Housed in an elegant cast-iron building on Grand Street since 2006, José Freire’s Team Gallery has been the one of the last holdouts of the SoHo art scene, using its off-piste location as a staging ground for exceptional shows that push boundaries in every which direction. From the exuberant nudes of Ryan McGinley to the future-shock machinations of Tabor Robak and Cory Arcangel to the lavishly jazzy abstractions of Stanley Whitney, the gallery’s program has been a testament to the grit, tenacity, and infinite resourcefulness of its founder, who managed to steer his business through two decades of tumultuous change—with stints in the East Village, SoHo, Chelsea, and now SoHo again—without losing the rock-and-roll edge that has endeared it to curators and collectors alike.

Now, at a moment when former MoCA director Jeffrey Deitchis poised to once again make SoHo a buzzy art destination with his return to 18 Wooster Street (taking the property back from the Swiss Institute), Freire is closing one SoHo space and mulling his next move as Team Gallery’s 20th anniversary approaches this October. Considering that the Spanish-born, New Jersey-raised dealer has always been led by his finely attuned aesthetic sensibilities—he once went an entire year without showing a single artwork in color, a feat which he says “wasn’t planned”—there is considerable curiosity about where his next steps might lead.

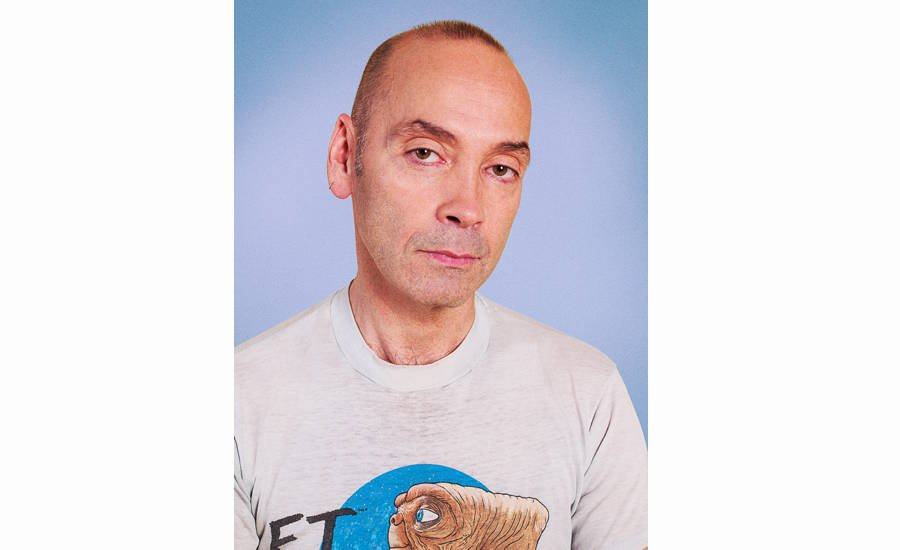

To find out what we can expect, Artspace editor-in-chief Andrew M. Goldstein sat down with Freire to talk about the extraordinary saga of the gallery, where he feels art is headed next, and why Harlem looks like a better bet for his next destination than the Lower East Side.

You have had an exceptionally rich and varied career, so it’s probably easiest to start all the way back at the beginning. How did you first find yourself drawn into art?

It was completely accidental. I moved to New York in 1979, and between then and 1983 I actually worked in the music business. I did a lot of things there—I was a personal assistant, and I also tour-managed for a lot of lesser known bands on Factory and on Rough Trade like Quando Quango and 52nd Street and the Virgin Prunes. They were all 11-venue tours, so they would play 11 cities over something like 20 days, and I would accompany them to get paid by the venue, give the performers their per diems, and report all the funds back to the person who booked the tour in New York.

I can imagine that must teach you some valuable skills in talent-wrangling.

Yeah, how to talk to talent. I always think I learned how to talk to talent then.

That must have been fun. What made you transition into the art business?

The lure of New York City, and living in it at nighttime, was really very romantic to me, but by the age of 23 I was completely burned out. Through a friend of a friend, I met a gallerist who hired me to work the front desk at her gallery, and that was Phyllis Kind. She’s from Chicago and people think of her as a Chicago-based gallerist—the primary artists on her roster were the Chicago Imagists, so she showed Christina Ramberg, Ray Yoshida, Jim Nutt, Gladys Nilsson, Roger Brown, and Ed Paschke—but when I went to work for her she had a space on Greene Street, where she showed contemporary art on the ground floor and outsider artists simultaneously in a basement gallery. So, Henry Darger was actually the first artist whose work I ever handled in a gallery. It was an unusual gallery on which to cut one’s teeth because it had these parallel programs.

How did she end up with that combination?

If you look back at a lot of the Chicago Imagists, they were actively involved in the collecting of outsider art. It's something the artists brought to the gallery—an interest they had.

Did you have any interest in art before working at the gallery?

