More than half of all British citizens just voted to sever their ties with the European Union, a decision made in no small part due to a boiling-over fear of foreign immigration and refugees. At the same time that these historic votes were being counted, award-winning British filmmaker John Akomfrah opened a show of new work in Lisson Gallery’s new Chelsea space in Manhattan. Billed as his “first major exhibition in the United States,” it serves as his introduction to an American audience. Given Akomfrah’s career as a keen observer of racism and migration, the unfortunately apt timing also gives his show the sense of being ripped from the latest headlines.

While still gaining visibly internationally, Akomfrah, who was born in Ghana and raised in the U.K. since the age of four, has achieved a considerable degree of acclaim in his adoptive country for his work. Intimately involved in both progressive politics and avant-garde cinematography for more than 30 years, he was awarded a Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 2008 for his contributions to filmmaking, among other honors.

Among some, he’s a cult: his auteurial style is revered among devotees of activist film for its interweaving of archival and new footage—and soundtracks—to yield meditative, non-narrative takes on the history of inclusion, difference, and the post-colonial diaspora.

The Lisson exhibition features two new films: Auto da Fé, a lyrical expansion on the ideas of his celebrated 2015 Venice Biennale video Vertigo Sea on the theme of forced migrations over the past several hundred years, and The Airport, which Akomfrah describes as a “Proustian” dive into modern Greek history occasioned by the nation’s recent financial meltdown. With long, gorgeous shots of actors in period dress overlaid with classical music and occasional audio news clips, these films are open-ended musings on two of the major crises animating our times.

Just days before the now-notorious British referendum, Artspace’s Dylan Kerr met the filmmaker in Lisson Gallery to discuss not only his thoughts on the Brexit and the increasingly divisive political climate in the West but also the role avant-garde can play in precipitating political change, and why an understanding of history gives him hope for the future.

You’ve been making films about the frictions of assimilation in modern, diverse societies throughout your career, concerns that are certainly at the fore of the current referendum.I have to ask you: what are your thoughts on the Brexit?

This is one of the very reasons why historical insight is always useful. UKIP [the United Kingdom Independence Party] is one of the political parties, along with the French National Front, that have come into being solely on the basis of immigration. They exist as a kind of discontent space for people who are afraid of “refugees.” They run this poster campaign in which the explicit assumption is that we are going to be “flooded by refugees.” This is all done as if we have no role at all in this drama, as if we’re a passive bystander about to be flooded by forces beyond our control, and certainly without our involvement of any kind. It has forced that debate into the public arena.

Like many progressives or people on the left, I don’t want this discussion. Because there is an argument to be made for both remaining and leaving. Both arguments seem to me to be resting on whether or not staying or leaving will give ordinary people more power to control our own lives. But I don’t think that’s what the discussion is about. The discussion is whether or not we remain in Europe. One, because those who say we should remain say that if we do, would get business as usual.

Is business as usual good enough for most people? I don’t think so, but, let’s put that aside for a moment. I have less problems with that lot than I do with the leave lot. The leave lot are really quite seriously deranged and deluded, because from the far right to the center right this is a group of people who say we should leave because then, “We will get our country back.” And, we think, what are you saying?

When you pick it apart further, they say, “We want Parliament to be more in control.” It just so happens that so would I, but that’s not the world we live in [laughs]. We live in a world where politicians actually have very fucking little to do with how the world works. I don’t see how Parliament will improve our dealings with these huge corporations that run most of the world. That is the reality.

Leaving will make not one iota of a difference. In fact, there’s every argument to say it should make things worse, because our ability to negotiate with these behemoths would diminish. I think things will be a lot worse. My main problem with leaving is that it’s a fantasy based on a fantasy, which is based on a really scary, near-suicidal political strategy that also happens to be anti-foreigner and anti-outsider.

What do you think your reaction will be on Friday if the referendum passes?

Good question. I don’t know, but I think it’s a very real possibility. It’s a tough one, that. Clearly, flight from that space is an option [laughs], but it’s not one that I would want to take up. If that happens to be the case, as a culture, as a nation, we would be in very serious trouble. Even on the terms that are defined by the leave campaign, we’d be in very, very serious trouble because I don’t think any of the things that they think we’re going to get are even remotely in the cards. What’s even worse is that they might start a process of reversal that very few of us understand the consequences or implications of.

