“Red is the archetypal color, the first color humans mastered, fabricated, reproduced, and broke down into different shades, first in painting and later in dyeing. This has given it primacy over all other colors through the millennia."

So writes Michel Pastoureau is his scholarly study Red: The History of a Color, a work that spans human artistic production, from the Lascaux cave paintings to the canvases of Mark Rothko . The color red, of course, is richly resonant, connected as it is with love and passion, anger and danger, the heat of fire and the spilling of blood. It’s been used to pigment the robes of Catholic cardinals and the Phrygian bonnets of French revolutionaries, not to mention, more recently, Donald Trump’s MAGA cap.

It is also the color of many of history’s greatest sports teams, among them the Liverpool F.C. of the 1980s, the Chicago Bulls of the 1990s, and the Chinese Olympic ping pong squad in any given decade.

The roll-call of great works of art that prominently feature this color is unsurprisingly long, but its most heart-stopping entries surely include Diego Velasquez’s painting Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650), Eugène Delacroix’s canvas The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), and Henri Matisse ’s great sea of crimson pigment, L’Atelier Rouge (1911). For this edition of Group Show, we compare and contrast six works by contemporary artists that put everything on red, and in the process speak of consuming flames and consuming desire, the perfection of nature and the imperfections of politics, the love in our hearts and the blood in our veins. Looking at their pulse-quickening scarlets, crimsons and vermilions, all other colors can seem, well, a little anemic.

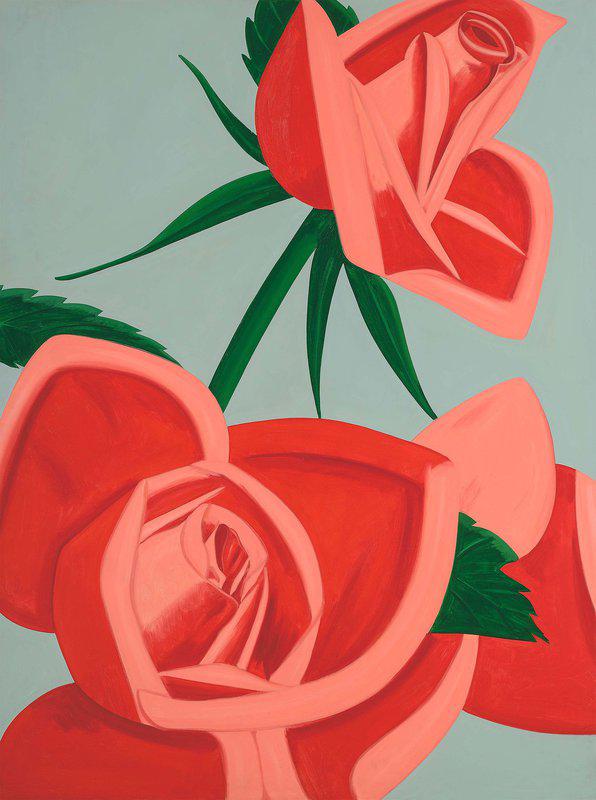

Since at least Greek antiquity, when its blossoms were closely associated with the goddess Aphrodite, the red rose has functioned as a symbol of (sexual) love. The reasons for this are not hard to understand: while the flower’s soft, incarnadine petals recall the inviting lips of a mouth or a vulva, by contrast its thorns speak of the potential perils of romance. Perhaps more than any other bloom, it has been hymned by poets and artists, from Robert Burns (“O my luve’s like a red, red rose/ That’s newly sprung in June”) to Emily Dickinson (“Ah! Little rose, how easy / For such as thee to die!), from Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting Venus Verticordia (1868), in which the titular love deity is depicted surrounded by scarlet blossoms, to Pierre-August Renoir’s canvas Bouquet of Roses (1890-1900), in which a drift of fallen red petals appears to suggest the transience of romantic relationships.

The acclaimed American painter Alex Katz ’s print Rose Bud zooms in close to its subject matter, capturing the unfurling of two young, still perhaps uncut blooms. Their red and pink folds contrast dramatically with their dark green stems and leaves, and significantly there is not a single thorn in sight. What’s the reason for this absence? Katz has said that “Realist painting has to do with leaving out a lot of detail. I think my painting can be a little shocking in all that it leaves out. But what happens is that the mind fills in what’s missing”. It seems that it is down to the viewer – drawing on a lifetime of joys and sorrows – to provide their own sharp thorns.

