When a single work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art catches your attention and stops you in your tracks, it can feel like you’ve unearthed a hidden treasure. In Phaidon ’s upcoming book The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look at Art , over 100 artists reflect on this same experience—the moment when an artwork from the Met’s collection overwhelmed their senses, inspired their practice, or changed their view on art making in general. The next time you visit the Met, use the excerpt below as your tour guide, and allow these seven artists—John Baldessari, Eric Fischl, Ann Hamilton, Jeff Koons, Glenn Ligon, Catherine Opie, and Hank Willis Thomas—to lead the way to their most cherished works on view in the two-million-square-foot museum.

Philip Guston

's

Stationary Figure

On View in Gallery 915

Philip Guston,

Stationary Figure

, 1973

Philip Guston,

Stationary Figure

, 1973

I get labeled a conceptual artist, which I think is a misnomer, but everybody gets a label in life. I get labeled a California artist too, and I think that’s a misnomer also. I would rather just be called an artist.

I first became interested in Philip Guston when I was in high school. My parents subscribed to Life magazine, and his early works were in it. I would tear out those pages and save them. It was very sophisticated work. When he started doing this later work, he was severely criticized: it wasn’t art, and blah, blah, blah. And I thought, well, he’s on the right track if people are saying that about him.

What I like about Guston is that he is trying to deskill himself and take all the sophistication away—that he’s just like a really dumb artist. And I’m using dumb in a good way. So it’s this seemingly clumsy but very sophisticated brushwork. His works don’t have slick surfaces; you can see the brushwork.

I also like his simplicity of choice in subject matter. Like Van Gogh’s painting of a pair of old boots: you don’t need to paint a cathedral, you just have to be an interesting painter. It’s utter simplicity, those bug eyes. And where’s the nose? Have we ever seen a mouth? It’s almost like the eyebrow and the ear could be interchanged. And his figures are always smoking a cigarette. There’s always that dumb cloud of smoke, which if it weren’t for the cigarette, could be a rock, could be anything! Don’t you laugh when you see that?

It’s macabre humor. It’s a laugh that’s also shadowed by the thought of the brevity of life. A poetic mind would think that death is absurd and funny. There are elements of time: the light and the clock and the short duration of the cigarette. There’s more light inside the room where he is than there is outside. It’s like a prison cell. He’s almost in bondage with the bedclothes—you might even call it a straitjacket. It’s nightmarish, in some ways—being constrained and trapped by time.

The painting’s tough to like. I think the average viewer is going to say, “Yeah, my kid can do that.” And that would be dismissive. I think it’s brilliant: making art look like it’s not about skill. He knew he was going to ruffle feathers and irritate people. I absolutely identify with his courage in doing that. It’s one of the things I’ve always emphasized: don’t be a virtuoso, and don’t be a show-off.

