In 1995, a year after South Africa’s transition to non-racial democracy, Anton Kannemeyer published an autobiographical story in the fifth issue of Bitterkomix, an ongoing comic book he co-founded three years earlier. Titled ‘Boetie’ (‘Sonny’) and credited to Joe Dog, Kannemeyer’s occasional pen name, the cartoon strip opened with two panels depicting the artist – a frequent character in his work – bemoaning his inability to conjure fantasies in his drawings. Rendered in the spry clear-line style of Tintin creator, Georges ‘Hergé’ Remi, the ensuing tale recounted the sexual abuse meted out by the artist’s father, J. C. Kannemeyer, a renowned Afrikaans literary scholar. The story was an important template for the artist, suggesting a way to communicate difficult and traumatic subject matter plainly.

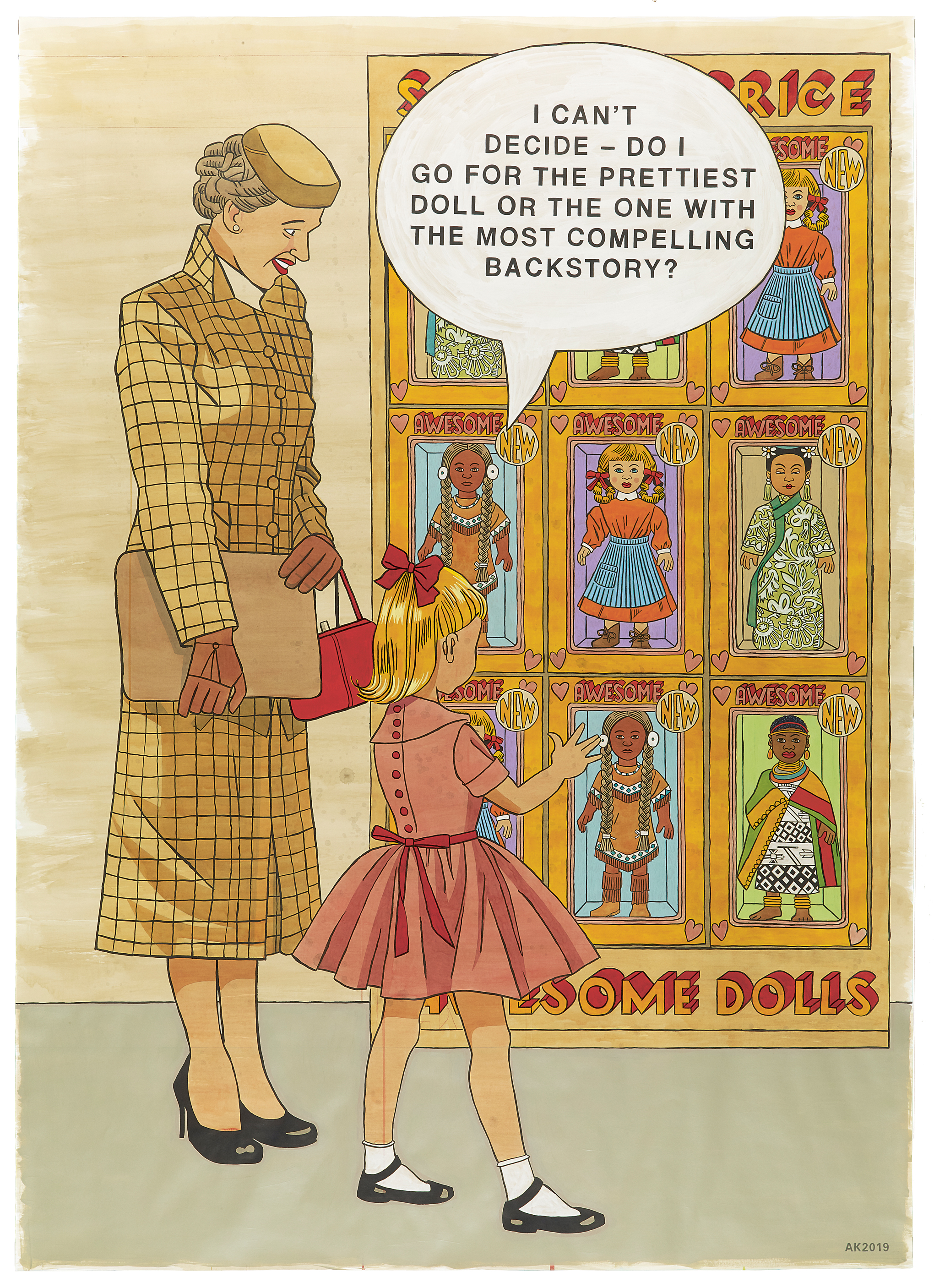

Kannemeyer’s sketchbooks, many of which have been exhibited in the past, track the evolution of his style from jagged and angry, to precise, analytic and elegiac. Kannemeyer’s anger – at his father, and the sham values his vanquished class once represented – hasn’t entirely dissipated and serves as the fulcrum for much of his practice. His output includes mocking satires of social manners. Initially aimed at religious conservatives, works like Compelling Backstory (2019) form part of a growing corpus skewering the mendacity and equivocation of liberals.

