What’s in a word? Since at least the development of synthetic cubism, which saw Pablo Picasso incorporate newspaper banners into paintings such as Still Life With Chair Caning (1912), text has been a key subject – and material – for 20th and 21st century artists. We might think, among other examples, of René Magritte’s playful juxtapositions of lexical and visual information in his canvas The Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (1929), the investigations into the philosophy of language carried out by the 1960s Conceptualist Joseph Kosuth, and the politically charged practices of Barbara Krueger and Jenny Holzer, which interrogate the (often intertwined) vocabularies of patriarchy and consumer capitalism to searing effect.

In the first of a new Artspace series, Group Show, we gather together six works from the Artspace store that probe the written word. Text, in these pieces, becomes everything from a magical incantation to an (almost) abstract graphic mark, an unwelcome presence to an unnerving absence. What connects them is their insistence on both the potency of language, and its inherent instability.

And, of course, their affordability. The cheapest is $400 (£300) the most expensive $4,500 (£3,500) with plenty of variation between. You can pick them all up from our store.

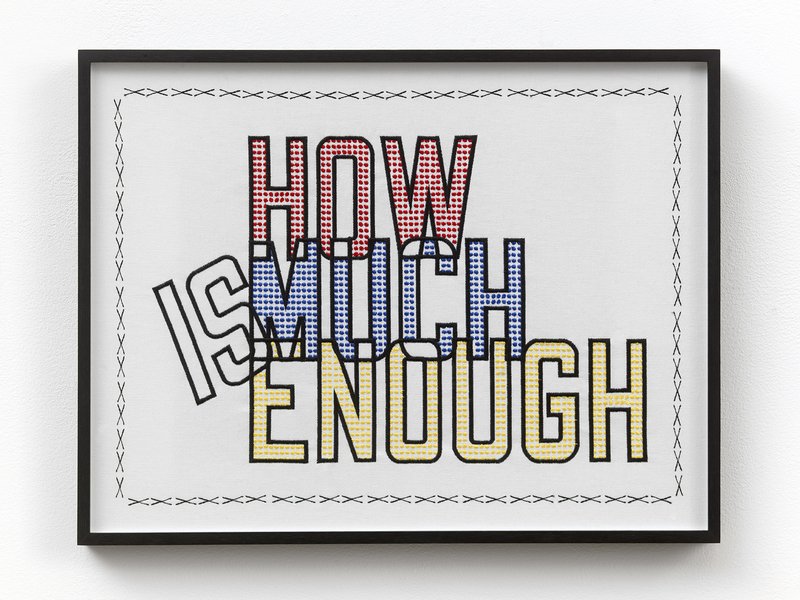

Lawrence Weiner - How much is enough (2014)

Lawrence Weiner - How much is enough (2014)

Early in his career, the American artist Lawrence Weiner wrote that ‘I do not mind objects, but I do not care to make them’. Arguably the most radical of his pioneering generation of Conceptualists, his practice is characterized by its steadfast refusal of conventional art production, instead employing language as a ‘sculptural material’ in text-based pieces. These have included both sets of instructions that do not necessarily need to be followed in order to constitute a completed art work (for example his 1968 ONE PINT GLOSS WHITE LAQUER POURED DIRECTLY UPON THE FLOOR AND LEFT TO DRY), and sentences stenciled directly onto a wall (his 1986 WATER UNDER A BRIDGE, which evokes its titular river crossing in the viewer’s mind without the artist making a single image or object).

Weiner’s work How much is enough (2014) resembles an embroidered sampler, of the type used to demonstrate skill in needlework. Beyond its upending of received distinctions between art and craft, and of outmoded ideas concerning masculine and feminine forms of creativity, the piece also seems to pose a query about artistic labour. We should note, however, the absence of a question mark at the end of Weiner’s sentence. Trying to make sense of this, our minds transform the word ‘How’ into ‘This’, or perhaps even ‘Too’, but the embroidered letters remain stubbornly the same.

