Massimiliano Gioni's exhibition for the 55th Venice Biennale, "The Encyclopedic Palace," is that happiest of things: a staggeringly ambitious undertaking that has been beautifully realized and immediately acclaimed, bound to inspire other biennial curators to contend with its innovative approach.So what is that approach, exactly? Call it the Gioni Method.

Unlike most curators of massive group shows, who tend to bring together loosely tied agglomerations of exciting artists in an attempt to take a snapshot of their current moment, Gioni, an associate director at the New Museum, has been fine-tuning a novel format of exhibition since his 2010 Gwangju Biennale that begins instead with a thoroughly researched thesis and then sets out to prove it through a range of objects, many of them artworks and some of them not (books, documentary materials, etc.). In "The Encyclopedic Palace," the thesis seems to be as follows: life is mysterious and unknowable, but secular humanism and art present myriad ways of engaging with the world around us, and their consolations are largely sufficient.

It's an unusually upbeat and earnest show as a result, weaving artists and non-artists of all kinds—some terrifically accomplished and successful, some of them outsider artists who lived in institutions or on the fringes of society—into a beautiful tapestry of common, questing humanity. Gioni's layout is masterful, too, having tamed the gargantuan Arsenale (with the help of architect-to-the-art-stars Annabelle Selldorf) and made the best of the knotty warren that is the Giardini. Considering the significance of the show, however, it's worth lingering over a few of its novelties to consider how the parts meshed together. Here are four observations.

OUTSIDER ART IS IN, BUT STILL VERY ODD

The most notable aspect of Gioni's show is his inclusion of work by many outsider artists, ranging from mystics like Hilma Af Klint and Aleister Crowley ("self-proclaimed prophets," in the curator's words) to asylum patients like Shinichi Sawada. It's a fascinating element, expanding the field of art beyond the professional circuit and into an examination of Art itself— but, as is always the case with outsider art, it's complicated. For one thing, when seeing so much of it in once place, it's hard not to notice that there are certain commonalities between the work of many such artists—tightly filigreed drawings that evince a desperate need for control, say, or portrayals of unusual sexual fantasies—that suggest somewhat redundant pathologies rather than visionary thinking.

Other works, like a series of model houses obsessively built by the Austrian clerk Peter Fritz (credited as the artwork of Oliver Elser and Oliver Croy, who discovered them in a junk shop), are less pieces of visual art than object lessons in the weirdness of the human mind and our pursuit of meaning in the world. By including these works, Gioni makes much of the show into an investigation of the psyche—particularly in the Giardini, which is organized around Carl Jung's hermetical Red Book as a focal point—and this, above all, proved challenging for visitors hoping for the traditional biennial experience of seeing a lot of impressive art. That's not to say that there weren't outsider pieces with plenty of visual pizzaz to spare, including works by Sawada, Arthur Bispo do Rosario, and Carol Rama, the Shaker gift drawings, and the anonymous Tantric drawings.

LIKE AN ENCYCLOPEDIA, THE SHOW NEEDS TO BE READ

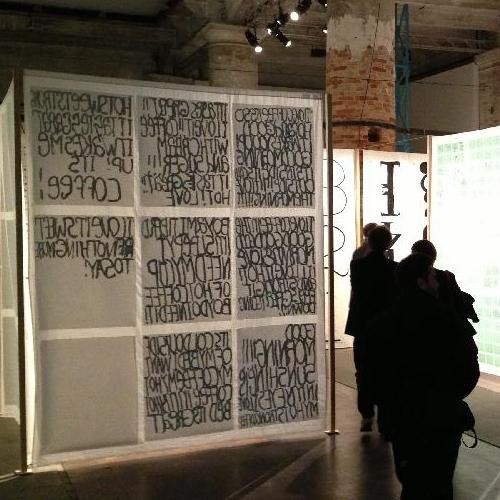

In the Golden Lion prize ceremony, Gioni mentioned that his show has "100,000 words of wall text," and he wasn't kidding—the labels accompanying each work in the show are lengthy, wonderfully written, and critical reading for anyone who wants to understand the show. In a helpful format, each placard is divided into two parts, with a brief bio of the artist at the top and then background information about the specific work included in the show. As a result, visitors make their way through the exhibition as readers as well as viewers, and this is a core element of Gioni's curatorial style—each piece is scrupulously fitted into an overarching pedagogical narrative, and anyone who wants to understand the show's thesis needs to follow these syntactical threads.

This is a very effective way of imparting information, and few viewers who follow Gioni's textual breadcrumbs will emerge without understanding the show's thrust, but what it gains in clarity it loses in interpretive latitude. Most artworks, after all, are ambiguous, containing a range of possible readings and emphases, and this model of pinning the works down like scientific specimens necessarily curtails their liveliness to a degree. This is yet another way that Gioni's show differs from your average biennial, where works are typically given ample room to breathe, losing some clarity as a result.

