Archaeologists are accustomed to interpreting the past through its incomplete material record. Digging up shards of broken pottery, or a disembodied marble limb from a statue of what might have been a god, or a long-dead emperor, they must use these fragments to infer a disappeared and perhaps irrecoverable whole.

A fragment is a clue to what’s missing, then, but it is also something with its own fascination. It tells a partial story, freighted with ambiguities, and this creates space for speculation, even poetry. Fragments are compelling precisely because we can seldom be sure what it is they really are.

For this edition of Group Show, we bring together six works from the Artspace gallery that focus on the fragment. While several of these draw on the antique past (and its often-deceptive remnants), they also speak to a range of 21st century concerns, from rage against unbridled capitalism to environmental degradation, from the persistence of the patriarchy to the mutability of identity.

If the artists who made them are, in a sense, archaeologists, then their field of study is very much the present day.

Gillian Wearing - My Hand (2012)

Gillian Wearing - My Hand (2012)

Gillian Wearing - My Hand (2012)

At the heart of the Turner Prize winning British artist Gillian Wearing ’s practice is the question of how human beings self-present – the masks they wear, the disguises they adopt, and the possibilities of freedom these things offer. Crucially, this is not only about offering up an image of ourselves to others. As she has said: “We are all performers, we perform ideas of ourselves in our heads, project our future selves. We re-enact moments from our lives in our memories, have different ways of interacting [with people] we know and those we don’t.” Identity, in short, is not something whole and immutable, but rather a shifting, fragmentary constellation.

Wearing’s My Hand is a self-portrait of sorts, but unlike conventional self-portraits it is not a depiction of the artist’s face, but a wax cast of her right hand. On one level, her sculptural method appears to guarantee a certain degree of truthfulness. Cast a hand, and you’ll also cast a set of finger-prints – a unique physiological marker that persists throughout our lives. And yet, Wearing’s work also provides us with other, more performative indices of selfhood: a gold ring worn on the middle digit (which traditionally communicates individuality), and a set of painted nails, each of which displays a different colour, seemingly cribbed from Piet Mondriaan’s palette of reds, blues, yellows, whites and blacks. Are these adornments clues to the artist’s identity, and if so how would this identity change were she to slip off the ring, or remove the varnish from her nails?

David Beattie - Broken Tools (Donnybrook) (2019)

David Beattie - Broken Tools (Donnybrook) 2019

David Beattie - Broken Tools (Donnybrook) 2019

In medieval iconography, tree stumps are associated with a passage from the Old Testament Book of Isaiah, which prophesizes that the ‘rod’ of Christ will ‘come forth […] out of the stem’ of the messiah’s ancestor, Jesse. Fast forward to the late 19th century, and a vogue emerges for stump-shaped grave markers, indicating a life cut short. Continuity and discontinuity, the promise of an undying savior and the possibility of an all-too-sudden demise: in symbolic terms, the tree stump is profoundly ambiguous. This is to say nothing of the way the ringed cross section of a felled trunk speaks of the unstoppable march of time.

In his photograph Broken Tools (Donnybrook), the Dublin-based artist David Beattie captures a tree stump in a southern district of his home city. Cut close to the ground, and with a precision that indicates the use of modern sawing equipment, it is not the accidental byproduct of some ancient lightning storm, but rather evidence of an active – and very recent – human decision. Why, then, was the tree that once stood here felled? Along the top of the image, above an intricate scree of wood chip and broken branches, there is a block of concrete. Nature, it seems, is in the process of being paved over. We’re left wondering at Beattie’s curious title, ‘Broken Tools’. Perhaps he is referring not to a lumberjack’s chainsaw (which here seems all-too effective) but to a planetary apparatus: the Earth’s green lungs.

