Displaying art properly is not as simple as hammering a few nails and hanging a painting. For collectors operating in the upper echelons of the art world, making home a worthy setting for their treasures requires a specialized touch±—one that Chris Stone and David Fox of the architecture and design firm Stonefox are prepared to provide. Partners in life as well as business, the pair specializes in creating modern spaces that infuse the comfort and intimacy of the domestic with the intellectual and aesthetic insights offered by contemporary art. Clients have included such art-world power couples as Amy and John Phelan and Mickey and Jeanne Klein .

Artspace’s Dylan Kerr met up with the pair—accomplished collectors themselves—in their art-filled NoHo office to discuss the firm's history, their ambitious new design projects like the Whisper Raum, and why saying an artwork “looks good over a sofa” isn’t such a bad thing.

Rendering featuring works by Asumme Vivid Astro Focus, Leila Pazooki, John Salvest, and Thomas Hirschhorn

Rendering featuring works by Asumme Vivid Astro Focus, Leila Pazooki, John Salvest, and Thomas Hirschhorn

Your firm is known for designing spaces with the display of contemporary art in mind. How did you get started operating at this intersection of architecture and art?

DF: I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that I previously worked for another architect, and I was the project architect for a house in Santa Fe for Mickey and Jeanne Klein. At one point, we needed somebody to do the interior design, and at the time Chris was working for Rafael Viñoly on

Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn

’s [of

Salon 94

] townhouse. The Kleins knew of Jeanne, so I said, “I’m dating this guy who’s working on Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn’s house, and he’d like to do his own work.” Chris had this idea that we would curate all the pieces furniture as one-off designs by emerging designers, and Jeanne Klein was like, “Oh my god, I love that idea!”

It didn’t work out exactly that way, but he ended up leaving Viñoly and working there. The Kleins were really the intro to working more extensively with collectors, because they have an important modern and contemporary art collection. Their daughter-in-law is Lora Reynolds, who owns

a gallery

that we ended up doing as well. Lora introduced us to John and Amy Phelan, who recommended us to a lot of people. One thing just led to another—it just sort of worked out.

There are certainly architects out there that have a reputation for being like, “Don’t put anything on my walls!” They’ll put lots of surfaces on their walls that make it hard to hang something, or say, “That’s a wood wall—you can’t hang anything on a wood wall!” We encourage our clients, and they like to hang a lot of things. Someone who’s a collector doesn’t want the architecture to get in the way.

Rendering featuring works by Leila Pazooki

Rendering featuring works by Leila Pazooki

Jumping off that, how is your approach different when designing a building that you know you

’

re going to be showing or hanging art in?

DF: We think about art from the very beginning. For big collecting clients like the Phelans, we do a review of their collection and a list of their biggest pieces, and we kind of work from the biggest to the smallest to figure out how larger our walls need to be in order to handle some of the more sizable pieces they have.

So you actually design around specific pieces in their collections?

CS: Yes, definitely. We’ve worked with so many different collectors and so many different impulses, residential or otherwise, but I think there’s two main veins: the collector who has a very developed sense of luxury, so the art is seen in a domestic context, or the collector who lives in a museum. This is something that comes out of the ‘80s and ‘90s, this whole reductive, minimalist approach of someone like John Pawson, where the architecture becomes almost invisible and the art takes front and center.

When I was an art student at RISD, we would make fun of people’s work by saying it would look really great over a sofa. That was a cut, but here we are thinking about art in the domestic space and I actually think it’s more interesting. When I was working for Viñoly on the design for Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn’s townhouse, she installed this

Kara Walker

mural in her dining room, so the fireplace was right in the middle of the mural.

You would think it would be a “that would look great over the sofa” kind of thing, but the work actually became way more meaningful—this was a piece about American slavery installed in an Upper East Side townhouse. There’s a certain layering, where placing the art in a new context allows the meaning to change. I can’t tell you exactly what it means, but it made me think about the work a lot more than if I had seen it in a museum or a gallery.

I think the same is true with another client’s home in Aspen, where

Jenny Holzer

’s

Truisms

come up through a column. Some of them say things that are actually very critical of people that are part of this high culture, like, “Money doesn’t buy taste.” That’s not very interesting to read in a museum—it’s far more interesting to see in the intimacy of a domestic environment. Again, I can’t tell you what it’s going to mean, but it challenges you to think.