I’m like everybody else who’s by default in the remain camp. You’re sort of just hoping that this will be a common nightmare from which you awake and everything will be fine. You’re hoping, and you’re sending emails and texts and Facebook messages to people saying, “Please, please, please stay with the program.” But, yeah, there is a very real possibility that come Friday, we will not be in Europe any longer, and that’s a really scary possibility.

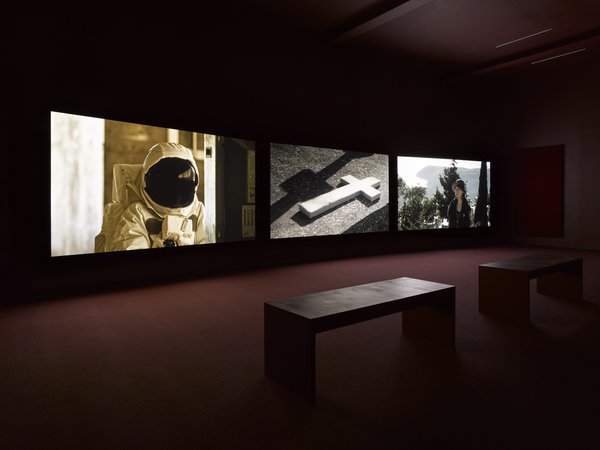

Installation shot of The Airport, 2016

Installation shot of The Airport, 2016

It seems like in the current political moment, the concerns that have long informed your work are as urgent as they’ve ever been.

I think that there are certain permanent disturbances—permanent fault lines, if you like—and they’re to do with how inside and outside fold together, how political subjects who do not yet have a voice acquire one, or how outsiders become integrated into existing orders.

These seem to be the permanent questions, and they’re bound up with our modernity. These are really questions that start with the opening up of this part of the world and old Europe in the 15th century, and I don’t see that there’s ever going to be a moment when those are permanently banished.

I think there will always be political subjects or social subjects whose need for inclusion will ask questions of existing orders. Where they will come from or how they’ll be brought into being will obviously depend on each historical moment, but that seems to me to be the nature of how the social will always be constituted in modernity. Different people will move into that spotlight, and then—whether the key questions they bring are resolved or not—at some point that spotlight move to something else.

When you see things like the rise of far right movements in Europe or the popularity someone like Donald Trump here in the States, do those read to you as more of the same?

That’s interesting. Put it this way—I think the invocation of the historical can never be an excuse for complacency in the present. I can’t say to myself, “Oh, because this happened in the 15th century, let’s not care about it now.”

The invocation of the historical is simply a way of alerting people to an existing narrative that someone like Trump or the far right in Europe are tapping into. It’s not to deny them effectivity or to court indifference to the impact or damage that their presence will cause. It’s to say that sometimes it’s best not to treat them as just isolated cases, because they form part of existing narratives which can be faulted and have been in the past. That can be done. In a weird sort of way, the invocation of the historical is to empower rather than to disable.

There are discrete moments in the past that you can point to and say, “Look, here’s where we overcame an obstacle.”

Indeed. I live around the corner from a very, very famous street in the east end of London called Cable Street. Cable Street was the place where in the ‘30s, the Blackshirts—the then British far right—wanted to march through this Jewish neighborhood, and the neighborhood community came out and said, “No, no, no. You’re not going to do this. Not on our patch.”

For several decades afterwards, every time a new anti-fascist or anti-Nazi group formed itself, it evoked this moment and its key phrase—“never again”—as a way of empowering itself. One can make allies with history in the service of good—it is possible, and one should do it. It’s not to say, “Because of what happened in history, let’s just forget about it because it will happen again.”

The fact that these events are part of a continuing narrative that isn’t new and also isn’t going to end actually becomes, in a way, cause for hope.

Yes, yes. It’s a cause for hope in the sense that what appears to be an emergency, wholly of the present moment, is that as well as something that has happened before. It’s an indication of how one could address it as we have in the past, or how one could learn about the contemporary rhetoric by looking at the past. It doesn’t help anyone to see Trump as a unique form of demagoguery. He’s using phrases and narratives that rely on earlier iterations.

Still from Auto da Fé, 2016

Still from Auto da Fé, 2016

How do the two films showing at Lisson speak to this contemporary moment?

Auto da Fé is a very good example of, in a way, the conversation we’re having. I’m increasingly concerned about the way in which refugee issues are discussed in Europe. I started to look at that in a piece that I did three years ago called Vertigo Sea. There we dealt with the question of migranthood and refugeeship in relation to travel via the sea. This time, I thought, “Ok, something else is going on here that’s worth unpacking.” It seems to me that what was going on was something I knew something about, but that I had forgotten.

