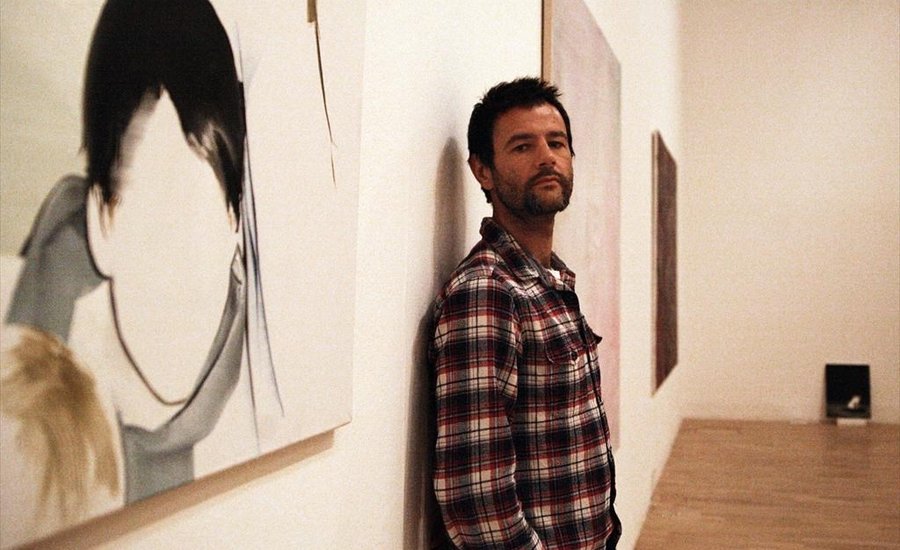

Wilhelm Sasnal’s paintings cast a critical eye upon bleak social realities and are illuminating anchors for those of us willing to confront the West's newly vigorous and highly disquieting proto-facist leanings. Born in Tarnów, Poland in 1972, the artist lived through the bleak reality of the Soviet Bloc’s fall; his oeuvre is a reflection of both those tumultuous times as well as our current and very eery political climate.

Primarily as a painter, but also through film-making, print-making, drawing, and photography, the artist digests and reinterprets a visual language of the banal; his images are derived from advertisement, mass media, pop culture, personal snapshots, and the Polish landscape. Through a purposefully deskilled minimalism, Sasnal comments upon the symptoms and ills of war, propaganda, capitalism, consumer society, and the hyper-normalization (see Adam Curtis’s recent interview here ) of unrealities spread by corrupted governments. His career was shaped by the re-emergence of figuration in painting in 1980’s Europe which birthed the likes of Neo Rauch , The whole new Leipzig School and YBA artists like Tracey Emin . After inclusion in 2002’s Art Basel, Sasnal’s career began a rapid ascension. He received the top ranking in Flash Art’s 2006 listing of the world’s best young artists, was a fellow at the Donald Judd mecca Chinati in Marfa, had a major exhibit of 60 works covering a decade of his career at Whitechapel Gallery in London, and solo-exhibitions and at Anton Kern and Hauser & Wirth in New York. His work now resides in the permanent collections of not only major institutions like MoMA and The Guggenheim , but also with a who’s who list of contemporary collectors.

Now is the perfect opportunity to consider the artists own words, excerpted here from the painter's interview with curator and critic Andrzej Przywara in Phaidon’s monograph Wilhelm Sasnal .

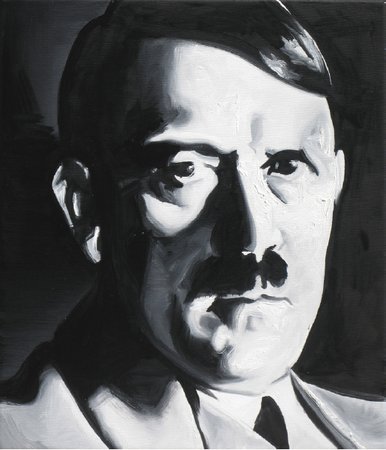

You recently sent me a text message with a portrait of Hitler. What made you paint him?