I'M OK, YOU'RE OK

Venice Biennale commissioner proudly described "The Encyclopedic Palace" as "a message of hope" and a call to "build your own encyclopedic palace," and indeed the show is a feel-good affair, presenting many possible paths to being actualized human beings (or whatever the best thing is people can achieve in a secular universe). Gioni noted in his speech that there's a "melancholy note" in the show, because so many of the visionary and mystical efforts by individuals in the show "failed," such as Marino Auriti's attempt to construct a $2.5 billion skyscraper on the Washington Mall to house all of human knowledge in his namesake Encyclopedic Palace. But that's not entirely true, since the show suggests many twists on the old it's-not-the-destination-it's-the-journey philosophy, according to which everyone should just "do the best you can," as Auriti wrote as one of the inspirational maxims he hoped to etch around the base of his palace. (Next to it he wrote, somewhat humorously, "use the scale for each thing.")

This uplifting message, central to the humanistic thinking that emerged during the Enlightenment, runs through the show, which treats religion as an object of secular fascination rather than faith—see Danh Vo's Vietnamese church (a commentary on colonialism), a Francis Bacon-esque sculpture of the pope by Miroslaw Balka, and amused videos by Harun Farocki, Camille Henrot, and João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva. Death, however, is largely treated as an unfathomable inevitability that it's best not dwell on too much. (The cold, hard fact of death rears its spooky head rarely in the show, as in Kan Xuan's terrific wall of videos documenting every one of China's imperial tombs and the death mask of Andre Breton.) For a truly encyclopedic show about the human condition, that seeems to be a gap.

ANY BREAKOUT STARS?

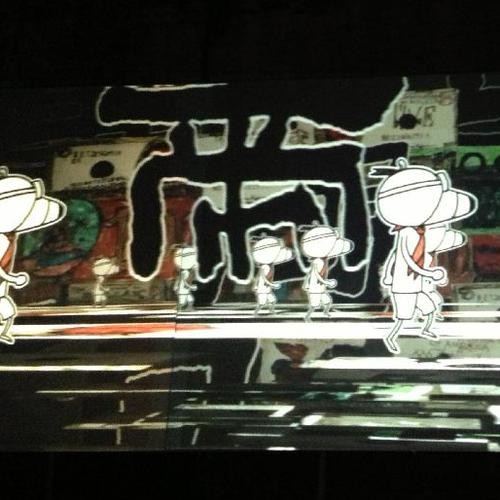

Yes. While the show had less in common with an art fair than usual—and collectors do treat the Biennale as a place to compile shopping lists—there were a few young and mid-career artists whose star turns ensure we'll be seeing much more of them in galleries and museums these next few years. Camille Henrot, this year's Silver Lion winner, was a word-of-mouth favorite even before her victory, with her video channeling anthropological research through Internet-age vernacular and hip-hop emerging as an important, of-the-moment touchstone. (Oddly, with the exception of Uri Aran's splendid mixed-media piece employing a online-chat-based projection and Ryan Trecartin's confused installation awkwardly placed toward the end of the Arsenale, there was little other art that tackled the Internet or social media—with the partial exception of Nadar's 19th-century aerial photographs of Paris that look like shots from Google Maps.)

Also to watch for are Matt Mullican, whose mini survey in the show cried out for a full museum show; Imran Qureshi, whose lovely updated Persian-style miniatures have landed him a current show on the Met's rooftop, as well as a survey at the Deutcshebank Kunsthalle; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, the Turner Prize-nominee whose chiaroscuro-laden portraits could also be found in Victor Pinchuk's Future Generation Prize show; João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva, whose literarily rich videos of invented religious rites compelled lengthy viewing; Neïl Beloufa, whose video of men in Mali telling stories mixing fact and fiction in the glow of handheld fluorescent lights was lushly eerie; Ragnar Kjartansson, who doesn't really need any help at the moment, reputationally speaking, but whose S.S. Hangover performance once again pulled off his trademark combination of beauty and pathos; and Sharon Hayes, whose intellectually acute and sociologically penetrating video of women speaking candidly about their personal lives won a special mention from the prize committee.

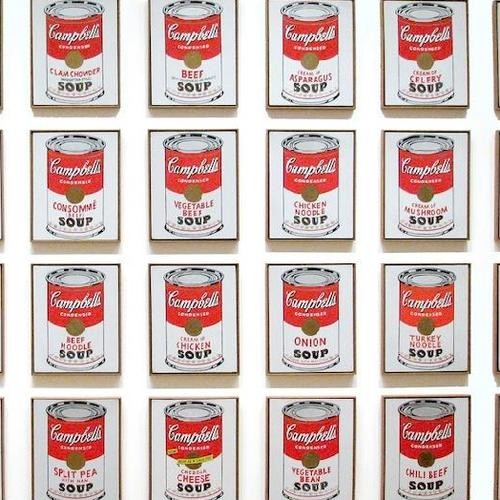

At right find a selection of works from our Venice Biennale: "Encyclopedic Palace" Collection

RELATED LINKS

Q&A: Massimiliano Gioni on His Venice Biennale, and "Trying to See More"

Analyzing the Golden Lion Wins