Chances are that in the past year or two in particular, you've come across the following phrase while scrolling through your social media feed: "Abuse of power comes as no surprise." This endlessly quotable line is but one of artist Jenny Holzer's hundreds of "truisms" she's been developing since 1977. Disseminating these truisms by public means (earliest iterations included fliers; later, LED screens), Holzer is among one of the most well-known and iconic artists working today, and in 1990 was the first woman artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale where she won the prestigious Leon d'oro award—the grand prize for best pavilion.

Though Holzer is now an internationally recognized figure in the art world, the artist sprang from humble beginnings. In this refreshingly candid interview with curator Joan Simon, excerpted from Phaidon's 1998 monograph, the artist recounts her childhood in Ohio, explains some of the first artworks she ever made in art school, and describes the moment she realized she was "useless for normal life" and decided to become an artist.

Let's go back to the beginning. Where were you born, when and to whom?

Gallipolis, Ohio, 1950. In Holzer Hospital, to Richard and Virginia Holzer.

Holzer Hospital?

My grandfather and grandmother founded it. He was a doctor and she a nurse. There were no hospitals in that area so they made one.

When you were a child, what was Ohio like?

I thought it was pretty grand. We lived in a new development on the edge of a town of 30,000 people. It had been an apple orchard, a wild abandoned apple orchard. I stayed until I was sixteen, and then went to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to improve my image. I wanted to see if I could be less of a nerd.

Why did you think you were a nerd?

Inner conviction. Tall. Too skinny. Approximately intelligent. Things like that.

Did you do any art when you were a kid?

I did most of my art when I was a kid. I wish I still had the same rhythm and frequency. I drew.

Which you don’t do any more?

No. It went away. And I’m sorry.

What did you draw?

Epics. No single-sheet stuff after I was five or six. Shelf-paper scrolls. Everything from Noah’s ark up to the development of the automobile. I tried to get it all down.

Was anyone in the family and artist?

My grandmother’s sister, Audrey Donaldson Ruston, who did Grandma Moses-type paintings. Even better than an artist, she was a psychic. She could predict events and could find water with willow switches. The art and water-witching were a great combination.

Did you go to museums as a youngster?

I went to the Metropolitan in New York once, for an hour.

Do you remember anything in particular from that visit?

Rembrandt behind a rope. They had just bought one, and had it out. I think they even had the price by it. About a million dollars. It was something like what my father used to do to sell Fords.

Your work is so much about “public voice,” I’m curious to know if you remember any influential ministers, teachers, lawyers, politicians, newscasters? American newscasters and radio announcers often come from the Midwest.

This probably sounds fake, but I did like that Times Square sign that had war news on it, that I’d seen in old news reels rebroadcast on TV in Ohio. It had reports from the front.

The one I remember from my childhood had only words. Was there another sign with moving pictures?

My “dream sign” of childhood was the text-only Times Square “zipper.”

That news “zipper” has been in operation since 1928. In fact, it is the same Times Square building where you, in 1982, first worked with electronic signs on its Spectacolor board.

What did you intend to study in college?

I was trying to be normal, so I thought maybe I should be a lawyer. I wound up at Duke University in North Carolina on the suggestion of an alcoholic guidance counsellor. I was too timid to go where I wanted. That was Radcliffe. I had the notion there were interesting women there. I wanted to see what smart women did. At Duke the women were bright, but they didn’t always let on.

After studying liberal arts at Duke from 1968 to 1970, you changed school a couple of times. Why did you transfer to the University of Chicago?

I was in love. He was going to graduate from Duke and I wasn’t all that happy there. I felt becalmed but not enchanted. I wanted to go to a new place, a city. I was getting closer to admitting that I was, well, two things: useless for regular life and less ashamed about wanting to be an artist. I thought I could do art in Chicago.

Chicago was the best place I’d ever been. I loved the University and the city. It was very hard to leave. I would have stayed, but as a transfer student I would have had to study still more liberal arts. If I wanted to do studio, I couldn’t remain. While there, I did manage a fair amount of print-making and a lot of drawing. I was happy to use my hands.

Why did you choose Ohio University in Athens?

