The Venice Biennale is often called the Olympics of the art world, and just as politics and national identity are a barely concealed subtext during that international athletic contest, the Biennale is a often a stage for countries and the artists they choose to represent them to make statements about how they want to be viewed by the rest of the world. As a result, looking at the pavilions through the lens of politics can be irresistible.

Nowhere in the Biennale is the nationalist subtext more bluntly conveyed than in the Chinese pavilion. In fact, the art seems to have been chosen to prove a nationalistic thesis: China has an astonishingly rich cultural history, it has absorbed everything it needs to know about Western art, and its artists are employing the most cutting-edge technology to take art to the greatest heights mankind has ever seen. This is stated pretty clearly in the wall labels written by the curator, Wang Chunchen, a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts China and an adjunct curator at the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum.

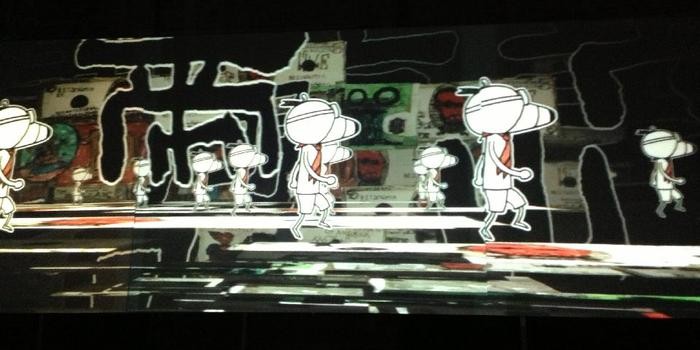

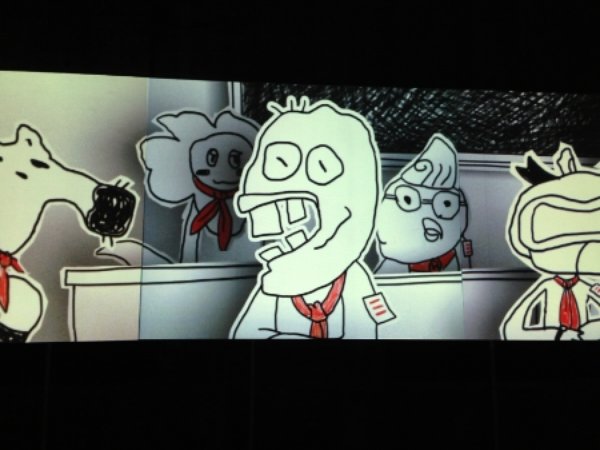

Zhang Xiaotao has two videos in the show, the better of which, The Adventure of Liang Liang, is a short black-and-white film, rendered in impeccable 3D animation, about a young boy fleeing from his cartoonishly scary school teacher and running around through a fantastical world. According to the wall text, Zhang Xiaotao's art is emblematic of "the contemporary advantage and possibilities of the virtual art," and the artist himself "demonstrates the multiple possibilities and the practical abilities of a Chinese artist." The text continues, "Chinese artists should contribute to the area of new media art, it is an area with unlimited possibilities and potential of development."

In Wang Qingsong's Follow Him, a caricature of a frazzled scholarly figure (representing the artist himself) sits amid stacks and stacks of books—many of Chinese history, some of Western art and fashion history (including several tomes on Warhol)—surrounded by crumpled-up wads of paper, as if he has been trying to unify the two strands in vain. But will he fail at this alchemy forever?

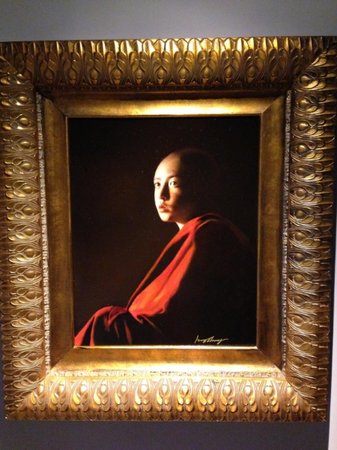

In a group of paintings by Tong Hongsheng, the artist applies the techniques of Vermeer—universally acclaimed as one of the greatest painters in Western art history—to traditional Tibetan Buddhist subjects, an intriguing twist considering that whole political can of worms. The main point, however, seems to be that Chinese artists can do Vermeer, too.

The culmination of the pavilion is at the end, where Miao Xiaochun has projected The Last Judgement in Cyberspace, a digital interpretation of Michelangelo's Renaissance masterpiece, another cornerstone of Western art history. To its right is a digital version of Titian's Flaying of Marsyas as well. Here's the wall text:

"Miao Xiaochun's work is the observation and interpretation of the history and culture from a contemporary perspective. It forms a viewpoint for Chinese artists to see the civilization of the world; not only has Chinese art examined and absorbed the essence of Western art history, but also presents the unique creativity of Chinese contemporary artists. It belongs to the kind of practice that would open up ancient and modern civilizations…. [The Last Judgement in Cyberspace] is also a reinterpretation of western art history, and it shows the worldview and the ability of control of a Chinese artist… it is no longer a purely religious scene; it becomes an image of a greater world that is based on the equality of all human beings."

In other words, it's even better than Michelangelo.

Click here to view more works from artists in the international event's national and para-pavilions.