Biennials, like artists, have shows that can make or break their reputations—and that set the bar for exhibitions to come. The Havana Biennial of 1989 fundamentally changed the art world by showcasing artists of the then-called “third world” on an international level outside hegemonic European and American institutions. When Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor was appointed director of Documenta 11 in 2002, he redefined what it means to have a truly global exhibition of contemporary artists. These were exhibitions that changed history . The Whitney Biennial of 1993 was arguably one of these watershed moments. With this week's opening of the 2017 Whitney Biennial within a politically tumultuous moment in history (or what the 2017 curators describe as a "turbulent society"), we reflect back on the show that altered the way institutions address identity and the politics of race.

The 1993 Whitney Biennial was one of the most criticized exhibitions in history; incidentally, it was also one of the first times a prominent New York institution unapologetically addressed identity politics. The show spotlighted many under-known artists of color that covered issues like AIDS, gender, and the construction of sexuality and race during a politically charged environment not entirely unlike our current moment. Following the end of the Gulf War and the Bush administration, Clinton’s inauguration in 1993 was marred by a rough start; in February the World Trade center was bombed, and although only six lives were taken (a small number relative to 9-11), it was the first major stab at America’s ego from the inside. That July, the LGBTQ community was once again threatened following Clinton’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, which barred openly gay people from the military. Race relations remained tense as the brutal police beating of the young African American Rodney King sparked the Los Angeles riots of 1992. And finally, the art world itself was fundamentally changing underneath the heyday of globalization, with an unprecedented rise of biennials, art fairs, and international blue chip galleries around the globe.

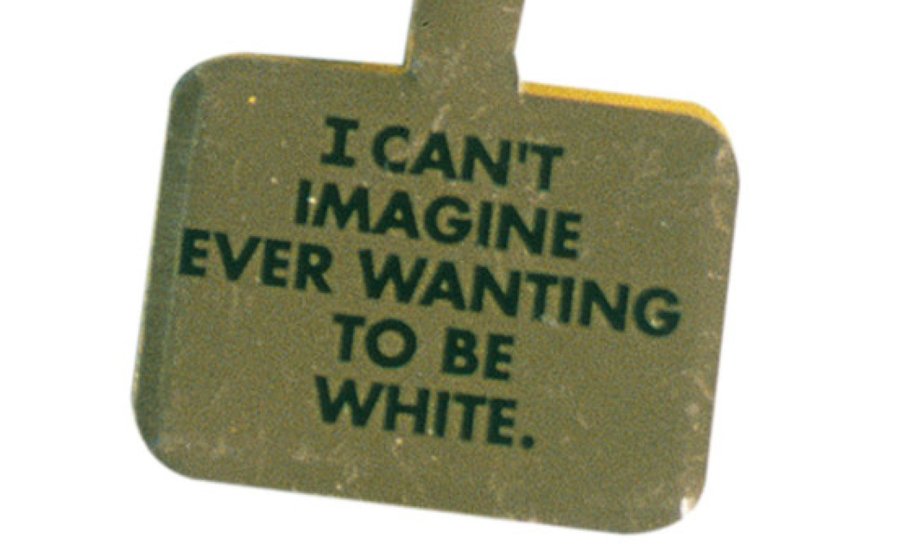

![]() Daniel Martinez,

Museum Tags: Second Movement (overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members

(1993)

Daniel Martinez,

Museum Tags: Second Movement (overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members

(1993)

In the midst of this tension, the '93 Biennial curators (Elizabeth Sussman, Thelma Golden, Lisa Phillips, and John G. Hanhardt) placed a video of the Rodney King beating on replay right at the entrance to the exhibition. Although smartphone videos of police brutality have become almost proverbial in our current world, to set the tone back then with a controversial and upsetting video—and a non-art object—was a bold statement: race was unavoidable and institutions could no longer ignore it. Artist Daniel Martinez’s contribution also confronted the traditional viewing experience; in place of the standard museum admission sticker, all visitors were required to wear buttons that featured a segment of the following phrase: “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white.” Depending on the time of day, viewers received either buttons stating “I can’t,” “imagine,” “ever wanting,” “to be,” or “white”—regardless of their race, ethnicity or gender. Inside, Robert Gober reprinted articles from New York newspapers and scattered them in bundles throughout the building, altering their front pages to highlight media's distorted coverage of gay rights and AIDS. Even pedestrians outside the museum were implicated in the biennial's political curatorial decisions; the curators hung Pat Ward Williams's photograph of a group of young African American men on a window facing Madison avenue, addressing passers-by with a direct question: "What You Lookin At ?" (the phrase spray-painted on the photo.) Rather than simply spotlighting "political" artwork, the curators politicized their very own strategy, troubling traditional exhibition display and curatorial procedure.

