With a title sure to arouse nostalgia in Gen-X-ers, the group show “Come As You Are: Art of the 1990s,” at the Montclair Art Museum, takes a long, close look at the decade of Matthew Barney’s “Cremaster” cycle and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy spills.

Just two years ago the New Museum’s “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star” revisited a year of landmark exhibitions, culling works from the Whitney’s so-called “Political” Biennial and the robustly multicultural “Aperto” section of the Venice Bienniale. But “Come As You Are” is a rangier exhibition, with a longer timespan—actually 1989 to 2001, to account for the fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11—and an expanded map. “I wanted get away from New York, spread out a little,” says the show’s curator Alexandra Schwartz.

In her telling, '90s art isn’t defined only by the larger cultural trends of identity politics and globalization. The show spotlights some smaller but significant developments: the early days of Internet art, the ascendancy of Los Angeles as an art capital, and the first flickers in America of the European “Relational Aesthetics” movement. As Schwartz says, “It was the last moment before what was happening in the U.S. was very closely related to what was happening elsewhere.”

Artspace had a look at the show (which runs through May 17, kicking off a national tour) and picked out a handful of works that, we think, capture the essence of the '90s—and might change the way you think of the decade's continuing relevance in art.

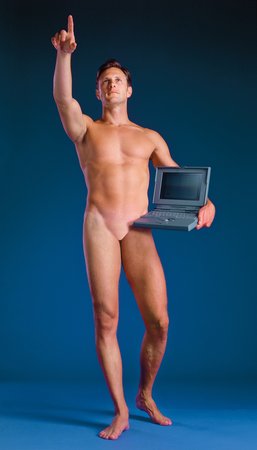

AZIZ + CUCHER

Man With a Computer (1992)

This image of a heroic yet neutered male nude with an early Mac laptop tucked under his arm graces the entrance to “Come As You Are” and the frontispiece of the catalog. The work of digital-imaging pioneers Aziz + Cucher, it was made in collaboration with a Silicon Valley photo lab. “Large-scale photography was so important at this time, and was becoming more and more enmeshed with digital technology,” says Schwartz. Although the work appears to celebrate innovation, it has a wry critical touch: the figure’s gesture, a nod to the fascist salute. The erased genitalia, meanwhile, anticipate Matthew Barney’s gender transformations (some two years in advance of the first “Cremaster” film) while also prefiguring the sci-fi speculations of today's DIS Magazine collective.

JASON RHOADES

Red (1993)

This sample of a larger installation was first seen in Rhoades’s 1993 solo debut at David Zwirner. It presents an unruly accumulation of small objects, linked mainly by their vibrant red hue—suggesting a DIY update on Matisse's Red Studio (1911)—and their associations with masculinity (pin-ups and beer cans are prominent.) Rhoades, who studied with Paul McCarthy at UCLA, would go on to become one of the most influential Angeleno artists of the '90s (a status recently confirmed by a touring international retrospective.) He was also a driving force in the messy, acquisitive category of installation known as “scatter art.” As Schwartz says, he “took the Duchampian readymade and pushed it to the limit.”

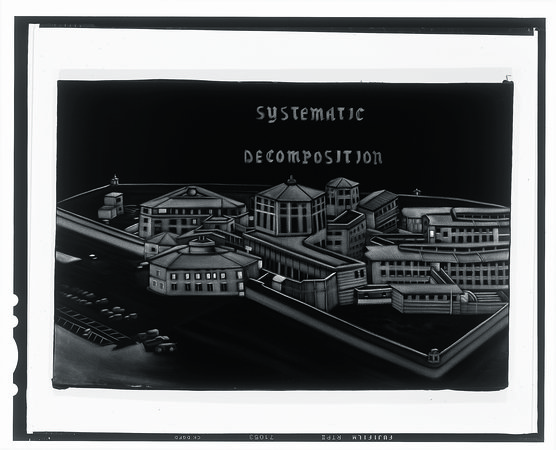

DANIEL JOSEPH MARTINEZ

Combined Action; Constructed Situation; Detournement; Systematic Decomposition (all 1993)

Daniel Joseph Martinez has long been associated with his interactive project for the 1993 Whitney Biennial, a series of buttons handed out to museum visitors that read, “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white.” The same year, he made these provocative paintings for the emerging-art “Aperto” section of the Venice Biennial (which are being exhibited for the first time since that show). Painted in a photorealist style on black velvet, they document the arrests of members of an Italian Marxist-Leninist terrorist group called the Brigate Rosse (aka the Red Brigades). One might see this series as an homage to Gerhard Richter’s painting cycle October 18, 1977—only in the kitsch manner of Velvet Elvis. “He got so much attention for the buttons at the '93 Biennial, but it was just a small part of what he was doing at the time,” says Schwartz.