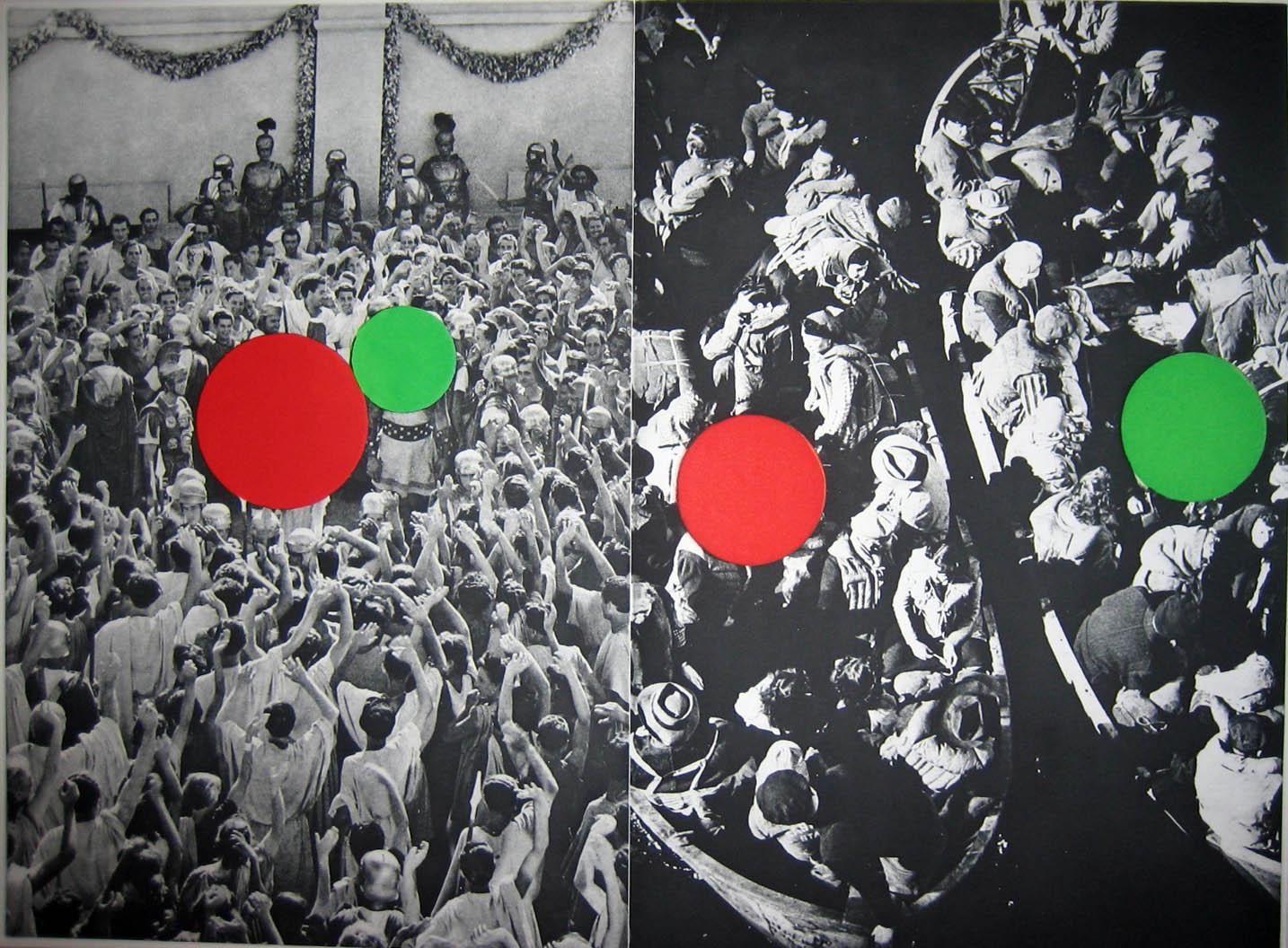

Max Beckmann's

Beginning

On View in Gallery 901

Max Beckmann,

Beginning

, 1949

Max Beckmann,

Beginning

, 1949

People distrust that they can actually read a painting. It seems like you have to know a lot about what’s outside of the painting in order to understand why you’re even looking at it. The great thing about Max Beckmann’s paintings is that no single reading of them is actually right. They contain narratives that are based on deeply personal associations, coupled with mythologies you may not actually need to know to enjoy the work—but they just add layers and layers once you do.

I feel very close to the general narrative of Beginning : a boy coming of age. In the central panel, Beckmann presents a boy dressed like a prince on his hobbyhorse, which is very animated. During puberty, boys destroy their toys: Puss in Boots hanging helplessly immediately sets that in motion.

The painting on the right is of an elementary school. It’s all male, and some of them are behaving badly. In showing you the picture, Beckmann implicates you as a disciplinarian or as a participant, making you remember when you did this. There’s an old man, who seems to be the teacher, and behind him is what appears to be a mature male figure but is only a bust. Then there is a globe that also is like a ball, and it looks like it’s going to land and pop. He makes it very precarious.

In the panel on the left, the boy is looking out at what he is going to enter or possess. He jumps over everything between youth and death. It’s almost a dreamlike transformation. Beckmann’s sense of hierarchy comes from emotional necessity. You can see him really weighing how to describe something.

Eric Fischl's

Two From Behind

is available on Artspace for $2,000 or as low as $176/month

Eric Fischl's

Two From Behind

is available on Artspace for $2,000 or as low as $176/month

A part of a ritual in society is that you collectively recognize the momentousness of it, and you share it. You go through puberty, and it begins to call up the nature of desire, objectification, the currency of exchange. It makes me feel like I’m not the only one.