DF: There was an impulse—one that I think still exists—where collectors say that they want a clean, minimal space for their works, like a gallery or a museum. Designing the way we’ve been talking about, integrating the works into the domestic context itself, is actually much harder. Designing a luxurious, beautiful, ephemeral interior that also works for artworks is not easy. Trying to make an art museum homey—the scale is not right for that. That has been a struggle. We’re getting there, but it hasn’t been that easy.

CS: When we go into a gallery and say that we’re looking on behalf of a client, it’s been surprising for us how often the first or second questions from the gallerist will be, “What size? What format? What color?” It’s amazing how they’re ready to serve like that. We’re like, “No, that’s not how we do it.”

Rendering featuring work by Rob Pruitt

Rendering featuring work by Rob Pruitt

How involved are you in choosing the art that goes into the spaces you

’

re designing?

DF: In some cases, we do everything. The architecture, all the furniture, and then we help them collect art—with mixed success, I would say. Choosing art for somebody is like dressing them, it's very intimate. You’ll think, “Oh, my client is going to love this because he or she showed us this reference,” but when they see it in person they don't like the drips or brush strokes. It’s highly subjective.

Other clients are collecting on their own, but we do get involved in what goes where as we’re coordinating the installations. They do appreciate our opinions and invite us to be a part of the process.

CS: There are a lot of practical concerns. You have to think about scale, about light exposure, about whether the pieces can even get into the house. And picking the right art can really energize the architecture. With some of the early projects we did, we’d see the furniture and stuff our clients would bring in after we finished and say “Really?” We’d have to bring things in to prop the space just to shoot it.

For us, this dialogue between the art and the architecture is really interesting, whether it has to do with more decorative aspects or a more social or cultural function. Either way, I think it’s really important. For clients that entertain often, the art forms a very intimate social function. It has a narrative about who they are, and it has the potential to either ricochet and become energized against the architecture or recede to become part of the space.

DF: This reminds me of when we did my brother’s house in Austin. He’s a neurosurgeon, and he’s what you would imagine a neurosurgeon would be like [laughs]. He’s intense, and he wanted a beautiful house. I was helping him collect art too, and we got some interesting works for him. Their dining room is quite traditional, but I found these abstract paintings by Katy Cowan from

Cherry and Martin

for him.

He looked at them and liked the abstract imagery, but when they arrived he noticed that they were painted with a light-sensitive paint that will pick up shadows—the imagery is of bricks or hammers. My brother sees them in his traditional dining room and says to me, “Is this right?” I’m like, “Yeah, and people will think you're cool for it—it's a joke, but it's making a point.” Everything else in there is kind of pretty, and it’s nice that those weren’t really behaving and didn't just blend in. They really make a statement.

You recently finished your work on something called the

Whisper Raum

, the "intimate architectural retreat" you've designed as a kind of luxury room-within-a-room. What can you tell us about this project? How does it and other like it fit into Stonefox

’

s mission?

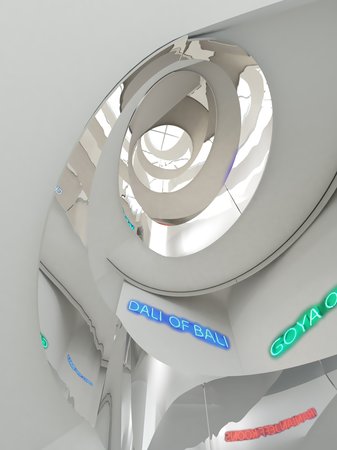

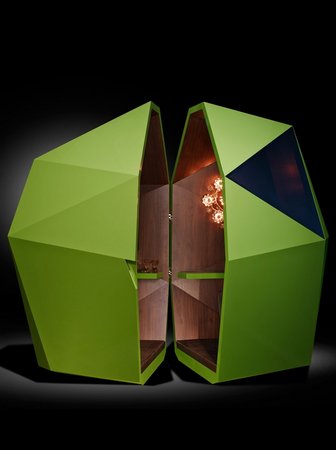

DF: We call these self-initiated projects, or “explorations.” Basically, that came out of a feeling of frustration with always having to work with a client and just wanting to do something without a client. We wanted to do something that we could hopefully push in a direction where people would come to us for what we do, as opposed to being solely service driven. We went to see the Cheapside Hoard in the Museum of London, which is this cache of intact 15th- and 16th-century jewelry that had been found under the street in Cheapside. There was this one emerald that was hollowed out and had a watch inside—it was amazing.