None whatsoever. It was just a job. I liked the fact that you didn’t have to be at work until 10 in the morning, and that I could sometimes show up at noon. Because I always agreed to work late, I never had any problems—and during a three year period of time I went from answering the phone and taking out the garbage to being the person who would write the press release and walk people through exhibitions. The first work of art I ever sold was from a Bill Copley show; the first show I ever walked someone through was a Howard Finster show. You know, at the time, if a gallery in SoHo had five employees, it was a big gallery. Everyone smoked, and we smoked in the gallery, so the walls were yellow. When a show came down, the only thing we would do to prepare for the next show was to paint over the marks in the wall where the nails had been—this thing like painting the entire space every month is something that did not happen in 1983.

At the end of those three years, I felt the thing I wanted to do was curate, so I found a tiny gallery on the corner of Avenue B and 10th Street in the East Village that was owned by a sole proprietor, Paulo Salvador, who needed a staff person. The first day I went to work, an artist had just canceled an exhibition, and he gave me six sets of 35mm slides and he asked, “Which one of these people do you think I should give a show to.” I held the six sheets of slides up to a lightbulb, and I picked one and dropped it on the table: “Clearly, this one. Give this girl a show.” And it was Polly Apfelbaum, so Polly was the first curatorial choice. Well, Paulo passed away in 1987. This meant I had no job, and I had to get one. So I opened an art gallery.

Where did you open your first gallery, Fiction/Nonfiction?

Salvador Gallery was by Life Cafe, and catty-corner to that was a gallery called Great House, and next to that is where I opened Fiction/Nonfiction. Now, I had a month-to-month lease, and in the East Village in the late ‘80s, the rents would go up every month—the landlord would come in and tell you that in 30 days your rent was going to double. You couldn’t really get a long lease on those small storefronts in the East Village, but in the late ‘80s, at the height of the population in the East Village, there were well over a hundred galleries. You would have little storefront after little storefront after little storefront.

I had a gallery in the East Village, the girls at P.P.O.W. had a gallery in the East Village, Lisa Spellman [of 303 Gallery] had a gallery in the East Village. Today I think we may be the sole survivors. And the spaces weren’t very advantageous—although some people like Pat Hearn went all the way past Avenue D, where she was able to get a very large space, at the time when she was showing Philip Taaffe, Peter Schuyff, and Milan Kunc, who were these painters who had very substantial waiting lists.

Pretty quickly, you moved to SoHo, first to Mercer and then to Prince Street. Why? And was this around the same time that Pat Hearn and Colin de Land, the charismatic founder of American Fine Arts, moved to the neighborhood?

As you know, the answer to all questions lies in economy, so the gallery existed at 155 Avenue B for 18 months, and then I moved to SoHo simply because it was cheaper. So, I went from a 900-square-foot ground-floor space to a 3,500-square-foot second-floor space in SoHo for a slight savings, and I kept Fiction/Nonfiction as the name of the gallery, but I put my name underneath it so I could start to take credit for it. And we all moved at around the same time. Though, I think I moved first—I was at 21 Mercer Street, and I remember Colin coming to look at a space upstairs and me hoping he would take it so there would at least be two galleries down near Canal Street on Mercer. But he settled on Wooster Street.

At this point, you had a fairly painting-heavy gallery. Who were you showing?

The first show that I did in SoHo was Marilyn Minter and Andrew Masullo. But, you know, I’m not entirely sure whether in retrospect that first gallery was more painting-heavy than my current gallery is. I have a reputation for being someone who does not show painting, but if you actually look at the exhibition histories, there’s always been painting peppered throughout the program. But I think of Team and the gallery that I had before Team as two different programs that began the way one begins a program. You don’t wake up and write the names of 20 artists on a piece of paper. You add someone, they lead to the addition of someone else, a relationship doesn’t work out, another relationship flourishes, and it develops.

And the rosters of these two entities—one whose dates are ‘87 through ‘95, and the other one ‘96 through the present—they even have overlap, because Tam Ochiai showed with me before Team, and Stanley Whitney showed with me on Mercer Street in the late ‘80s before Team. But, that first roster included John Wesley, Rona Pondick, Deborah Kass, and Andrew Masullo. Substantial group-show appearances included Marilyn Minter and John Coplans.

How did you arrive at this group of artists? Because they’re rather different from the ones in your current program, which is much more multidisciplinary and avant-garde.

I think that at first, I entered into the world of an artist through their process. What happened, however, over the years of having experience dealing with different kinds of processes, is that I started to rely more on intentionality. Why is the artist making something? What do they believe what they’re making communicates? What are the possible communications in the artwork that were not placed there through the artist’s intentions? It just meant that my mind, I think, had become slightly more sophisticated through experience. Now, sometimes, I can’t tell you how an artwork came into being, but I can usually tell you why it came into being. In my first incarnation, I would have been able to talk about the process, and I would have talked about it first and foremost.