It came out of my cooperation with the organization Never Again. Being anti-fascists, they started a campaign to get Nazi memorabilia removed from (Polish auction website) Allegro. I joined in because I see (selling Nazi memorabilia) as a way of sustaining that legend, that tradition. But I wondered what would happen if I painted Hitler. What would the repercussions be? Is painting always a tribute? Later, I wondered what it means to think about Hitler’s face for two hours: is it time spent with Hitler?

Untitled

, 2010

Untitled

, 2010

Like reading a biography of Hitler?

Exactly. It’s a kind of analysis. I had always laughed at stories about how painters get into a person to show their inner condition in a painting. But now I realized that’s sort of what I’m looking for when I paint. To see Hitler. To find out who Hitler is. But it’s not knowledge that can be expressed in words.

Were any emotions involved when you were painting?

There was the question, “What am I doing?” If there were any emotions, it was this sense of “Am I complicit?” I thought about the people who drew, worked in the camps as illustrators, all those who painted. They had people in charge of culture and entertainment there -- musicians, artists.

Did you want to paint a psychological portrait?

I had two photos I had come across online. I don’t even know what year they were taken. In one of them you see all the evil in him. The other is a portrait of a man lit from the side. Just a normal man. It’s not a sinister photo. The evil photo was too much for me—I gave up. I couldn’t paint Hitler that way, so I ended up painting him as a normal human being. It was important that it be a photorealist painting—I didn’t want to turn it into a caricature.

You once painted the man who had been the director of Azoty (a nitrogen plant in Tarnów) in the 1920s. He looks like Hitler.

But that was a coincidence. He simply looked that way. My wife Anka’s grandfather still wears a Hitler moustache. They’re old-timers— I guess that must have been the fashion in their day. What’s interesting is that there’s a scene in Aleksander Ford’s 1948 film Ulica Graniczna (Border Street) in which this collaborator, a Polish innkeeper, grows a Hitler moustache right after the Germans invade.

Artur Żmijewski once did a series of exhibitions called "Parteitag" (1997-99). He asked artists to contribute pieces made from another vantage point, to try and place themselves in the role of the oppressor instead of the victim. He wanted them to take the side of evil and try to make their statement from that perspective. To give up their comfortable, privileged position.

To stop hiding behind it.

—because painting gives you that option.

Of course. Good thing it isn’t a performing art, that you don’t have to go on stage and show your face. My sense of evil is strongest when I take my camera and go out in the country. I feel calculating then.

Because you’re spying on real life?

There’s something condescending in the way you look at those people. It’s like the interviews Lanzmann did with Polish peasants for Shoah (1985). You don’t even have to film the people, just their barnyards: the manure, the squalor, the filth, the drunkenness, etc. It takes place at so many levels. There’s this film, Hitler: The Last Ten Days (1973), about Hitler in the bunker. I remember talking about it with Ulrich Loock. He was very agitated, he said. What bullshit—all the evil is blamed on one guy, but there were hundreds of thousands of people who were involved. They supported it all and were just as evil as he was.

Did you paint anybody of similar stature recently?

Yes—Churchill and Adenauer. There’s a debate going on about declassifying files concerning Eichmann’s escape, in which he was helped by the Catholic Church, the German government and America. I read that one of Adenauer’s aides had served in the SS. It all flows together like that. Hitler’s not an isolated character. I don’t want to make it sound relative, but what allows me to paint Hitler today is partly the time that’s passed since the end of the war. It’s been seventy years. Painting Hitler today is like making comedies about World War II.

Churchill

, 2009

Churchill

, 2009

Is it a comical situation, then?

I don’t know. A little comical, a little risky.