Nobody can compete with the complexity of Beckmann’s works. He’s both constructing and watching something fall apart simultaneously, and yet he stays very close to the human drama. He’s painting about the struggle of being human.

Bamana Marionette

On View in Gallery 350

Marionette: Male Figure (Merekun), 19th-20th Century

Marionette: Male Figure (Merekun), 19th-20th Century

For me, the act of making is also an act of finding something, and you hope that you can set up the conditions to find what you need. The museum sets up the conditions for associative, meandering thinking. Different objects draw me in, and this is one that I’ve returned to again and again. This is a puppet, or marionette. It has all these traces of having been used: the fabric is stained, it’s worn in places. It had a life in the world, but now it’s completely removed from that life.

There’s this whole “body empathy”—there’s an address from the object to me as a viewer. We recognize the figure with the most minimal of information. The red hands—they’re wooden and they don’t have a lot of gesture in them, but they hold the possibility of becoming any gesture. And then there’s the magic of the hands that actually manipulated it.

You have to imagine the marionette actually moving. Imagine the very rigid stoicism of the face or the head, which seems helmeted and regal. Then imagine this cloth and how it moves, and how this puppet could become something that just glides across or commands a presence in a story.

The modesty of it gives it more potential. It is made of the most ordinary materials: string, cloth that’s falling apart, pigment, a little bit of wood and metal. Out of those common materials is this animate presence.

Ann Hamilton's Mirrim is available on Artspace for $2,500 or as low as $220/month

Ann Hamilton's Mirrim is available on Artspace for $2,500 or as low as $220/month

I would love to be able to make this, but I can’t in my culture. This marionette connects me to a place and culture where the artist has a role of telling stories. It originally had a function in a world outside the museum, but many, many contemporary artworks assume the space of the museum, whether or not they ever get inside one. This is obviously an object that was made to be animated but is now mute, and it’s now possible for me to animate it in another way.

How do you take the things that you love, that you are drawn to, and approach what they do? You have to go in through a side door. What is it that makes this alive? You could think about this as an object that’s emblematic of the role of the artist. Maybe our task is to animate, much like a puppeteer. You can address things through a puppet that perhaps you can’t approach face-to-face: contemporary politics and social issues, for example. Then you can bring that lens back to your own process.

