Adam Pendleton is a young contemporary artist, but one who is fully engaged with the past. As the Whitney Museum of American Art curator Adrienne Edwards puts it: “Pendleton’s art is an acknowledgement of, and a response to history, understood as a series of patterns and structures through which it manifests and makes itself known."

Although his work often engages with racial politics, Pendleton says the monochrome he uses in his palette is “not connected to race.” Instead he is more drawn to the chaotic nature of the paint on canvas. “I love that I can’t always control how much paint comes out, so I end up with these drips and splatters, these beautiful mistakes,” he says. “These errors are what make the image worth looking at.”

Today, Artspace is proud to announce the release of a very limited edition Pendleton silk screen,

Untitled (Mask), 2020

printed on 410 gsm Lascaux Carbon Blank Radiant White paper 11.00 x 9.50 in (27.9 x 24.1 cm), signed and numbered in an edition of 50, accompanied by a signed Phaidon hardback book.

Untitled (Mask), 2020

features a photocopied image of a mask from the Dan people of Liberia. Translated onto a clear substrate and layered with repetitive markings, the mask, several times removed from its source, hovers between transparency and opacity.

For Pendleton, masks provide a very different way of thinking about forms, or images, that are driven towards, or driven by, a kind of distraction, and driven by the impulse to transform, to transfigure, to become something else.

"I use these Dan masks, and what I think the masks do is distract,” he has said. “They transform, they create a vibrational space and a distance, in relation to a certain performance of identity, in relation to a performance of self."

Born in 1984 in Richmond, Virginia, Pendleton graduated from high school two years early, and studied in Italy before moving to New York at the age of eighteen, intent on becoming an artist. Succeeding remarkably quickly, he gained a reputation for visually arresting works, often filled with words that weren’t easily reconciled.

His best-known series of works, Black Dada, began in 2008 as a text which drew on 20th century avant-garde sources, as well as more recent material, to “problematize the relationship between conceptual art and civil rights, or the avant-garde and black history,” as he has described it.

Black Dada is often referred to as a manifesto - Pendleton doesn't refute the title - but it’s also poem-like in its construction and strong formal structure. It samples several historical manifestos and poetic texts and is, in essence, a kind of declaration of how he wants to function as an artist. This masking of either text or image is a consistent thrust behind a lot of the visual projects that he takes on: a filtering or masking of familiar or basic elements.

He is currently represented by PACE in New York, London, and Hong Kong; David Kordansky in Los Angeles; Max Hetzler in Berlin; Pedro Cera in Lisbon; and Eva Presenhuber in Zurich. His September 2021 exhibition (running through January 2022) at MoMA, Who is Queen, responds in part to the Occupy and Black Lives Matter movements

In 2017 Pendleton, alongside fellow artists Rashid Johnson, Ellen Gallagher and Julie Mehretu, pooled their resources to buy the childhood home of the singer-songwriter Nina Simone, in Tryon, North Carolina. As Pendleton told the New York Times, “It took me about five seconds to know what I wanted to do.” The quartet paid $95,000 for the three-room, 660-square foot clapboard house where Simone was raised, after an earlier rescue attempt failed and the building was in danger of falling into disrepair. We caught up with Pendleton and asked him a few questions about his practice and the new edition .

ADAM PENDLETON - Untitled (Mask), 2020

What does this image mean to you and what should people look for in it? For me the mask is a transformative object that facilitates becoming. Not necessarily becoming anything in particular, but becoming in the abstract, removed from the relationship between states of being or states of identity, even prior to those states, exterior to them and not derived from them. A process that describes no determinate inputs or outputs, starting points or endpoints. That’s reflected in this work, which is itself an index of becomings (or transformations, or translations). Of course, the mask that I am borrowing does something very different in its own cultural context, but at least shares this capacity for transformation.

