the journey and process of making a work; yet, upon the journey’s end, marked by a finished piece, a most visceral and immediate response escapes my mouth and mind: “Quinn, you’re such a worthless coward; you’re so weighted with fear and insecurity! Stop being so fragile and weak. You must make better work! You must! How else do you expect to succeed? If you do not improve, you will fail!”

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Yes; the apparent immediacy and directness of drawing is much of the appeal for me, especially with dry materials — black charcoal, soft pastels, oil pastels — so everything is being captured in the moment, uninhibited by excessive thinking and over-intellectualization: there is no paralysis of analysis. In this way, I am able to follow how I feel, a more spiritual path, one that is not exactly tactile, an approach that’s a bit difficult to articulate — well, at least it is for me; I, no doubt, possess not the intellectual capacity to describe it — but, it’s an emotional experience that happens within a succession of moments, within the spiritual space of being present, where talent is aligned with work ethic, labour, and perseverance, where everything that seems to be understood or defined loses its structure and meaning, its belief systems and conditioning.

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something must of us cannot? Drawing as a child is the ultimate point of existence; it’s the kingship; there exists no form of liberation or freedom that can surpass it. Drawing as an adult is the constant battle to draw, again, like a child, for we are born kings and queens; we are born victorious. Yet, as we grow and mature, as we become adults in the world, we learn to become peasants, and this trap, this slippery and most efficient downward slope, will mandate or, perhaps more accurately speaking, guarantee one to draw like a peasant in bondage as opposed to the victorious king or queen one was meant to be — born to be.

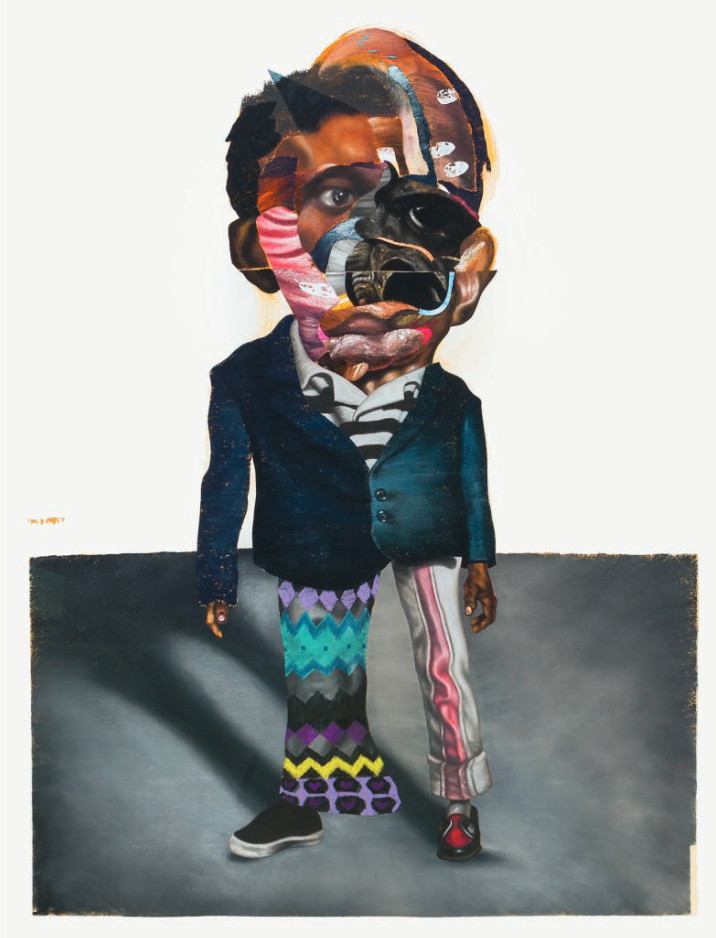

Old Man Slick

(2018) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

Old Man Slick

(2018) by Nathaniel Mary Quinn

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? It is my contention that what most people overlook when they think about drawing, when they attempt to assess drawing, is the severe lack of attention on the actual skill of drawing, of understanding its totality, of becoming close as possible to mastering such a skill. The mastery of the skill of drawing is incredibly important because it allows for the complete expression of the self: the more acutely sharp one’s skill, the more effective one will be in one’s unique expression. In this way, one will know how to “break the rules” without sacrificing the fervour and magical essence of one’s drawing. This, in turn, will embolden one to resurrect one’s unique visual language, a language that will be as unique as the person making the drawing. Michael Jordan worked so relentlessly and tirelessly on the mastery of the fundamentals of basketball that he acquired a profound grip on the skills of basketball, allowing him complete and untouched freedom on the basketball court, where he was able to operate in accordance to his desires, where the removal of limitations was achieved.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? I draw and paint every day. At times, perhaps after building a number of bodies of work for various solo gallery and museum exhibitions and works for art fairs, I may take a two-week break, which functions as a natural limit for me, for, at such time, life outside the studio becomes incredibly boring, and I begin to feel useless and lose any given extended interest in anything else. So, I return to the studio, the space in which I feel completely happy, powerful, and meaningful. I prefer working at home — my studio is in my house — so that my wife doesn’t have to worry about me being outside the home late into the night. I have to be completely alone while working; I much prefer being alone while working; I listen to podcasts while working; after taking a break to exercise, I return to working in the studio. I normally work from around 11:00am to 12:00am, everyday; on most nights, I work until 2:00am, which is very easy to do. Sometimes, I watch the news, documentaries, or movies while working in the studio, but it functions more as pleasant background noise. Podcasts and audiobooks are great because it feels as though the guests are in the studio with me, except that I do not have to respond to them. And it seems as though time races by while working in the studio; there is never enough time in the day. I find it quite displeasing and distressing when it is 3:00am and, by force of nature, accompanied with the knowledge of resting my body, I must end work in the studio in order to sleep. Yet, my adrenaline is pumping; I am so wired, excited, ambitious, hungry. During those late night hours, I find myself thinking: “Maybe this work will actually be good; maybe I will finally achieve my goal of making a strong work. But, if not, which is probably the case, then I’ll just make another work and try again.”

Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

You can see more of Quinn's work via his gallery Gagosian . Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing , featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, and Emma Talbot is available now at Phaidon.com . We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.