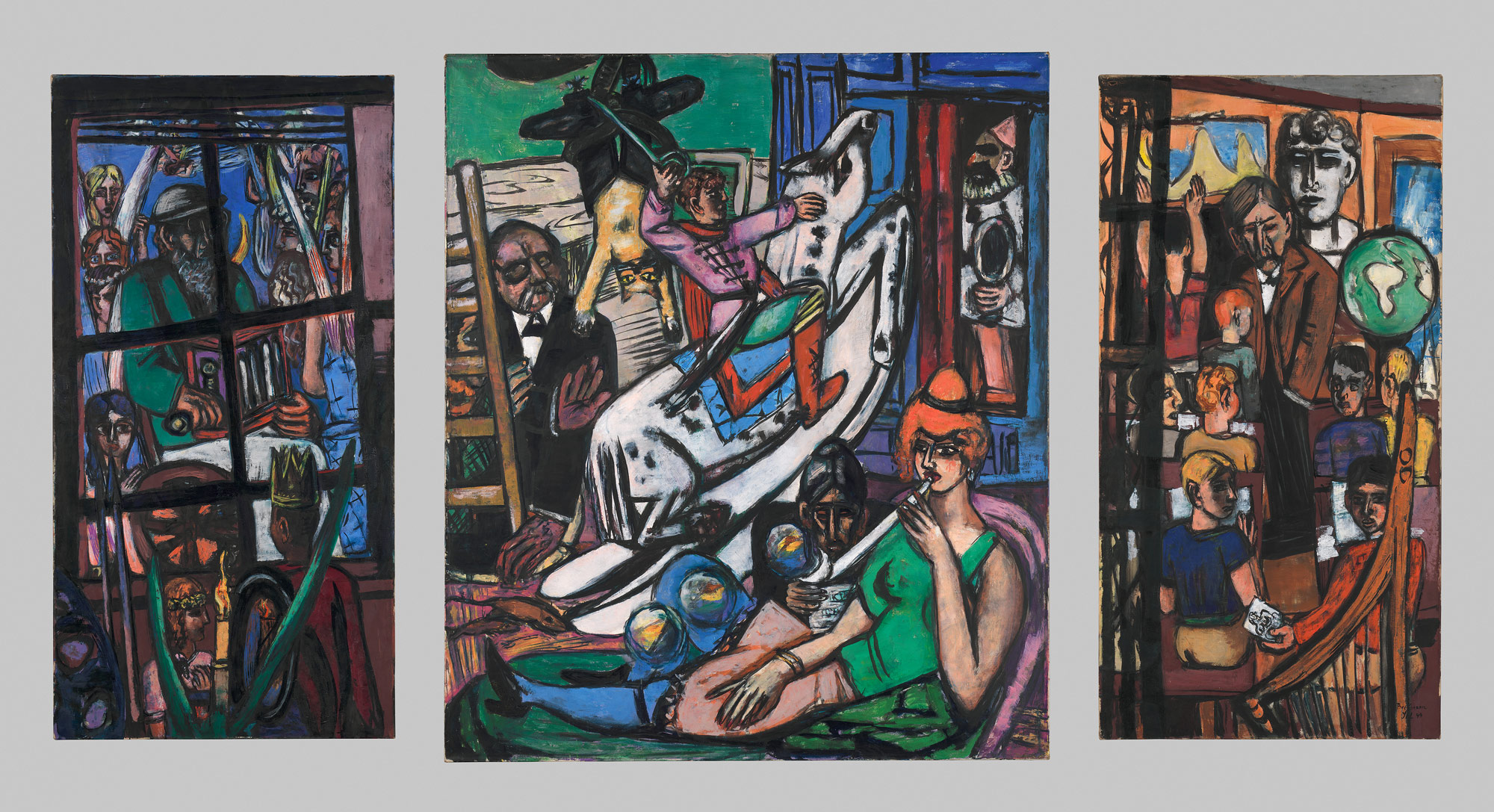

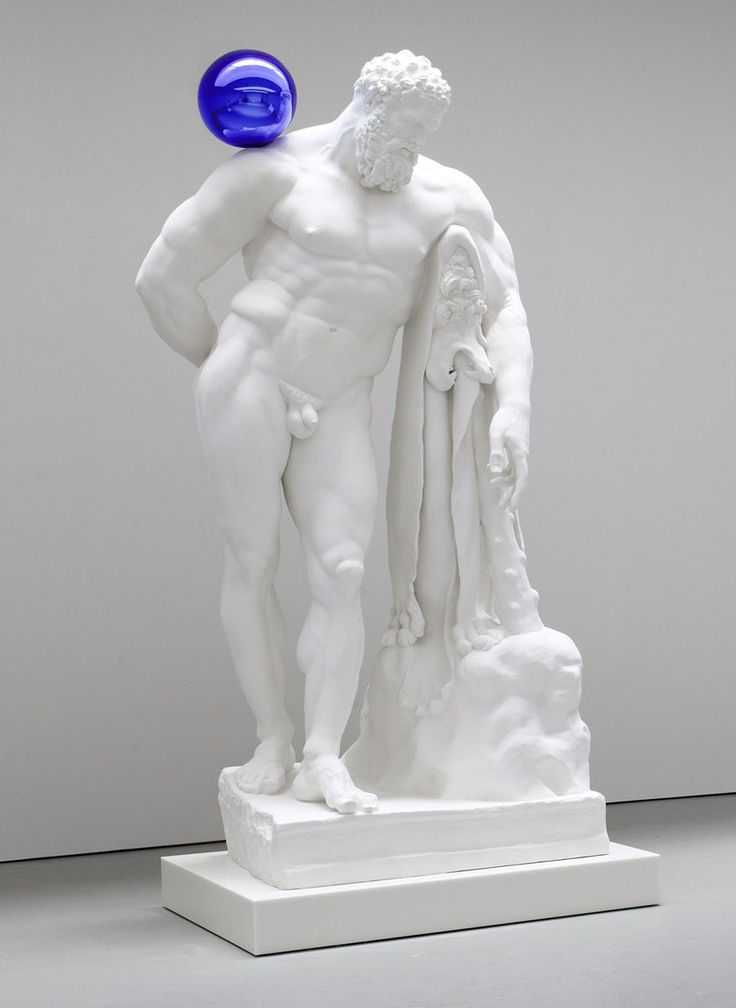

Roman Sculpture

On View in Gallery 162

Marble Statue of a Youthful Hercules

, AD 69-96

Marble Statue of a Youthful Hercules

, AD 69-96

I love the ancient Roman time period when people were creating things that competed with nature and that were above Man himself. In the Roman Sculpture Court at The Met, a sense of the eternal is conveyed both through the biological and through ideas. A lot of the sculptures are Roman copies of Greek originals, and you can feel the dedication that the Romans had to preserving all of the power within the original Greek pieces from third century BC. At the same time, there was always the desire to create a new form, a new material realization.

