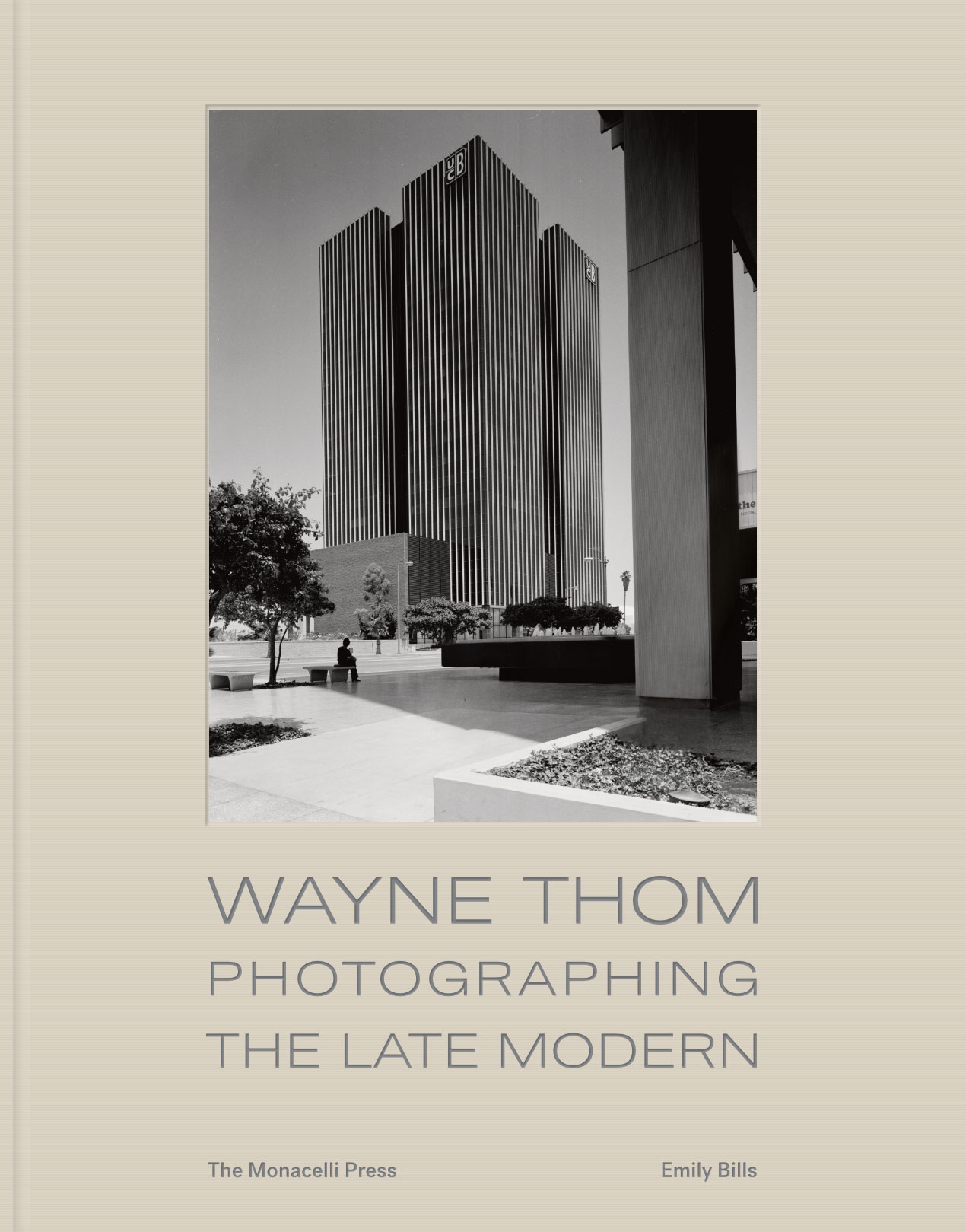

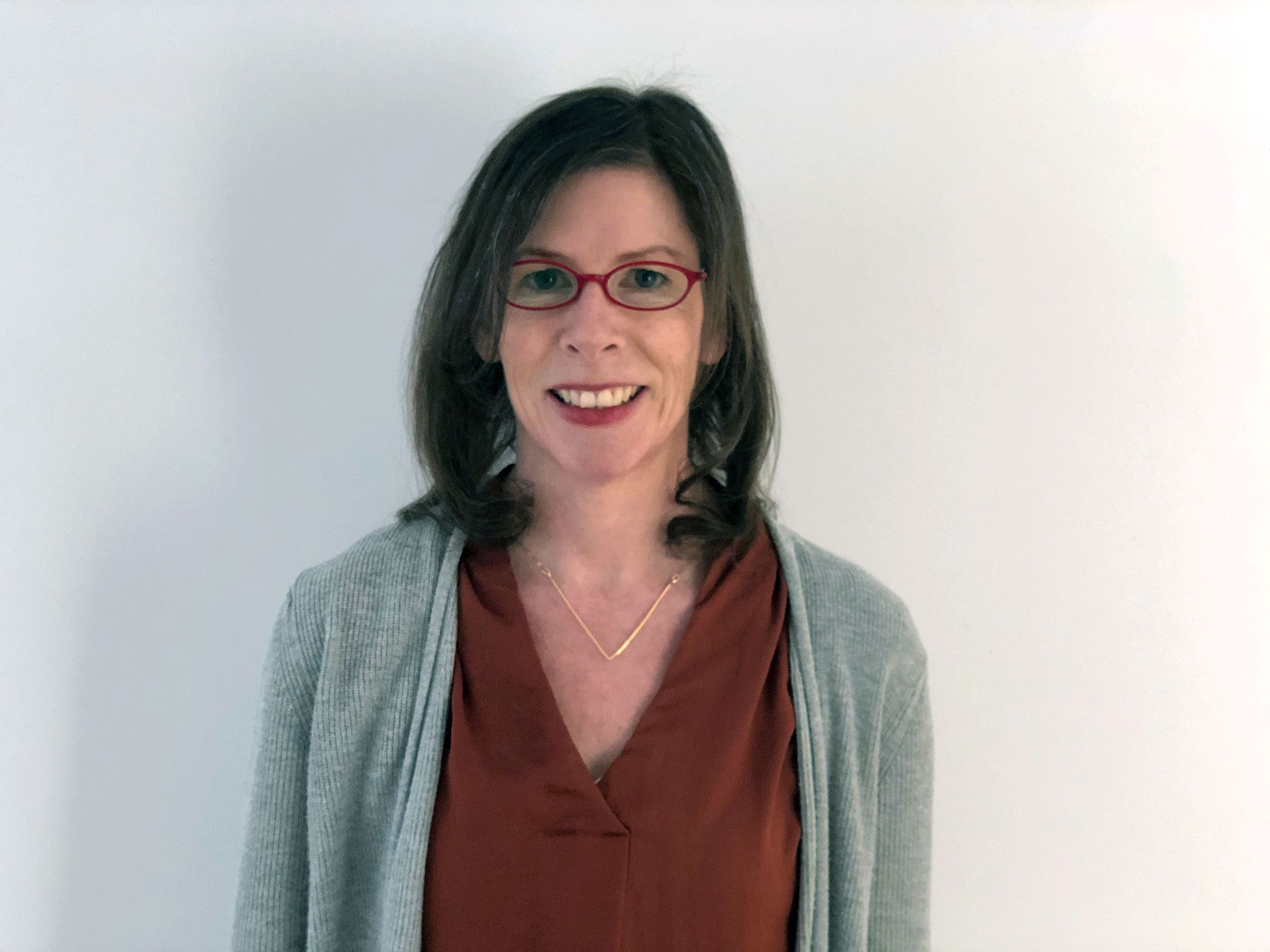

Emily Bills understands image making in the urban environment. The writer, lecturer and curator is Participating Adjunct Professor of Urban Studies at Woodbury University in Burbank, Los Angeles, and is author of Wayne Thom: Photographing the Late Modern, a Monacelli Press monograph on the leading 20th century photographer, who documented the creation of many of LA’s architectural landmarks.

However, she is also interested in the way we adorn the insides of our buildings, and, to mark the publication of her new book, she has picked out some of the works she most admires in the Artspace archive. Read on to discover how Carrie Mae Weems , Agnes Martin , Catherine Opie , Candida Höfer and James Welling have all found a place in her heart - and in her home.

