Particularly within the context of social media, debates over censorship and representing the nude female body have been hotly debated. The "Free the Nipple" campaign, for instance, contests Instagram's policy that prohibits users from uploading photos that contain an exposed nipple (specifically, a nipple belonging to a woman, and not a man). Protestors criticize the policy as indicative of a larger problem: that policies and norms governing how women represent themselves are problematic when they're determined not by said women, but by others who sexualize and fetishize women and their bodies. The censorship of body parts also has an affect on the LGBTQ community... Last month, Artspace interviewed Gio Black Peter about, among other things, an exhibition he curated of images that had been censored on social media; Peter argues that censorship is especially detrimental to queer communities that rely on user-generated media to represent them, since they're less likely to see their cultures represented by mainstream media.

Meanwhile, while women and other marginalized groups often come under pressure to conform to certain beauty and physique standards, they catch the backlash of a double-edged sword when they celebrate their own beauty. If anyone knows what that's like, it's the late artist Hannah Wilke—whose never-before-seen Gum in Landscape (1975-76) photographs are currently being debuted at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Wilke is often credited with being the first artist in the women's liberation movement to explicitly depict a vagina in art. In the '60s, she made terra-cotta sculptures of vulvas—a body part that would recur throughout her career. Her most known work is likely her 1974-75 S.O.S. Starification Object Series; the artist models for the camera topless, mimicking feminine poses typical of "pin-ups" and glamour magazines. Stuck to her skin are wads of gum, each one sculpted into the shape of, you guessed it, a vulva. Wilke's portraits present her body as an object for viewing while simultaneously presenting Wilke as an active agent in her own objectification. Her aim was to explore the complicated and burdened relationship women have to media, stereotypes, and the male gaze. The series turned heads, but not necessarily for the right reasons.

Hannah Wilke, S.O.S. Starification Object Series , 1974. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright: Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at ARS, NY.

Critics lambasted the project for being "narcissistic;" because Wilke was conventionally beautiful, argued some critics, her nude photographs played to the male gaze and distracted viewers from gleaning any deeper meaning in the work. Art critic Ann-Sargent Wooster wrote, "The problem Wilke faced in being taken seriously is that she was conventionally beautiful and her beauty and self-absorbed narcissism distracted you from her reversal of the voyeurism inherent in women as sex objects. In her photographs of herself as a goddess, a living incarnation of great works of art or as a pin-up, she wrested the means of production of the female image from male hands and put them in her own."

But in the 1990s, Wilke was finally able to prove that her self-portraiture was not simply a narcissistic pursuit—though the circumstances were quite tragic. Wilke contracted lymphoma; she later died at the age of 52 in 1993. But in her fight with the cancer that ravaged her decaying body, she continued to photograph herself nude. No longer able to use her conventional beauty as a reason to dismiss the work, previously held criticisms were brought to task. To this Wilke said, "People give me this bullshit of, 'What would you have done if you weren't so gorgeous?' What difference does it make?... Gorgeous people die as do the stereotypical 'ugly.' Everybody dies." Hell yeah.

