Few natural phenomena so preoccupy the human imagination as the Sun. Since prehistory, the Earth’s nearest star has been recognized as a precondition of our existence, providing us not only with light and heat, but also sustaining the crops on which we feed. It has been worshipped as a deity by cultures across the globe, and is central to every human society’s conceptualization and measurement of time. In an era in which we are finally beginning to recognize the suicidal madness of our reliance on fossil fuels, harnessing solar energy might be our species’ best hope of survival. But if the Sun proves to be humanity’s savior, this will be only a temporary stay of execution for terrestrial life. In 7.5 billion years’ time, it will enter its red giant phase, and incinerate the Earth.

It follows that artists throughout history have confronted the subject of this celestial body. Turner proclaimed simply that ‘The Sun is God’, while Whistler complained of ‘the unlimited admiration, daily produced, by a very foolish sunset’. Here, we gather together six works from the Artspace store that focus on all things solar. The Sun, here, is presented as both a spiritual inspiration and a spur to reason, a power supply and a wellspring of kitsch, an ancient clock and the source of life itself. Ladies and gentlemen, here comes the Sun!

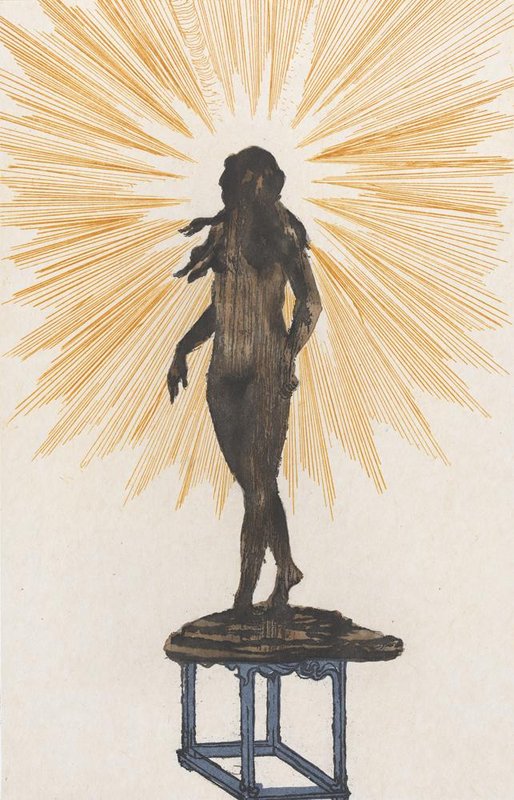

Mamma Andersson, Sundial (2013)

While the earliest sundials known to archaeology were produced by ancient Egyptian and Babylonian astronomers around 1500 BC, the principle of the solar clock has existed since ever since prehistoric Homo sapiens first noted how shadows lengthen as the day draws on. In Thomas Love Peacock’s famous early 19 th century poem The Sundial , this device is a reminder of our mortality, and ‘Seems / like the ghost of Time, to mock / The wrecks of power that once has been’, while in Hilaire Belloc’s verse On a Sundial (1938) it is proof that ‘Death and Life are one / There falls no shadow where there shines no sun’. Solar rays may be ultimately responsible for sparking us into existence, but they also mark the dwindling of our brief and soon-forgotten flame.

In the Swedish artist Karin ‘Mamma’ Andersson’s print Sundial , the titular device’s gnomon (or shadow-casting element) takes the form of a statue of a female figure, whose plump curves and tumbling tresses recall the voluptuous nymphs and Olympians painted by Sandro Botticelli. Silhouetted against a halo-like sunburst, she might be a solar deity, a rare womanly counterweight to the male sun gods that populate so many pantheons, from the Egyptian Ra to the Roman Sol Invictus, from the Aztec Tonatiuh to the Celtic Belenus. Notably, the artist (who represented Sweden in the 2003 Venice Biennale) does not fit her sundial with a clock face. If this seems strange, we should note than while humans measure out their days in minutes and hours, Andersson’s solar goddess is surely blessed – or burdened – with eternal life.

