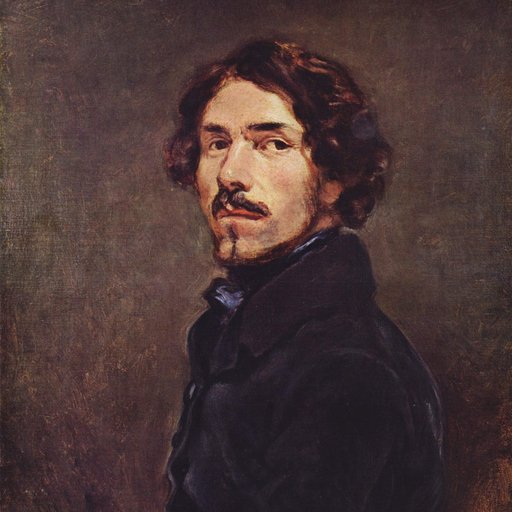

The German artist Isa Genzken is a sculptor whose creations revere, explore, and deconstruct both the great masters of art history and her own materials—no easy feat, but one that has earned her widespread critical attention in both the U.S. and Europe, culminating recently in her blockbuster 2014 survey at MoMA . Genzken, a former fashion model and the ex-wife of art-world demigod Gerhard Richter , is endlessly prolific in her efforts to create a true Gesamtkunstwerk—a "total art" that synthesis multiple forms of expression.

Her results are simultaneously contemporary and retrospective. Whether her far-reaching and interdisciplinary practice is shouting out to creepy Surrealist doll-maker Hans Bellmer or the Modernist sculptor Brancusi , Genzken is always infusing the zeitgeist of the post-apocalyptic now with the avant-garde visions of the past. Here, the artist discusses her extraordinary life's work in an illuminating interview with the German cultural critic Diedrich Diederichsen, excerpted from the Phaidon monograph Isa Genzken .

In a short video by the artist Kai Althoff in which the two of you are shown in conversation, he asks you why you have such an aversion to interviews. You explain that answering questions represents exactly the opposite of artistic work—of making decisions for oneself. It sounds as if, to you, creating art is like being on holiday, without any pressure, while making concrete statements in a conversation is like work. But people send postcards home even when they’re on holiday. Perhaps it would be possible to view an interview as a sort of postcard?

Actually you only think you’re not under any pressure when you make art because there’s nobody telling you what you’re supposed to do. But you have to find everything within yourself and make each decision on your own. And though there’s nobody forcing you to do anything, it can nevertheless turn into a disaster. In the creative process you’re very much on your own. You can’t simply call someone up and say, "Have a look at this."

And do you have imaginary conversations with other artists — people whom you know or don’t know? Do you ever ask yourself, "What would so and so think of that?"

No. I don’t do that sort of thing. My experience is that the artists I appreciate seldom approve of things made by other artists. I don’t often speak with other artists the way I do with Kai in the video, especially since we weren’t talking about my art, but rather something we created together—namely this short film. What was interesting was that we didn’t plan our conversation.

He asks you what you mean when you say that your work must be " modern ." You reply that it is precisely this aspect of interviews that you dislike: instead of being able to digress, the questions tie you down.

I gave him a completely unrelated answer.

I thought his question was very interesting. The word “modern” has, of course, two meanings. One pertains to things that are topical and contemporary, the other to the historical movement of modernism and modernity, which in a certain way is no longer contemporary. But I suppose that’s debatable. In any case, I have the feeling that your work is concerned with both. First, you incorporate contemporary symbols, products, objects, fetishes in your work, but you always make reference to the historical movement as well.

Yes, that’s true. But I don’t want anything to do with traditional elites and their self-awareness. That’s too rigid and boring. I focus on completely different sensibilities in my work. "Topical" is perhaps a better description than "modern." But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to be modern. My work is modern.

Fuck the Bauhaus

, 2000

Fuck the Bauhaus

, 2000

There’s certainly a sub-movement within historical modernism to which you make reference in a number of ways: the idea of the "social" work of art that both incorporates and influences its surroundings. This is something you’ve referred to often lately, even if in a critical fashion.

