Bruce Nauman once said, “Art is what an artist does, just sitting around a studio.” The idea was that art could be anything, as long as it was done within a space dedicated expressly to art-making.

For some artists today, such spaces are no longer necessary. A studio might be a laptop computer in a shared office, or it might be an international conglomerate run by a jet-setting art celebrity. Yet the romance of the traditional studio—typified by the solitary painter working at his easel, or even a Naumanesque video artist pacing around the room—endures. Jonas Wood ’s detailed painting of his studio hallway, for instance, recently sold at auction for more than $500,000, a record for the contemporary artist.

In the midst of all this uncertainty about the studio, “In the Studio,” a pair of exhibitions at Gagosian Gallery in New York (through April 18) accompanied by a two-volume Phaidon catalogue of the same title , offers an authoritative history. In his half of the project, the Museum of Modern Art ’s chief curator emeritus of painting and sculpture John Elderfield assembles paintings of studios from the mid-16 th through late-20 th centuries. MoMA’s former chief curator of photography Peter Galassi , for his part, unearths similar examples in photography.

Below, a look at some standout studios as seen by their inhabitants.

JEAN-BAPTISTE SIMEON CHARDIN

Attributs du peintre

(Attributes of the Painter), c. 1725-27

Oil on canvas, 19 ⅝ x 33 ⅞ inches (50 x 86 cm). Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Helen Clay Frick. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Oil on canvas, 19 ⅝ x 33 ⅞ inches (50 x 86 cm). Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Helen Clay Frick. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

In this early still life, Chardin locates the essence of the studio; it’s not a room so much as a set of tools. He shows us bladders of pigment and a jar of binder, a roll of blue paper, a statuette of the type used in academic drawing, and a palette with an array of brushes. Chardin would go on to make larger, more sophisticated “Attributes” paintings that flattered the cultural interests of his patrons, but this work is more personal and process-oriented (note the colors on the palette, which seems to have painted itself.)

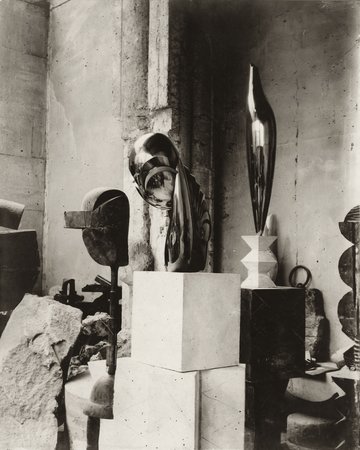

CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI

View of the studio: Plato, Mademoiselle Pogany II, and Golden Bird,

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches (29.8 x 24.1 cm). Private collection. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 x 9 1/2 inches (29.8 x 24.1 cm). Private collection. © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Brancusi’s Paris studio, now part of the attractions of the Centre Pompidou, attained mythic status even during his lifetime; Man Ray described visiting as “penetrating into another world.” Brancusi cultivated this mystique through photographs, offering densely layered, spatially confounding views of his sculptures and raw materials. Here he exploits the play of light on different surfaces, exaggerating the roundness of his metal sculptures while flattening out their wood, stone and plaster pedestals.

LUCIAN FREUD

Two Japanese Wrestlers by a Sink

, 1983-87

Oil on canvas, 20 x 31 inches (50.8 x 78.7 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. Restricted gift of Mrs. Frederic G. Pick through prior gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison. © The Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Oil on canvas, 20 x 31 inches (50.8 x 78.7 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago. Restricted gift of Mrs. Frederic G. Pick through prior gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carter H. Harrison. © The Lucian Freud Archive/Bridgeman Images. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

In a painting that’s uncharacteristically devoid of figures (unless you count the print of Sumo wrestlers along the upper edge), Freud reduces his studio to a single, crucial fixture. He had already included the sink in the background of his earlier painting Large Interior WII (after Watteau) ; its presence there led one critic to comment on “the sort of all-too-visible plumbing the English are prone to accept.” Freud’s focus on the sink, with its mildewy drain and trickling taps, may have been a retort to that review. But it also makes sense that he would fixate on an object with such psychosexual resonance, one that seems to make passing reference to Duchamp’s Fountain and to anticipate Robert Gober ’s sculptures.

JOSEF SUDEK

The Window of My Studio—Spring in My Garden, 1940-54

Gelatin silver print, 9 x 6 11⁄16 inches (22.9 x 17 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Anonymous gift. © Estate of Josef Sudek. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Gelatin silver print, 9 x 6 11⁄16 inches (22.9 x 17 cm). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Anonymous gift. © Estate of Josef Sudek. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

In photographs by Sudek, the artist's Prague studio is seen a space of ritualized confinement. His interior shots, such as Labyrinth in My Atelier (also in the exhibition), depict shelves heaving with books and papers. Even some of his views out the studio window feel mildly claustrophobic, affording only glimpses of a snowy garden through fogged-over glass. This springtime shot suggests the possibility of escape, but the oblique angle and the glass perched on the windowsill draw our focus back to the interior.

JASPER JOHNS

In the Studio

, 1982

Encaustic and collage on canvas with objects, 72 x 48 x 5 inches (182.9 x 121.9 x 12.7 cm). Collection of the artist. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Encaustic and collage on canvas with objects, 72 x 48 x 5 inches (182.9 x 121.9 x 12.7 cm). Collection of the artist. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Johns combines illusionistic painting, collage, and assemblage in this enigmatic canvas, one of the show’s many evocations of the display wall. The white background, with its little drips and splatters, looks as messy as an actual studio wall and seems to support various small artworks: three drawings, a sculptural cast, a wooden lath, and a propped-up painting, to be precise. But some of these objects are three-dimensional and others are merely trompe l’oeil; the result is a studio that holds out the promise of access to an artist’s inner sanctum, but in the end remains tantalizingly off-limits.