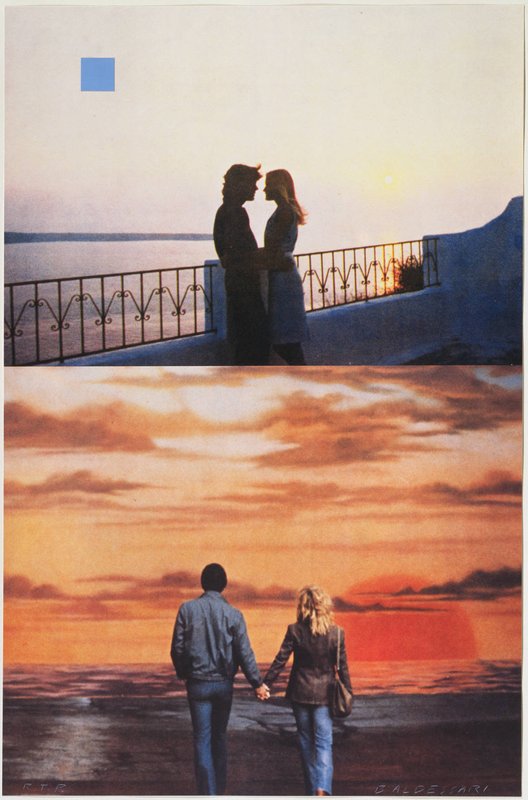

John Baldessari, Two Sunsets (One with Square Blue Moon) (1994)

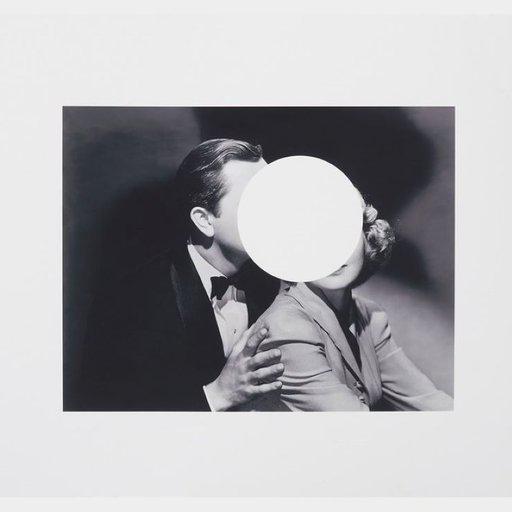

A pioneer of American Conceptual Art, John Baldessari made his name in the 1960s with a body of largely text-based paintings, featuring such ironic statements as ‘A TWO-DIMENSIONAL SURFACE WITHOUT ANY ARTICULATION IS A DEAD EXPERIENCE’. After burning many of these canvases and baking their ashes into cookies as part of his iconic – and iconoclastic – work The Cremation Project (1970), his attention turned to found imagery such as stock photographs and film stills, which he would juxtapose, combine with text, or partially obscure with adhesive dots to witty, destabilizing effect. As Baldessari put it: ‘What if you just give people what they want? People read magazines, and look at photos, not at Jackson Pollocks’. His was an art that belonged not to the rarified realm of the academy, but to the real, image-saturated world.

In the screenprint Two Sunsets (One with Square Blue Moon), Baldessari brings together two images of a pair of lovers, respectively kissing and holding hands while the Sun goes down over a bronzed and tranquil sea. So familiar is this scene from cheesy Hollywood movies and the dust jackets of kitsch romance novels that our initial response is an affectless shrug. It’s only when we note the disarming presence of the impossible, square blue moon in the upper image that we’re stirred from our visual torpor, and perhaps our cynicism. No matter how much they’ve been cheapened by pop culture, both love and sunsets remain things of profound beauty – everyday miracles. The same might be said of the moon, which few of us would exchange for Baldessari’s knowingly paltry squared-off orb.