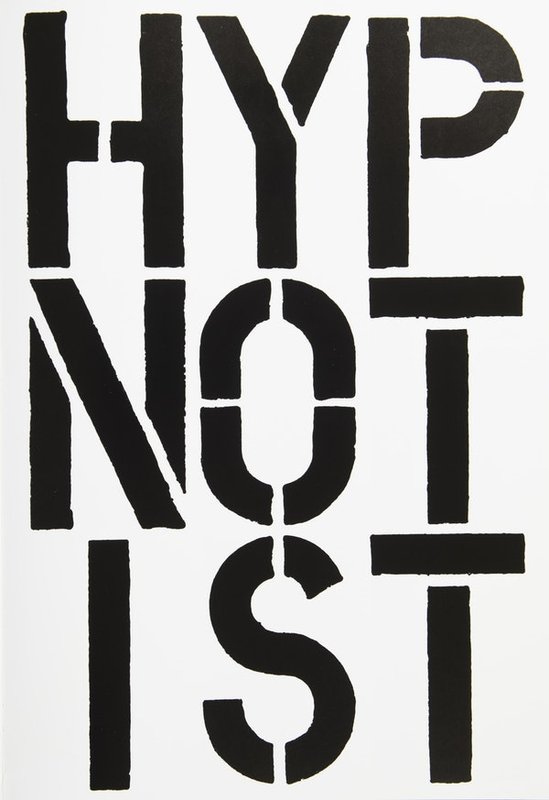

Christopher Wool - Page from Black Book (Hypnotist) (1989)

Christopher Wool - Page from Black Book (Hypnotist) (1989)

Widely considered to be among the world’s most important living painters, Christopher Wool began making text pieces in the wake of the 1987 stock market crash. Perhaps the most iconic among these is Apocalypse Now (1988), which urges us to ‘SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS’ in blocky black capitals, stenciled on to a white ground. Significantly, the American artist has said of these works that: ‘They were a little bit political. But I really did see them first as paintings’, and therein lies their pointed challenge. Can we circumvent our instinct to ‘read’ them as texts, and instead ‘see’ them as formal compositions, or will the language habit always prevail?

Produced for Wool’s celebrated limited edition 1989 artist’s publication, Black Book (images from which were exhibited in the artist’s 2013 retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim museum), Page from Black Book (Hypnotist) (1989) arranges the word ‘HYPNOTIST’ into a skewed, nine-letter grid. By breaking it up into three distinct lines of text (one of which, ‘NOT’, is a word in its own right), Wool slows down our ability to ‘read’ the work as a piece of writing. Our eyes linger on the letters’ play of verticals and horizontals, their ragged, screen printed edges, their purposefully uneven spacing. At the same time, his invocation of the hypnotism – a practice in which verbal prompts induce altered mental states – attests to the power of language.

Annika Ström - Please Help Me – Blue (2005)

Annika Ström - Please Help Me – Blue (2005)

Annika Ström - Please Help Me – Blue (2005)

