John Wood and Paul Harrison ’s drawing practice is also an essential part of their process when working in other media, especially performance and video. It facilitates a visual conversation about ideas, during which they might communicate their thoughts by sketching over each other’s drawings. The studio workshop is Wood and Harrison’s primary forum, whether for the construction of sets for videos, rehearsing performances or drawing, which is a quick and efficient method for setting out the overall structure of a work.

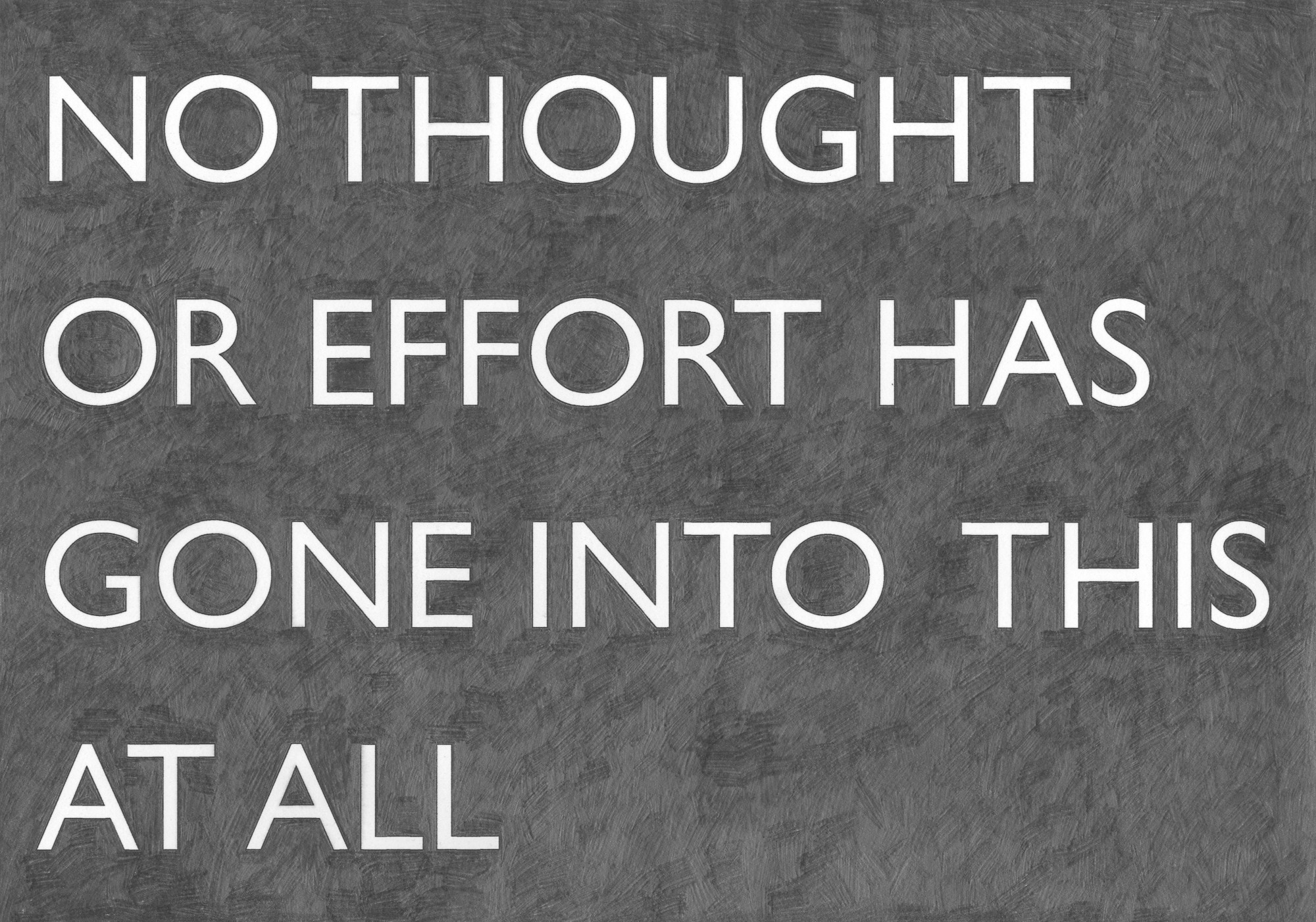

Wood and Harrison’s work is the product of two dry wits influenced by the history of slapstick performance and cinema. It revels in the absurdity of everyday life and routinely deflates the stereotypical overblown ego of the artist, as in their self-referential drawing No Thought or Effort (2013), which claims that ‘no thought or effort has gone into this at all’, a statement that patently contradicts itself. The apparent simplicity of Wood and Harrison’s work belies a philosophical finesse and conceptual mischief. Their deadpan humour often pushes at the limits of logic, exposing the treachery of language. At first glance, their drawing Red / Green / Blue (2013) seems banal to the point of tautology. Yet the joke is on the mind, as the punchline only lands once cognitive faculty has caught up with the visual sense, to realize that the words and colors are mismatched.

Wood and Harrison are among over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, Phaidon's new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We asked them a few questions about how, why and when they draw.

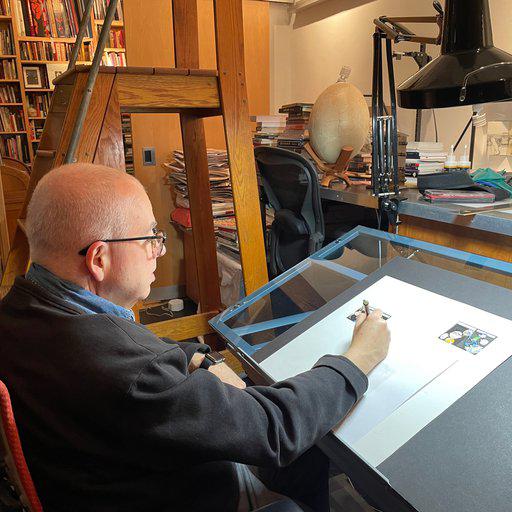

John Wood and Paul Harrison's studio - photo Stuart Whipps

John Wood and Paul Harrison's studio - photo Stuart Whipps

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? We’re in two minds about what’s on our mind right now. We are a two. We have two of things. We have two heads with two minds inside. One each. It’s not one mega mind. Far from it. In fact, increasingly as we get older, it feels like we just have one and a half minds. Between us. What is going on inside John’s 0.75 mind? After 30 years of working together I’d like to think I know. Sometimes I know, I think, and other times it’s like looking into the eyes of a small puppy, albeit a balding, roughly human shaped one, and I’m clueless. Is he coming up with a really nice idea or does he want to go for a walk? Being clueless