Many artists teach to support their art careers, but Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook has made an art career of teaching. Rasdjarmrearnsook, a longtime professor at Chiang Mai University in her native Thailand, is known for conducting earnest, seminar-style discussions with particularly unpromising participants: stray dogs, cadavers, and patients at a mental hospital, to name a few. Buddhist monks and giggling schoolchildren also figure in her first U.S. retrospective (at SculptureCenter through March 30), which follows appearances at major festivals such as dOCUMENTA 13 and the 2005 Venice Biennale. She spoke to Artspace deputy editor Karen Rosenberg about spirituality, Thai culture, and the niceties of teaching the living and the dead.

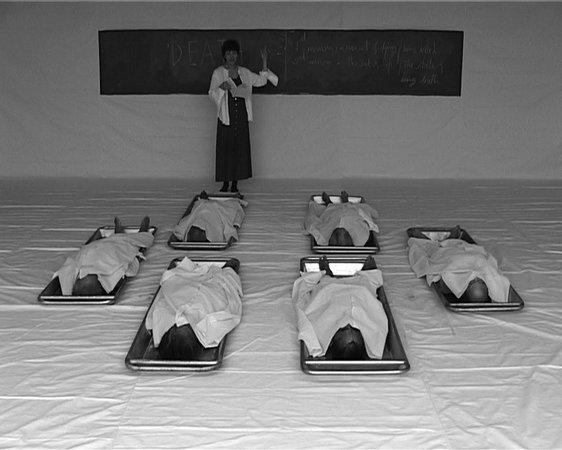

In your video series “The Class,” you lecture bodies in a hospital morgue. Where did that idea come from?

In 1996 I got a grant from the Asian Cultural Council to come to New York for a few months. It was my first experience working in a living space, and I began to use materials from daily living—a teacup, mattress, pillow. When I went back to Chiang Mai, I began to sculpt with clay and to live with the sculptures—one on my bed, one sitting and having breakfast with me in the kitchen, and one standing near my front door. The process of taking care of those clay sculptures was similar to preserving bodies, because I had to spray water on the clay and wrap the sculptures with wet cloth. I wrote a proposal for a big hospital in Chiang Mai, to allow me to work in the anatomy department.

How did the hospital react to this idea?

It’s strange—23 physicians interviewed me, and most of the young doctors said no. But most of the doctors over age 50 understood.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, The Class I, 2005. Video still. Courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

There’s a history of artists working with cadavers for anatomy lessons, going back to the Renaissance. Do you see yourself as part of that tradition? Or something more ritualistic, more spiritual?

In Thai culture we really believe in ghosts, or spirits. A doctor who interviewed me, a woman about 30, asked me how I knew that I could communicate with spirits. I don’t know whether I can communicate with spirits or not, but her question showed me that in Thai culture even an academic person, a young doctor, still thinks that way.

There’s also an element of ironic pedagogy—you’re lecturing the dead about death.

Thai people have a saying, that you teach something to a person who knows about it better than you.

Some of your recent works use the format of the art-history lecture, often with a cross-cultural twist. You have filmed Thai villagers looking at reproductions of Manets and van Goghs, or monks drawing moral lessons from Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman.

The image should not be too clever—it should concern people’s lives, and allow them to improvise. A monk said of the Koons [juxtaposed with a depiction of Judith and Holofernes]: “That man has two wives—that’s why he was killed!” I think these works of mine were interpreted as being against art history. Villagers talk about Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass and make dirty jokes.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Village and Elsewhere: Jeff Koons' Untitled, Cindy Sherman's Untitled, and Thai Villagers, 2011. Digital pigment print. 28 x 37 1/4 in. (71 x 96 cm.) Edition of 9. Courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

When you are conducting discussions with someone who can’t talk back, how do you fill in the other side of the conversation?

I have dogs, and if you live with animals you always speak a question and an answer because they can’t answer you. You have to guess. It’s the same situation as in a class, in university. I often speak alone. When the work was shown in the Venice Biennale, in the Thai Pavilion in 2005, some curators and critics said, “You talk like you’re speaking to viewers but you’re actually speaking to yourself.” I thought that was an interesting reaction.

How do you deal with the ethical issues of working with the dead?

The first priority was finding the dead without relatives. I gave the videos to the hospital when I was finished. I also worked with doctors, who came to watch and had specific conditions for how many hours I could work. But I got a negative reaction from academic art circles in Thailand. They referred to morality or ethics, more than thinking about art creation. That disturbed me.

You also made a piece where you’re performing a kind of funeral rite, covering a single body—the body of a young woman—with a series of dresses. What prompted that response?

I was in the hospital working on another piece, and I saw a woman whose body had arrived during the night. Normally in a funeral they will dress the body very beautifully, in a suit, but this woman had on only a t-shirt and sport pants. I thought her body had not been in a Thai funeral, so it would be good to dress her. I was thinking about gender, about relationships between women. In Thai art circles there are not so many women—not many female students, and especially professors.

You’ve also filmed women in mental institutions. This time you’re not teaching, just letting them talk.

I went there because I was not sure if I was normal or insane! When your work is so non-traditional, the reaction from the people around you implies that you are not normal. A nurse who worked there said it’s a very thin line between a person in the hospital and one outside.

You do a lot of work with stray dogs, often dogs you’ve rescued. You're clearly an animal lover, but what makes them appealing as art subjects? How do they relate to your other subjects?

It’s about the relationship between humans and another species. We give humans too much value; we see ourselves too clearly. We never see another species that needs help from us. That’s why I decided to travel with a dog to dOCUMENTA. We stayed in a small house in a park in Kassel, and asked for donations to help other stray dogs in Thailand.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Pray, bless us with rice and curry our great moon, 2012. Video still. Courtesy the artist and Tyler Rollins Fine Art.

In Thailand there’s a special relationship between dogs and Buddhist monks, who take them in and feed them.

People take their dogs to the temple and leave them there. People don’t realize monks have no money. It's a place where, you think, life can survive.