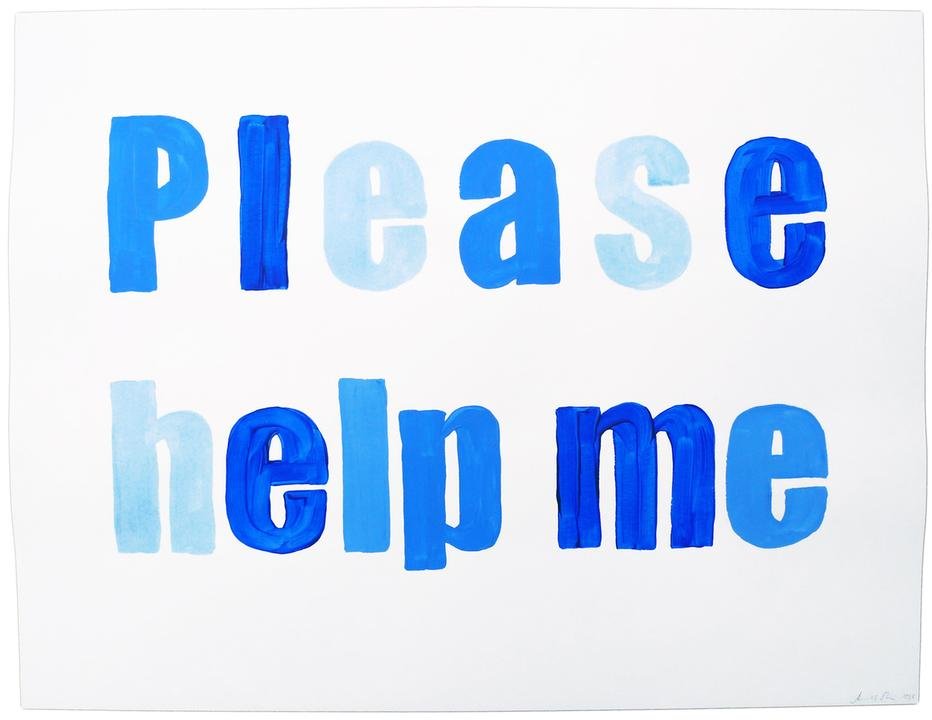

The work of Annika Ström – which comprises videos, performances, and musical compositions in addition to witty, often emotionally blindsiding text pieces – combines conceptual rigour with a fascination with the hopes and insecurities that haunt the human heart. Painted in gouache on paper using a handmade stencil, her language works included garbled nods to their art historical antecedents (this work refers to Joseph Kosutt), reflections on their own display (this work is has gone up), and bald assertions of the economic role they play in Ström’s life (this work was made to support me). Such seemingly straightforward statements are balanced by, or at least juxtaposed with, text pieces that seem to issue from some unguarded part of the artist’s psyche: oh, I so much want to make a piece of political art; everything in this show could be used against me; I am a better artist than I deserve.

Please Help Me – Blue (2005) is, of course, a plea for assistance, but Ström does not disclose why, or how, or from whom she requires aid. It is this ambiguity that gives the work its universality: all of us need help, now and again, even if we don’t recognise it ourselves. And yet, the artist’s careful stenciling and use of three different shades (from a turbulent cerulean to a pale sky blue) undercuts the urgency of her message. Rarely do appeals for succor appear this poised.

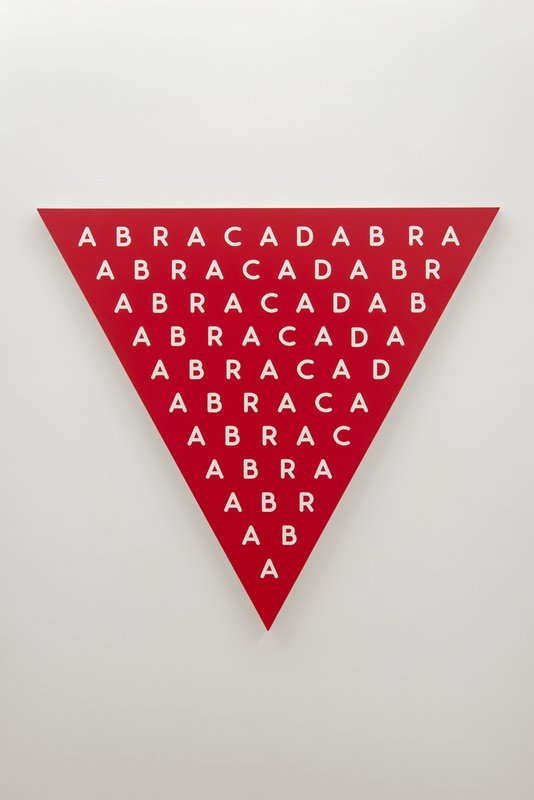

Donald Morgan - Universal Spell (2016)