In 2009, I went to the Caribbean and found myself standing in a cemetery that someone took me to because, for them, it’s an old cemetery. But, what struck me when I first went to it is that it’s actually an old Sephardic cemetery. As I looked at the tombstones, I started to realize these are people who moved from Latin America—Brazil, mainly—to the Caribbean sometime in the late 17th, early 18th century. As I looked, I realized that many of transformations in their lives seem to coincide with the inquisition in Brazil. These were migrants, but they were migrants in flight from modes of terror, modes of annihilation.

This was something I stored away, and I didn’t really think about it again until I started to look at the Syrian migrants. There are similarities there. It’s not that they’re the same, but it felt to me as if the existence of this 350-year-old narrative of dispersal and flight, usually against a backdrop of some kind of conflict, suggested that they may well be running alongside the "Founding Father" narrative of migration, where people want to move, they move, they settle, and they build something.

There’s this other story of people who have to leave because they’re in trouble, quite literally. That narrative is as old as the other one—Isabella of Spain is kicking out Moors and Jews at exactly the same time that Vasco da Gama is sailing to India. It seemed worth seeing whether another narrative of migration, a counter-narrative if you will, of migration as refugeeship could be constructive. That’s what I was trying to do with Auto da Fé.

Now, that’s very different—but in a way similar to—The Airport. With that film, again, I was alerted to the subject because of something called a “crisis”—this time not a crisis of migrant and refugee issues, but of a different kind of crisis: the economic crisis of Greece. I went there looking for a way of grounding the interest, and when I saw this airport I said, “Wow. That’s it.”

What was it about this particular airport?

The airport is the old international airport of Athens, which was closed so the new one to be built for the Olympics. Airports have this weird space in a national imaginary, because they’re projections of what the nation feels they’re about. If you have an international airport, you’ve arrived in modernity [laughs].

It’s possible to turn an airport into both a symbol as well as a metaphor for national projections—or national fantasies, if you will—about how we better ourselves. It could be the preceding march through which you look at, basically, a century of Greek attempts at solitude, of finding a better life.

When someone says there’s a crisis, in a sense that’s what they’re talking about destroying. It’s that century-long memory of different attempts to come into being—to be Greek. To be in the 1890s, 1920s, ‘30s, ‘40s—these are all the moments that the Greeks were being told there was a problem. The crisis in the case of Greeks was very particular. You were being told, “Ok, everything you’ve done up to now is a problem. You’ve lived beyond your means, you’ve spent too much money—basically, you’re a failed state.”

The implication being “your normal is not right.”

Yes, your normal is not right. It feels to me that then is the chance, the moment where people say, “Well, what is not normal about the attempt to be a modern nation over a century?” You’re talking about lives, about working people over generations who are trying to better themselves. That’s not a crisis.

Still from The Airport, 2016

Still from The Airport, 2016

What’s a better way of thinking about these issues beyond the crisis narrative?

It seems to me that there are some things you can’t deny. There was clearly some form of economic meltdown. But, the notion of crises being evoked seemed to me too totalitarian in its implications. Even if that wasn’t the case, it seemed to me that one of the things artists, filmmakers, or image makers could do is to look at the Proustian implications of this moment.

What do you mean by Proustian here?

In his last book, Time Regained, Proust starts to talk about the involuntary memory—through the scene with the madeleine—when suddenly mundane things, which are supposedly just that, spark off other ideas or associations. I was very, very conscious about trying to use that approach to deflect and maybe even to humanize this definition of crisis that we’re talking about. People begin to see that what is the stake are not just things in the present—we’re also talking about things in the past.

We’re talking about moments of arrival—endless arrival—in Greek life over a century in which people were trying to make a better sense of where they were going. And, as you know, they were being denied that. When Merkel and Cameron spoke to Greek prime ministers, they were almost speaking to them like kids: “Oh, you misbehaved. You overspent, therefore you need to be punished.” It’s like, “Hang on, you’re talking about a national disaster, first and foremost, for Greece.”

There’s a way in which what you’re watching is the collapse of a century-old dream, if you like, to make something called a Greek state. It’s not that old a state. It’s something people fought for in the 1880s. It came into being as a collective will for betterment, and it’s that which has now run into the ground. This is not the time for us in the West to jump in and wag fingers, especially when some of us are actually culpable.

That to me was the great irony of the situation, that Western European states were saying “naughty, naughty” to Greece when in fact those same states helped to create the problems in the first place.