Owing to the state’s historical policy, these things still arouse emotions in Poland. Paweł Althamer made this children’s coloring book for the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising, called Commanders of the Campaign. Alongside portraits of the generals who commanded Polish troops in September 1939, there was also a portrait of Hitler. The Museum turned down the project because it didn’t want kids coloring Hitler’s face. The coloring book didn’t distinguish between the good guys and the bad guys. They were all mixed together.

Remember how someone in Berlin destroyed a wax effigy of Hitler? It’s kind of like a Renaissance painter painting devils, like Memling when he painted devils. We’re talking about this portrait of Hitler as if it were unrelated to anything. But Memling could paint angels as well as devils.

Does that mean you can paint anyone you like?

It’s a question of taste. That’s how I see it.

So whom do you paint?

Sometimes it’s a matter of chance. I can paint people I don’t even know simply because I liked their photo. Because of their faces. There are no rules. I might have crossed the bounds of good taste with the portrait of Hitler. In the three days I spent working on it, the name Hitler was mentioned twice on the radio, which was playing in the background. That individual is still present in stories, in language. That’s why I feel completely exonerated.

Untitled

, 2010

Untitled

, 2010

What about the swastika you drew for Never Again? One of its arms is shaped like a penis.

I did that on purpose, to discredit the swastika, to show how dick-headed it is.

The swastika’s floating over this landscape. It casts a shadow over it. The dick is practically touching the ground.

I wanted to convey the message that the swastika is impotent, that it’s something lame that I wouldn’t want to identify with.

Do you want to identify with strength?

It doesn’t matter what I want to identify with. The Nazis are the ones who identify with strength. I wanted to show the weakness they cover up with their swastikas. And I wanted to see what it’s like to draw a swastika.

You draw a dick-headed swastika and turn it into an anti-fascist poster.

It’s a pop thing, yes.

But then you go back to your studio and start working on a portrait of Hitler.

Collaborating, you mean?

Well, yes. Are any paintings fully abstract?

There are paintings that look abstract, but they never really are. That’s the way I think about my paintings. I’d never do an abstract painting . There was always a connection with reality.

But what is that connection—a specific story or just an emotion?

Sometimes it’s just an intimation, an emotion. I’m thinking of photophobia here—the fear of light. I tried to paint a light that would make me squint. That’s how I imagined it. When I look at the sun and close my eyes, there’s this orange after-image that comes out abstract in the painting, but it’s not an abstraction.

But photophobia has an element of fear to it—

Revulsion, rather.

—yet painters are always afraid of losing their sight. You’ve given two interesting examples, one where you don’t see because you’re blinded by light, the other where you don’t see because your eyes are shut. Do you paint out of fear?

No. Sometimes I realize that I’m doing something—and this doesn’t only apply to painting—in order to dull some fear. It’s completely irrational. But I now recall that one of the pioneers of animation went blind because he wanted to discover the nature of afterimages and looked into the sun for too long.

There are works by Władysław Strzemiński 3 in which the physiology of seeing is brought out in the painting, which looks abstract but is actually an afterimage of landscapes, lines and abstractions.

With hindsight, I realize that I believe in the poetic nature of the phenomenon, but I don’t entirely agree with the Theory of Seeing Strzemiński developed based on his analysis of Cézanne . It doesn’t really matter much in art.

What interests people nowadays is that he was one-armed and one-legged, and that his wife used her own sculptures as firewood.

On the other hand, there’s something that puts him in the limelight, that doesn’t allow him to hide behind his paintings but makes his personal story come out.

It’s the same with Andrzej Wróblewski. You said the propaganda aspect of this work interested you.

It doesn’t interest me that much. It’s just something I notice.

Wróblewski insisted that paintings are not just about the act of painting but that they have something important to say.

Of course they have something to say, but how many people do they speak to? I don’t believe that art has the power of propaganda. Art doesn’t change the world. That’s why I respect and understand what Artur Żmijewski says, but I don’t share his opinion.