Donald Morgan - Universal Spell (2016)

Children’s literature teaches us that certain words are imbued with supernatural powers: ‘hocus pocus’, ‘open sesame’, and perhaps above all ‘abracadabra’. While we now associate such language with little more than fairy tales, this last incantation has deep historical roots. Linguists have claimed that ‘abracadabra’ is derived from the ancient Hebrew phrase ‘I will create as I speak’, and it was used as a magical formula by the 2nd Century Gnostic sect, the Basilideans, to invoke the help of beneficent spirits against misfortune and disease. The practice was echoed in the medical advice of the Roman physician Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, whose textbook Liber Medicinalis recommended that malaria suffers wear a triangular amulet, on which was written this most potent of enchantments.

Like Sammonicus’ talisman, the American artist Donald Morgan’s painting Universal Spell arranges the word ‘abracadabra’ into a tapering triangle, the white letters and red background suggesting a curative purpose. His c hoice of font speaks not of arcane spell books, but of Bauhaus rationalism, and we might at first glance mistake the work for an optician’s chart, which uses letters of the alphabet to test a patient’s ability to perceiv e the physical, rather than metaphysical, world. Nevertheless, Universal Spell (2016) is a painting about the power of language in the 21st Century: how it might heal, or how it might harm.

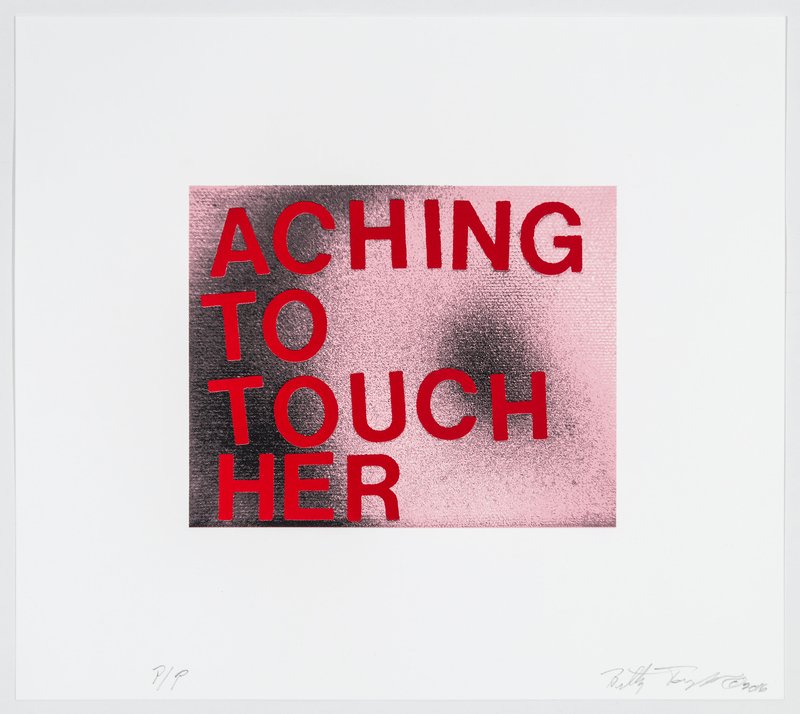

Betty Tompkins - Aching to Touch Her (Print) (2016)

Betty Tompkins - Aching to Touch Her (Print) (2016)