Yes, we affected shit. Whatever the shit was, we had certainly more than a little hand in it.

Can the same be said for the refugee “crisis” that’s happening right now?

Yeah. One of the modern ironies is that, really starting with Bush and Blair, a number of these so-called humanitarian gestures at resolving conflicts across the world are cause for military interventions, which then have these knock-on effects. So, we create these war zones that are basically not conducive to sustaining life [laughs].

People say, “Ok, this is now a toxic space. I need to leave this.” Then, at the moment when they cease to take the toxic space that we said is a humanitarian gesture on our part as theirs, we suddenly get all amnesiac. “Oh, wait, wait, what are you guys doing here?” we say. And they say, “Well, we’re from the warzones.”

That you created.

That you created. And we say, “Oh, no, no, we were just trying to help.” You know what I mean? It’s just a weird state of affairs, and it’s almost as if we forget not just that we were active participants in the becoming of this drama, but that we’re continuing to participate in what we started. We’re still doing it! It’s a very strange form of amnesia built on this schizophrenic understanding of both our agency and the results, the consequences, of that agency. “Oh, we haven’t done anything.” It’s not that you haven’t done anything—we are still doing things.

Installation shot of Auto da Fé, 2016

Installation shot of Auto da Fé, 2016

In light of everything we’ve been discussing, what do you think the role of avant-garde artists and filmmakers like yourself have in these kinds political debates? What kind of power do these kinds of socially conscious works possess?

One of the reasons that I do what I do is because I am interested in that question. What I know for a fact is that it’s not something you can answer in advance. I think part of the problem with waves of the avant-garde in the past is that they’ve tried to put the cart before the horse of work, the horse of process. The horse of process and engagement has to be the focus of our activity, because in a way the impact of that activity, the “political” reverberations, are almost an outcome of that work. It’s not something that you can know advance of doing it.

Again, this is not necessarily a recipe for passivity or lack of engagement. What I am saying, though, is that I think if you wanted to read off what an artwork is going to achieve in advance of doing it, you’re lost. This is where we end up with socialist realism [laughs].

It seems to me that the task of any avant-garde is not to prescribe or to be prophetic in its decision-making. The thing is to hope that the work will have resonance and reverberations and enter into contact zones with the present in which it has some meaning and some value. But one cannot know that in advance of doing it. That seems to me to be the very reason why one should do it, not the opposite.

It’s important that we know certain things. I know that works have political reverberations and implications and impact. I know that. I’ve lived through enough to see what works and to know that I can do that. I know that there’s no way of prescribing what that impact will be in advance of the work.

I also know that’s no reason for not doing certain kinds of work. That you can’t predict the outcome is not an excuse for not doing something, but one has to remain, it seems to me, absolutely agnostic about this question of the work’s value until it starts to circulate. Even if you lose that several times, even if these particular works here have no reverberations whatsoever, that in itself will still not be an argument for believing that they couldn’t.

Is it because you know, by looking at history, that there were works like this that have had these positive effects?

Yeah, they do. I know that for myself, from my own life—it’s not something that I’m just hoping to happen. I know that had I not walked into a cinema at several moments in my life and see certain kinds of films or read a certain book, I would have gone a very different route. I know that you can change the molecular structure of how people imagine themselves and their futures.

It’s such a deeply optimistic, hopeful ethic to have.

Ernst Bloch had this absolutely right in the third volume of his books on utopia. The thing to become cannot necessarily be known in advance of its arrival, but that is by no means a reason not to prepare for it [laughs]. Every good religion has known that for a while. I don’t know what political narratives can’t understand.

The utopian impulse that is present in all images, which always arrive to us, me and you, as utopian promises. Tarkovsky made Mirror and moved on a decade before I saw it, but built into its conception and its production is this idea that one day, someone like me would see it, and that my encounter with it may yield results. I was 16 when I saw Mirror—I didn’t get it. I didn’t know what the hell it was about. But I had a sense that there was some beckoning to it elsewhere that the film seemed to be speaking to me, something I didn’t get until later.

To conclude, what one piece of advice would you give to a young artist or filmmaker who’s trying to figure out how they ought to work?

Seek out mistakes. Make as many as possible. In fact, I would say making mistakes will probably the best thing that will ever happen to you. Have courage and do it to best of your ability, because in those mistakes will lie your uniqueness. The mistakes are what somebody else hasn’t done. That will be what you do, and they might feel at the beginning as mistakes, but actually years later, they will feel like signatures.