But art does change the world—like when an architect designs the Palace of Culture.

Granted—architecture does change the world, cinema changes the world, literature changes the world, but painting has a much smaller blast radius. It matters, but on a micro-scale.

What about Jan Matejko’s The Battle of Grunwald (1875-78)?

That was painting before the invention of cinema.

Painting changes our way of seeing the world. Painting has a commemorative form, it can be involved in politics. Take the series of paintings Richter devoted to the Baader-Meinhof group (October 18, 1977 (1988)). It sparked a huge discussion. In a way, that series made an impact on society. It was a statement. It seems that some of your paintings are also seen that way—when you did the Art Spiegelman paintings, for instance (Untitled (Maus) (2001)). Everything that involves the experience of a generation, that’s one way painting can change the world. What do you think?

Yes, but those were isolated cases. Consider the debates around films and compare them with debates about painting.

You mean it’s a question of impact?

Yes. Painting can change the way you, I and five hundred other people nationwide see things.

Bathers at Asnieres

, 2010

Bathers at Asnieres

, 2010

What is your painting committed to?

It’s not committed to anything. That’s what I think. Today I wouldn’t do a painting like the one with Anka and Patrycja titled Anka doesn’t vote and Patrycja’s stopped eating meat (2001). I see painting differently. I don’t think it’s the best medium for conveying the obvious. You’re asking whether my painting is committed—if it is, it’s not in a conscious way, or in a way I only become aware of when painting. I often realize that my views were behind my decision to paint something, but it’s never intentional. My critical attitude to something doesn’t make me paint the way I do—that is, it does, but later, unconsciously. It’s different when I’m painting and when I’m doing drawings for the left-wing journal Krytyka Polityczna , or an engraving for Never Again.

Do you draw a line between one and the other?

Yes, I do—they’re two different things. That’s not painting.

Why did you call your show at Zachęta “Years of Struggle” (2007)?

I wanted to treat myself with a bit of detachment. Because I do struggle with painting. I wanted it to sound a bit absurd. It was meant to sound light, and not— as some understood it—to introduce an air of commitment and actual struggle.

War stories .

It was supposed to be free of war stories—exactly. But I wasn’t denying the gravity of the subject matter.

Right, so the paintings are committed to something after all?

Maybe I don’t understand commitment the way I should. It’s not about taking sides but about reminding people. If you understand commitment that way, then I am committed to recollecting history.

Swineherd

, 2008

Swineherd

, 2008

Recollecting? The phrase brings to mind a futile pursuit, like collecting trash. There’s a scene in your film Swiniopas (Swineherd) (2008) in which the protagonist goes over to a manure heap, pokes about in it with a stick, and digs out a plate decorated with a swastika. On the one hand he’s digging up history, but the poking around could be a stand-in for painting. That’s also whimsical because you’re saying you struggle with painting, but on the other hand it looks as though painting comes easily to you.

No. It’s not easy. I recently had the impression I was scratching them out instead of painting them. I can’t say anything about commitment because, if I do, then five sentences later I realize I’m being inconsistent.

You focus on many things at a time. You work on many different subjects concurrently. What were you painting when you were doing the Hitler portrait?

A winter landscape. I was also painting a woman sitting on a tuffet with a lamp covering her face. It’s like putting forward propositions. There are no rules. There are things that intrigue me. I can be wrong at times. Some paintings are a mistake. You do them because you have a sense that the topic’s important. I never assume something will be important. I paint because the potential motif of a painting seems intriguing. I imagine what will happen when it gets painted, that it will elevate its status. But I’m often wrong. My intuition tells me what I should paint. I don’t follow any program when working.