The other inspiration comes from the Sir John Soane's Museum in London. He’s really the father of modern collecting the way we think of it—he collected architectural fragments from all over the world and reassembled them in his townhouse. There’s all these weird little spaces in there. There’s one place you enter—he must have taken a cupola from a building that had Palladian windows—where you’re suddenly in this other space within a space. With the Whisper Raum, I was thinking that maybe it could be in our apartment, so that Chris or I could just go in there and be in the same place, but not in the same space.

CS: It was sort of the inspiration of the moment. We saw that jewel with the watch inside and thought, “What if we could get inside of this gem and close ourselves in away from the world?”

DF: We donated the finished piece to the Aspen Art Museum, who sold it to a collector in London. I didn’t really think about it, but it actually came full circle in that way.

We also have some more things that we’re working on. This summer we have a suite of mirrors that are inspired by this project, which will also be sold at the Museum at ArtCrush. There are other things that we’re making too that we haven’t finished but that hopefully we’ll get to.

The Whisper Raum

The Whisper Raum

Is this a direction you

’

re heading as a business, or is this solely something you do for yourself?

DF: I think of it as a parallel project, but I hope that something comes out of it. I think that it’s hard to find your way in the world—how are you going to get to where you’re going to get? People find all kinds of different ways to get there, so who knows exactly where it will lead?

You two are art collectors yourself. What kind of work are you interested in?

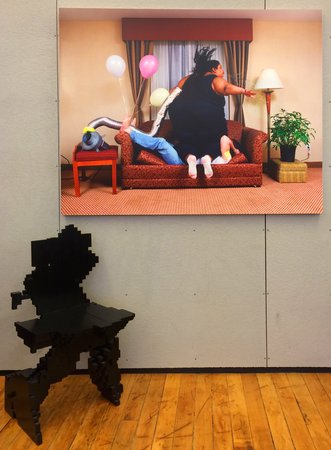

CS: We like things where the narrative may initially come out and slap you in the face, but then there’s something more to discover or get out of the work. One of my favorite pieces is this

Mika Rottenberg

, which we got at Frieze London in 2006. It used to be very prominently displayed in the office, and everybody that walked in—from a delivery person to an art collector—responds to that. It totally grabs you, but if you know about Mika Rottenberg and you know about her work, it has a lot to do with the position of women and labor in our society.

This particular woman is paid to crush, which is actually a fetish. The guy that’s underneath her has his tattoo covered in tape to hide his identity. In any case, this is something that she really does. It’s somewhat staged, but it’s also a record of a cultural practice. I always think that’s something that’s really exciting, something that people can relate to on different levels. Some people come in and just start dying laughing, because it is kind of funny.

Mika Rottenberg's

5 Second Party

(2006), with a Best Test 1-400 Chair by Philippe Morel.

Mika Rottenberg's

5 Second Party

(2006), with a Best Test 1-400 Chair by Philippe Morel.

You have a good amount of art on view here at the office. Why is that? What does art bring to the workplace?

CS: Back in 2006, we had a space about this size with less staff, so we decided to give over part of the space to young curators to come in and do a show. We did it for a year, and it was way more expensive than I could have ever imagined. Even printing invitations and hosting opening parties was expensive, and then there was shipping. On top of it all a lot of the artists were young couldn't afford to print their work, so we were helping with that too.

DF: We were really kind of a gallery. We called it Stonefox Art Space.

So you were actually funding these curators to put on these shows?

CS: As it turned out, we did [laughs]. That wasn’t really the plan, though.

DF: At first we thought it would be fun, to have some friends put some art in the office and try to get our clients interested. The first solo show we had was

Alex Da Corte

, and it was his first solo show too. We actually did sell a lot of his work. As we got to know these people, we thought that we should try even harder to promote them, so we hired someone to design the logo, someone to make a website, someone to design each invitation, someone to write to write the press release. It was crazy.

CS: We developed an enormous amount of respect for gallerists. At the same time, it was such a pleasure to have fresh art every three months. What does art bring to the office? It brings pleasure.