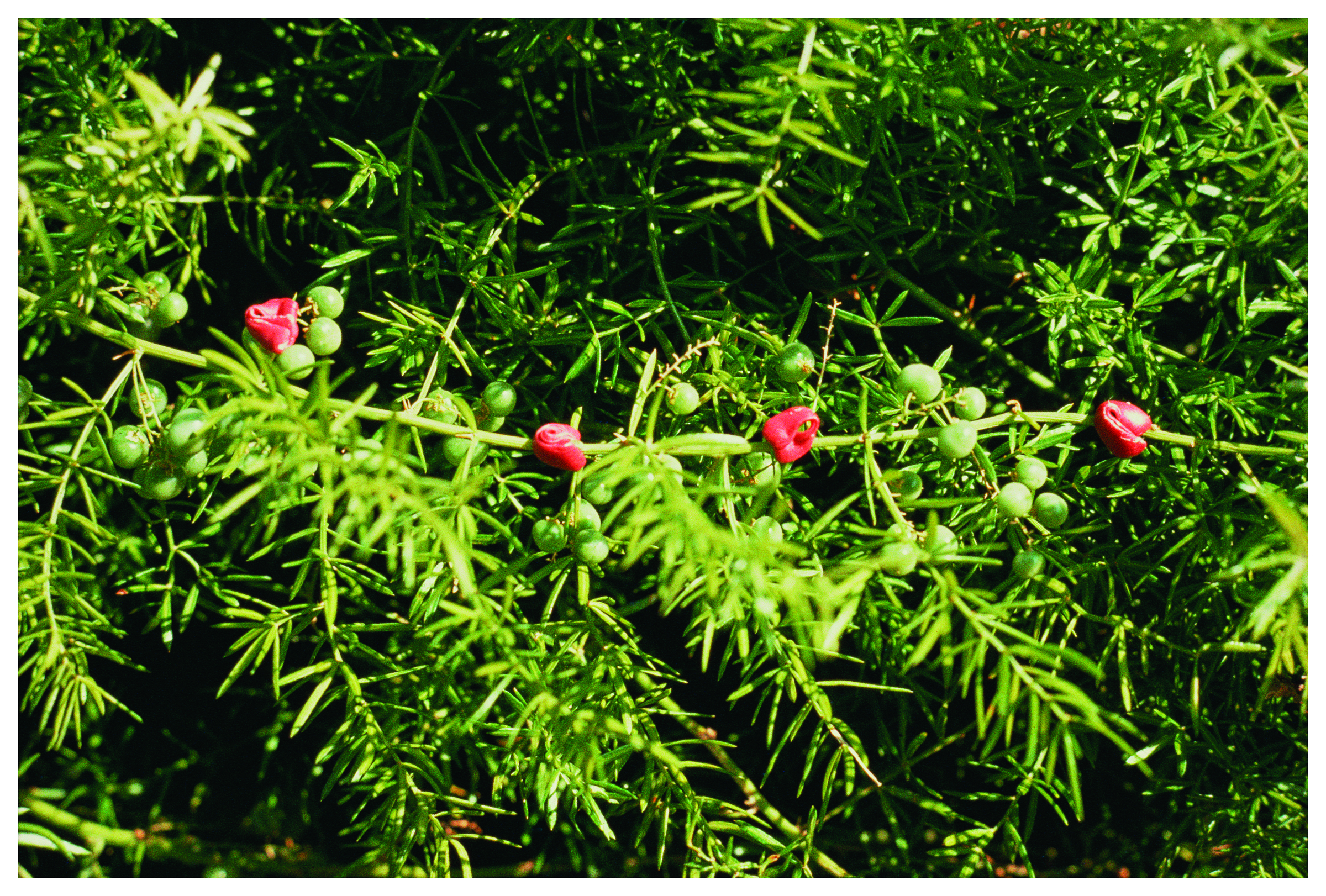

Since Wilke's death, much of her work and archival materials has been managed by her sister, Marsie Scharlatt, who just last year, made an astounding discovery. She, for the very first time, printed images from a group of Cibachrome slides that had never been visible to the public. The photographs contained within those slides, which of course where never seen or exhibited during Wilke's lifetime, are now on view at Tyler School of Art, and oh my god are they gorgeous. Once again using chewing gum as a sculptural material to represent the vulva, Wilke had made temporary sculptures using the landscape as substrate. "I chose gum because it's the perfect metaphor for the American woman," Wilke once explained. "Chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out, and pop in a new piece."

According to the exhibition catalog: "Wilke's composition challenges classical conventions of the natural landscape... Wilke's engagement with the landscape accounted for a centuries-long cultural patrimony of nature personified as female. With the extensive Gum in Landscape series of photographs, the vulvar sculptures therein uphold both of the metaphors of woman as nature and woman in nature. Wilke confronts the legacy of the beautiful, picturesque landscape at once questioning but not always refuting the enduring relevance of her symbolic inheritance."

See he exhibition "Hannah Wilke: Sculpture in the Landscape" until July 12th at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. In the meantime, check out a sneak peak of Wilke's provocative, never-before-seen photos below:

Hannah Wilke, Gum in Cherry Tree , 1976 (From the California Series, 1976). Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Gum with Berries, 1976. From the California Series, 1976. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Gum with Grasshopper, 1976. From the California Series, 1976. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke,

Untitled, 1976

(Blue Gum on Tree Trunk, Los Angeles)

. From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke,

Untitled, 1976

(Blue Gum on Tree Trunk, Los Angeles)

. From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke. Untitled, 1976 (Gum on Palm Fronds, Los Angeles). From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Untitled , 1976 (Red Gum on Palm Trunk, Los Angeles). From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Untitled , 1976, (Gum on Red Flower, Los Angeles). From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Untitled , 1976 (Gum on Succulents with Wilke’s Shadow, Los Angeles). From the Gum in Landscape Series. Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Untitled , 1978. (Glazed Ceramic Sculptures on Fire Escape in Snow with View of Greene Street, NYC). Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

Hannah Wilke, Untitled , 1978 (Two Glazed Ceramic Sculptures in Flower Box on Fire Escape, NYC). Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Copyright Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS) NY.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Knit, Purl, Protest: The Radical Feminist Stitchcraft of Ellen Lesperance

5 Things To Know About the Late, Great, Carolee Schneemann

The New Surrealism: Contemporary Women Artists Against Alternative Facts