Through the senses you develop ideas, and so you go from the richness of physical biology to the abstraction of pure ideas. Every intention was realized with just the movement of the flesh, a detail of the eye, the length of a toe, the shaping of a breast, or the way the hair moves. All of these different characteristics, from one statue to another, inform you of who they were—whether it’s Hercules or Aphrodite. All of this information was placed within the work of art.

Jeff Koons,

Gazing Ball (Farnese Hercules)

, 2013

Jeff Koons,

Gazing Ball (Farnese Hercules)

, 2013

The little details in Roman sculpture can be so awakening. The bodies are vehicles for a dialogue about life, about fertility, about procreation. Desire and beauty are very important within art to make the body sensual. Yet when I look at the statue of the Three Graces , I don’t feel that it is necessarily about desire or dominance. Maybe it’s because there are three of them. The work is more about one’s place within the community.

The Roman sculptures represent, to me, the most vital information we need as human beings to live our lives to the fullest. Humans become larger than life in these sculptures. The gods depicted embody big ideas, and you can feel within your own body what it’s like to be Hercules when you look at them. I love that drive and fantasy to be everything that we can be as individuals and as a society. It’s so stimulating, and it enlarges the parameters of what our lives can be. I want my life to be as vast as their perception of what life could be.

The Great Bieri

On View in Gallery 352

Reliquary Element: Head (The Great Bieri), 19th Century

Reliquary Element: Head (The Great Bieri), 19th Century

Much of my work is painting. It’s hung on a wall; you look at it. I don’t make sculpture, so the problems of sculpture are foreign and surprising to me, and I have to learn them. From African art, I’m learning how things operate in space.

It always amazes me that these bieri figures are carved out of one piece of wood. What’s interesting about this head is that it’s quite stylized in terms of the features: the enormous eyes, the arch of the eyebrows, the mouth, the nose. They’re general signs for a face, but they are also very specific. This isn’t a portrait in a direct sense, but it’s a representation of what you want someone to do. For instance, the ears stick out, creating a conduit to the ancestors. The object speaks, but you also speak to it. The placement of the ears is about its receptiveness to one’s prayers. The object speaks, but you also speak to it. I love the idea that something so abstract can be so specific.

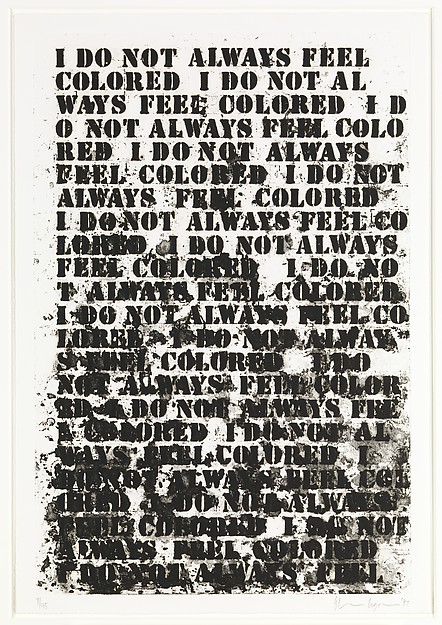

Glenn Ligon,

Untitled: Four Etchings

, 1992

Glenn Ligon,

Untitled: Four Etchings

, 1992

Any work of art is an idealized representation. It’s an idea about something; it’s not the thing itself. Even though this figure doesn’t fall under the heading of art with a capital A or sculpture with a capital S within its original community, it’s beautifully proportioned. The oval shape of the head, the long straight neck—its aesthetic value enhances its spiritual value. It’s a human trait: we worship beautiful things. It’s part of what keeps us going back to these objects.