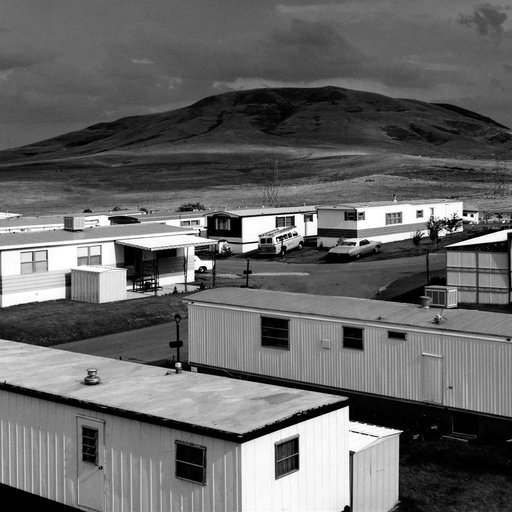

Flood in Moscice

, 2005

Flood in Moscice

, 2005

But you often refer to the war.

Well, yes, for me time is divided into what happened before and after the war. That history, as told by many works of art and many people, is very close to me.

Since we’re on the subject of before and after, I wanted to ask you about Tarnów, where you lived before moving to Krakow.

Tarnów brings back memories of childhood. Mościce, the district in Tarnów where we had a flat on the grounds of the Azoty nitrogen works. My mother grew up there, then I did, then finally Kacper, my son. He was six when we moved here, to Krakow.

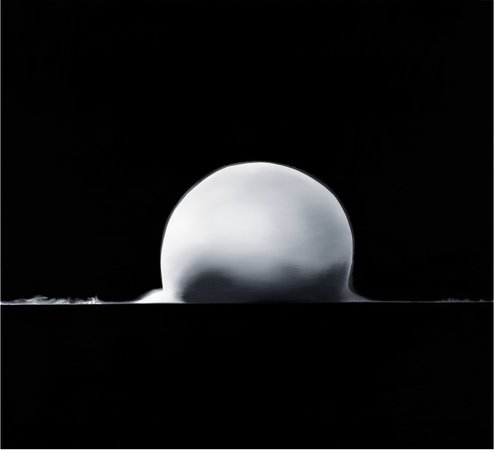

Fallout

, 2010

Fallout

, 2010

Your latest film ( Fallout (2010)), a post-apocalyptic image of the world, was shot in Tarnów.

I remember that apocalyptic mood from elementary school. It disappeared with the end of the Cold War, but I remember the real sense of threat. Mutually Assured Destruction, the arms race, moving warheads, Chernobyl—it was all hanging by a thread. They made films about nuclear disaster in the 1980s. One of them was The Day After (1983). I remember watching it with my mother. It was about a nuclear disaster in the States. It was an anti-war manifesto, of course, and I remember how the papers printed stills from the film: X-rayed human bodies with this skeleton. That shows how close the threat was. We were fed on that threat. There was a rumor that an American nuclear warhead was aimed at the Tarnów nitrogen works, because it was a strategic chemical plant.

Would you say that going back inside the plant with a camera is a return to your childhood and all those emotions?

I guess it is, partly.

Did they let you in there before?

Not when I was a child, but later, in secondary school, I had an apprenticeship there. It lasted a month. I remember the workforce was larger than it is today. It’s not very common to see anybody there now. Sometimes you see someone scurrying in the background. It’s empty. They simply need fewer people to do the job. I remember stories from childhood: What are you supposed to do if there’s an explosion at the works? If a cloud of chemical gas got released, you had to hang wet blankets in the window, because they would stop all the shit from getting into the house.

That’s what you were taught…

All the time. The PA system all over the district next to the works was, and still is, tested once a month to make sure people will be notified in case of an emergency, so it was kind of like living next to a nuclear power plant. This constant sense of threat.

Is making films like that fun for you? Making your childhood dreams come true, organizing reality?

When we’re thinking up the script it is, but later it’s just hard work—there’s nothing fun about it. Painting is like child’s play, not because it’s trivial or anything, but because it’s so comfortable and pleasant compared to making films.

In what sense?