General Idea - Nine Lives, 1992

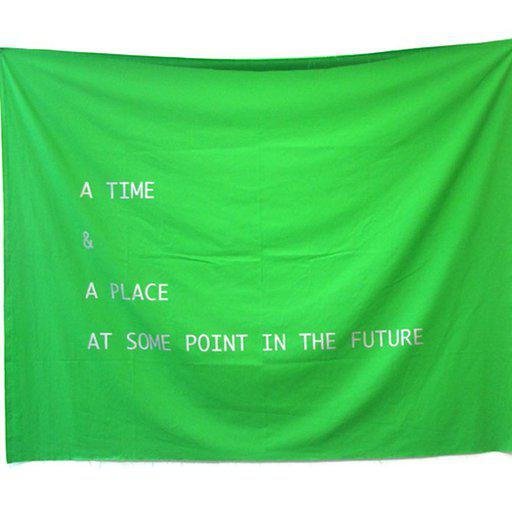

Reg flags are customarily used to alert us to potential hazards, whether that’s live fire on a shooting range, dangerous currents on a beach, or a high-priority email from an unforgiving boss. In their work Nine Lives, the pioneering Canadian artist trio General Idea (comprised of AA Bronson, and the late Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal, who both died of AIDS-related illnesses in 1994) present a scarlet banner, which bears the image of three stylized skulls. At first glance, its message seems clear enough: a warning not only of danger, but of death.

And yet, there is much to unpack in this seemingly simple image. General Idea’s flag evokes elements of several others, among them the skull motif of the piratical jolly roger, the red, white and black color scheme of the Nazi ensign, and a host of socialist banners – as fellow travelers are fond of singing, “the people’s flag is deepest red / it shrouded oft our martyred dead”. Then there’s the possibility that it functions as a kind of macabre group self-portrait (a poignant prospect, given that it was made only two years before Partz’s and Zontal’s deaths), and the fact that the skulls’ eyes resemble the “c” of the copyright.symbol. If most flags employ graphic clarity to mask a set of (political) contradictions, then General Idea’s Nine Lives runs its mixed messages up the pole, and lets them fly.

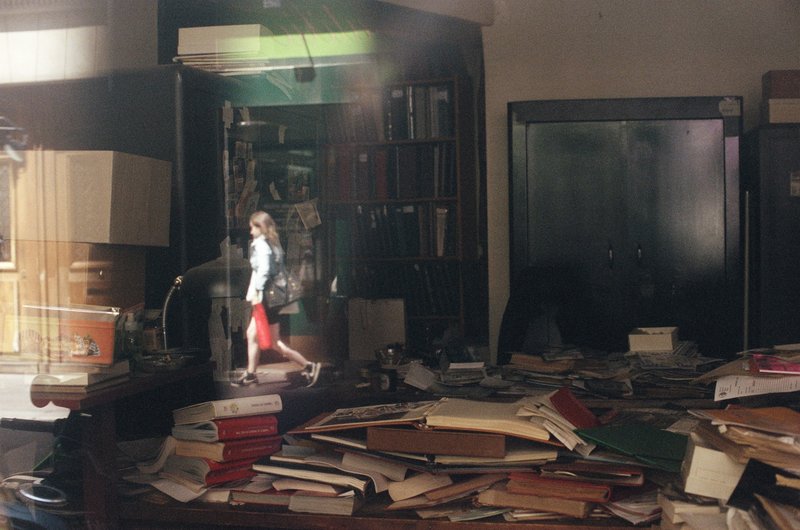

What connects the English landscape painter John Constable’s celebrated canvas The Hay Wain (1821) and the Canadian photographer Moyra Davies ’ shot, which was taken almost 200 years later in 2014? Not much, on the face of things, until we notice how each work uses a tiny patch of scarlet (the saddles of Constable’s horses, Davey’s titular bag) to make the whole composition come thrillingly alive. Perhaps more than any other, a mere drop of this color can have a serious visual impact. As Shakespeare’s Macbeth put it, following his murder of King Duncan: “Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood / Clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather / The multitudinous seas incarnadine / Making the green one red”.

There is something spectral about the young woman in this photograph – indeed, her red bag recalls the red coat of the ghostly, childlike, and eventually murderous figure that haunts the grieving parents in Nicolas Roeg’s classic of occult cinema, Don’t Look Now (1973). Look closely at Davey’s image, and we realize that her female subject is a reflection, and the space she is walking through is not the book-strewn study that dominates the shot, but rather the street outside. We might think, here, about exteriors and interiors – about how permeable we are, and just how much red blood the “bags” of our bodies contain.

Wolfgang Tilmans - Red Adidas, 2007

In 2003, Tate Britain hosted a retrospective of the work of

Wolfgang Tillmans

, which the Turner Prize-winning photographer gave the title if one thing matters, everything matters. This in an apt description of Tillmans’ radical visual egalitarianism, which sees him photograph everything from planes to political protests, lovers to drying laundry, raging waterfalls to the eye-searing patterns on a plastic metro seat. By attending mindfully to the things that float across his vision, no matter how modest they might be, he transforms a world of empirical facts into a world filled with feeling, and often disarming beauty.