Fuck the Bauhaus

(2000) and

New Buildings for Berlin

(2001-2004) come to mind.

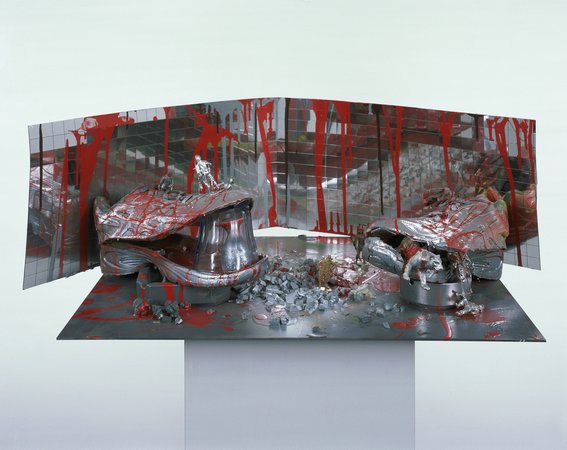

Yes, although in the last year and a half I’ve become more interested in a formal language of cheap materials and cheap production. I’m not talking about cheap, hand-made objects, like the self-modeled stuff that’s so amateurish you can see it a mile off. When I say "cheap materials" I mean industrially fabricated sculptures that are very interesting as sculptures in their own right. A year ago I started on the series Empire/Vampire, Who Kills Death (2002-2003) using small plastic objects, figures, toy tanks, and so forth. At the beginning, the topic of war was uppermost on my mind, because the conflict had just started up in Iraq. But then the objects I’d bought became much more important in themselves, and I started working with them more and more.

For example, that hippopotamus figure you see over there and the small iron next to it: I specifically bought things that were cheap, both in terms of how they were manufactured and their retail price. They were things I’d never be able to create with my own hands. If I were to model a hippopotamus it would never look like that—and I wouldn’t be capable of doing it anyway. It looks so good, not even

Stephan Balkenhol

could achieve it.

But I think I succeeded in creating something completely different. There’s no longer any mediocrity, but it’s important that it’s based on "everyday beauty." Nowadays there are more and more shops that sell these really cheap items. That’s where I found all of these figures and objects. I’m not only interested in what they portray, but rather in the formal aspect of how they were made. And they come from all over the world: one component is from Taiwan, the next from Mexico and the third from somewhere completely different.

As I said, I’m not speaking of poor quality. You find "poor" quality in

Markus Lüpertz

or Balkenhol and in many other areas of sculpture. I combined cheap things with expensive things—for example very expensive glasses, figures from film modeling workshops, or the costly reflective foil used in architecture. These are all mass-produced, assembly line materials, which I then altered with color or through their placement in unusual combinations.

A global taste of mass reproduction, yet characterized by exceptional formal qualities.

Yes, but I tried to place everything in a different artistic context. What appealed to me was that they could be movie scenes. The works should function as motion pictures rather than sculptures. You see a new picture from every different angle. Nothing is rigid or two-dimensional, but cinematic.

From the "Empire/Vampire" series

From the "Empire/Vampire" series

These cheap figures are also often described as emotionally moving. One sees an effort that’s futile—towards a totality of form and completeness that’s doomed to failure. It’s poignant somehow.

I disagree—that’s not well thought out. The work doesn’t fail in any way, and audiences react well—they’re perplexed. If you walk around my works and pay attention to the scenery, something different always emerges and you can always discover something new and sympathize with it. That’s the opposite of the tradition that began with the Black Square (Kazimir Malevich, 1915). This has been abused since the 1960s. Jackson Pollock , Barnett Newman , et cetera—I think they’re great. Conceptual art , too. That’s more where I fit in. But I didn’t want these modernistic, flung-down objects that strive to avoid all content.

Benjamin Buchloh criticized my ellipsoids for having too much content. He said to me, "You haven’t even understood Carl Andre yet." I said, "Of course I understand him. But I can hardly try to outdo Carl Andre." Of course, it was exactly this "content" that I wanted to bring back into the ellipsoids so that people would say, "It looks like a spear," or a toothpick, or a boat. This associative aspect was there from the very beginning and was also intentional, but from the viewpoint of Minimal art it was absolutely out of the question and simply not modern. And yet the ellipsoids made reference to modernism in terms of media and material.