Well, you go to your studio, you play music, and you either paint or you don’t. It’s OK if you don’t paint anything. There’s no obligation. There’s no one around you. You rely on yourself. Even if you screw up, nothing happens. You bear all the responsibility. But then again, what kind of responsibility does destroying a painting or doing a bad painting involve? Unless you’ve assumed you’re painting a masterpiece. [Laughs] Then you’re fucked. But I never make that assumption. Film entails a lot more responsibility. You have so many people around you, you’re spending money.

This film, which is set, among other places, at the Azoty nitrogen works, was first called "Love Supreme." Then you changed the title to "Fallout."

It began when I found a motel. I was riding my bike when I happened to stop next to the Krak motel, which looks a little like a blast site. It made me think of photos from Chernobyl. And that’s where the whole post-nuclear setting came from. We wanted to tell the story of a guy who falls in love in this horrible, psychedelic and sick situation. Maybe love is like a sickness. That didn’t work out, it fell apart at the screen-writing stage. Maybe we didn’t have enough critical distance. Later, in the editing room, it turned out that the abstract nature of the story and the landscape overshadowed our original theme of love as a psychedelic condition. It took us time to realize that what we had was the fallout or falling apart of relationships, purposefulness and life. There is no hero as such—everybody’s in the same position. That’s where the title Fallout came from. ‘Love Supreme’ had to do with the supremacy of love. It was about—

Domination?

Yes, about love being above all things. It wasn’t about hopes but about this psychedelic state. For me, a nuclear explosion isn’t just something threatening. It’s also a state of psychedelia, a transition, where reality is transgressed. I often thought I’d like to see an atomic explosion as a spectator. Like the first tests, when spectators were given glasses and watched the blast from a hundred kilometres away. I see it not only as a condition of threat but a transition into another state of matter. And naturally there’s the blast, which can blind you. Like looking into the face of God.

Such metaphors are very much like descriptions of perceiving the image in the process of painting. Is a completed painting a kind of fallout?

No, rather not. I paint nuclear explosions.

Untitled

, 2008

Untitled

, 2008

That’s how you see it?

Yes. At a metaphorical level. But the point is also that I’d be unhappy with the outcome if the fallout were to remain. I’d paint the canvas over, I’d tear it off the frame. The paintings I do, the ones I keep, aren’t fallout—they have a power of their own.

Y es, but you could also say that fallout has power because it’s radioactive.

Fallout is what you take away with you after seeing the painting. It’s something different still. We might be operating at some meta-level here, but I thought that the visual arts rarely move me; I’m moved by music or film. But on the other hand after visiting a gallery I keep something you could compare to fallout. I think about it later, and it’s like fallout in that way. Fallout of what I saw. I don’t have to go back to it or need to see it again, but it’s there, inside me.

Contemporary art typically makes use of fragments, of a fragmented, shattered world. One has no overview of the whole, but later it gets so infectious—

that you fit that element in somewhere. There’s a context where that element belongs. That context is in your head.

But I also meant that in "Fallout" there was a sense of futility, and painting is in a sense a futile activity—after all, how many paintings have you done?

You know, I thought quite seriously that it’s a hopeless situation. That’s what I thought about myself—how many paintings can you do before you lose your critical distance? There comes a time when you want to be the master of your own school. You aim for some impossible perfection. It’s all banging your head against a wall. That’s why it’s horrible if painting’s all you have.

What about Krakow? Is it your promised land?

[ laughs ] What nonsense. Krakow as the promised land. It might be for teenagers who realize they’re missing out on something by not living in a bigger city. If you’re from Tarnów, that big city is Krakow, because Tarnów’s always been in the shadow of Krakow. You move from a small town to a big city. We get Radio Krakow and Krakow TV in Tarnów, so you want to live in the city they’re broadcasting from. But now, the way I see it, I could just as well live in Tel Aviv! [ laughs ]

You’ve recently done a series of strange views of Krakow.