Tom Burr - Brutal Fragment (New Haven) (2017)

Tom Burr -Brutal Fragment (New Haven) (2017)

Tom Burr -Brutal Fragment (New Haven) (2017)

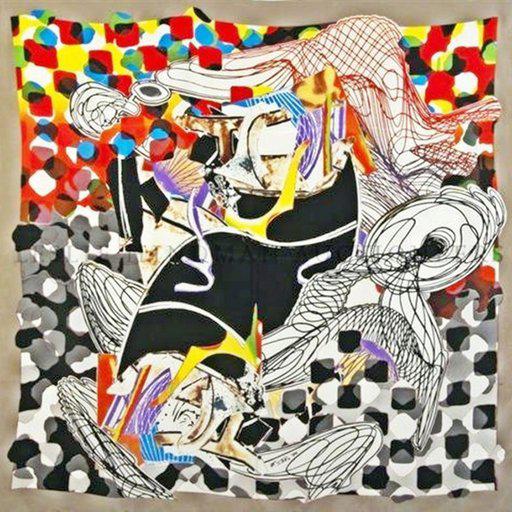

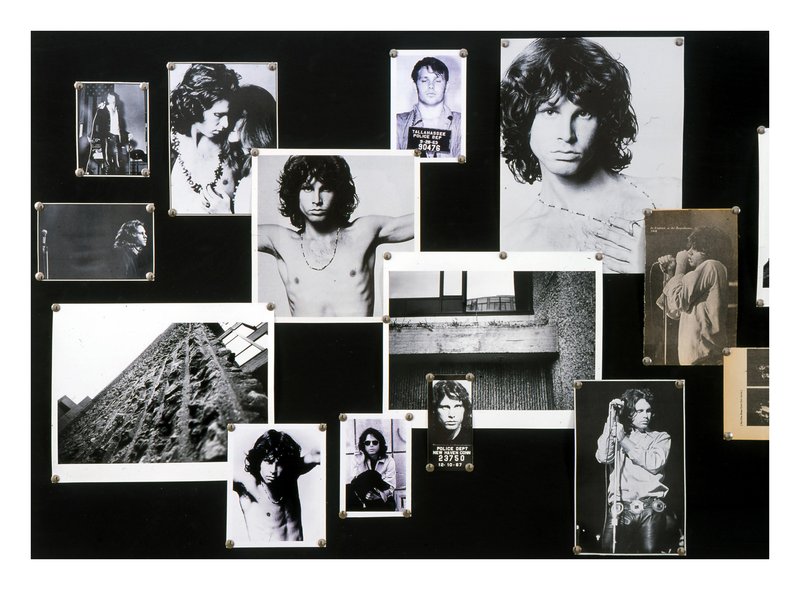

In 1926, the great German art historian Aby Warburg (1866-1929) began work on the final version of his Mnemosyne Atlas: a collection of 79 wooden panels covered in black cloth, to which he pinned everything from a reproduction of Sandro Botticelli’s painting the Birth of Venus (c. 1485) to a newspaper photograph of an early 20th century female golfer, from medieval zodiacs to contemporary ads for cologne. By juxtaposing such geographically and temporally distant cultural fragments, Warburg sought to map out what he called ‘the afterlife of antiquity’. The Mnemosyne Atlas was, he claimed, ‘a ghost story for adults’, wherein the classical past was exposed as a phantom that had been haunting the Western imaginary for over two millennia.

Like Warburg’s Atlas, the noted American artist Tom Burr ’s print Brutal Fragment (New Haven) employs a black background to bring together apparently disparate images, although his interest is less in the persistence of antique ideas and forms than in the sudden cultural rupture of the 1960s. Burr juxtaposes photographs of Jim Morrison, lead singer of The Doors, with shots of Paul Rudolph’s 1963 Yale Art and Architecture Building, a seminal work of Brutalist architecture. Burr has said that he was “interested in the latent adolescent rebellion of Brutalism”, which was masked by its association with civic institutionalism. Looking at this work, it’s hard not to think of how many Brutalist buildings were demolished when the style fell out of favor in the 1970s, and of Morrison’s own decline from Byronic Adonis to paunchy drunk as the ‘60s ticked over into a new and darker decade.

Maurizio Cattelan - L.O.V.E. SOUVENIR di MILANO (2015)

Maurizio Cattelan - L.O.V.E. SOUVENIR di MILANO, 2015

As its title suggests, Maurizio Cattelan’s L.O.V.E. SOUVENIR di MILANO is a reproduction-in-miniature of his 36-foot sculpture L.O.V.E., which the Italian artist installed in Milan’s Piazza Affari in 2010. Resembling a fragment from some vast piece of classical statuary, this work consisted of a single marble hand set on a plinth, its every digit broken off at the knuckle save for the upright middle finger. Piazza Affari is home to the headquarters of the Italian stock exchange, and when its fat cats strolled through the square (still smiling, perhaps, at how they’d escaped the fallout of the 2008 global financial crisis scot-free), Cattelan’s sculpture appeared to gesture towards them in no uncertain terms.