ALEX BAG

Untitled Fall ’95 (1995)

In this episodic video, made while she was a student at Cooper Union, Alex Bag deftly satirizes art-school types and assorted pop-culture personalities. Donning wigs, playing with puppets, and spouting narcissistic monologues, she appears destined for YouTube celebrity; in 1995, however, the birth of the video-sharing behemoth was still a decade away. “Her teachers were some of the video pioneers from the '60s and '70s, and she felt that what they were doing was so different from what she wanted to do because she grew up in the '70s and '80s watching TV,” says Schwartz. “She was doing something which seemed so contemporary at the time, and now seems quite ahead of its time.”

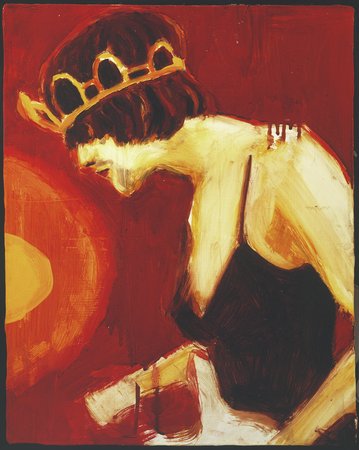

ELIZABETH PEYTON

Princess Kurt (1995)

This glowing red-orange portrait of a stagelit Kurt Cobain in drag belongs to a series of paintings of the Nirvana frontman, all made in the months immediately following his 1994 suicide. Peyton’s wispy portrayals of moody young men were already well known in the art world following her 1993 Armory Show appearance, but in Cobain she found an intensely charismatic subject with a tragic relationship to the media imagery that often served as her source material—in a way, he became to Peyton what Marilyn was to Warhol. “Popular culture was becoming this rabid machine, with reality shows and gossip magazines and especially the Internet,” says Schwartz. There’s a haunting sense of complicity in the otherwise straightforward elegy of Princess Kurt, an admission that Peyton and other artists are part of the machine.

SHARON LOCKHART

Untitled (1996)

“He is such a '90s-looking guy—you can imagine him being in a band,” Schwartz says of the skinny, slightly disheveled, androgynous subject of this image. Made by the Los Angeles-based photographer and filmmaker Sharon Lockhart—who emerged in that city alongside Laura Owens and Frances Stark—the work evokes the era in other ways: as an example of the decade’s large-scale color photography, or a subtle nod to globalization (via the generic hotel room that appears in reflection.) “It’s indicative of this flattening of the world, where you could have a Hilton in Dubai or Tokyo or Indiana and it all looks pretty much the same,” says Schwartz.

MARK DION

Department of Marine Animal Identification of the City of San Francisco (Chinatown Division) (1998)

This imposing installation is being shown for the first time since Dion’s 1998 exhibition at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, which had commissioned him to make art about the city. The piece looks like the office of a research biologist, but like most of Dion’s science-minded projects it reveals strains of institutional critique. The neatly labeled jars of specimens—which the artist in fact gathered from the fish markets of San Francisco's Chinatown—seem to invite comparisons between the natural sciences and the field of art conservation, while simultaneously functioning as a quirky taxonomy of nature in the urban landscape. “It’s not really clear what the work of art is,” says Schwartz. “Is it the act of doing the research and categorizing the fish? Is it the room? Is it the fact that the room is in the museum?”

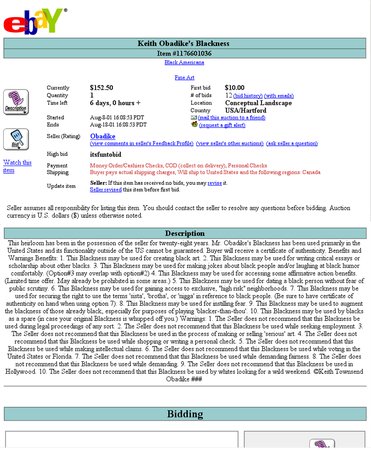

MENDI & KEITH OBADIKE

Blackness for Sale (2001)

One of the latest works in the show, this website intervention by the married couple Mendi and Keith Obadike combines Internet art and identity politics. Posting on eBay, which was then only a couple of years old, the Obadikes attempted to auction off Keith’s “blackness” (prompting many discussions about race). “It was one of the earliest things to ‘go viral,’ Schwartz says, noting that eBay removed the post after four days but dialogue about the work continued—at least, until the events of 9/11 eclipsed all other topics of conversation. Although it’s not strictly a '90s piece, “Blackness for Sale” is, as Schwartz says, “a great bookend to the show” and a work that resonates today.