When I met artist Mieko Meguro in her Soho apartment, Dan Graham sat at the kitchen table eating from a bowl of ice cream. “I’m eating some gelato that Mieko disapproves of,” he said to me, “…too many chocolate chips.” I couldn’t help but laugh at the sight of this legendary conceptual artist—known for his multi-disciplinary approach to tracing the relationships between architecture and it's inhabitants—as an ordinary husband. In fact, this humble, humanizing perspective of Graham is exactly what attracted me to Meguro’s work in the first place.

For last year’s "Couch Potato with Dan" at Greene Naftali in Chelsea, Meguro created a sparse living room installation inside the space’s front gallery. Throw pillows adorned with embroidered illustrations of Graham were dispersed along a homely green couch. Across the room a television played a few of Graham’s favorite movies on loop—precisely, a lesser-known Godard film and episodes of the short-lived Comedy Central series Primetime Glick. Along the walls were graphite drawings of Graham performing everyday activities: talking on the phone, locking the door, or clutching a stuffed Panda as he slept in his bed. Meguro’s installation provided an intimate view of Graham, demystifying one of contemporary art’s most heralded practitioners. “In Japan, I read a magazine that explained Dan’s work and it said, ‘most difficult artist to understand,’” she said with a laugh. “Everybody makes Dan out to be a serious and grumpy artist, so I wanted to show the world that Dan is really a funny guy.”

This month, at New York’s Shoot the Lobster, Meguro has staged another show revolving around her husband and muse—but the story behind the exhibition is a bit darker and dramatic than one might think.

Mieko Meguro, Exhausted Helium Homage to Andy Warhol after Nobutaka Aozaki, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Shoot the Lobster, photograph by Jeffrey Sturges

Mieko Meguro, Exhausted Helium Homage to Andy Warhol after Nobutaka Aozaki, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Shoot the Lobster, photograph by Jeffrey Sturges

Meguro met Graham in Japan when she was in art school and he came to lecture as a visiting artist. She decided to skip her summer vacation to attend Graham’s seminar, and she sees the moment as a pivotal turning point in her life. “I thought, oh my god, I’m doing something wrong.It was the first time I felt like I was in contact with real art. It felt like a tsunami and an earthquake were coming together,” Meguro told Artspace. After first meeting, Graham and Meguro kept in touch, saw each other sporadically, and after a few years, became a couple. “I never imagined we’d end up living together, marriage, anything like that,” she said—nor did she imagine that their life together would become a main influence for her work.

Last summer, however, Graham and Meguro’s world turned upside down. Dan had a series of seizures, one after the other, and Mieko rushed him to the hospital. Forced sedation, then a coma, then a rare bacterial infection caused Graham to remain in the hospital for months, his condition uncertain for a prolonged period of time. “I really worried about him, and I had no energy to eat anything,” Meguro recounted. “I really didn’t want to leave him alone, I wanted to be next to him… so, I started eating potato chips.” Forgoing a usual meal, Meguro would take a break, walk to the hospital’s gift shop and buy bag after bag of potato chips, shuffling back to Dan’s bedside right after.

Meguro decided to hold on to the bags, remembering a piece she had seen by Japanese artist Nobutaka Aozaki, where he flipped chip bags inside out and filled them with helium. After each long day at the hospital, Meguro returned home and turned the bags inside-out, and her collection steadily grew. During these grueling few months, however, Meguro began to feel that, “I am the one exhausted. I am the exhausted helium. I can’t fly anymore. I can’t do anything anymore.”

Exhausted Helium then became a poetic way to measure time and despair—a souvenir of sorrow. The whimsical title pays homage to Aozaki, while explaining why the bags in her version would not float. Its simplicity is its strength, the bags a shiny spectacle that hold an incredibly personal significance for Meguro, Graham, and those aware of the backstory.