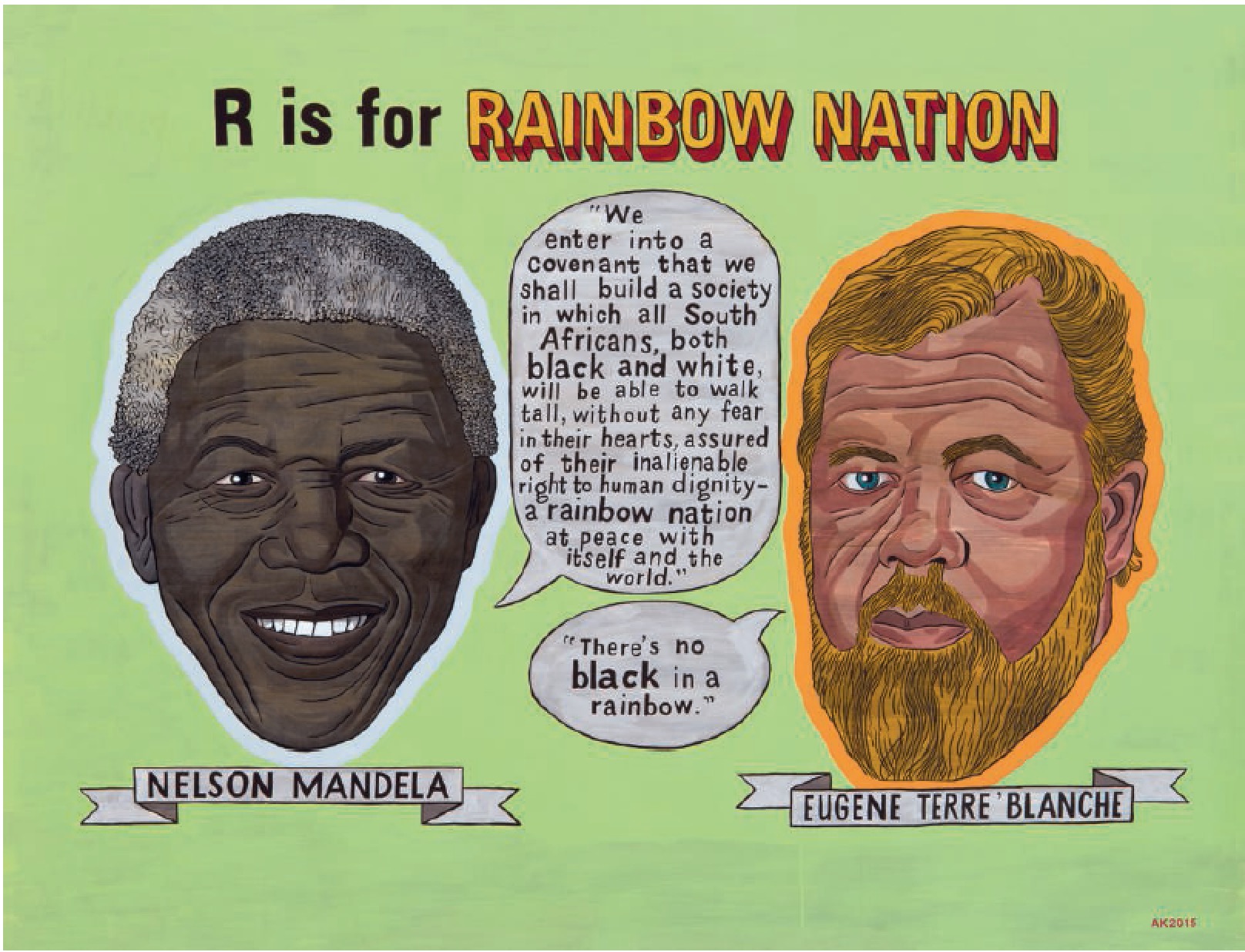

His ongoing ‘Alphabet of Democracy’ series is an epigrammatic archive of post-apartheid follies. Rendered in diverse styles, the series is linked by Kannemeyer’s fidelity to statement or event. Started in 2005, the earliest works in this series included a plaintive study of a dog lying next to a murdered farmer covered with a blue blanket (J is for Jack Russell). The series is now stocked with dancing ministers, crony capitalists, aspirant presidents and repentant sports cheats.

Kannemeyer is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing , Phaidon’s new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing featuring over 100 artists. We sat him down and asked him a few questions about how, why and when he draws.

Anton Kannemeyer, Compelling Backstory, 2019, acrylic on paper, 210 × 150 cm (82 ⅝ × 59 in). Picture credit: artwork (c) the artist / Photo: Jan Verboom

Anton Kannemeyer, Compelling Backstory, 2019, acrylic on paper, 210 × 150 cm (82 ⅝ × 59 in). Picture credit: artwork (c) the artist / Photo: Jan Verboom

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? My name is Anton Kannemeyer and I sometimes work under the pseudonym Joe Dog (especially when drawing comics). I’m currently working on an exhibition for the French Belgian gallery that represents me in Paris . At the moment I’m rather pre-occupied with the notion that offensive art is considered unacceptable or even criminal by the art community (and here I’m thinking of museum directors, gallery owners, curators, etc). The opposite implies that art should conform to a narrow set of rules which are considered morally correct at this moment. Any resistance to that notion can lead to an artist being cancelled or excluded from exhibitions and publications. This basically means that art that complies is considered “good” and art that offends is considered “bad”. I believe that it’s not a crime to be offensive, but that it’s every artist’s duty.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? Drawing is my practise. I also do large paintings, but the drawings are really my focus. I am a satirist and drawing is the way that I express my messages, whether they are on a wall, paper or canvas. I also draw in sketchbooks and in my journals: and I’m very interested in the combination of text and images. Not just visually, but more important conceptually. I’m also not obsessed by style: my drawings are in service of the message that I want to bring across. I often employ parody and that implies that I look at the original source in more depth, and stylistically my work will be influenced.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? I think it has for a while now. Certainly books like these support the idea. But I’m no specialist.