Installation view of Byron Kim's,

Synecdoche

(1993), at the 1993 Whitney Biennial

Installation view of Byron Kim's,

Synecdoche

(1993), at the 1993 Whitney Biennial

As a result, the show was one of the most criticized in history and for one primary reason: the artists were said to engage in a simplistic “politics

of

identity” rather than making identity

political

. Critic Eleanor Heartney described the biennial as “social work or therapy” with pieces that were “numbing didactic,” and said that too many of the “most prominent works simply target the white male power elite as the source of all evil.” One such example of “numbing didacticism” was Byron Kim’s

Synecdoche

(1993). Composed of small monochrome canvases painted in skin-toned hues, the work was dismissed as merely stating the obvious: that people come in different colors. What this quick-handed criticism fails to consider though, is how Kim was forcing the “pure” modernist grid and the “neutral” legacy of

Minimalism

to confront what it had always disavowed: race and an embodied spectator. Kim was making art history’s treatment of identity and race

political

rather than preaching a literal “politics” of diverse identity.

Gary Simmons,

Lineup

(1993), 1993 Whitney Biennial

Gary Simmons,

Lineup

(1993), 1993 Whitney Biennial

Some of the most well-known artists of today, like Fred Wilson , Mike Kelly , and Robert Gober, were similarly criticized for their “simplistic” work on race, adolescence, and homophobia. Ironically, the show's second-most-common criticism by conservative critics was that the biennial needed more works in traditional mediums like painting. According to them, the work was too directly political and social in its content, and too ephemeral in its composition—leaving no room for the privileged space of neutral aesthetic contemplation that the modernist white cube had always provided critics in the past. Even in the '90s, Clement Greenberg ’s rampant Modernist formalism of the 1950s lived on.

Detail of Pepón Osorio's

Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?)

, (1993), 1993 Whitney Biennial

Detail of Pepón Osorio's

Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?)

, (1993), 1993 Whitney Biennial

So, if the 1993 Whitney Biennial received such harsh criticism, what positive effects could it have on exhibitions to come? The major institutions of New York could no longer ignore their own exclusions of artists of color and the political realities around them. (Of course, museums like El Barrio and The Studio Museum in Harlem, which had been around since the '60s, were already addressing these issues.) Exhibitions like Thelma Golden’s “The Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art” (1994-95) that followed were exemplary of an institutional change to come within the Whitney itself. And while the '93 biennial didn't inaugurate a game-changing diversity consciousness within institutions (let's face it: the majority of artists represented in museums remain white, male, Euro-American, and heterosexual), the '93 biennial changed the ways an institution itself can engage in the politics of race and identity. (Today, one would like to think that the Whitney’s upcoming retrospective on the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica is symptomatic of this change.) As the “Museum of American Art,” the Whitney has come to realize that in our age of globalization, any singular notion of “American” art might no longer exist.

Installation view of Fred Wilson's

Guarded View

(1991) included in Thelma Golden's "The Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art" (1994-95) at the Whitney

Installation view of Fred Wilson's

Guarded View

(1991) included in Thelma Golden's "The Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art" (1994-95) at the Whitney

With this in mind, the stakes couldn't be higher for this year's Whitney Biennial, which opens this upcoming Friday in the museum's newly-opened Gansevoort Street location. If the 1993 show challenged what it means to make an exhibition political —through additions like the Rodney King video, Martinez’s buttons, and its unprecedented spotlight on identity politics and race—then today this model seems more relevant than ever. If “the formation of self and the individual’s place in a turbulent society” is one of the key themes reflected in the work of the artist for the 2017 Biennial, we might pose the same question to the institution itself: what is the role of art institutions in this turbulent society we live in?

Park McArthurs, installation view of Ramps (2010-2014), Essex Street Gallery, New York

The list of artists selected for the 2017 is provocative. It varies between emerging artists like Puppies Puppies to established artists such as Anicka Yi, the recipient of this year’s Hugo Boss Prize. Park McArthur, like Byron-Kim, forces the Minimalist legacy to confront disability as she transforms handicap ramps into sculptures. The confrontational spirit of the video of Rodney King’s beating is equally addressed in the work of Cameron Rowland, whose show at Artists Space last year linked incarceration, labor, and race through prisoner-made objects. The interdisciplinary collective Postcommodity (comprised of indigenous artists Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martínez, and Kade L. Twist), is most well known for its temporary land art installation Repellent Fence (2015) that ran across the U.S.-Mexican Border—both a harrowing critique of U.S. pesticides and a connecting force between Native Americans and indigenous tribes in Mexico. This year, Occupy Museum (comprised of Arthur Polendo, Imani Jacqueline Brown, Kenneth Pietrobono, Noah Fischer, and Tal Beery) will continue their ongoing project “Debtfair,” which invites artists to share their experience of debt and calls on them “to join us in empowering ourselves around our economic condition.” The collective most notably spearheaded the #J20 Art strike that demanded all cultural institutions to close on inauguration day. Whitney director Adam Weinberg refused the call, opting instead to make the institution free for the day and host guided tours and discussion panels, begging the question: if the Whitney refuses to close its doors in solidarity, then how can it keep them open to provoking discussion about the "turbulent society" that lies outside them?

Postcommodity,

Repellent Fence

(2015)

Postcommodity,

Repellent Fence

(2015)

The Whitney Biennial of 1993 put identity politics—as both theme and curatorial project—at the forefront of its mission, creating arguably one of the most political exhibitions in history. Today, we might ask just how the biennial of 2017 can match this legacy. We are indeed living in a “turbulent society” now more than ever, however the question becomes now: What role do art institutions play in this society? Are they places to pacify political interests in name of aesthetic contemplation, or rather incite dissents and challenge our perspectives in a “post-truth” society?