It was the time of the Vietnam War. My boyfriend, a conscientious objector, found a job at Holzer Hospital. See how we circle back? I wanted to concentrate on a studio, and, from my summer school experiences, I knew there were a number of good people teaching at Ohio University. That was sufficient encouragement.

When you graduated from Ohio University in 1972 with a degree in fine arts, did you want to keep doing art?

I wanted to, but I couldn’t figure out how. In my childhood, the artist I knew most about was Picasso. I saw him in a magazine article with photos in which he was on the beach ogling a mistress. I knew I wasn’t Picasso. I didn’t know how to be an artist.

What was your work like at this point?

Things that were found. Data. I had worked at Holzer Hospital in the claims department. I typed cards with information about what patients were suffering. For my artwork, I used all the cards ruined by my typos. I pasted the cards on a panel, in rows. I put them in lines, just had to organize them in tight, neat rows. I didn’t show the piece to anybody.

What did you do after graduation?

I went to Europe: Germany, France, Spain, Denmark; to Frankfurt, to Paris, to Madrid, to Barcelona. I saw many major museums for the first time. I looked at medieval and Renaissance art. The Goyas in the Prado sent me—his darkness and determination to look and show perfectly.

And after the European stay?

I went home for a while. I tried to go back into the horse business. I made a run at it a couple of times. I gave riding lessons, worked at farms, galloped youngsters and walked hots. Not my talent.

The horse business was your mother’s work.

She was a riding teacher. I was no good at it. I gave up on horses, went to Arlington, Virginia, got a job at People’s Drugstore, and wasn’t discovered. I started making some paintings, and I decided to go to Rhode Island School of Design for summer classes.

You actually went to Rhode Island School of Design two different times. Was this the 1974 summer session when you took the “painting alternatives” class?

Yes, that’s the summer class.

Some of the works you made that summer were the first of your public pieces.

I did paintings I didn’t like. I was cutting them into ribbons and ripping them. After I had done that to a huge painting, I had all these painting shreds. I thought maybe I’d tie them up, tie them together. I started doing that and made a half mile-long painting. It was a really big bad painting, enormously labor-intensive, painted on both sides. I left it at the beach. I watched people walk by it and on it. Be around it and ignore it.

What was the bread piece, Pigeon Lines (1975)?

Longing for order, I put bread out in geometric patterns. The pigeons had to eat in squares and triangles—sometimes they had to eat in lines.

And the indoor environment, the Blue Room (1975)?

That was one of the first pieces I did that felt right. Everything in the room was painted. The walls, floors and ceiling, the glass in the window, the door, were all done white. Then I went back and put on a Thalo blue wash over the whole room. Where the paint would dry, all of the surface would have an irregular edge. The space was disorienting. The paint was rather lovely, especially that color. I did the room instead of easel painting and presented it to the faculty and the students. I worked outside for the general public but didn’t have the idea of inviting them inside. I was also working on plain painting then.

What were those paintings?

I made abstract paintings that were fairly traditional. The only somewhat unusual thing I did was to paint pieces of canvas and then superimpose them. The result was traditional abstract painting with literally overlapped fields. Then there were long, rectangular, found fabrics on which I began to write.

What did you write?

This is a bit embarrassing, but one dark to light green material made me think of the depths of the ocean, so I wrote oceanographic information. That was lame, and it sent me to the Brown Library to find more subject matter: a return to the library. Next I did a blue fabric piece with text about time and space, and I began to draw the diagrams.

Maybe this started with seeing the old boyfriend’s physics diagrams. I thought they were great. I loved drawings of time. I also saw that trying to represent time was kind of absurd, kind of grand.

You re-drew the diagrams you found in the library?

Very carefully, and painfully, on paper. Hundreds of drawings. I would only try once. I had to draw perfectly on the first time, and if I couldn’t, I’d stop and start a new one. It was a horrible test. I tried to draw the diagrams free-hand just as they are in the books. Ridiculous. Straight lines. Hatch marks.

How were these discrete pieces of information organized?

I made books and I stacked the drawings in boxes. Sometimes they were grouped by subject.

What did making an extremely precise copy of someone else’s original (even one already mechanically reproduced in a book) mean for you? Contemporaries of yours, such as Sherrie Levine, made this a critical practice.

It was a trial for me, a salute to the subjects and a study of representation. Eventually it was a fascination with the captions.

