Why is David Byrne's new exhibition called How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic ? The fine artist, film maker, writer and musician admits that this concept of a way of thinking that is both logical, and also irrational, isn’t perhaps wholly original.

“This idea of non-rational logic was not something I made up,” he says in a new interview posted by Pace gallery and conducted in its West 25th Street gallery, where the show is taking place, “but I realised that it kind of resonated with both the fact that I make music and the fact that these drawings follow a kind of logic that isn't kind of based on logical or rational thinking.”

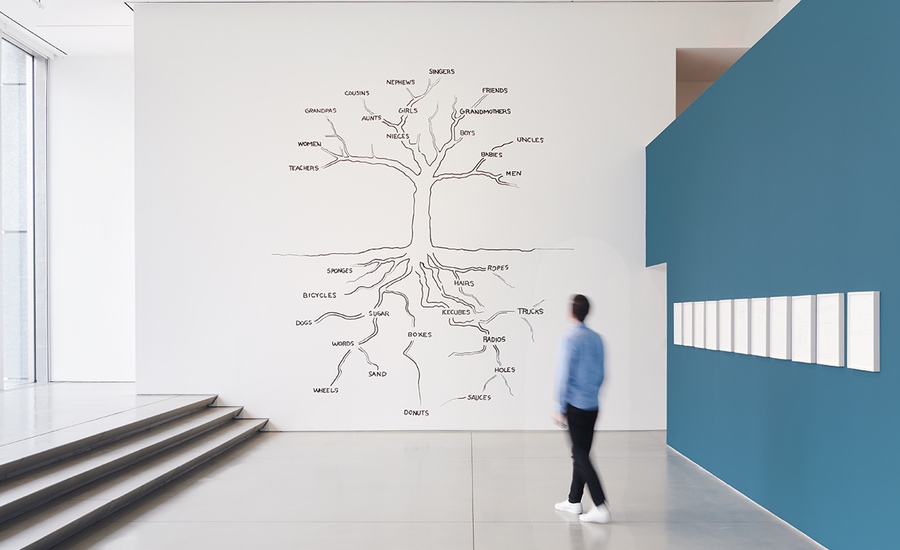

Byrne is installing a version of

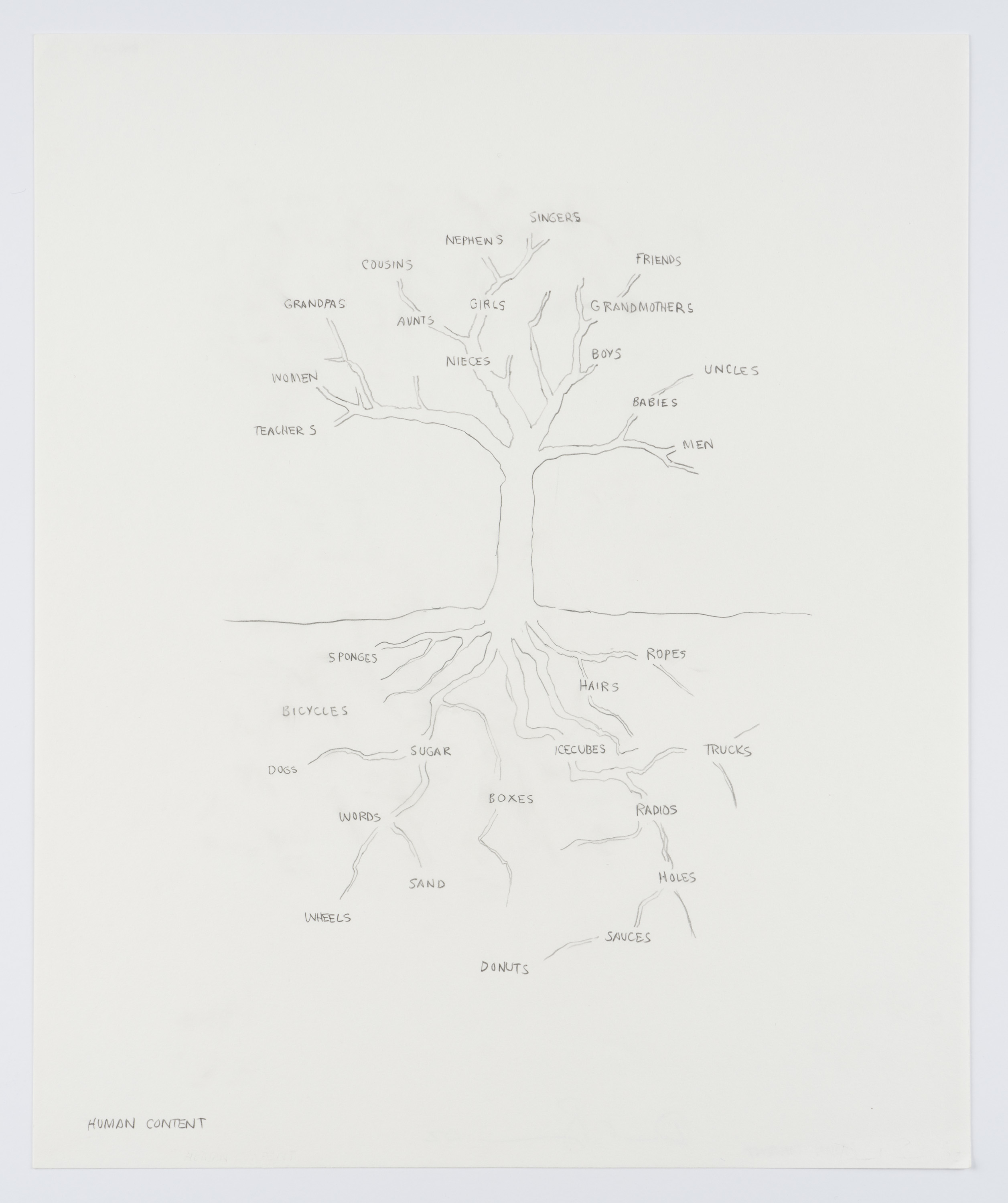

Human Content

, one of his tree drawings onto the gallery’s walls while this interview is taking place; styled like a decision tree or family tree, the branching fronds above ground link ‘girls’ to ‘nephews’ to ‘singers’, while, below the earth, the roots run from ‘ice cubes’ to ‘radios’ to ‘holes’.

David Byrne,

Human Content

, 2002, pencil on paper. 16-7/8" × 14" (42.9 cm × 35.6 cm), paper 19" ×

16" × 1-1/2" (48.3 cm × 40.6 cm × 3.8 cm), frame. David Byrne, courtesy Pace Gallery

It doesn’t make total sense, but there is, as Byrne puts it, a “kind of a dream logic”, which extends from these tree drawings (many of which date from the early 2000s), through to his more recent chair drawings (executed 2004-7), right up to his dingbat series, which the artist drew during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic and which are gathered together in a new Phaidon book A History of the World (in Dingbats) .

“Works in his dingbats series grapple with the attendant boredom, anxiety, and loneliness of quarantine as well as the inequities and injustices highlighted by the pandemic,” explains the gallery. “The dingbats are Byrne’s response to these conditions—an imaginative way of expressing hope, desire for connection, and the power of community.”

David Byrne: How I Learned About Non-Rational Logic 540 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10001 February 2 – March 19, 2022

Photograph courtesy Pace Gallery

The drawings in A History of the World (in Dingbats) , are, in their own way, completely fantastical. Yet in these images, the nude bodies, strange, anthropomorphic cities, surreal forms of transport, and spooky landscapes seem both unintelligible, and also shot through with a sort of intuitive, recognisable sense of rightness.