can be a good thing, it can be kind of exciting. We can all be clueless on our own, of course, and we are no exception. But we also have a collective cluelessness. Being clueless can be a bad thing, it can be kind of frustrating. Drawing is one way we give ourselves and each other a clue. When we have something on our mind, we draw it out and we draw it out. Partly just so we don’t forget it. Drawing is a kind of mind ROM, a bit of extra, external storage. And we need it. We get forgetful, we forget things, like answering questions. We are John and Paul.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? Everything is a drawing, kind of. ‘Everything’ is a drawing, definitely. ‘Everything’ is a drawing in the shape of ‘Everything’, it’s just that we read it as a series of letters rather than see it as a series of shapes. Everything is a kind of drawing. We move an arm, drive a car, smoke a cigarette. You can draw with anything on anything or anything on nothing. We make thousands of drawings a day, you do too. Billions of us make billions and billions of drawings a day. It’s hard to have a special relationship with something that is everything.

But a lot of our drawings, when we consciously draw, you know like, ‘Hey, look at me, I’m drawing, on a piece of paper and everything’, do have a special relationship with the bin. We have a lot of ideas. Ideas for videos, paintings, sculptures and bits and pieces that we want to make and so we make a drawing of the idea. We do this for drawings too, we make a drawing of the idea of the drawing we want to make. Some of these ideas are very good (we think) some of these ideas are very not (we know). We have several tree’s worth of terrible ideas every year. We recycle of course, the paper and the ideas. And some of those terrible ideas can turn into not so terrible ideas, after we have made another drawing.

Most of these drawings never leave the studio. Some of these drawings do leave the studio. The ones that do leave have often been transformed into something else, a video, a sculpture, a text, a painting, which are still drawings really, it’s just that we call them something else, so people don’t get confused. Occasionally a drawing-drawing leaves the studio, something that most people would say is a drawing. ‘Oh, that’s a drawing’ they would say. Some of them might say, ‘Oh that’s a drawing, it’s not a very good one, but it is a drawing’. If we overhear one of these people, we make a drawing of them, and we laugh at it.