You often work in series, can you suggest how a buyer of contemporary prints and silkscreens should hang this new edition? This work has an immediate effect. Its stark black-and-white character is definitely one of the first things that people notice about it. But it also withholds. It involves an image of a mask, and that is part of a mask’s function: to withhold, or to withdraw. And so, it’s sort of difficult, uncanny, and I am tempted to say haunting. It does not recede, but it also does not give itself over to you completely. Its presence likely takes up more space than you would imagine, in spite of its modest scale.

We understand you get up at around five each morning to read, often photocopying passages of text to reference in your work. What's in your reading pile at the moment? Recently, I have been reading Figure It Out , Wayne Koestenbaum’s newest collection of pointillistic essays; Isabelle Graw’s The Love of Painting , which traces the quite vibrant life of contemporary painting even after its 'death'; and Joan Retallack’s latest project Bosch’d , after Hieronymus Bosch. Like Bosch, who painstakingly observed both the joy and grotesqueness of human and non-human life, Joan’s poetry pushes reason beyond its limits. I’ve been an admirer of her work for years.

Your forthcoming exhibition at MoMA, Who is Queen, responds in part to the Occupy and Black Lives Matter movements. What is your thinking behind placing those two movements together and can you tell us about the wide array of people you chose to voice the show? Who Is Queen? is a large-scale multimedia exhibition that fills the height of MoMA’s atrium. Three towers made of wooden scaffolding act as armatures for various works, including paintings, works on Mylar, sculptures, and a continuously modified sound collage that combines archival and newly commissioned audio. My most recent series of paintings will be featured.

Occupy and Black Lives Matter are two significant social movements to have emerged in the United States in the past decade. Among other things, they prompt us to re-evaluate the fabric of America: to pose the question—and not for the first time—of what kinds of collectivity and what kinds of life are possible in this country. This involves both utopian and dystopian thinking, and a reckoning with historical possibility. What makes these movements different from historical upheavals, both in terms of politics and aesthetics? How do they—perhaps unexpectedly—align? I suppose I am, as an artist, most interested in the formal problems that the discourses around such protests introduce. I am bringing them into a space of abstraction, and part of what this project is about is the tension created in that translation.

I think of the We Are Not paintings, which layer the spray-painted titular phrase, “WE ARE NOT,” as pertinent here. As this phrase struggles to enunciate or even seems to refuse a collective subjecthood—“WE”—this struggle is itself constitutive of subjectivities-in-process: a chorus of voices.

Obviously Black Dada has defined your work to date. But do you see it as something with a finite timeline? Or do you have strong sense of how it will evolve? Is it maybe something like Sol LeWitt’s Paragraphs of Conceptual Art – the guiding light to everything that will come? Black Dada is continuously revising itself; its unfolding isn’t prefigured in any of its given states, despite a certain appearance of systematicity. It’s designed to be generous, to accumulate diverse materials and positions, and to drive the notion of a system beyond the point at which any completeness breaks down. Part of its value for me is the refusal of trajectory and the capacity to surprise, and so I hope it remains that way.

You’ve said that Black Dada is a way for you to talk about the future of the past. What elements of the past do you think might be the touch points of our future for contemporary artists? “Black Dada is a way to talk about the future while talking about the past.” I am not sure it’s as much about digging into the past and instrumentalizing the material that lies dormant or forgotten there (although this is certainly important, as well as something that can be done both well and poorly). There is rather an ambiguity to the parallelism that the sentence constructs, and a more abstract standpoint involved in the activity of “talking about.” Speaking the future and the past at the same time, placing them in counterpoint. In general, I think it’s an ethos of experimentation and juxtaposition rather than finding particular points of reference for some kind of futurology. Some things work and some things don’t.