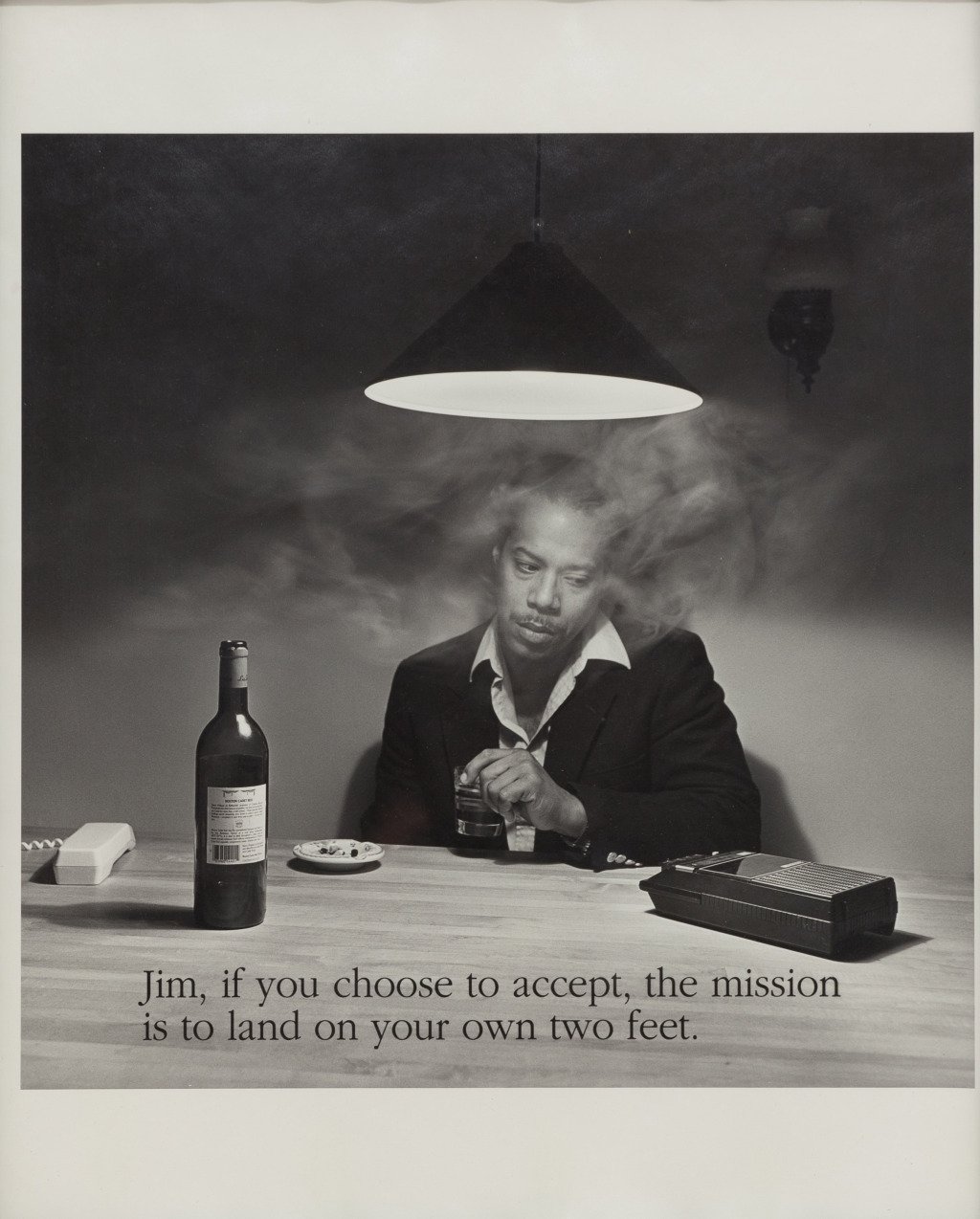

Jim, if you choose to accept... (1988—1989) - Carrie Mae Weems

There are certain works that mark significant shifts in my own art education. I first saw Carrie Mae Weems’ Kitchen Table Series as an undergraduate at Berkeley and it undeniably solidified my desire to study photography. I was struck by how such simple staging and word choices could elicit depth of meaning, and how Weems imbued every photograph with empathy. In a single image she delineates complicated interpersonal relationships while at the same time laying bare the everyday struggles faced by Black Americans. As a young student, Weems’ work impressed upon me that my interests in social justice and visual culture were not opposed, and that studying photography opened an opportunity to engage both. What I didn’t realize until much later was how much the physical environment in this series, the way interior design is carefully crafted as part of the storytelling, also influenced my eventual interest in architectural photography.