The Italian artist is often referred to as a jester. This doesn’t only mean he’s funny, but also that he speaks truth to power, like a medieval fool mocking a king. There’s something appealingly juvenile about Cattelan’s one fingered salute to Italy’s plutocrat class, not least its inbuilt deniability – given that this hand has but one digit, what other gesture might it make? L.O.V.E. SOUVENIR di MILANO is also a meditation on how even the most seemingly omnipotent individuals and institutions may end in ruin. The work echoes Percy Bysshe Shelley’s famous poem Ozymandias (1818), in which a ‘traveller in an antique land’ discovers the shattered remains of a statue of an ancient pharaoh. While it still bears the inscription ‘Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair’, the levelling forces of time have reduced it to nothing but a ‘colossal wreck’.

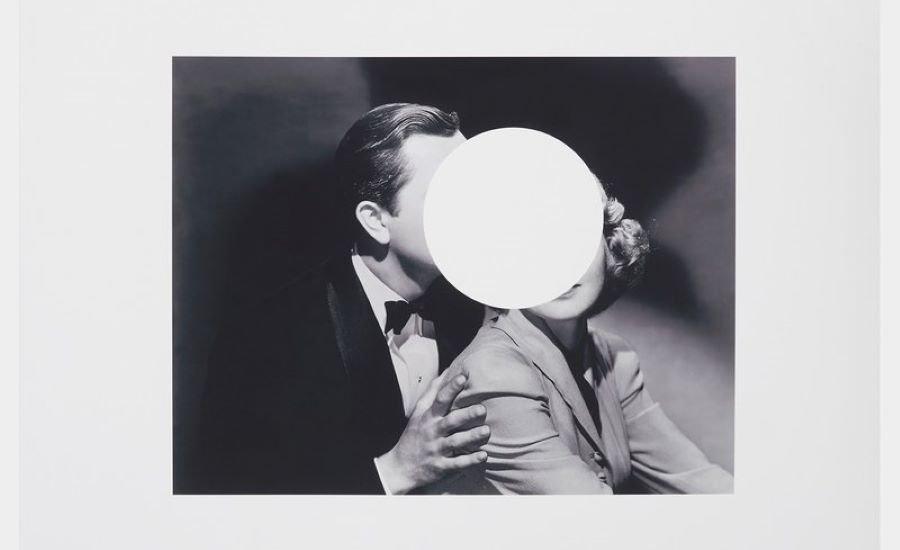

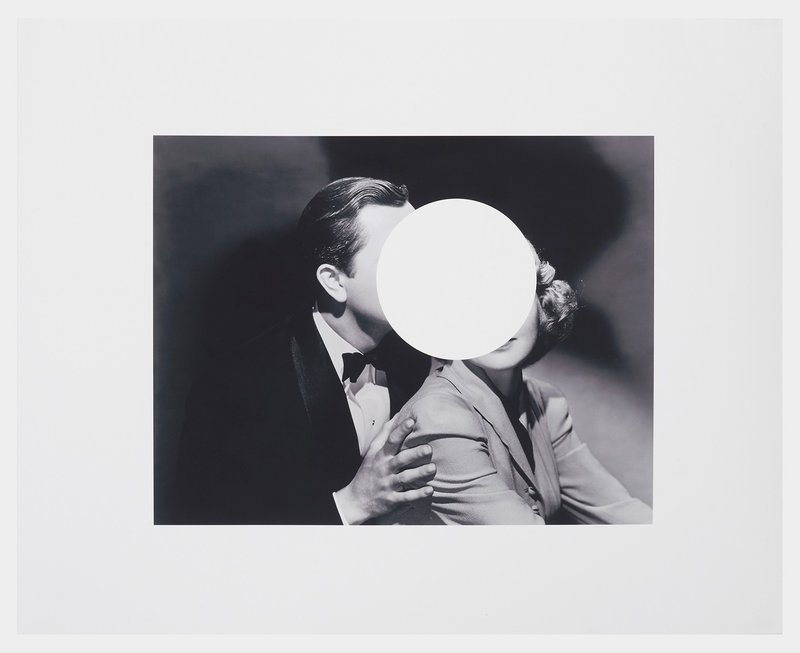

To look at a fragment is to think about absence as well as presence, about what is missing as well as what remains. For his photographic work Touch, the leading British artist John Stezaker cut a circular hole in a vintage film still of an elegantly dressed young couple, removing their facial features. This modest action has a profound effect on how we read the image. Unable to see the couples’ eyes or lips, we have no secure visual grip on their personalities, or their emotional state. Are they happy to be together, or desperate to separate? Searching for clues, we scan what remains of the film still. Is the man leaning into the woman to kiss her temple, or to whisper a threat into her ear? Does he clutch her shoulder out of passionate desire, or to prevent her escape?

Without the missing piece of the puzzle, there are no real answers to these questions. Any theories we might advance are necessarily provisional, and in the end reflect only our own temperaments and prejudices. Touch is part of a larger series by the artist that’s collectively titled Tabula Rasa. Often translated as ‘blank slate’, this Latin phrase refers to the proposition that