No Thought or Effort

, 2013, John Wood and Paul Harrison

No Thought or Effort

, 2013, John Wood and Paul Harrison

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? We made our first video work ‘Crossover’ in 1993. It’s me and John moving about, around, under and over a table and two chairs. Recently we have been thinking about remaking it, but without hair. We still have the original table we used, which we stole from a public school where we were resident artists. It’s the only art crime we have ever committed, apart from a work we made in 1994 called ‘Study number one’. Unfortunately, the table is the only bit we still have. We don’t have the original set, chairs, clothes or the ability to move about, around, under and over anymore. Well at least not within the original’s duration of one minute. We’d need a tea break.

One good thing about getting older though, which more than balances out one’s lack of ability to balance anymore, is that you gain a kind of perspective on things. It’s not any kind of wisdom really, it’s just about being about, for quite a while. And while you are about you notice that things come and go and come back again. ‘Painting is dead!’. ‘Painting is back!’. ‘Painting’s only gone and died again!’. ‘Nothing much is going on this week… Painting!’

More than this though, more than the seeing of the coming and the going, is that you see that things never really come, or in fact go. They are just there. Somewhere. All of the time. Back in 1993, when we made ‘Crossover’, the Art World felt more like a small village or perhaps, more accurately, a gated community. It wasn’t better or worse, there was just less of it. Now there is a lot of it. And because there is so much of it, a confusing amount of it, it’s tempting to try and see some order in it. The ‘This is important right now!’ show, the ‘If you are not doing this you are irrelevant’ book, the ‘If you are not thinking about this, be very, very ashamed’ article. But the disorder of it, is the fun bit of it. As an artist, uncertainty is the only certainty. Every day, everything is reassessed.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? If you have seen any of our video works, the ones in which we appear and perform, it will probably come as no surprise to you that, at school, we were ranked below average in sport. It should also come as no surprise that we were ranked above average in art. We hope.

But we weren’t any good at art at school. What we were above average at was copying. We could look at something and make a roughly recognisable copy of it on a piece of paper. ‘Sir, sir, John is copying from the book!’ resulted in a ticking off. ‘Sir, sir, John is copying that bowl of fruit!’ resulted in a tick.

Like the dislike of people who grass you up, the liking of liking praise for being technically good at art is difficult to let go of. I still like it when John lets me stay in at playtime if I’m doing a good picture, especially if it’s wet playtime. But being technically good isn’t always technically that interesting. Sometimes it is but sometimes something a bit wrong can be really right. The most difficult thing to continually get ‘right’ is to remember, continually, that you decide what ‘right’ is.

John Wood and Paul Harrison,

Red / Green / Blue,

2013

John Wood and Paul Harrison,

Red / Green / Blue,

2013

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? We have three main faults. The first is underestimating how many faults we have. The second is watching too much TV. The third is making up annoying catchphrases. We have a lot. They are often stupid and stupidly unfunny, but they act as a kind of code or shorthand for a shared experience we want to reference.

‘Break even, cover our costs, that’s our business model!’ is one of them. It’s one that acknowledges both how terrible we are at business and also how, sadly, we would never had made it onto ‘The Apprentice’. We did warn you about our second fault. ‘Nothing’s ever easy’ is another. We use this one a lot. The classic definition of insanity applies here. We have an idea and no matter what it is, how complex or simple that idea is we always underestimate what it will take to get that idea out of our heads and put it into the world. The apparent immediacy or directness of drawing does appeal. It’s just that quite often it is neither.

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something most of us cannot. At school we were often told we could only do our picture after we had finished our story. I’m sure some of you were too. Writing was the hard bit and drawing was the reward. Imagine then, a career where you just get to do the fun, rewardy bit. That is what being an artist is. But of course, it’s not. Because the fun bit becomes the hard bit and anyway you still have to do the hard bit too. You still have to do the writing. It’s just that they take the form of accounts, answering emails, answering interview questions…

‘Everyone is a dentist’ is quite a terrifying idea. Almost as terrifying as ‘Everyone is an artist’. Imagine if everyone was an artist. Absolutely nothing would get done. Things would fall apart. Albeit perhaps in an aesthetically pleasing way. Everyone is creative or has the potential to be. Everyone could be an artist. It’s just a good job for everyone, especially artists, that they don’t want to be. It’s a good job. Being an artist. Not a proper one though. But it’s a job. And that’s the difference.