Chiho Aoshima, Yuyake Chan Miss Sunset (2006)

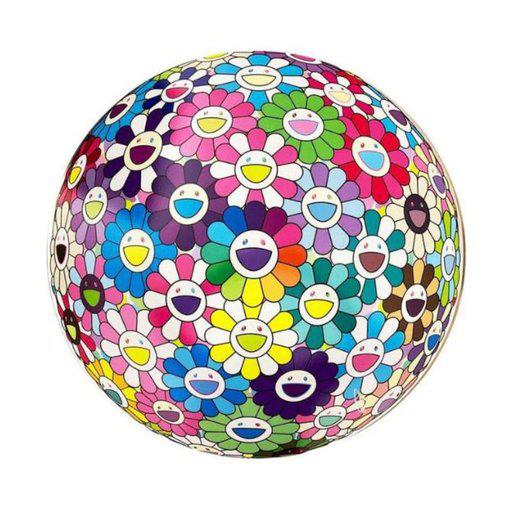

A protégé of Japan’s most celebrated contemporary artist, Takashi Murakami, Chiho Aoshima has described her work – which draws on both 19 th century ‘ukiyo-e’ masters such as Hokusai and 21 st century manga imagery – as ‘strands of my thoughts that have flown around the universe before coming back to materialize’. What preoccupies Aoshima is that ‘humankind and nature [are] two souls who cannot understand each other’, which accounts for both our species’ destruction of the natural world, and the sudden, retaliatory violence of earthquakes, tsunamis, and pandemics.

While at first glance her compositions cleave to the Japanese culture of kawaii , or cuteness, look closer and it becomes clear that they are products of a singular, often eschatological imagination.

The titular figure in Aoshima’s print Yuyake Chan Miss Sunset is part golden-haired adolescent girl, part sunbaked mountain, and it is perhaps this conflation of youthful flesh and ancient rocks – of innocence and experience – that accounts for the dark circles that rim her huge, cartoonish eyes. Like an episode from a dream, or a private creation myth, we see Miss Sunset cradling a family of white rabbits in her hands, blowing on them as if to imbue them with life. Up in the sky, another teenaged female figure, pale and silvery as the moon, tangles with her own bunny, which she seems to be striking with a mallet before drowning it in a pail. This is an image, then, of the sun as life-giver, but as Aoshima reminds us, what can be given can also be taken away.

Brian Alfred, Sunlight and Personality (2017)

The great 19 th century American inventor, Thomas Edison, was an early advocate of renewable energy. ‘We are’, he wrote, ‘like tenant farmers chopping down the fence around our house for fuel when we should be using Nature’s inexhaustible sources of energy – sun, wind and tide […] I’d put my money on the sun [….] What a source of power! I hope we don’t have to wait until oil and coal run out before we tackle that’. Humanity has yet to stop chopping down its fence (indeed, the fence-chopping lobby remains frighteningly powerful), but in the 21 st century we have the ability to do something Edison only dreamed of: capture the near-infinite energy of the sun.

On first inspection, we might interpret the noted American artist Brian Alfred’s painting Sunlight and Personality as a close-cropped image of the glazed façade of a skyscraper – the HQ of multinational corporation, perhaps, or a vaguely sci-fi luxury apartment block. It’s only when we read the work’s title that we realise that it’s a depiction of a solar panel, absorbing the distant sun’s thermal energy for redistribution on Earth. If this visual chime between the architecture of the late capitalist elite and a technology that provides limitless free power feels contradictory, then this image is further complicated when we consider a key characteristic of Alfred’s painted visions of our post-industrial world: while they feature everything from cityscapes to crop circles, sports stadiums to server farms, nowhere in these canvases do we glimpse a single human being. Has some great, cleansing Rapture taken place? And if so, what might new life might flourish under this de-peopled planet’s yellow sun?