ADAM PENDLETON - Untitled (Mask), 2020

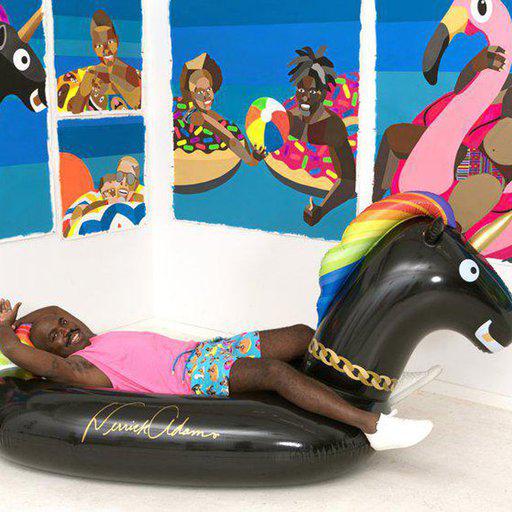

The signed and numbered Adam Pendleton silk screen (bottom right) with accompanying signed Phaidon book above

The signed and numbered Adam Pendleton silk screen (bottom right) with accompanying signed Phaidon book above

Are you aware of your attitude to the archival images and found footage you draw upon changing in your day-to-day work? Is there a fundamental change in how ‘history’ moves now, compared to say, when you were a kid growing up in Richmond? There is a constant interest in the still image, the institutional image, and the space of the book, as well as techniques of montage. Images move faster today than they did even ten or twenty years ago, and this movement likely no longer really follows the logic of montage or of the book. But I think the way images become incorporated into my work has not changed too much. I have always had an interest in overwriting, annotating, and creating networks of images, and I am tempted to say that at this level these are almost universal attitudes, in terms of the histories of visual and textual culture.

You’ve spoken in the past about the 'instructional' element of Robert Ryman’s paintings; are there contemporary artists you’ve seen who you feel a kinship with who are maybe mining a similar seam? Robert Ryman’s work was certainly an influence on the Black Dada paintings, an earlier series of mine that worked with radical subtraction. Lately, I’ve been more interested in the constructed space that is developed in the work of Norman Lewis and Jean Dubuffet. In my work, in the We Are Not paintings, I am trying to shift from an individual voice to a voice of the chorus, and so while looking to Lewis and Dubuffet I am finding ways to construct a space that corresponds with this polyphonic voice. I have been experimenting with scale, greatly expanding the space of the painting, which more than anything gathers more voices into its field. I want multiple, diverse realities, nonetheless conversant with one another, to exist within the work.

With a new president (and with it a new optimism) do you wonder whether some of the momentum for change at street level could actually decrease? I am not sure that the U.S. presidency is a major factor either way for these particular modes and territories of struggle (the street level). I would note that Occupy and Black Lives Matter—as well as some other notable activist events, like the pipeline protests at Standing Rock—were initiated during the Obama administration, whose politics the Biden-Harris administration seems poised to continue. So the precipitating conditions, as well as most of the state’s techniques of management, whether at the local or federal level, have remained largely consistent. But I think it is also true that these social movements can unfortunately be quite quickly demobilized and sapped of momentum, and we have seen that happen too.

What are you planning to do with the Nina Simone family house? (and did you got the recent vinyl reissues of Pastel Blues and I Put a Spell On You?) In the long term, plans for the use of the house are to-be-determined. As of September of this year, the house is permanently protected thanks to a preservation easement held by Preservation North Carolina, and secured in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The National Trust has also been working with local organizations in Tryon, NC, where the house is located, to chart a course forward. I am not much of an audiophile myself, in terms of vinyl collecting. But, of course, I love Nina Simone’s music, and it’s great to know that the reissues are being done right.

How has art helped you through what has been, for all of us, a difficult year? For me, my own artmaking has allowed me routine and focus in this time of mass disruption. It was also amazing to be able to return to museums after the recent period of closure—I didn’t realize how much I had missed them.

Untitled (Mask), 2020 printed on 410 gsm Lascaux Carbon Blank Radiant White paper 11.00 x 9.50 in (27.9 x 24.1 cm), signed and numbered in an edition of 50, accompanied by a signed hardback Phaidon book is available to buy now .