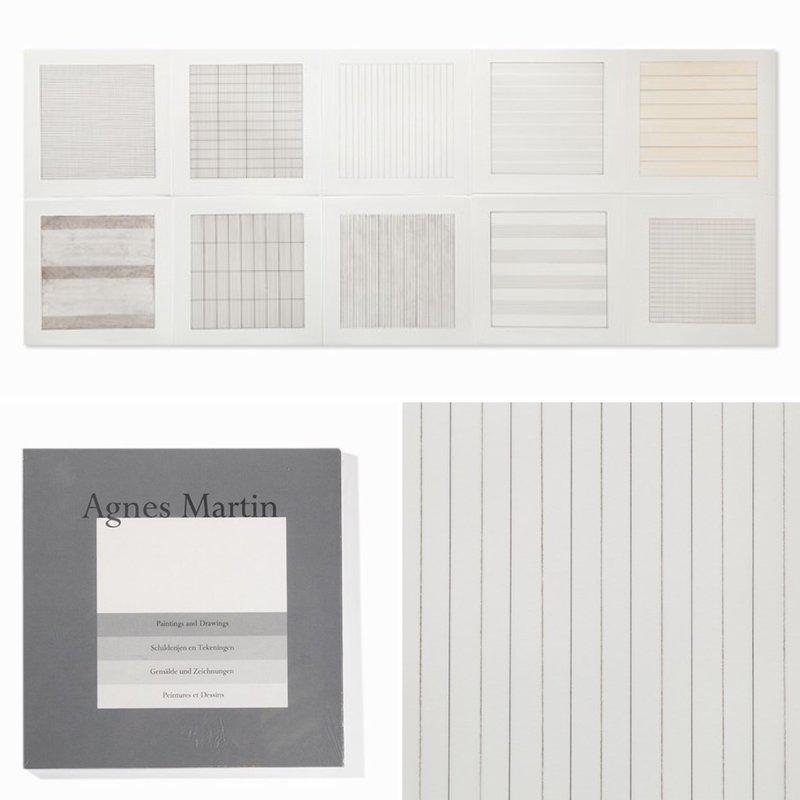

Untitled (from Paintings and Drawings: 1974-1990)

, 1991 - Agnes Martin

Untitled (from Paintings and Drawings: 1974-1990)

, 1991 - Agnes Martin

I’ve always been drawn to Agnes Martin’s minimalist works, but sometimes how art is organized in space can enhance the viewing experience exponentially. For me, this is true for the Agnes Martin room at SFMOMA, where the works are hung one each to a wall in a small, hexagonal space, much like a chapel (a curatorial approach also used to display Martin’s work at The Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, NM). The installation is a testament to smart curators who take time to consider how architecture, art, and viewer interact. As a result, I can spend hours in this room and see something new in her work each time.

Opie is known for her portraits of people, but her photographs of the built environment are also compelling. I am particularly drawn to works where she merges these two interests; my favorites are her photographs of shopkeepers in her More American Photographs series. This photograph of Bravo was taken in her own Los Angeles neighborhood. It shows a side of L.A. that only Angelenos really appreciate, that ordinary and everyday streetscape where handmade signs and small, cluttered shops serve the needs of local communities. Her photographs are a wonderful homage to working life, reminiscent of the Farm Security Administration photography project. The photograph also shows Opie’s skill at bringing out details in physical environments that help us see them in new ways. Here, the patterns and abstract motifs made by tools and hardware are as much a part of this photograph as Bravo himself, person and space merged into one.

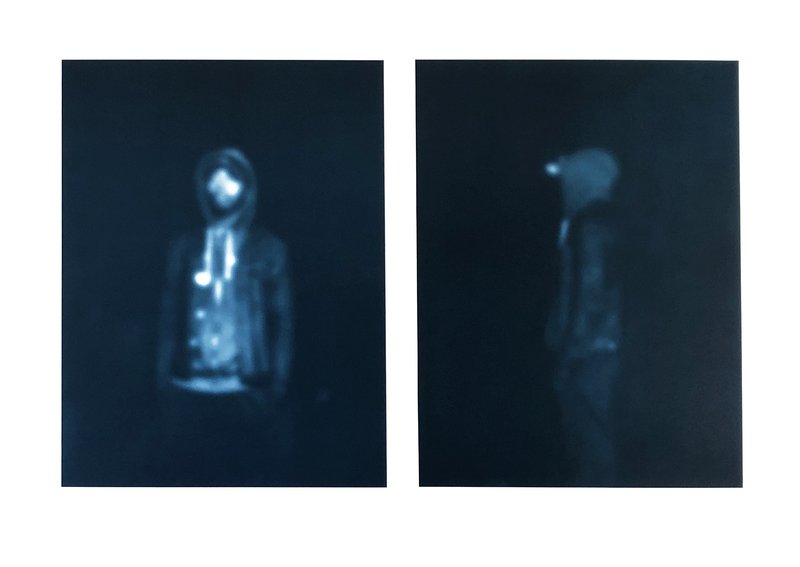

9818 (Glass House)