Red Adidas

is, as its title suggests, on one level a still-life of a pair of red men’s Adidas swimming trunks. On another, it contains what might be whole histories of desire and loss. Who does this tight, nylon garment belong to, and why is he no longer wearing it? It might have been removed for a bout of frantic lovemaking in a changing cubicle, or else left behind by a departed lover, whose absent penis is suggested by the white cord that loops phallically against the scarlet fabric. Perhaps it is lost property, mistakenly abandoned in a cursorily cleaned hotel room. If so, then the intimacy of this object, and Tillman’s image of it, is all the more striking. Whatever its provenance, it feels freighted with emotion: note how this item of sportswear – broad at the top and tapering towards the bottom – bears a marked resemblance to a red, Valentine’s Day heart.

Nan Goldin - Joan Crawford on Fire, Thanksgiving, New Jersey, 2005

“You are not required to set yourself on fire to keep other people warm”. So said the legendary screen siren Joan Crawford, star of such iconic movies as The Women (1939), Autumn Leaves (1956) and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). It’s a statement that speaks to both the actresses’ defiant spirit (in 1945, she won an Oscar for her bravura performance in Mildred Pierce, two years after being ignominiously dumped by MGM as “box office poison”), and to the darkest sides of her character (Crawford’s daughter Christina’s 1978 memoir Mommie Dearest painted her as an emotionally and physically abusive alcoholic, more concerned with fame than motherhood).

In this photograph by the seminal American photographer Nan Goldin , we see a TV screen playing a Crawford movie in the den of a New Jersey home, on a dark, Thanksgiving night. At first glance this is a cozy scene, made even cozier by the presence of an open hearth, which blazes redly in the background, and from our vantage point seems to have almost precisely the same dimensions as the humming TV. Our eyes flicker from Crawford to the flames, from the flames to Crawford, each of them a source of incandescent, dangerous energy. What kind of drama might play out in this home, on this most family-oriented of holidays? Perhaps the answer is in another saying by the actress: “Love is a fire, but whether it is going to warm your hearth or burn down your house you can never tell”.

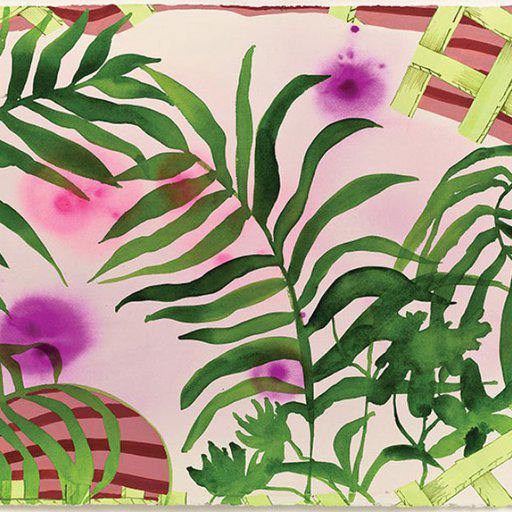

In the visual displays used in Western stock exchanges, red signals a declining price – a warning to careless investors that they’re in danger of losing their shirts. Not so in the Shanghai Exchange, where it indicates that a stock is in the ascendant, a nod to the widespread belief among the Chinese that red is an auspicious color. This derives from both the reverence accorded to the founder of the Han dynasty, Gaozu (known as “the son of the red Emperor”), and also to the myth of the nián shòu, a monster who was said to terrorize people and livestock each Chinese New Year, until it was discovered that this creature suffered erythrophobia, or fear of the color red, hence the crimson lanterns that are now hung from windows and doorways to celebrate this festival. Looking at Mary Heilmann ’s photograph Lucky , in which a pair of black dice tumble against a deep red backdrop, it might seem that when it comes to summoning good fortune, the acclaimed American artist is firmly with the Chinese.

What’s intriguing about Lucky is that it depicts not the result of a dice roll, but the moment when its result is still in doubt. Heilmann – whose many notable exhibitions include a 2007 retrospective at the prestigious New Museum, New York – does not tell us what game is being played, or for what stakes, or what might constitute a winning or losing throw. Does this even matter? Or is what she’s drawing our attention to those exhilarating seconds when the dice fall through the air – when both triumph and disaster have been taken out of our hands, and given over to a higher power, whether that’s blind chance, an interventionist God, or indeed the auspiciousness of a color that once caused the terrible nián shòu to turn tail and flee?