I don’t approach my work with the idea of making a beautiful object, but beauty is often what hooks people into the other issues in the work. We’re very interested now, in contemporary art, with what a viewer’s experience is, a viewer participating in a work of art. For me, these objects have already done that. The relationship that people had to these objects was about activation. People didn’t just stand there and look at them; they did things with them.

This sculpture was made to sit on top of a container for relics, so it has generations of engagement. At some point, though, the religious significance of the object dissipates, and it ends up in a gallery space. Museums often have objects that they want to conserve and not change, but these objects do change. You see the palm oil coming out of it from the libations that have been poured on it, and the palm oil is a subtle reminder that it once operated in a different system. Even though these objects are now in display cases, they’re not fixed. Their meaning changes over time.

Louis XIV's Bedroom

On View in Gallery 531

Bed Valances and Side Curtains, circa 1700

Bed Valances and Side Curtains, circa 1700

I grew up in Ohio, and I faced a cornfield across the street—that was my everyday life as a young kid. When I was nine years old, I read a book by E. L. Konigsburg called The Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler , and in the book the main character, Claudia, runs away from home to The Met. Being this kid in the Midwest, what caught my attention was this idea that there was a place of imagination that you could explore. I was watching a school group of young kids today walk through Louis XIV’s bedroom, and even though the teacher was telling them to line up, you could tell that they just wanted to experience the room as it was to be lived in.

It’s a staged space. The room is not just a bedroom, it’s also a portrait. It’s a portrait of multiple histories in relation to Louis XIV. This room tells a story about that period of time, with this opulence and wealth, and notions of what is valuable or what needs to be seen. For example, in one part of the room, incredible wine-pouring vessels depict mythological scenes, with serpents and a beheading.