How did that change the kind of artists you were attracted to?

I don’t know if it changed. But I think something that is very dangerous for any gallery is a mid-career artist. That’s something I believe a gallery needs a great deal of experience to handle. I think fucking up the career of a young artist is next to impossible. If there is some steam in it, the first three shows are free.

How do you mean “free”?

You don’t really have to do much. And there were a lot of artists in the first program who I think were mid-career artists. When I started to show emerging artists, it was largely because I couldn’t make any assurances financially to someone who was further along in life and would require a kind of stability. I told someone the other day that if I was partnered with someone, or had children, my gallery would have never survived. I was only able to take the kinds of risks that I took because I was not responsible to others in that sense.

When you moved to Chelsea to found Team with the painter Lisa Ruyter in 1996, you had made it through the recession of the early 1990s, which had shuttered so many of the downtown galleries. How did you make that transition?

Well, my first gallery, Fiction/Nonfiction, was born from ignorance—my ignorance about how the art world operated. And Team was born out of poverty. They’re two very different things. I had barely survived the early-’90s recession, because I wasn’t aware that if you were a gallerist with an attitude, you actually needed to be able to afford your program. What you do is you open a gallery where the rent is very, very cheap, and you know full well that if you’re going to do four shows in a row and none of them are going to sell, you better have the money to pay for them.

I suppose that’s an investment that you hope will pay off over time.

Yeah, I mean, I had shown Rona Pondick from roughly at the opening of my gallery in the East Village and never sold work. Then she was in the Whitney Biennial in 1991, and all of a sudden everything she made sold, which was a financial windfall for my gallery because I had all this inventory. So then I thought maybe I was impervious to the same financial realities that were closing other galleries on a weekly basis. But, I wasn’t impervious because I did close in 1995, riddled with debt. Most of it for taxes. So I just worked every single day, sent people money orders whenever I could, and eventually paid off all the debt.

How did you meet Lisa in the first place?

We met when she showed up to be my intern in the East Village, when I could only afford to pay her five dollars an hour. She worked for me part-time, and she worked for Marilyn Minter part-time in the ‘80s as an artist. Her own first gallery show was at Friedrich Petzel’s, in a small office space on Broadway. And, at one point, we married. So, we were actually a couple, and we were married when we opened Team.

You were married, like married-married?

Married, married, married. Yup. In 2001 we had a relatively amicable divorce, and a relatively amicable business breakup, and since then the gallery has been solely under my ownership. I think she’s a great artist, severely undervalued and underappreciated. And back in the beginning, she had her studio in the rear of the space. We always think that her studio was in the back third of the space, my gallery was in the front third of the space, and we shared the middle third. And we had one employee who worked for the two of us. And we both had desktop publishing jobs at the time. I worked at the Princeton Review. I poured text in those horrible exam prep books. That’s how I paid the rent for Team for the first two years after it opened, working nights and the dates when the gallery was closed.

What was the gallery itself like in Chelsea?

When Lisa and I opened the space on 26th Street, there were 10 or 11 galleries in Chelsea. We were the only ground-floor space on 26th Street—Carol Greene was already in the building across the street up on the eighth floor. My rent was less than $2,000 a month for about 3,000 square feet, and I signed a 10-year lease on that rent. But Team was a poorhouse, a gallery in a grotesque space about four feet below street level, so you actually had to walk down a ramp to get into it. There were tons of pipes in the ceiling, which carried all the plumbing of the building. So, the space kind of dictated what you could put in it.

How did you respond to it?

Well, the first thing is that the program of Team has been video-heavy since the beginning, because if you showed video, it meant that you could have the lights turned off so nobody could see how awful the space was. The second show was a video show.

You also began showing a different kind of artist, including a few rock-and-roll, bad-boy types who were decidedly ahead of their time. One of these was the great Steven Parrino, a legend who was totally underappreciated during his lifetime, and who you began showing in 1997. How did he come into your orbit?

Lisa and I were both friendly with Steven, so I knew his work before opening Team. I had seen a show that he did at Metro Pictures one year when I was working at Phyllis Kind, which was a few doors down, and I would walk by in the morning and see the Steven Parrino show through these big glass windows, so I thought of him as some really gigantic art star. When it became clear to me that he was available—that there was actually no gallery showing him—I made this very casual agreement with him that we knew the work wasn’t going to sell, but that that was ok. He would give me shows, I would do them, they wouldn’t sell, and then he would ask for the work back so that he could give it to European gallerists who could then maybe sell it. He was working with Rolf Ricke in Cologne, a really extraordinary figure, and Massimo De Carlo in Milan.