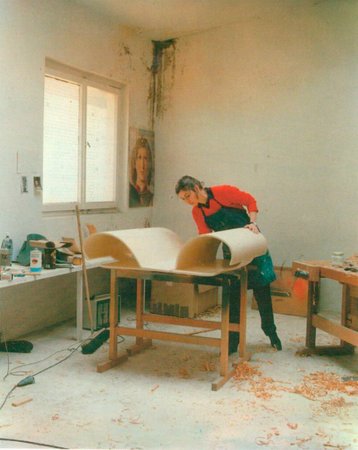

I had to go to the University of Cologne, where I knew a physicist who calculated and drew all of the diameters on the computer. After that I had to build it so that it would gain this horizon-like quality. I was influenced by

Bruce Nauman

. They were tremendously complicated to produce in terms of craftsmanship. I did it all by hand, but I wanted them to look—plop!—right out of the machine. People have always thought they were machine-made, but I wouldn’t have been able to afford to get them produced in an airplane plant or wherever you can have things like that made. I was also very proud of them because they helped me achieve a level of craftsmanship that many of my American colleagues no longer have.

With the exception of my outdoor sculptures I’ve always done everything by hand anyway. I don’t mean to insist that you have to do it that way, but it can’t hurt. The Modernists might see it differently.

László Moholy-Nagy

, for example, made pictures by calling up the factory and describing his images over the telephone. That was seen as especially advanced. And it was. But times change, and today everything is outsourced. And it’s also more interesting to develop things yourself. Many contemporary artists do it. My colleagues in my gallery share this inclination. Whatever "modern" means, I don’t reject the term. On the contrary, for me, "modern" means progress in social and aesthetic terms, but as a wanderer within diversity.

You said there was this moment at the beginning of your artistic development where you departed from Minimalism and connected it with “content” — does that also have something to do with the almost involuntary way that Minimalist objects can have "content," that they seem to look at you in an uncanny way? They have something like a psychotropic, psychedelic side, and can suddenly appear to have a soul — and this precisely because they aren’t supposed to have one. I was just thinking of how you’ve also given many of your objects proper names.

That way I always know exactly which is which. Over the years I’ve created many objects that, though diverse, look very similar. Because they carry the names of certain people I thought about during my work— Mies or Schindler , names of architects, or Schönberg —I can identify them precisely and know by heart how they look in detail. What else can you do? You could number your pictures like my ex-husband did, but he didn’t know by heart which picture went with which number.

Red Yellow Black Double Ellipsoid "Twin,"

1982

Red Yellow Black Double Ellipsoid "Twin,"

1982

Yes. But those are just series when you number them like that. When you assign names, then we’re not talking about objects in a series anymore, but rather about a specific type of logic, about something that must have been intended that way.

It’s always closely related to my feelings at the time. Back then I visited Lawrence Weiner , who had a boat in Amsterdam called Joma. I was invited to the boat and had such a nice evening that I used this name as the title for a work of 1981. And now I can always say exactly how that object looks. Later, I named the pillars after friends, but even then, I know exactly which pillar is Wolfgang [Tillmans] .

So the sculptures have a sort of physiognomy? They may belong to a genre, a series, but are they nevertheless individual beings that can be differentiated according to their unique physiognomies?

There have always been series, such as "30 Ellipsoids" (1976-82). I’d work on one thing until it became boring. Simply continuing the series would lead to certain ideas, which then provided the foundation for a new kind of work and a new series altogether. This would happen almost automatically. And that’s what some people don’t understand. People used to accuse me of being indecisive and not knowing what I want, because I was able to change so quickly from one genre to the next: "First she creates such elegant things and then goes on to make these strange plaster objects." Honestly, though, I think people have always given me credit for being able to move on. In my life, I’ve always been concerned with fluidity and opposed to rigidity. That’s been automatic—I’ve never had to think about it.