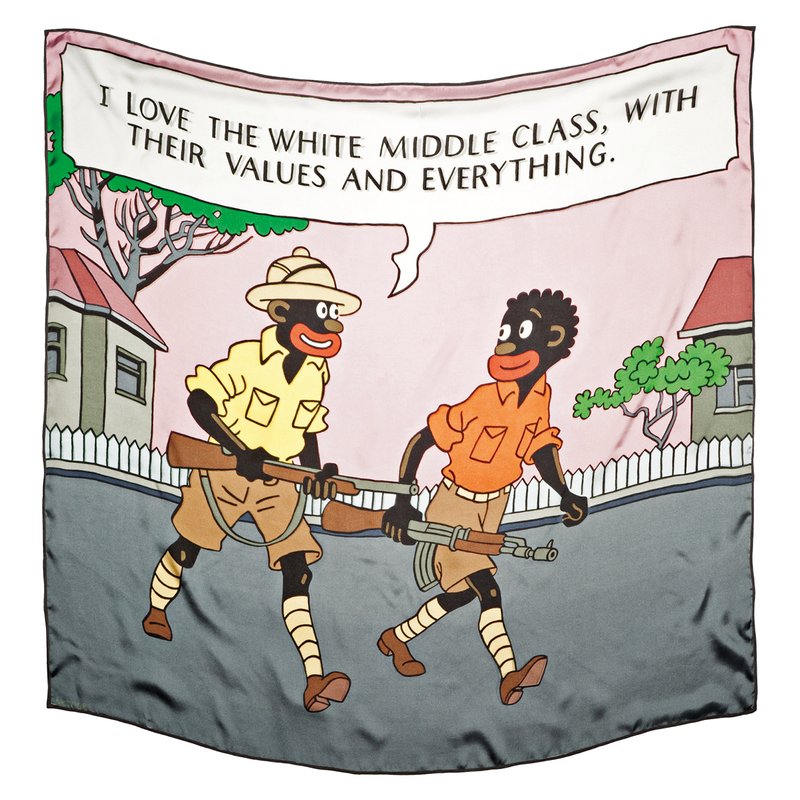

Anton Kannemeyer - R is for Rainbow Nation from the series ‘Alphabet of Democracy’, 2015, black ink and acrylic on paper

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? Drawing is about visual communication and the hardest thing to get right is to convey your message as clearly and as uncomplicated as possible. But it shouldn’t be so stripped that it becomes visually uninteresting. I often study editorial cartoons and some are simply brilliant in their economy, but often they are visually limited. To me it’s a struggle to get the balance right.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Certainly. I appreciate a quick sketch as much as a detailed drawing that took hours/days. I love the two classic opposites: Delacroix and Ingres. Neither one is always interesting, you absolutely need both. The artist who focuses only on quick sketches is probably the painter or sculptor, the other serves drawing as an art form in its own right. A quick sketch can capture all the essential characteristics of your subject, but a detailed drawing, and here I’m thinking of masters such as Dürer or Rembrandt (especially his etchings), is an end product (not that I support the notion of art as a commodity, mind you, I’m calling it an end product because it is complete - and probably made to exhibit).

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something must of us cannot? Here is an interesting anecdote for the young aspiring artist: When I grew up I was told by everyone that I’m not the artist, my brother was considered the artistic one. At high school I wanted to do art, but my father forbade me, so I ended up doing Maths, Economics and Accountancy. By that time I still loved comics and art, but gave up drawing, believing I was no good at it. I cannot remember drawing as a child and do not have any proof today that I ever did. But at 18 years of age I was so driven to be a comic artist (without being able to draw), that I eventually studied Graphic Design, the only course that included Illustration in South Africa.

When I eventually started drawing classes, I relied on stylistic devices (from studying certain illustrators and artists) and not on observation. But after a willingness to learn to observe (this is important for students to understand) I finally made a breakthrough in my second year of study. The only analogy that springs to mind is that it’s like learning a new language, one day everything still sounds like gibberish, the next day you understand and can communicate. It’s like walking through a dark tunnel and next thing the light appears. And this experience made me realize that anyone can draw, it really is just a language which you need to learn. Of course some people will draw better than others, but it really is something everyone can learn to do. This insight helped me tremendously when I was a drawing lecturer later in life.

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? I’m not sure that I quite understand the question here. But I do think that there are trends in drawing that make certain artists or drawings popular, but does not necessarily mean they are good. I’m rather critical of style, because it runs hand in hand with fashion. I’m interested in content and that should be the determining factor for a critical audience. That does not mean, however, that I dismiss the drawings of, say, David Hockney or Lucien Freud. Their drawings are searching and often brilliant.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? I work easiest early in the morning, and would often work out difficult solutions during this time. Not all drawing is the same; sometimes you just observe (as I do with my travelling sketchbooks) or you are executing a large piece which could take days or even weeks. I work best in solitude in my studio, but I can work with other artists as well. As a part time comic artist I’m sometimes required to draw in front of an audience, and this is something I really dislike. I am not an actor and I do not perform well in front of audiences, although lecturing is not a problem for me.

Phaidon's Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

Phaidon's Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

You can see more of Anton Kannemeyer's work at Huberty & Breyne Gallery in Paris/Brussels: Galerie Ernst Hilger in Vienna: Jack Shainman in New York: And, of course, on Artspace here. Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing , featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Emma Talbot is available now at Phaidon.com We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.