During the eight years that I showed Steven, I only sold two paintings. I did three solo shows with Steven, and the last one was actually the main reason for my leaving Chelsea. There were four black paintings in the gallery, and people would come off 26th Street, walk down the ramp into the gallery, and they would shrug their shoulders and they would say, “Eh, they’re all black.” And then they would walk out. I thought, if it were more difficult to get to the gallery, maybe they’d actually shrug their shoulders and say, “Hmm, they’re all black… I wonder why he made them in different shapes?” Maybe they’d ask a question.

The fact of the matter is that art neighborhoods like Chelsea don’t encourage slow viewing, and they don’t really encourage thinking. There’s a herd mentality there on a Saturday, and I thought if I moved somewhere where people really have to go out of their way to come, maybe the slower artists in the program would stand a stronger chance.

Why were his paintings, these incredibly elegant compositions of painted and crumpled canvas, such a hard sell to American audiences?

I think it’s for the same reason that Stanley Whitney was a hard sell for years. People who were in front of an artwork always worried that it wasn’t the right artwork: “What if this crumpled black painting isn’t the best crumpled black painting? Maybe I should wait to see another one.” Or, “Maybe this Stanley Whitney painting of colored squares isn’t the best one, and maybe the one he makes next will be the best one.” I could sell 95 percent of the Steven Parrino painting to anybody, I could sell a Stanley Whitney painting 95 percent to anyone, but I could never close. I think it was because people didn’t understand that being in a room with one of those paintings was a privilege, and that you needed to act on the privilege immediately.

But not only was Steven completely unsupported by collectors in the United States, he was completely unsupported by critics in the United States as well. With the exception of Bob Nickas, who did really major things with him over the years, there was no critical support for that work at all. So, it’s not like I would even do the shows and rest on the critical laurels—there weren’t any. But he was always very nice to all of my young artists. He treated them with respect, and he gave them all advice. In a way, Steven mentored Banks Violette and Gardar Eide Einarsson within the gallery structure.

All three of those artists had a very aggressive, pared down, minimal aesthetic that seemed to be in key with the direction that underground music was taking at the time.

Sarah Thornton, who wrote that book Seven Days in the Art World, said that she always remembered my gallery on 26th Street as being like a record store. I think it had to do with the kinds of people who would work the front desk.

How did Banks Violette, whose death-metal-inspired installations fusing themes of music and murder were among the most notorious works of the era, come into the fold?

I went to a space in Williamsburg called Momenta Art in 1999 and there was a two-person show with Banks when he was still getting his MFA at Columbia that was incredibly stripped down and really kind of harrowing. I wrote him a note in the gallery’s signature book: “Look, I love your work. Please call me.” And he called me, and I went to Columbia—I don’t generally go to MFA programs—in 2000 to see his studio there, and I committed to showing him at the gallery.

What was it that gripped you so much? I mean, coming from your music background, you must have recognized that this guy was a rock star.

That’s a nice and easy way to put it. Another thing also has to do with one’s personal proclivities. I have always loved Cady Noland’s work. One year, when my gallery was on Prince Street, she had a show at Paula Cooper, and I remember I left the gallery to see it every day for the five weeks that the show was up. Banks’s work seemed to me to be a logical step forward historically for her position—it spoke to me as both formal sculpture engaging with the tradition of minimalism, but also as work that dealt with this kind of criminal culture. In some ways, Cady Noland’s work is bad-boy art, but then his work becomes so bad it’s deathly. He accelerates it to the place where it’s not a disgraced politician who’s at the center of the work, but rather a serial killer. It’s just a shift, but structurally they are extraordinarily similar. A two-person show of two of them would be amazing.

Well, you actually worked with Cady Noland—you gave her last sanctioned show, before she backed away from the art world, is that right?

Yeah, Bob Nickas curated two shows for the gallery when we were in Chelsea that were two of the best shows that have ever happened in this gallery. The first one, in 2000, included Cady Noland, and part of her stipulation for appearing in the show was that she could install her work as she pleased with no interference from the gallery. So, we would leave her the keys to the gallery and let her stay all night and make her piece onsite.

What was that like, working with your hero?

Well, I treated her the same way I would a celebrity. Like, if someone who won an Academy Award came in here and tried to buy a Ryan McGinley, I would never allude to the fact that I knew what they did for a living. I would only talk about Ryan McGinley’s work. So, I never fawned on Cady or told her how important her work was to me. She’s still, to me, one of the great postwar American artists.

Now Banks Violette has followed her example, retreating from the art world for the past several years, leaving at the pinnacle of his fame. What happened?

He is not a typical artist, and I think at some point in his life, he felt the need to distance himself from the New York art world, which is a decision we all respected here at the gallery.

Unlike Parrino, he was an enormous success from the time he debuted, and part of a group of younger artists, like Cory Arcangel and Ryan McGinley who became real art stars. How did the gallery’s fortunes start to turn around?