The artist in her studio in Düsseldorf, 1983

The artist in her studio in Düsseldorf, 1983

The elegant "Hyperbolos" and "Ellipsoids" were, of course, the things that put you in the spotlight. It’s clear that people wanted to associate you with "elegance." It was something new in the late 1970s. I feel that your subsequent works in plaster and cement were, in part, a deliberate attempt to thwart this association.

Absolutely. I really wanted a change—and to get away from the drudgery of the early works; they were incredibly difficult to make. So I went to a plaster workshop in Düsseldorf. I’d never been there before. When I arrived, I realized immediately: I really like this. It was something completely different from the places I’d been before, where we were working with wood. Then I played around a bit with the plaster and suddenly had the feeling, "Hey—this is easier than I thought!" I felt like a real sculptor [ laughs ]. Even so, making my way from plaster to cement was a longer road than I’d imagined.

And now your studio is located next to the city’s plaster moulding workshop.

I find that almost romantic. And there’s the Charlottenburg Palace next door and its lovely park. I’ve never been to the workshop, but I’ll go some time. I wouldn’t want to buy the Nefertiti they make there, but I’d gladly go and find out how a Nefertiti sculpture can be made really well.

Or they could make casts of your works.

Yes, but I’ve only made two bronzes in my life. I was at the best bronze foundry in Düsseldorf, and in the process the plaster moulds were ruined. That was terrible for me because I thought the plaster forms were much nicer. The bronze had lost something. I’d never do anything like that again. It would destroy the original. This being said, one thing I believe about my works so far is that I’ve been able to do justice to whatever material I’m working with. I’m able to make the best of it.

For my London exhibition “Wasserspeier and Angels” in 2004, I worked with this special sort of foil that’s very strong and stable. I rounded off the forms with it, and the light shined through. You can incorporate "inside" and “outside,” and everything appears so colorful and cheerful. But the decisive thing about working with the material was to create something round with it. That’s always the most difficult aspect of sculptures, and with this material you can do that.

How did you come up with the idea to create the sculptures you call "Wasserspeier" [gargoyles] for this London exhibition?

Whenever I’m in Cologne I go to the cathedral there several times a day because I find it absolutely magnificent inside. I’ve even referred to it before as my "atelier." Wolfgang Tillmans did a photo series there with me. And there’s the famous masonry shop there. It’s the workshop for the cathedral, a large area that you can look into from above, where they work on the stones. And that’s where I discovered the gargoyles, which are normally on the outside of the cathedral.

They were being restored. I saw their wide-open mouths, their terrible faces—they’re total figments of the imagination. They’re meant to protect the building: the rain water and filth flow from their mouths, away from the church, which is important for the upkeep of the building. I thought to myself that it would be good to take them to London. I tried to convince the cathedral’s master builder of the idea, but he wouldn’t have any of it. "Out of the question," he said. “They belong to the cathedral here in Cologne and nowhere else.” “But I just want to borrow them.” “No, that won’t be possible.”

I think they would have fit in well in London because there’s a certain architecturally similar “heaviness”—both in London itself, in the architecture of the city, and in the churches. For me, the gargoyles of Cologne were simply “English.” So I made these photos for the invitation card, which—as someone there told me—was “very British” in itself. And for the London exhibition I created my own gargoyles.

The "Wasserspeir"

The "Wasserspeir"

The "Wasserspeier" are also active sculpture—where the name itself ["water-spewers" in German] expresses an activity. The same applies to your works all the way back to the Weltempfänger ( World Receivers , 1987-92), where sculptures have a function, an activity. Yet at the same time, in that case, the activity is the act of receiving—so you have activity and passivity all in one. For me, that’s a very good description of the art of sculpture: held as if by magic in a concrete form, but always having something to do with the possibility of activity and passivity, which reveals itself in titles, contexts, etc.

Before the World Receivers I made the pieces about hi-fi systems ( Hi-Fi )—or rather, the sculptural aspect of hi-fi equipment—I photographed in 1979. Then, as usual, I built my own devices and called them "World Receivers"—even though you couldn’t hear anything. I found that aspect pleasantly absurd. They were made out of cement, but had small, real antennas. At the Frankfurter Kunstverein, Nikolaus Schaffhausen had recently put together an exhibition on Theodor Adorno. He displayed my World Receivers along with similar looking works by Bruce Nauman . Bruce had made casts of small cassette recorders. My antennas were also meant to be “feelers”—things you stretch out in order to feel something, like the sound of the world and its many tones. But, of all things, some people took offense at the feelers.