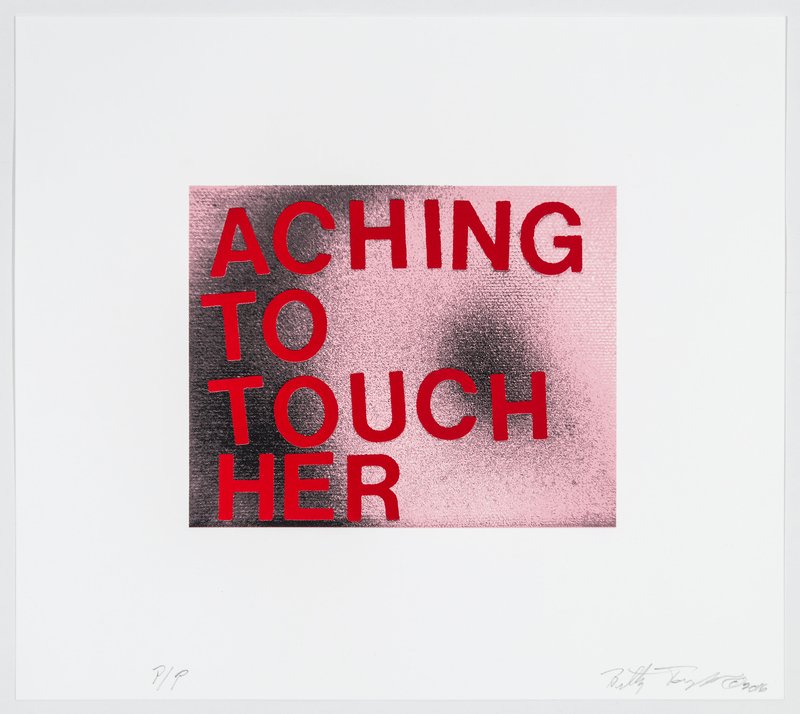

Based on a painting included in the seminal American artist’s 2016 exhibition WOMEN Words, Phrases, and Stories at the FLAG Foundation, New York, Betty Tompkin’s Aching to Touch Her (Print) reflects on the way men use language to objectify and dominate women, framing them through both desire and reproach. The work’s title and featured text is drawn from a vocabulary of some 3,500 terms and phrases crowdsourced by the artist. Tellingly, when she made her emailed appeal for ‘words to describe women’, first in 2002 and then again in 2013, the four most common responses were ‘Mother’, ‘Slut’, ‘Bitch’ and ‘Cunt’.

Compared to some works in the WOMEN words… series, Aching to Touch Her (Print) (2016) may appear relatively innocuous, echoing as it does the hackneyed poetic trope of love (or at least sexual attraction) as a kind of pain. And yet, the way Tompkins lays these words in shaky, blood red script over the image of blurred breast is a reminder of the violence they contain. What is privileged, in this phrase, is the male ‘ache’, not the female body, which is reduced to an anonymous site of relief. Note how the ‘C’ of ‘TOUCH’ seems to pinch the nipple of the disembodied breast. These WOMEN words… are less an expression of romantic yearning, then, than a presage of assault.

Like anybody who has passed through the British education system, the emerging young sculptor Jesse Wine is all too familiar with the lined white pages of the exercise book, complete with their red-rimmed margins, in which a teacher might scribble criticism or praise. In Homework, he recreates a single sheet of composition paper in glazed ceramic, its surface a little crumpled, its bottom left corner turning in on itself, as though in muted shame. Strikingly, no words appear anywhere on this page. Perhaps the titular homework has not been started yet. Perhaps it never will.

The absence of text in Wine’s work might be understood as an act of resistance against teacherly authority, or as an image of scholarly or even creative anxiety – with so many words available, and so many ways in which they might be combined, choosing how to begin a sentence can feel like an impossible task. And yet, this page is not a ‘blank canvas’: lines and margins are nothing if not methods of control, designed to give thought a particular shape. Looking at this work,

Homework (2018) , its determinedly analogue nature feels important, in an age when digital technology has impacted on sculptural practice as surely as it has on pedagogy. A ceramic page is much heavier than a piece of paper, or indeed an encyclopedia’s worth of data. Wine, it seems, is asking us to meditate on the weight of (no) words.

Scroll through the module below to take a closer look and buy the work you've just read about. The cheapest is $400 (£300) and the most expensive $4,500 (£3,500) - with plenty of variation between.