, 2009 - James Welling

9818 (Glass House)

, 2009 - James Welling

Many photographers have taken up Philip Johnson’s Glass House as a subject. Most of these works pay homage to the architect and his iconic design, but since I personally have misgivings about both I have found that approach too simplistic. I am most fond of James Welling’s interpretation of the house in which, over the course of two years, he placed different brightly-colored filters over his lens, filling the picture plane with swaths of red, yellow, green, and blue as if rendering a large abstract painting across the building façade. This formal exercise in transparency and reflection dialogs with Johnson’s own use of double entendre in his work, the connections between glass surfaces in house walls and camera lens being just one of them. I’m particularly drawn, however, to the way distortion alters our access to the building, how color occludes traditional interpretations of modern architecture. Welling was born in Connecticut just a couple years after the Glass House was built and I wonder to what degree memory influenced this series.

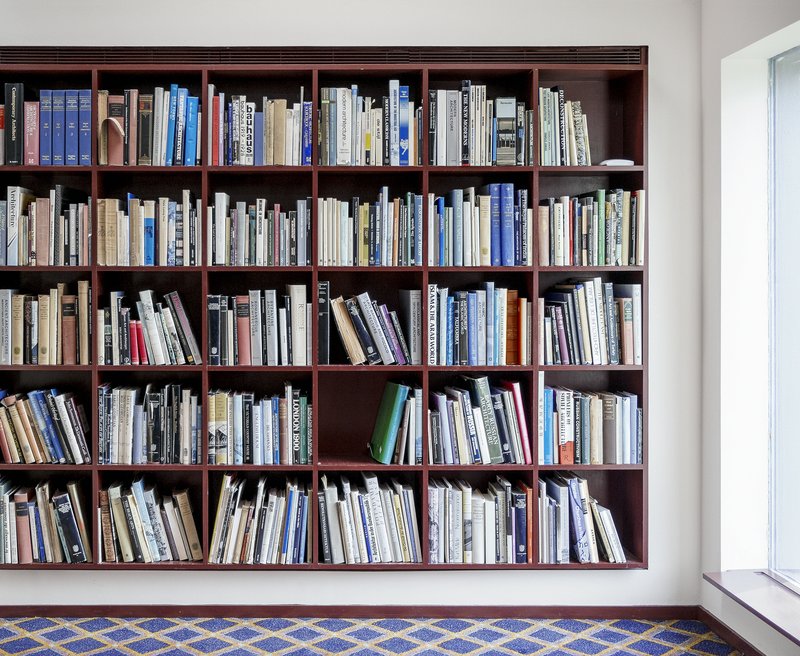

University Library, Hamburg

, - Candida Höfer

University Library, Hamburg

, - Candida Höfer

I have a weakness for environments photographed in one-point perspective, and Candida Höfer is a virtuoso at this approach. Objectivity and repetition render images that appear impersonal, an impression amplified by the grand theaters and libraries devoid of people she chooses as subject matter. The images, however, are anything but straightforward. You need to spend time with one of Höfer’s photographs, only then will the subtlety of pattern, play of light, the haunting traces of people, and the weight of history permeating the spaces reveal themselves. She is also a technical genius, so seeing her photographs in person can evoke, for me, the same feeling I get when standing in front of a painting by an Old Master.

Emily Bills - author of Wayne Thom: Photographing the Late Modern - published by Monacelli Press

Emily Bills - author of Wayne Thom: Photographing the Late Modern - published by Monacelli Press

To read more from Emily Bills, order a copy of Wayne Thom: Photographing the Late Modern here. And a copy of Emily Bills's California Captured: Mid-Century Modern Architecture Marvin Rand , here. You can get a monograph on the work of Catherine Opie here , one on Agnes Martin here and a great visual biography of the archtiect Philip Johnson here . And if you want to learn a little more about Candida Höfer she's in Great Women Artists here .