After summer school you stayed in Rhode Island.

I met Mike (Glier) in the RISD “painting alternatives” class, and after summer school, I found a studio in Providence. I decided, OK, I’m going to be an artist. A year later I went to graduate school there (1975-77). Before I went to graduate school, I worked as a model for RISD drawing and sculpture classes. Then I entered the painting program.

Put your clothes back on.

Put my clothes back on as a graduate student and taught some of the same kids for whom I’d modelled. That was a manoeuvre. In the studio I was working hard. Some of the faculty rejected what I did. They hated my blue room and my videos.

What were the videos like?

Not great and somewhat autobiographical. Once, I went to my grandparents’ house and shot all around their farm. That’s as close to autobiography as I ever came. I couldn’t manage it.

What other art were you connecting with at this point?

When I was working in summer school, Bruce Helander said the pieces looked like Nancy Graves’. By the time I got to graduate school, I ran into John Miller, who was interested in the art journal The Fox. He educated me.

How did you get from RISD, where you got your Masters of Fine Arts degree in painting in 1977, to the next stop, New York?

Mike had been accepted into the Whitney Independent Study program, and I was desperate not to get tossed from RISD even though I didn’t want to be there. Actually, it was better than that. I wanted to go to New York City to be an artist. I was in trouble with the RISD painting faculty. One of my videos was about alcoholism, which was in my family, and in the faculty. Someone asked me, “You would expose your alcoholic aunt?”, and a painting professor said, “You would do anything. That is what is wrong with the twentieth century.” I considered suicide.

The alternative became New York.

I applied to the Whitney program, and was accepted.

That was in 1977. What’s discussed most often regarding your time at the Whitney program is the reading list which, you’ve often said, was a prompt to your writing Truisms. Who assigned this list, and what import did it carry in the program?

It was Ron Clark’s list, and it was important.

Did the program focus more on theory than studio issues?

There was a dose of theory, and they were quite willing and able to discuss studio. I thought the program was nicely balanced. They were hands-on when needed, hands-off when it was crucial. I liked that.

What artists were important to you at the time?

Yvonne Rainer fascinated me. I thought about the things she had done with the body and with words. They scared me to death but I wanted to find a way to her subjects. I couldn’t see how. The way became clearer, and it had to do with language.

What was Rainer like as a teacher?

A bit remote. Reserved, in a dignified, elegant for of way. I appreciated her even if I mostly observed her. I didn’t talk to many people in those days.

The first work of Rainer’s you had seen in person was the film Kristina Talking Pictures (1976).

The first things of Rainer’s that struck me were the pictures of her performing at Judson. I was amazed that she could be in motion with clothes off, being expressive in that way. I didn’t fully understand Kristina Talking Pictures, but what was clear—and I really can’t explain this—is that the piece was hers. That she made it. It was the story of a woman.

The Story of a Woman Who…, as another of her titles puts it.

Exactly. A woman working. Going back to the Picasso problem. Here was a woman’s life, and she was deadly serious.

Any other artists?

By the time I was part-way through undergraduate school, my art history went to Rauschenberg. I had a whiff of Joseph Kosuth by the time I was out of RISD. By the Whitney I was, maybe not up to speed, but something approaching that. Vito Acconci, Dan Graham and Alice Neel all talked at the Whitney.

When did you begin to write your texts down?

Sometime in the first session of the Whitney program I tossed the painting with captions and started writing. Then I had to decide what to do with the writing.