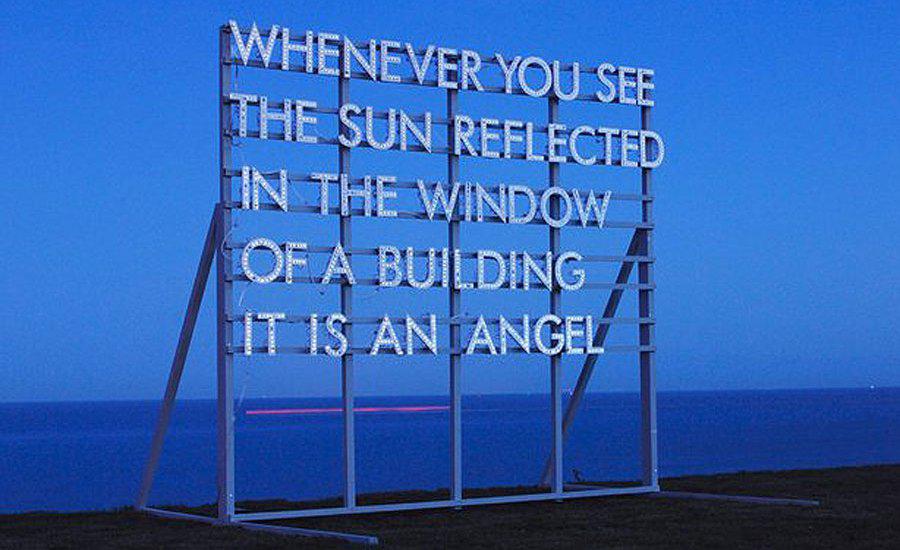

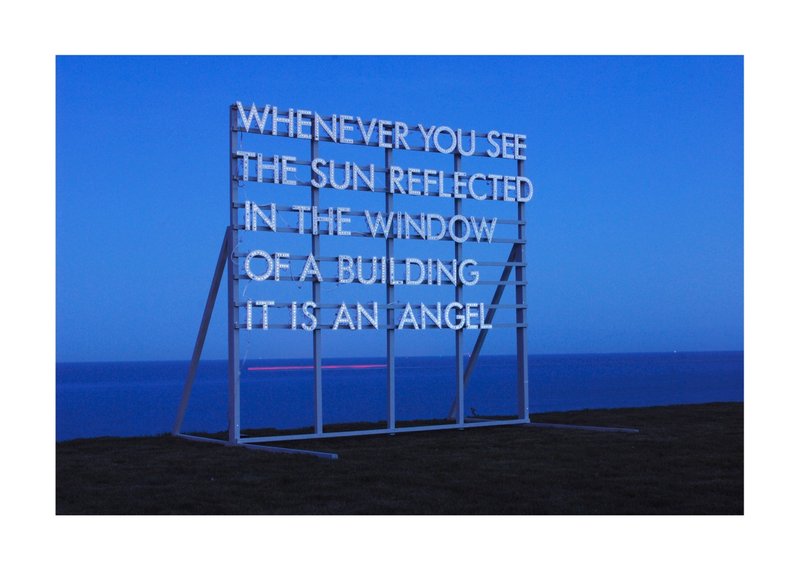

Robert Montgomery, Whenever You See the Sun (2012)

The British artist Robert Montgomery is known for his ‘light poems’, LED text works installed in galleries and public spaces that address the viewer in a voice that’s part political revolutionary, part grandiloquent self-help guru, and part doleful philosopher: ‘ALL PALACES ARE TEMPORARY PALACES’, ‘IN THE SILENCE OF YOUR BONES AND EYES FORGOTTEN MAGIC SITS AND WAITS FOR FIRE’, ‘WE ARE JUST THE WRECKED AND BROKEN TROJAN HORSES OF OUR DREAMS’. In this digital print, an armature supports the glowing words ‘WHENEVER YOU SEE THE SUN REFLECTED IN THE WINDOW OF A BUILDING IT IS AN ANGEL’, a sentiment Montgomery has said ‘is about trying to find a sense of the sacred in the everyday, a sense of God in the mundane. It seems to me it would be good for us to do that right now’.