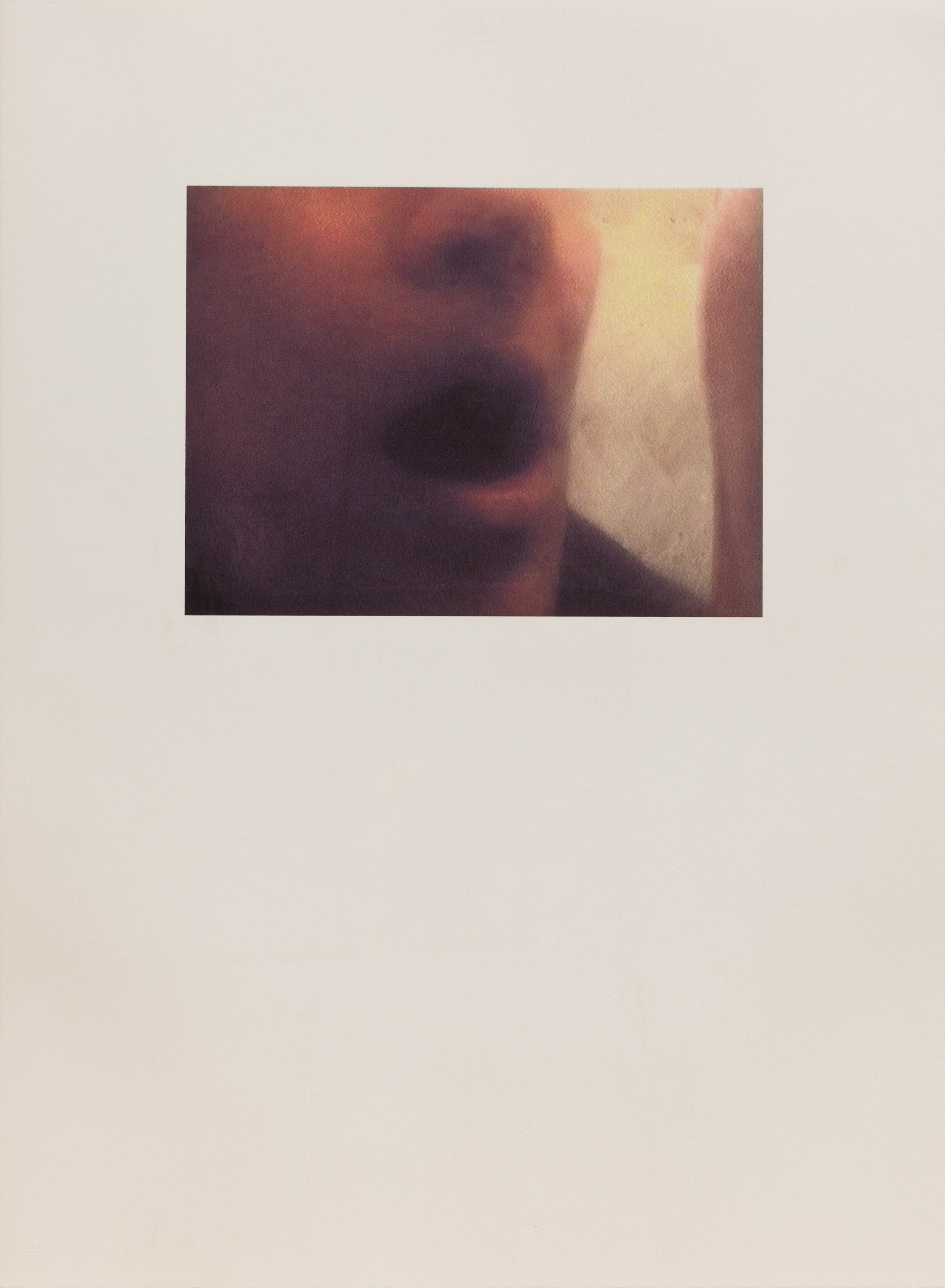

Catherine Opie,

Self-portrait/Nursing

, 2004

Catherine Opie,

Self-portrait/Nursing

, 2004

Think of the privilege one had in owning these objects, which took a really long time to make. Things are gilded, they’re inlaid, they have craft in them. Craft is a bad word in the art world right now—you don’t want to talk about craft. I actually value that I have really tried to master my medium. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have always had a voice within my work, and I long for this time period because of the slowness of the handmade. Even though I make photographs and the hand isn’t necessarily apparent in photography in the same way that it is in sculpture, painting, or other mediums, it’s in what I choose to look at and how I frame it. Much like this room, the specific moment you decide to describe in a photograph is also a kind of a stage.

I treat these kinds of spaces as if I’m making photographs. I can look at paintings and objects thoroughly and with imagination, and I think that’s because I read The Mixed-Up Files so many times as a kid. Unfortunately, that’s how I also experience most of the world, which can be a problem. My partner’s constantly telling me not to stare, to just experience. And I respond, “I am! I’m experiencing by seeing.”

Daguerreotype Button

On View in Gallery 850

Button, 1840s-50s

Button, 1840s-50s

As an artist, I’m interested in trying to bring things we’ve packed away back out for discussion. I’m fascinated with how our history and our understanding of the world shifts, so I think of history as a moving target.

This is a daguerreotype button, and there were long-standing questions about whether or not it was an abolitionist pin because there appears to be a “white” hand and a “black” hand holding a Bible. We now believe that the two hands belong to one person, and we’re unsure as to whether or not they’re holding a Bible. That’s really fascinating to me because I made a replica inspired by the original definition.

When a person wears a button, they’re essentially wearing a question that they want to activate in others, but you’d have to be so close to them to even really see what it shows. To create a level of detail this small really speaks to the daguerreotype medium, which is a nineteenth-century process that involves coating a piece of metal with emulsion. When you look at it, you’re looking at both the reflective metal and the image, which can seem to disappear before your eyes, depending on the angle of light and where you’re holding it.

These look like young-adult hands—maybe someone who did manual labor for a living. I think the cropping is intentional because the subject becomes anonymous; the hands become symbolic. The way in which they’re clasping the book is really about intimacy and protection and coveting the subject. The photographer also wanted us to know that this person reads and was engaged intellectually. Many photographs that were taken of African-Americans during that era feature them holding books to contradict the myth that “black” people were inferior.

Hank Willis Thomas,

Thencefoward and Forever Free

, 2012

Hank Willis Thomas,

Thencefoward and Forever Free

, 2012

Today people wear pins and buttons to align themselves with political movements; I am really excited that these are long-held traditions. The fact that we don’t know if it is a “black” person’s hand or a “white” person’s hand, or what happened to those hands later, is great because that means they’re our hands. There is that magic of visibility/invisibility and meaning, and that ambiguity is what makes most art both legible and eternal.