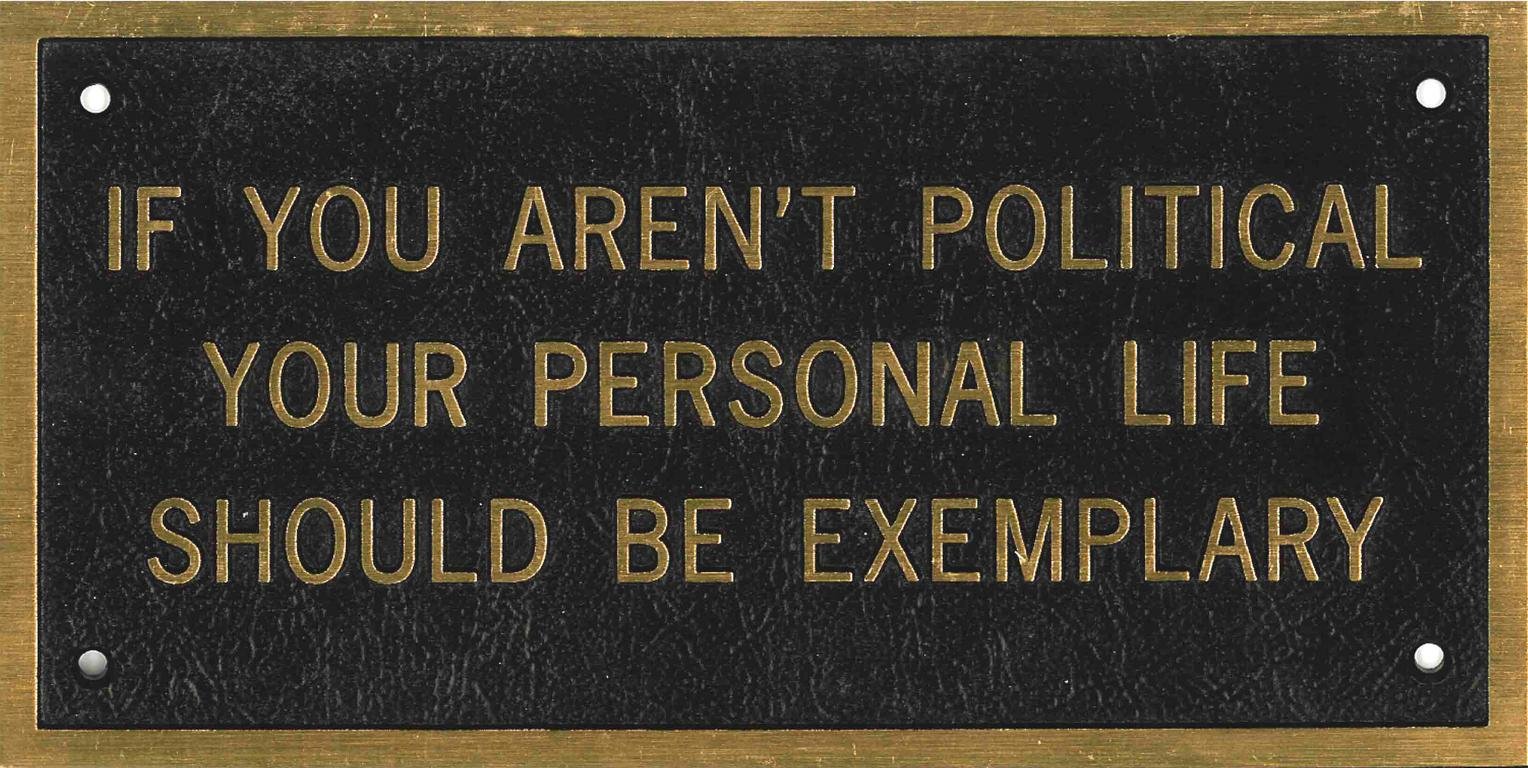

Why did you write the first Truisms?

It’s too neat to say it was just the Whitney reading list, but it was influential. I was intimidated by the list but wanted to address the subjects. I did the best I could with a number of one-liners.

Did everyone in the class address the list?

Some people even read it (laughter). I read Sontag, and it was the first time I understood something of the difference between the critic and the artist. The distinction between writing about something and just plain writing. I didn’t read much of the French stuff. Couldn’t appreciate it. I read some of the Marxist offerings.

…

How did you decide what form the Truisms should take?

I was still at the Whitney when I did the first poster. I hate to give Mike all this credit, but he had the idea of doing a street poster. I was jealous immediately. The fact that he was going to do a poster was enough to make me print one.

What was to be printed on Mike’s poster-to-be?

A man falling through space.

What was your first poster?

Thirty or forty of the best Truisms. I didn’t alphabetize them—that change happened later. I typed, offset and pasted them on walls around town.

Then what?

I just kept going. I didn’t dare think of the reaction to them, but I hoped they would mean something to someone. At that stage I wanted to stay in motion, like tying the knots of the painting of a thousand cuts. I had to work and write a lot.

You finally did.

A couple hundred.