There is an echo, here, of William Blake glimpsing angels sitting in the branches of a tree as he walked through Peckham Rye in South London (an almost comically unlikely Heaven on Earth), and perhaps of the line ‘Every time a bell rings, an angel gets its wings’ from Frank Capra’s classic movie It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). And yet, if Montgomery’s spiritual vision seems quotidian, we should reflect on how many windows the world contains, and how often we see sunbeams bouncing off their glass. There is a good reason so many faiths have associated the omnipotence of a deity with the ubiquity of solar light.

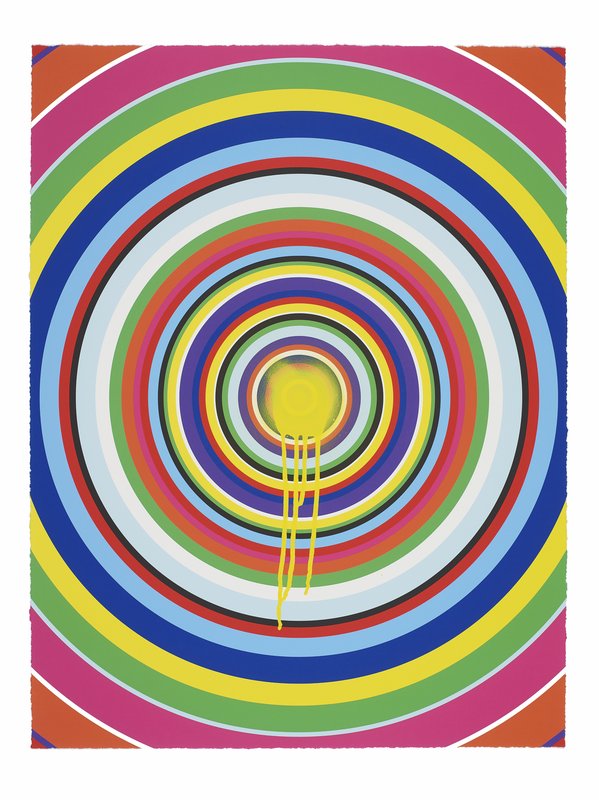

Jim Lambie, Sunspot (Yellow) (2018)

First recorded in the Chinese Book of Changes, or I Ching, in 800 BC, sunspots are the result of fluctuations in the Sun’s magnetic field, and manifest as temporary blemishes on its outer photosphere. Observing this phenomena was key to the 16 th century Italian astronomer Galileo’s then-scandalous realization that (contra the teachings of Aristotle and the Catholic Church) celestial bodies were far from flawless and immutable – ‘which news’, he wrote, ‘will be I think the funeral, or rather the extremity and last judgement, of pseudo-philosophy’. Galileo’s scientific rigour was not, of course, appreciated by the Church authorities (following his advocacy of Copernican heliocentrism, he was tried as a heretic, forced to recount his views, and spent the last eight years of his life under house arrest), but today he is remembered as the secular patron saint of all those who prize empirical observation over dogmatic belief.

The Scottish artist, musician, DJ and 2005 Turner Prize nominee Jim Lambie’s print Sunspot would have appealed to Galileo. The work’s ground is a digital rendering of a set of concentric circles, as perfect as the stars imagined by Aristotle in his 350 BC text, On the Heavens . In the centre of this target, Lambie has spray-painted a yellow dot, whose chaotic drips both contradict the strict geometry of the circles, and stir the composition into life. Is this a form of vandalism – even heresy – or is a statement of (intellectual) freedom? Perhaps, in the end, it is simply an image of the universe as it is, blemishes and all.

The Artspace Group Show: Text as Art - Art as Text

The Artspace Group Show: The Contemporary Nude