Well, with the exception of Steven Parrino, every other artist in the gallery was young, and it was that generation of artists that hit. What happened was that curators began paying attention to what we were doing. Chrissie Iles, Debra Singer, and Shamim Momin, who were the curators of the 2004 Whitney Biennial, were very supportive of the program and really knew what was going on at the gallery. [Guggenheim curator] Nancy Spector was also a great supporter of the gallery at the time. Without that kind of institutional support, the program would have never made it.

Because between ‘96 and 2003, the gallery was a financial ruin. In 2003, the sales of every single artist in the gallery combined was less than $300,000. So, once you divide that and give half of it to the artist, it meant that I had less than $150,000 on which to run a gallery and live. It was tremendously precarious. Then came the 2004 Whitney Biennial, which turned everything around. It’s very true that the gallery’s success was cemented by that biennial, in which I had three artists: Slater Bradley, Banks Violette, and Cory Arcangel. What happened to this gallery between 2004 and 2007 is really very extraordinary.

Cory Arcangel is another young artist who became a star at your gallery. How did you first encounter him?

He had a website, which an artist that I was working with at the time—a painter named Benjamin Butler—urged me to look at. I thought, “I really don’t want an Internet artist.” But I remember going to Cory’s website on the gallery computer, our green iMac, and basically what Cory had done was that he had made every bad HTML decision possible all on one page. And, I thought, “This guy’s a genius.” It was the first thought I had, and 14 years of working with him has not changed that.

So I suppose you reached out to him then?

Yes. He came in, and at the time he was incredibly naïve about the art world—which was great because I was able to get him to say “yes” to me. The first thing I showed was Super Mario Clouds in a summer group show in 2003, and I remember looking up one day and seeing Deb Singer and Chrissie Isles and Shamim Momin in the gallery looking at this Super Mario thing, and I thought to myself, “Oh my God, they’re going to put him in the Whitney Biennial. I can’t believe this.” And they did. The truth is that Cory had institutional support from the beginning. We were selling his pieces to museums from the get-go when he was 23 years old.

Cory also did his first solo show with us in the Chelsea space, which included a hack of Space Invaders, which he made Space Invader so it’s only one alien—and it’s impossible to win. So, this idea in his work of validating obsolescence and failure is right there from the very beginning.

Did you have an interest in computers and technology at this point?

No, the fact that he worked with computers was of absolutely of no interest to me. I was a dyed-in-the-wool drug addict then and never bothered to spend any of my time playing video games. But I think it’s because I never participated in it that I never thought of it as low culture—there was nothing questionable to me at all about Cory’s Nintendo hacks as artworks. But what Cory’s work communicates, if we understand Post-Internet art in the very basic way that there are now generations of individuals who have only lived a life after the Internet, it means that cultural information at some point is more heavily democratized. You don’t have to be a student at a university and rely on the curriculum of the canon that the institution is sharing with you—you can actually surf the world.

His work was really a game-changer, opening up the way forward for so many young artists.

I think when people look back at the work he showed in 2003, it’s shocking to see that he was so fully there that young and that early. But Cory is the first person to say that he was one of several people practicing that way at that time, and that his sole luck is that he got a gallery that knew what to do with his work. We had already learned to bring artists like that to Europe as quickly as possible, because that’s where you could find support for them. So the first solo that we did of Cory’s was a booth at Liste in Basel, and we sold to a museum in France out of that installation. A lot of the foundation for his career was put down from that art fair stand.

What do you mean “artists like that”?

I don’t know—I don’t want to laud European collectors and curators over American collectors and curators, because I’ve had very strong American collectors supporting the program all along who bought work for which there was no precedent whatsoever. Eileen Cohen, who bought Super Mario Clouds from me for $2,400 in 2003, will always be the greatest collector I’ve ever met in my life. But, I do think that certain difficult positions that are either too political, or too aligned with minimalism, reach an audience in Europe more easily than in the United States because I think an American audience really loves to see an artist’s labor in the work.

It was the same with Carol Bove—I did a solo booth of her work at Art Basel in 2002, and that’s what really broke her as an artist, because European curators and collectors warmed to her work before Americans did. That same year I also showed Banks, Tam, Slater, Steven Parrino, and Carol Bove at an Armory Show stand, out of which I sold one Banks Violette drawing to Brice Marden for $640—that was it.

Going back to Arcangel, it’s unusual for such a tech-based artist to be as much of a financial success as he is.

Actually, the work only started to succeed financially in the last few years, really. Cory had a show in this gallery in 2008 when Lehman Brothers went down, and we sold not a single artwork in that show. And this was when he was on the cover of Artforum with his Super Mario Clouds. That ‘08 show had one of his Photoshop Gradient Demonstrations in too when it was $18,000 and nobody wanted to buy from me. I had a collector offer me $7,000 for it because he knew I was desperate for money—and I threw him out of the gallery, telling him, “I’d rather be buried with this thing than sell it for $7,000.” And I was later able to sell that gradient to the Museum of Modern Art, and I think the second Gradient we sold went to the Whitney. It’s only been since he had his solo show on the fourth floor of the Whitney in 2011 that collectors started to really respond.