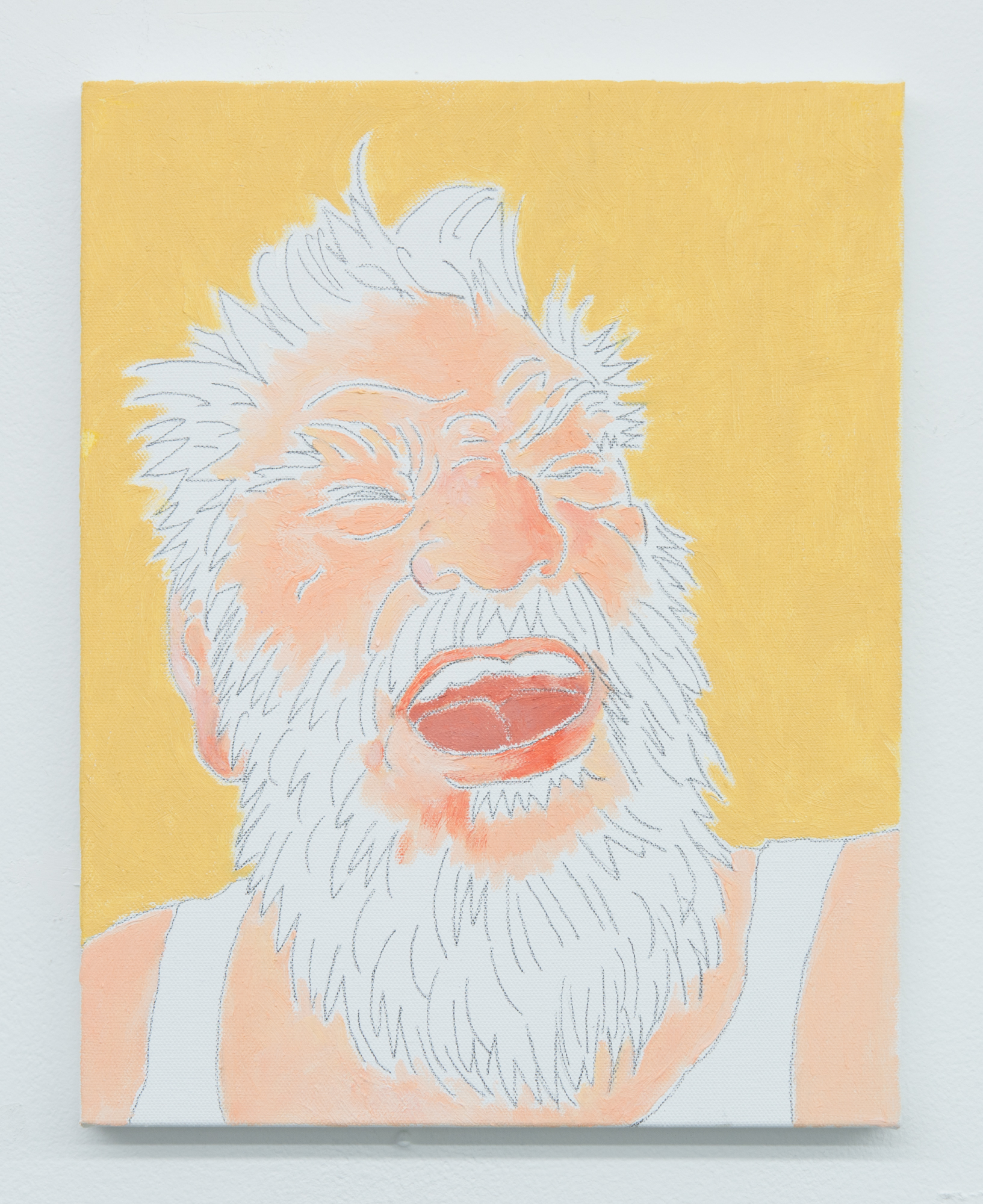

Mieko Meguro, Dan, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist and Shoot the Lobster, photograph by Anthony Atlas

At Shoot the Lobster, new paintings of Graham—tight close-ups of him laughing, smirking, and gazing off into the distance—hang opposite the chip bags. These paintings were made after his hospital stay, during Graham’s road to recovery, and they communicate all the joy and hope that comes with recovering from an intense trauma.

For My Love, Dan and Potato Chips is on view until the end of the month. Even though the show’s subject matter is somber, the exhibition itself should be seen as a celebration. “Every day,” Mieko told me as I left their apartment, “he is getting better.”