Drawing as a child should be fun, if not, you are doing something wrong. Or more accurately someone else is not doing their job. Drawing as an artist should not be all fun. If it is, you are doing something wrong. You’re not doing your job.

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? Most people can overlook the fact that most artists can overlook. ‘Yeah, but when is a work really finished?’ said most art students, at one time or another. It’s a classic art school cliché. There are lots of them, clichés I mean, art students too, there are also lots of those. Art students are brilliant and it's brilliant being an art student. It’s a difficult subject to study though, fantastically confusing, there isn’t a guidebook and it’s impossible to be taught art really. So, at points when you, as a student, are fantastically confused, you can find yourself talking crap.I did it, John certainly did. Everyone does.

‘I don’t really mind how people interpret the work, it’s completely open to er… interpretation’. I interpret you as being lazy.‘I’m doing lots of research’. Googling does not count. ‘My work is about process’. Everything is a process. Writing this sentence is a process. ‘Yeah, but when is a work really finished?’. That’s an interesting one. It’s interesting because even though it’s often used only as a clever-clever response it really speaks of the difference between being an art student and being an artist.

Making art is really just about making decisions. A lot of decisions. And not just the what and the how but also the why. And you have to make those decisions and those decisions have to be final because you have to finish making the art because you have to show it. And sometimes, for all sorts of reasons, those final decisions are not the right ones.

Politicians really should go to art school. Because one of the most important things you learn there is that you will make mistakes, you will be wrong, you will be wrong an awful lot of the time. And you learn that this is an essential thing, a natural thing, a wonderful thing. So, you might as well own up and own the mistake. So, when people look at a drawing and they try to assess it, it’s important not to overlook the fact that what they are looking at could be a mistake. Something could have been overlooked. A final decision gone wrong. And that mistake, that wrong, can be kind of a beautiful thing. But maybe that’s just another art school cliché.

John Wood and Paul Harrison

John Wood and Paul Harrison

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? We had a conversation the other day in the studio about which one of us annoys our non-artist partners the most. After much carefully considered debate and a bit of a squabble we agreed that it was probably a draw. We are both annoying, we couldn’t live with ourselves, if ourselves were our non-artist partners. And it’s mainly because we are a bit immature.

To be fair though, it is part of the job spec. Artist wanted. Must be able to make art. Must have not properly grown up. It’s hard to maintain a sort of childlike wonder about the possibilities of things if you are no longer a bit of a child. But if there was a period when we began to mature as artists rather than as humans then it was probably between the mid 90s and the mid 2000s. During this period, it seemed to us anyway, the idea that anyone could be a ‘genius’ was frowned upon. The job of being an artist was not a special job, just a different job. Like being an electrician was a different job to being a baker.

We did and we still do like this lack of difference and distance between making art being your job and making bread being your job. Maybe the events of 2008 made people panic. Made the art market, like many other markets, panic. If artists aren’t really that special, different, better than the rest of us, why would people pay so much for what they do? And so maybe that’s why the idea of the genius has slowly crept back into common usage.

‘Sorry, no bread today, wasn’t quite feeling it’ said the sign on the door of the soon to be permanently closed bakery. I’m sure that bakers have good days and bad days. Days when they are loving the bread and other days when they can’t be arsed. It’s the same with artists. The idea that we should get special dispensation because what we do is make art, is kind of alien to us. Our job is to try and make art. It’s what we try to do every day. Even if, as is sometimes the case, we’re not quite physically, spiritually or mentally arsed. Of course, it helps if you are geographically close to the materials you are using, that’s handy. Unless you have really long arms.

Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing

You can see more of John Wood and Paul Harrison’s work on their instagram @woodandharrison. Meanwhile, Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing featuring over 100 artists including: Tania Kovats, Rashid Johnson, Rebecca Salter, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Deanna Petherbridge, Christina Quarles, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Emma Talbot is available now . We'll be running more interviews with artists featured in the book in the coming weeks.