The Whitney has been very good to the gallery it seems.

This gallery would not exist without the Whitney. No way. I would be working for some other gallery, wearing a suit every day and trying to sell things. Ryan McGinley had a solo show there. Alex Bag had a solo show there. Cory Arcangel had a solo show there. I had three artists in the ‘04 biennial, one in ‘06, one in ‘08. That institution, MoMA, and the Guggenheim have all been very supportive of this program over the years, and I have an enormous debt of gratitude to all those institutions because without them… I mean, they do influence collectors, those kinds of acquisitions.

It’s funny that the Whitney also inspired one of the great coups of your gallery, in that their 2003 solo show of Ryan McGinley, “The Kids Are Alright,” first introduced you to his work. He’s unquestionably become the most famous artist in your roster, and it’s unusual because he’s very different from everything you had been showing.

When he had the show at the Whitney, I remember thinking, “Oh my God… it’s Nan Goldin with teenagers.” I wasn’t particularly interested in it at all. Then Bob Nickas included two photographs of Ryan’s in a group show at the gallery in 2003, and I had to look at these two photographs every day for the entire run of the show. I noticed that in order for Ryan to have lit one of these photos, he would have to have gone through an enormous amount of effort. It was this very casual-looking photograph of a group of naked teenagers in a tree in the middle of the night, but I started thinking to myself, “Well, it looks like it’s lit with a klieg light, which means you have to rent this gigantic contraption… and then how do you power that in the middle of the forest?” Then I realized, “Oh my God, this guy’s work only appears to be casual—it’s really not.”

So, I had this odd epiphany in front of an artwork in the gallery, and that’s when I started to work with Ryan. And Ryan, for me, has become a real cause. Because he’s so popular. I mean, put auction results aside and whatever it is that the art world thinks defines a big young artist in 2016, because it’s nothing compared to Ryan. The way in which his work goes into the bedrock of contemporary culture is really extraordinary, and I think unparalleled. And it happens because he’s extraordinary. He is the most hardworking individual I think I’ve ever come across.

He always pushes his work. For an artist whose practice is so codified, he can walk into this gallery every 12 months and show me something I would have never expected to see, and I think that’s really surprising. Also, whenever he shows me his new work, maybe at dinner in a restaurant, he does it in this really shy way, pulling out these prints on cheap paper and handing them to me, fearing total rejection, and they’re extraordinary. So, I could have never foreseen the Animals show happening. I could have never seen the black-and-white portraits happening. I could have never anticipated the Grids show. I could have never anticipated the Yearbook installation.

Interestingly, Ryan McGinley is another artist whose work has extensive connections to a musical sensibility—going into his shows makes you feel like you’re in the middle of an amazing music video—which I suppose explains his enormous crossover appeal to the broader mass audience. How did his work and his success change your program and the kinds of artists you were looking at?

You know, building a roster is primarily an additive process. So, if you’re making stew, and all you put in it is potatoes, your stew isn’t going to be particularly good. I remember at some point realizing that a tonic for the gallery would be to work with Stanley Whitney again, so I went to him and pitched his joining the gallery in a very honest way. I told him, “No one comes to my gallery to buy abstraction. No one comes to my gallery looking for older artists. I guarantee you’ll sell nothing, but you have to come to my gallery.” And, he said yes.

One of the first things we did was a group show that included Gardar Eide Einarsson, and we were able to recontextualize Stanley so that young people were looking at it. I did a two-person booth in Miami with Ryan McGinley and Stanley Whitney because they had met and Ryan loved Stanley. Well, we sold all the McGinleys, and we sold none of the Stanleys.

How did you have to evolve as a dealer to manage McGinley’s success? After all, this is a guy who does museum shows around the world but also shoots giant national ad campaigns for Levi’s and Nike.

Well, we’ve given Ryan an enormous amount of attention, which he requests almost none of. He’s incredibly easy to work with. But we also deliver. As for this commercial work, if you look at his resume you’ll see that none of his professional credits are listed, so it won’t say that he photographed Lady Gaga twice, and it won’t say that he did a Katy Perry album cover. We’ll hear that he’s done something at a store, and we’ll say, “Ryan, you’re having a solo show at a museum in Tokyo that opens in April—please tell me they’re not going to show your work in a department store.” And he says, “Oh, no, no, they signed a contract. They’re not allowed to use my name.” He stipulates that he always works anonymously with these clients. But, I mean, it’s not anonymous if you look at it. All of a sudden you’re like, “Is that a Ryan McGinley, or does it just look like a Ryan McGinley?”

Clearly someone like Ryan McGinley opens up new vistas of collectors that most galleries can’t reach.