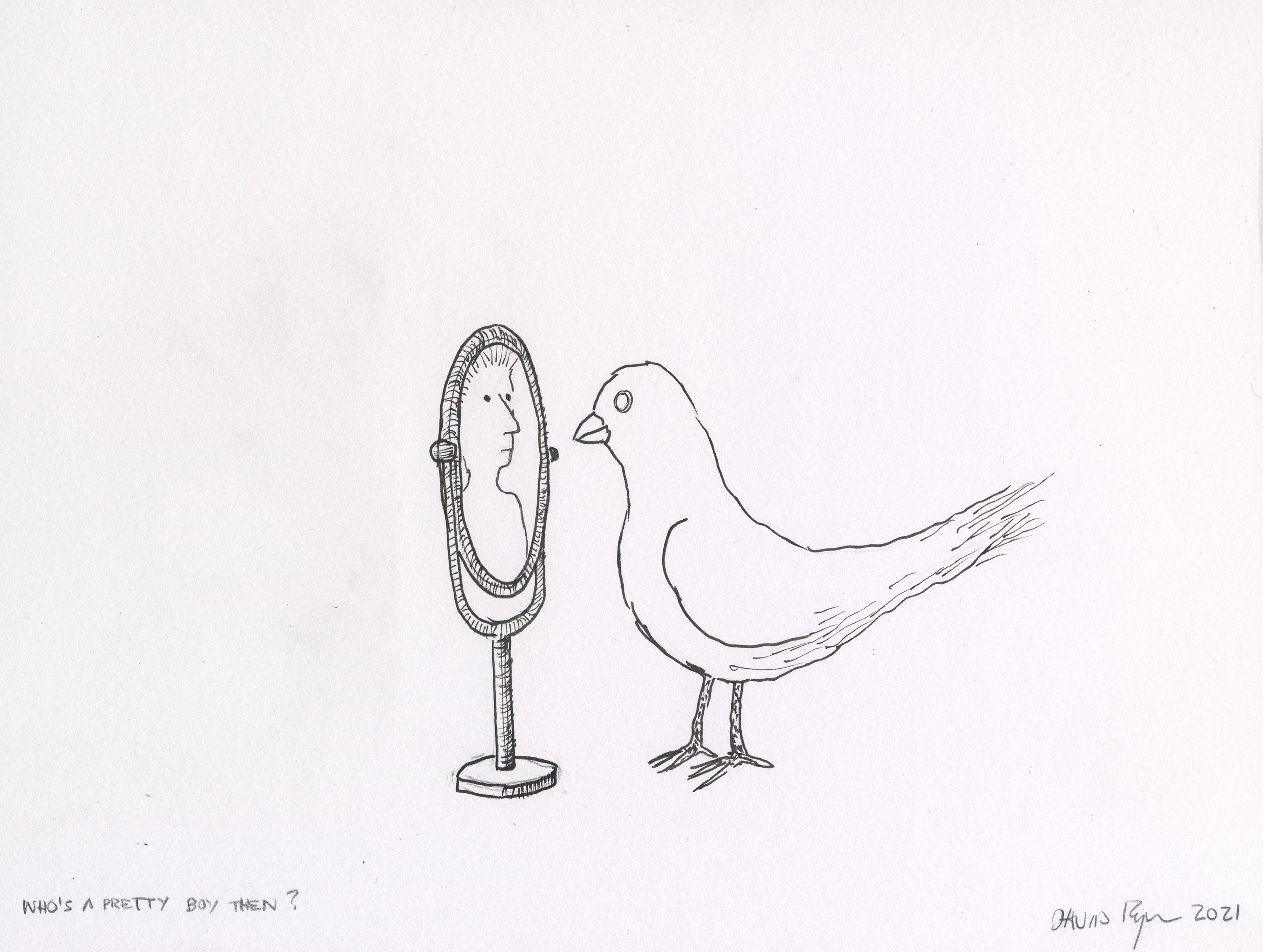

David Byrne,

Who's a Pretty Boy

Then

,

2021,

fadeproof waterproof

ink on archival paper.

9"

×

12" (22.9 cm

×

30.5 cm), paper

signed, titled, and

dated recto in pencil. © David Byrne, courtesy Pace Gallery

As the artist explains, he believes viewers may come across hidden or quasi-plausible connections in the pictures, and thus see things in a slightly different way. “In the dingbat drawings, they find them very familiar,” he says, “they're easy to relate to, but they're also kind of like, ‘Where in the world did that come from?’”

To follow this line of reasoning for yourself, take a look at Pace's content around the show here , also browse Byrne's work on Artspace and get a copy of A History of the World (in Dingbats) here.