Too concrete, too literal?

Yes, but people were really disconcerted. And I was upset that they’d taken offense. But in the end they were pleased with my invention.

It’s no surprise that aficionados of "pure sculpture" thought you were making a joke about their artistic beliefs by using these very literal, “quoted” antennas in otherwise highly formalistic sculpture. On the other hand, and in contrast to other artists of the early 1980s, the works don’t only strike a humorous note. Their sober, “pure” aspects are no less important than the more literal, humorous “quotations.”

I didn’t even want to create such a contrast, or play one aspect off against the other.

There are many allegories of communication in your works, along with references to the outside world: windows, transmitters, receivers.

Yes. The idea is that you open yourself up and find different ways of looking at things, that you have more than one frame of reference for the sculpture. Take for example the sculpture I did in a public space in Munich (

Untitled

, a project for the award International Kunstpreis der Kulturstiftung der SSK München, 2004). It also has something to do with this notion of communication. It’s as big as possible, but still just as delicate as I could make it. And it takes up as little space as possible. (

El Lissitzky

was my hero when I was young.)

There’s an old cast-iron lantern, very tall, in the square in front of the Lenbachhaus. I attached a flower to it. Even though it looks very light, it’s very heavy—so heavy, in fact, that you’d normally have to anchor it to the ground. But instead of putting supports beneath it, like you would with a tent, I attached cables above the entire square in different directions and to the buildings on the other side: one to the Propyläen, one to the Lenbachhaus, and one to a more modern street light.

As a result, you get something that’s open and communicative. A structural engineer would have attached it firmly to the ground, but this way it’s held up securely but still draws in, and engages with, the entire square and the other buildings, and the cars can drive underneath it. Pedestrians can walk under it too.

As we’ve already discussed, your sculptures have this tendency to become characters, as if they had a soul. Over the course of several years, even decades, you seem to have developed an ensemble of characters. And at some point a story, a plot, began to emerge. But it wasn’t there from the beginning. When did you start to narrate?

I always have, but not to this extent. At some point—with the New York books ( I Love New York, Crazy City , 1996)—I started doing it more and more. I wanted to move to New York. In the beginning I didn’t have a studio and lived in a hotel, so I took pictures. I’ve often taken photographs when I don’t have a studio—for example, the Ohr ( Ear , 1980) photos, where I took pictures of women on the streets of New York. I didn’t have a studio then either. And at one point I put them together and pasted them into books. The idea was to make a guidebook for New York—not a normal one, but something for people who wanted to experience New York differently for a change: a lot crazier, more special, more multifaceted and beautiful.

Schauspieler (Actors)

Schauspieler (Actors)

An atmospheric guidebook? And how did you make the transition from the narration you get from turning the pages of a book to the sculptural narration you practice today? How did you make that step to the “cinematic” works?

I’d already made works in concrete that look like churches, ruins, and bombed-out buildings. These have a bit of this feeling to them. If you walk around them, you can discern different stories, find hard-to-reach nooks and crannies, areas that feel more secure. I was also quite explicitly playing with the idea of ruins and a Caspar David Friedrich kind of mood. So these works already had something narrative about them. I also placed small figures in them and, piece by piece, this just continued to develop.

When I was in New York I felt this compulsion to make a feature film. That’s where the title

Empire/Vampire, Who Kills Death

comes from: a screenplay I wrote at the time; but it was very difficult and I never published it. However, ever since then, the idea of narration has been a latent aspect of my work. I can make relatively small sculptures that go on to attain a large, relative monumentality. That’s a rare attribute. It never has a one-to-one effect, but rather the quality of a model. The true size is only realized in the viewer’s imagination.

Every narration has a punchline or an otherwise meaningful end. What is it in your story?

Humor, Cupid, love, and surprise are the future of modern art. How should I close? Many people are unhappy, and I think that sucks.