He also brings collectors to the art world who’ve never bought a work of art before. He does that, and Cory does that. From Cory, we get these tech people who’ve never bought a work of art, and they come wandering into the gallery, saying, “We need a Cory Arcangel.” They’ll be a software developer from Chile or something, and they’ll know everything about Cory Arcangel.

That’s amazing, because it’s been a big challenge for dealers to make inroads into that tech collector base.

Well, the tech thing for us is very exciting, and Tabor Robak is one of the single hottest commodities we have in this gallery now. We sell absolutely everything he makes. We have a waiting list that includes really major museums and major foundations, but we have no work to offer because he’s slow in producing. Cory brings these tech people to the gallery, and then they’re not afraid to buy work by Tabor Robak that’s really quite strange—like handmade computers that are generative, so the artwork is actually being written by the computer as it sits in a collector’s home.

I mean, he’s a 28-year-old artist, and his pieces are $65,000, and they’re in editions, so it’s not like I have to sell a lot of it. But they are complicated sales. When you place this work with collectors, you really have to educate them, and you can’t hide issues about archiving work and how technological work needs to be backed up in case this machine breaks or that machine breaks. It becomes a real education process, but once the collector has gone through it, it’s infinitely easier for them to buy the work in the future.

It’s extraordinary that even though Arcangel and Robak are both on the vanguard of this kind of art, they’re actually a generation apart.

Robak was 14 years old when Cory Arcangel was in the Whitney Biennial, and he saw that work because he had the Internet.

At this point, your gallery has clearly achieved a healthy amount of success in SoHo, and you’ve even opened a satellite in L.A. Yet now you’re actually shrinking your presence, closing your gallery on Wooster Street. What happened?

The Wooster Street space is in a standalone building, which means that when you sign a lease you’re responsible for the roof of the building, the outside of the building, and the HVAC system in toto. I was only given a five-year lease with increments in rent each of these years with an end date up April 30th, 2016. So, simply put, my lease has expired, and I choose not to renew it for any number of reasons. I’ve cycled nearly my entire program through that space, which means I have fresh installation views, which are so important in this digital age when we’re sending JPEGs to people who don’t actually come to the gallery.

Secondly, when I opened this space, there was a very nice empty parking lot across the street empty, and it’s now a horrible construction site where the street is regularly closed down for the entire day. At one point, a truck from that construction site backed into the front of my gallery and exploded one of the plate-glass windows. So, it’s been no end of irritation because of that construction site across the street that will probably be there for years. And because the construction actually closes the street, it means we can’t get deliveries—we have to sometimes accept deliveries at Grand Street and move it to the other building when the street is open. So, that’s been a pain in the ass. Then the lowest reason on my list of reasons to not stay in that space is the rent is also being increased from $25,000 a month to $50,000 a month, which I think is a lot of money.

So, when the rents for my three spaces on Grand Street, Wooster Street, and Windward Avenue combined were under $50,000, that allowed me to maintain the program that I want to maintain, which means being able to afford doing exhibitions that do not sell work and being able to show whatever I want at any art fair without worrying about making sales or not making sales. I couldn’t do that if I allowed that increase in my operating cost to happen.

So, what’s next?

Well, we can never give up the Bungalow in L.A. because people love it.

Which people? The artists?

Oh my God. Artists, collectors, curators, everyone loves that gallery. It’s in Venice Beach, there’s no signage. If you don’t have the address and a GPS, you can’t even find it because the entire front of the building is covered with verdant growth—it’s behind a wall of bamboo. It’s very private and domestic, so when people find it they feel like they’ve stumbled upon something secret. And we’re putting in great programming, whether it’s something of ours like a Ryan McGinley show or something by an artist that we don’t represent like Torbjørn Rødland, or we show someone out there who eventually becomes part of the program, which is what we did with Sam McKinniss. It’s a great lab for experimentation.

Why did you decide on L.A.? Why did it seem to be a necessity?

I have always liked L.A. And something that I have done historically for young artists in New York City is to sell their work to the institutions in New York, because if we all turn to dust tomorrow that’s the only thing that will actually stick. Now I have to do the same thing with the institutions in Los Angeles, and my track record of selling work to institutions in L.A. is woeful. I thought, maybe if I open a gallery in their city and program it very seriously, I will win a curatorial audience out there.

How’s that going?

It’s slow going. You can ask museum curators in L.A. if they’ve all been to the Team Bungalow, and a lot of them are going to tell you that they have no idea what that is. We just closed a Jakob Kolding show, he’s a mid-career artist who’s had shows at the Stedelijk, and we’re now showing Timur Si-Qin, which is his first solo show in a gallery in the United States.

Are you going to open another gallery in New York?

We may open a second space in New York, or we may open a second space in Los Angeles—both of these things are possible, I don’t feel any urgency to do one or the other first. But I do feel that New York is currently in transition. There is a plurality of neighborhoods available to a gallerist that was not the situation two years ago. One of the members of my staff has been looking at real estate on the Lower East Side, I haven’t been convinced. I always say, “I don’t like it. The ceilings are too low. I don’t like the windows. I don’t like the gallery next door. I don’t want to be on a block with that gallery.”