human beings are born without innate knowledge. It follows that our understanding of the world depends upon perception, and the experiences we accrue. The absent section of Stezaker’s film still, then, might be thought of as cinema screen of sorts, on to which we project nothing more than our own, contingent selves.

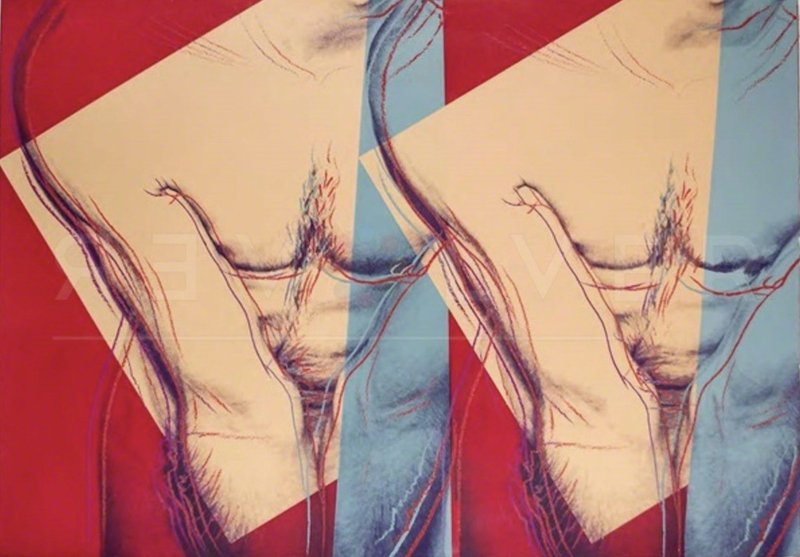

The Western World’s first recorded stash of pornographic material arguably belonged to the Neapolitan Royal Family, who in the 18th and 19th century maintained a ‘Gabinetto Secreto’ (or ‘Secret Cabinet’) filled with erotic Roman friezes, statues and objets d’art discovered in the ruins of Pompeii. Among these items were representations of the god Mutunus Tutunus, or as the Greeks referred to him, Priapus: a fertility deity notable for his gigantic, permanently erect phallus.

Resembling at once an archaeological find, a double-ended sex toy, and a vaguely Henry Moore-like modernist sculpture, the celebrated British artist Sarah Lucas ’s cast plaster sculpture Priapus appears to be a totem to this virile, somewhat ridiculous immortal. It is not, however, intended to be a conduit for uncomplicated reverence.

Lucas’ work fuses together casts taken from parts of two larger wholes: the rough-hewn handle of a sword of undisclosed provenance, and the tumescent penis of an anonymous man. This conflation of weapon and phallus is of a piece with her customary blurring of metaphor and literalism (think of her 1992 sculpture of a female form Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab, whose materials were dictated by slang terms for the breasts and vulva). It is also the motor of Priapus’s deflationary humour. Lucas, who represented Britain in the 2015 Venice Biennale, employs the notion of the fragment to question the equation of male aggression with male potency. A penis requires a heart, after all, to pump it full of blood. Disconnected from this loving organ, it becomes useless – a sword hilt without the blade.

RELATED STORIES

The Artspace Group Show: Text as Art - Art as Text

The Artspace Group Show: The Contemporary Nude