The social life in Krakow is real lively. I’m saying this a little ironically because it’s easy to drown in the alcohol sloshing about in the bars at night—and sometimes during the day, too. And that’s kind of what that series of paintings is about. When I moved back here from Tarnów, I told myself I’d be immune to the temptations of social life, that I’d be spending more time in Plac Centralny in Nowa Huta than around the Market Square, but that was nonsense. I soon came to like the nightlife after all the time spent in Tarnów, where family was the only company I had. And here it turned out I could return to the world I left when I moved out seven years ago. The same faces—you could spend the night pub-crawling just like the old times. That’s what the series of Krakow paintings is about.

Krakow/Warsaw, 2006

Krakow/Warsaw, 2006

Krakow is picturesque?

It’s picturesque like the artist’s retreat Kazimierz on the Vistula. A picturesqueness entirely not to my liking.

But you put Wawel Castle in those paintings.

Right, but I was being a little perverse. Because it’s not cool to paint things like that nowadays. Nobody in their right mind would paint such things. It’s hard to paint Wawel Castle when you’re a contemporary artist. It’s a bit like painting Hitler, it’s just out of line, unpalatable—

Pukeworthy.

Yes.

So let me ask you an unpalatable question. To what extent does Krakow live in the shadow of Auschwitz?

That shadow is evident in that there are excursions from Krakow to Auschwitz. But you don’t feel the war here, if that’s what you want to know.

Where do you feel the war?

In Warsaw, and in Nowa Huta because of its postwar nature.

What about villages?

Well, you always feel the war in villages. When you’ve seen Shoah , a lot of which takes place in the Polish countryside, it’s hard not to think about Polish villages as places affected by the war.

You see that when traveling through Poland.

What’s interesting is how few documentaries there are in which an outsider goes to Polish villages in the 1980s. In Claude Lanzmann’s film ( Shoah ), those villages are horrible. What’s also interesting is that all the survivors are shown in nice places like Basel, Tel Aviv and New York, while Polish peasants are shown standing in the mud in wintertime. So fucking depressing.

Untitled

, 2010

Untitled

, 2010

But that’s the impression you get if you go to towns outside of Łomża or Białystok—that those places never really recovered, that they had a culture which was exterminated, and that’s that. They’re in decline.

You don’t feel it that much here. It must have been strange for those people when something they had kept hidden for so long starts being exposed—I mean Gross’s book ( Neighbours: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (2001) by Jan Tomasz Gross).

When did you start wanting to go to Israel?

After watching Shoah , after Maus and finally after learning about Jedwabne. But, you know, what we can find in Israel depends on the extent to which we’re philo-Semitic, to what extent we’re interested in Jews from Poland. Going to Israel is looking for a bygone Poland. I had that when I saw photos of the Cinema Hotel on Zamenhof Street in Tel Aviv. It used to be the Wrzos movie theatre. And I think we’re interested in those Polish Jews. We’re looking for something that’s no longer here but might be found abroad. It’s like being in the States and going to a Polish neighborhood—everything there looks like 1980s Poland, everything is the way it was when its residents emigrated. It’s their image of Poland back then. And I reject that. But something that’s an echo of the past, like the Wrzos hotel—that was very pleasant.

In Tel Aviv I had the impression that Łódź might have looked that way if history had taken another course.

I never thought of it that way. It could have only happened on that coast. You see something different each time around. But you’re always looking for the past of the country you come from. At least that’s the way I see it.

While Auschwitz makes an impression on you.

It makes a horrible impression. It’s also because of the landscape—Birkenau is sinister, with its barracks and the perversely friendly landscape. In Auschwitz, you go between the blocks and know that it was a site of oppression.

Does that appeal to you?

It’s like you’re in a movie. You feel the proximity of evil, but you’re safe. And in Europe and Israel the war is like a quilt everybody can crawl under. Everybody has something to say on the subject.