So I don’t see myself opening a gallery on the Lower East Side. There’s an entire generation of people—some of whom are now 10 years into their gallery histories—who have galleries on the Lower East Side, and I think that that should be a place for them to show their generation of artists. I don’t think that those galleries should be displaced by Chelsea galleries that are moving to the Lower East Side.

I would like to see what happens when Alexander and Bonin opens on Walker Street—I’d like to see if that has some sort of effect on the art world. Sean Kelly is moving to the Lincoln Tunnel. I don’t care much for that neighborhood, but he made the move he had to make, I think, in order to have the kind of real estate that his program requires. And I’d like to go somewhere that has some architectural sense about itself that’s different from other galleries. So, we’ll see. I don’t know, like the top floor of a warehouse somewhere on the west side in Harlem, with only interior walls, nothing on the outside? Sounds fine. For us, we’re looking at Harlem, we’re looking in TriBeCa, but we don’t have a stopwatch running.

What about the direction you’re looking to head in with your program? You have Cory Arcangel, Tabor Robak, Samson Young, and Massimo Grimaldi in your roster, who are all making work on the edge of the technological vanguard, and on your Instagram, meanwhile, you’ve recently flagged a number other artists of this variety—Max Hooper Schneider, Rachel Rose, Haroon Mirza, Ed Atkins, Hito Steyerl, and Ian Cheng—that you love. Can you explain your thinking around this quasi-paranoid kind of new art?

It’s funny because when you put those people together as technological artists, I think they’re uninteresting—even though they are all technological artists. If I continued that list, I would probably add Oliver Laric and Yngve Holen. When you use that word “paranoid,” though, it makes me think, oh my God, that really is true, is it? There’s something a bit psychotic about all that work. It feels acid-y, like somehow it’s some nasty, bubbling layer under your skin. Ed Atkins’s work sometimes actually makes you think when you’re looking at it that you’ve gone completely mad—that kind of slippage that happens in it is really great. Max Hopper Schneider will actually be in a show at the gallery in September, in a group show upstairs.

Why do you find this to be such an interesting direction for art?

Well, I think it’s where art happens to be right now. You know, this acceleration of trends in the art world where a certain kind of process-based abstraction becomes a big thing and then has to go away because we’ve replaced it with this new figurative painting… it’s become this cycle that’s kind of ugly. But if you look at a lot of this abstract painting and you put it against the history of abstraction, or you look at this figurative painting and you put it against the history of straight-up, Modernist figurative painting, a lot of these artists are not really offering anything that adds much. On the other hand, if you look at all of these artists who are working with new technologies or working in new genres, they really are making something that is unexpected. You don’t know in advance what you’re going to see.

As a final question, how does a gallery like Team manage to ensure its place in an art world increasingly dominated by massive galleries like Hauser & Wirth and David Zwirner? For instance, when Steven Parrino died in 2005, he was still underappreciated, selling in the very low five figures if at all; two years later, Gagosian took over his estate and began pricing his work in excess of $1 million. Now there are even rumors that Banks Violette may return from his sabbatical from art with a show at Gagosian too. At the same time, you’ve managed to go through several recessions without losing your star artists.

You know, people ask, “Aren’t you worried that you’re going to lose your artists?” And I always say, “You should only expect loyalty from a dog.” Because you shouldn’t expect artists to be loyal. You’re not married to them. It’s a business relationship. And I think if the gallery is able to produce for the artist, then the relationship should continue. What producing for the artist means has bit of a flexible definition. Producing for an artist could be providing constant sales, museum placements, museum exhibitions, other gallery shows, everything, fully loaded. Sometimes all a gallery can provide to an artist is a good context, and maybe on the right day, that’s enough for an artist to stay: “Oh, that gallery. I like their context.”

I think that in the art world, people like a certain kind of drama. They like to turn it into a bad television show like Dynasty. This artist is leaving that gallery, and that artist is leaving this gallery, and this gallery is doing that and that. I’m not so interested. I do think that the hegemonic pull of something like David Zwirner is maybe impossible for all of us to steer clear of. Maybe it’s a black hole that will eventually swallow everything. Because for all their spaces, I haven’t really thought much about Gagosian in these three years—all of those thoughts that I used to have about Gagosian, I now have them about David Zwirner.

Everybody has their demons. I have been lucky enough to suffer in the art world for 20 years, and to actually benefit financially from being in the art world for 10. And I don’t think I would have had the success if I didn’t have the failure. So, I’ll just continue to do what I’m doing. I would worry if I looked up one day and there weren’t young people at my openings—I think I would throw myself from the window. But, my gallery openings are attended by young people. And as long as I can keep a program in this gallery that is viable to art students, then I’m fine. Then, I’m a happy camper.